India and Myanmar have had several on-and-off cooperation partnerships against North-East (NE) insurgents operating from the territory of the latter. However, despite this cooperation, over 2000-3000 Naga, Manipuri, and Assamese militants continue to use Myanmar as a terror launchpad against India. Several observers have explained this phenomenon, by arguing that Myanmar lacks the intent and the ability to flush out these insurgents—a debate that needs serious reconsideration with growing India-Myanmar cooperation, and a deepening crisis in the latter.

A lack of intent?

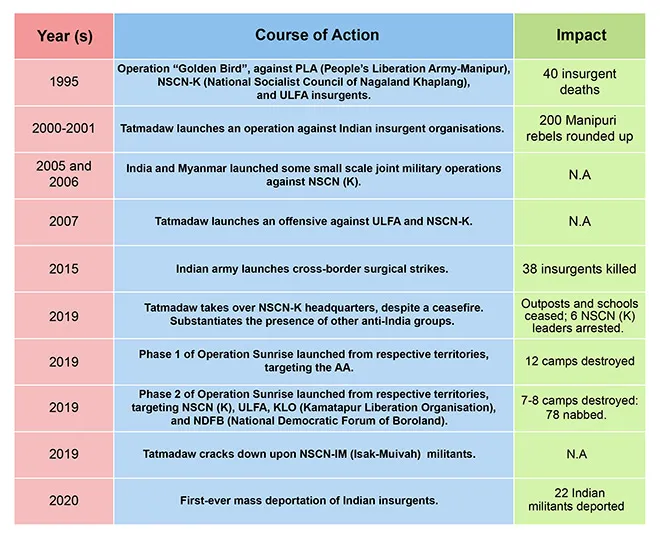

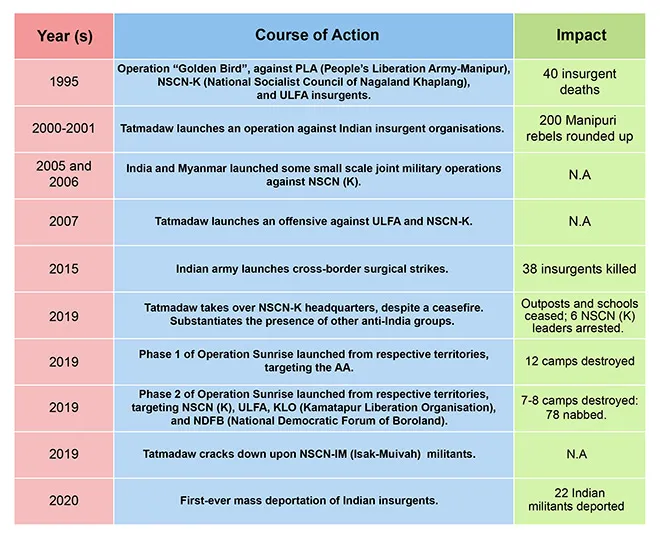

The roots of initial cooperation between India and Myanmar began in 1993. Intending to extend its influence in South-East Asia, and also deter Myanmar from harbouring the NE insurgents, India began accommodating the Tatmadaw (Myanmar military). On the other hand, to overcome its overdependence on China and appease India, the Tatmadaw started coordinating or acting against the NE insurgents (refer to Table 1 for details), with the help of Indian-supplied arms. This also created an unanticipated incentive for the Tatmadaw, to procrastinate their crackdown against Indian insurgents.

However, in recent years, the China factor has amplified India and Myanmar’s intentions to cooperate against the NE insurgencies. China continues to use the NE insurgencies to off-balance India, limit its growth, earn profits through black arms markets, and also widen mistrust between India and Myanmar. Consequently, China has even sheltered insurgent leader Paresh Baruah and is also supplying arms to his organisation, the United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA-I). Parallelly, China continues to engage and arm Myanmar’s ethnic rebels—Kachin Independence Army (KIA), Arakan Army (AA), and Ta-ang National Liberation Army—to keep the state closer and subordinated to China.

These insurgents of Myanmar and North East are further supplied with arms from China’s proxy—The United Wa State Army (UWSA). This supply of arms has empowered several insurgent organisations, including the AA, which now poses a threat to India’s Kaladan Project; which has the potentiality to transform the NE and Myanmar into a key geo-economic location. Consequently, both India and Myanmar have accelerated their cooperation against these insurgent organisations, in recent years.

Table 1. Authors own compilation of India-Myanmar cooperation against the NE insurgents, from various media and academic sources (more information is yet to be declassified or acknowledged).

Lack of capabilities?

Regardless of this increasing intention for cooperation, the Tatmadaw does face a capability crunch. The Tatmadaw is overstretched dealing with insurgencies elsewhere and is only temporarily and thinly present in the difficult borderland terrains of India, making it difficult to flush out the militants. Having realised this, India has been assisting Myanmar with intelligence, satellite images, and defence equipment. But, with no change in the Tatmadaw’s total armed forces personnel, the bordering regions of India continue to have a thin presence of the army. Therefore, despite various military operations, the insurgents continue to operate or re-establish in the bordering regions of India.

And since most of these insurgent groups are located in Indian borderlands, they have also developed close cooperation amongst them. Consequently, several Manipuri rebel organisations in Myanmar had formed a conglomerate called Coordination Committee, which later started working closely with another alliance of Indian insurgents in Myanmar, called the United National Liberation Front of Western South-East Asia (ULFWSA). This alliance includes several organisations such as ULFA, NSCN (K), NDFB etc, and were also responsible for the deadly 2015 ambush against Indian forces. Most of their bases were close to the NSCN (K) headquarters in Sagaing. The NSCN (K) governs some small Naga regions in Myanmar that are usually undisturbed by the Tatmadaw, following a deal with the government in 2012.

But, when the Tatmadaw conducted a series of offensives against the NE insurgents in 2019 including the NSCN (K), the majority of the insurgents moved to other bases that were beyond the Tatmadaw’s priorities and operational capabilities. Several Manipuri rebels moved to other camps and towns located in the South of Sagaing and Chin and Rakhine states, while ULFA-I and NDFB cadres relocated to the North and North East of Sagaing with the help of NSCN-K.

The coup and the future

Nonetheless, India’s intelligence and arms supply to Myanmar, along with the latter’s increasing intention, has led to an increase in security cooperation. This has forced several militants to surrender or return to India—contributing to India’s increasing securitisation. The surrender of 644 NE militants in the year 2020 alone, is a case in point for this. However, the ongoing civil strife in Myanmar has raised new opportunities for revival for the NE insurgencies.

Having suffered severe logistical and organisational damage from the Tatmadaw, several NE militant organisations are now looking for alternatives to survive and regroup. For long, the NSCN-K had sheltered the Indian groups in return for arms, and funds, which were usually obtained through smuggling and extortion. But the 2019 Tatmadaw offensives have indicated that the NSCN-K shelters are no longer safe, and these organisations would have to shift elsewhere– if they have to survive.

This comes at a time when the ethnic rebels of Myanmar are looking for revenues to recruit and support anti-coup protestors, while also funding their increased offensives to maximise power and deter Tatmadaw’s stepped-up offences. Out of these organisations, the KIA has adopted an intense offensive, while the AA has continued to criticise and also attack the army with its allies, despite a temporary ceasefire.

And these organisations have had a long history of training, cooperating, accommodating, and selling arms to Indian insurgents. The KIA has had historical relations of training and sheltering several Manipuri and ULFA rebels. Similarly, the AA has been cooperating with Manipuri organisations of UNLF and PREPAK by allowing them to establish camps in Rakhine and Chin states, in return for some logistical support. And, the KIA, Chin organisations, and UWSA of Myanmar are also acting as middle-men and arms suppliers for several NE insurgents.

With prevalent cooperation as such, these organisations might soon start supplementing each other’s needs. The NE insurgents might be able to generate revenue for Myanmar organisations, by providing them with funds, extortion money and new arms and drug trafficking routes, in return for being sheltered and letting them carry out operations against India. Thus, intensifying the violence and leaving the Tatmadaw and its material capabilities more preoccupied with the Myanmar insurgents.

In addition, the displacement crisis from Myanmar has pressurised India to choose between domestic demands and the Tatmadaw, which expects India to reciprocate its security cooperation by handing over the fleeing police personnel and civilians from Myanmar. Supplementing it, there is also a high probability that sanctions against the military’s revenue and businesses will push the Tatmadaw to revert to exploitation and corruption. This also includes tactics of local and low-level officials collecting a fee for not disturbing the Indian insurgents and their activities within Myanmar. Thus, such instances might contribute towards the reappearance of the questions regarding each other’s intentions on security cooperation.

It is, therefore, an urgent need for both the countries to disentangle the brewing crisis before it generates severe consequences for the region and India’s NE in specific.

Aditya Gowdara Shivamurthy is a research intern at the ORF. He is a MSc International Relations graduate from the London School of Economics and Political Science.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV