The fact that the very existence of a wing of a nation’s armed forces may act as the sine non qua for peace, may seem counterintuitive to most observers. Yet it is a view that has endured in key circles of strategic thought over decades. “A good navy is not a provocation to war. It is the surest guarantee of peace” declared US President Theodore Roosevelt in 1902. Separated by just over a century, strategic theorist John Mearsheimer would reiterate this view in his 2004 magnum opus The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. “Large bodies of water are formidable obstacles that cause significant power projection problems”, Mearsheimer explains, expounding on his principle of the “stopping power of water”—the idea that oceans provide natural barriers to interstate conflict.

“A good navy is not a provocation to war. It is the surest guarantee of peace” declared US President Theodore Roosevelt in 1902.

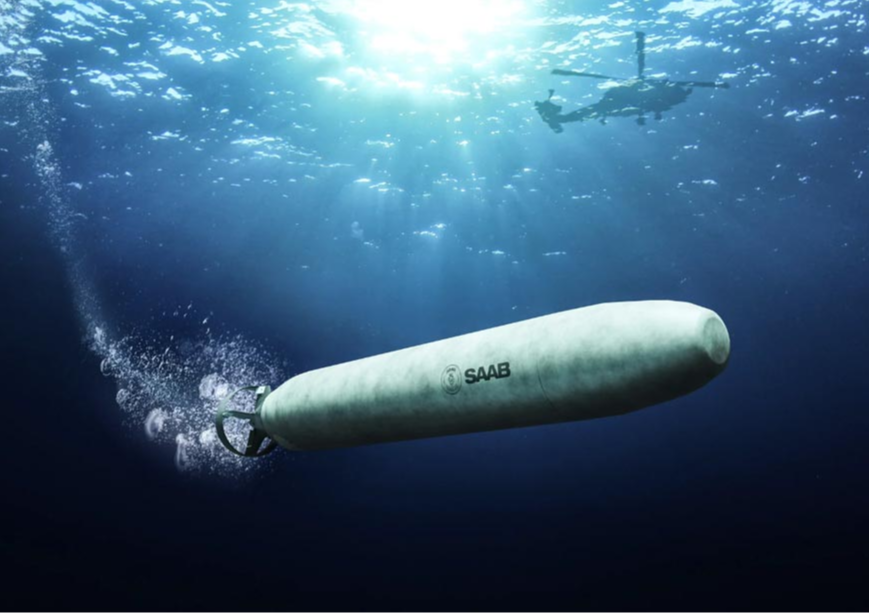

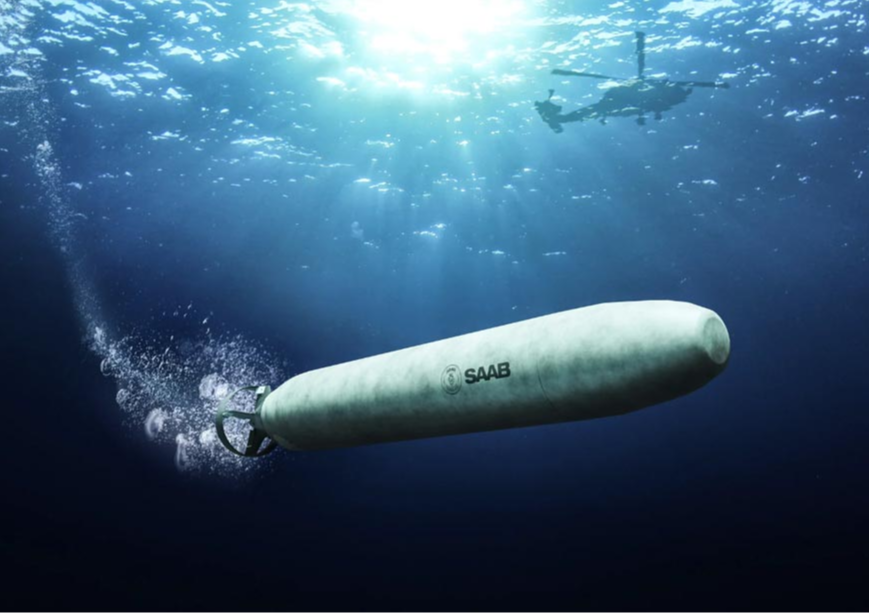

While full-scale naval warfare remains in the realm of speculation in a multipolar world, covert action at sea, particularly with the advent of unmanned undersea vessels (UUVs) as a tool of submarine warfare, is a reality which has increasingly come to challenge accepted logic about oceans as impediments to conflict. Given their utility as a means of achieving kinetic effect against adversaries while maintaining plausible deniability for authorising states, what then might the growing ubiquity of UUVs as a means of subterfuge mean for the future of covert action?

UUVs and covert action: A brief history

Like several other military technologies in common use today, the technological development of UUVs began in the early years of the Cold War. The first UUVs were developed by the United States Department of Navy’s Office of Naval Research in the 1950s, being used in a military context only in 2003, when they were used by coalition forces to clear the Iraqi port of Umm Qasr of seabed mines. Since then, governments worldwide have recognised their utility as a means of submarine warfare and intelligence-gathering, but also as a tool for conducting covert action, which, based upon the US National Security Council’s framing, may be defined as “operations so planned and executed that any responsibility for them is not evident to unauthorised persons and if uncovered the authorising government can plausibly disclaim any responsibility for them”.

The first UUVs were developed by the United States Department of Navy’s Office of Naval Research in the 1950s, being used in a military context only in 2003, when they were used by coalition forces to clear the Iraqi port of Umm Qasr of seabed mines.

Unlike clandestine operations (which it is often conflated with), the kinetic effect of covert action is not meant to be completely hidden, with its performativity aiming to achieve both tangible strategic effects while also serving as a form of political theatre. In this respect, UUVs provide states with many advantages. Not only can they be easily discarded into the seabed—a domain which still remains mostly unexplored—when facing interception, but the kinetic effect that UUVs may deliver to adversary infrastructure serves as a signal of intent, providing visibility, and therefore strategic effect, in international politics.

The threat to CNI

Illustrative of the increasingly interconnected world order that has come to bear influence on national iterations of statecraft, the proliferation of undersea critical (national) infrastructure (CNIs) networks also provides a new domain for interstate competition. The growth of UUVs for military purposes has coincided with the expansion of undersea CNI, the latter providing a new domain for interstate competition, which may manifest through covert actions and subterfuge. Instances such as the September 2022 detonation along the Nordstream pipeline that partially disrupted supplies of Russian natural gas to European states, or Russia’s severing of fibre-optic cables connecting the Svalbard archipelago in the Arctic to the Norwegian mainland in January 2022, were both conducted using UUVs. Precedents such as these highlight the usefulness of UUVs in disrupting adversary states’ undersea infrastructures and supply chains of strategic resources—energy or data—as a means of gaining leverage. In each of these cases, the impact of the disruption was dramatic and signalled political intent, while also broadly concealing the involvement of the states responsible, as covert action seeks to do.

The growth of UUVs for military purposes has coincided with the expansion of undersea CNI, the latter providing a new domain for interstate competition, which may manifest through covert actions and subterfuge.

Like their airborne counterparts, the relative cheapness of UUVs also makes them an attractive tool for violent non-state actors, who may seek to leverage their asymmetric capabilities to attempt to coerce adversary states. The sabotage of three key fibre-optic cables in the Red Sea in March 2024, said to be connecting Europe with Asia and Africa, was claimed to have been the work of the Houthis, an Iranian proxy militant organisation in Yemen. While the Houthis continue to disclaim responsibility, the group’s past use of undersea ‘suicide drones’—the cheapest of which are estimated at prices as low as US$2,000—serves to demonstrate the outsized role that such devices can play in helping non-state actors exercise outsized influence in international politics while destroying evidence of their involvement. It ultimately highlights not just the utility that UUVs provide in terms of plausible deniability, but also their low costs facilitating kinetic covert operations.

Future implications

Reflective of the resurgent pre-eminence of the maritime domain within the interstate strategic competition, the emergence of UUVs for covert action against adversaries raises new policy implications for decision-makers.

Given their utility for covert action, it is forecasted that governments will invest in acquiring greater stealth capabilities for UUVs, including technologies allowing greater deep-sea exploration. The interception of UUVs can result in disclosures about the deploying state’s wider strategic intent, causing international embarrassment for the deploying state, as was observed in January 2021 when Indonesian authorities released hydrographic information digitally stored in a Chinese UUV intercepted in the South China Sea as proof of China’s violation of international maritime law. While stealth technologies have long been integral to UUV engineering, as illustrated by Russia’s ‘Poseidon’ vessels—governments are likely to invest more in new forms of stealth technology to avoid interception by increasingly sophisticated undersea surveillance systems.

Private arms dealers, criminal enterprises, and governments may all seek to dominate this market- leading to increased competition and eventually even lower selling costs, facilitating the proliferation of UUVs.

The low costs and focus on ensuring greater plausible deniability will also most likely result in an expanded market for one-time use undersea ‘suicide’ drones. Beyond their affordability, such UUVs also self-destruct on impact, in the process destroying any evidence of state culpability. While they may continue to signal strategic intent through kinetic effect, acquiring physical evidence for UUV attacks on undersea CNI is likely to become more difficult. While Ukrainian forces have already been known to use such devices in their war with Russia, so have non-state actors like the Houthis, attacking Israeli energy infrastructure in 2021 and fibre-optic cables three years later- providing a glimpse into a small but rapidly growing untapped defence market. Private arms dealers, criminal enterprises, and governments may all seek to dominate this market- leading to increased competition and eventually even lower selling costs, facilitating the proliferation of UUVs.

Defined by the twin principles of plausible deniability and the delivery of tangible strategic effect against adversaries, covert action is today an increasingly attractive option for policymakers in a multipolar and interconnected world who seek to gain leverage over competitors while simultaneously avoiding the costs that come with other escalatory measures. At a time when the maritime domain increasingly serves as the nucleus for interstate strategic competition, covert action must increasingly adapt to the distinct conditions of this theatre. The ubiquity of UUVs is therefore emblematic of the direction that covert operations may take in an increasingly interconnected yet multipolar world—one where deniability intersects with strategic leverage and interdependence with the low costs of undersea subterfuge.

Archishman Goswami is a postgraduate student studying the MPhil International Relations programme at the University of Oxford.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV