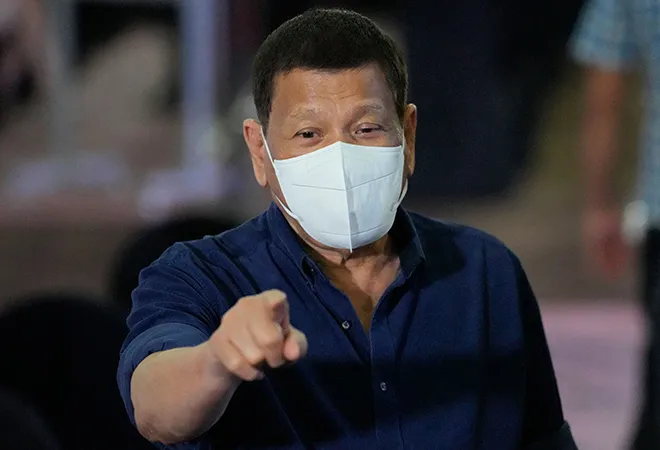

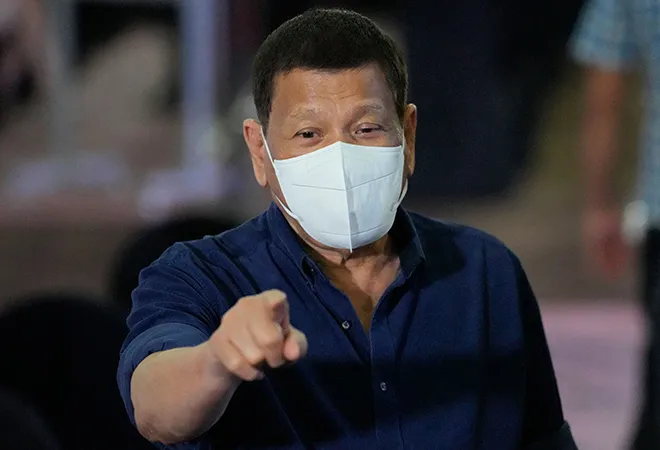

When the Philippine President, Rodrigo Duterte, announced his retirement from politics recently, not everyone believed him. After all, he said the same thing in 2015 when he was the Mayor of Davao City—only to make a complete turnabout and run for president.

Under Philippine laws, Duterte cannot seek a second term. But he can vie for the post of Vice-President in the May 2022 elections as he had earlier declared, or run for mayor should his daughter, Sara, the incumbent mayor of Davao City, decide to join the presidential contest. The final roster of candidates will be known by mid-November, the deadline for filing of candidacy. Politics in the Philippines—highly personalistic and with fluid party lines—can be full of surprises.

The stakes are high, from the future of democracy in a country that used to enjoy the reputation of being the freest in Southeast Asia to its place in geopolitics as Duterte’s pivot to China eroded the Philippine victory in its maritime dispute with China. Under a new leader, will there be a shift in policies? Two questions are key: Will the next president continue Duterte’s autocratic rule and his embrace of China? Or will they stop the democracy hemorrhage and assert its sovereign rights over the West Philippine Sea?

Six candidates are jostling for the presidency, a crowded race in a chaotic multi-party system. Two of them—Senator Ronald dela Rosa and Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., son of the late dictator—will most likely continue President Duterte’s policies. After the Philippines won its maritime case against China in an international tribunal in 2016, Duterte has set it aside, saying that the country needs investments, aid, and trade from China. He has even disparaged the arbitral ruling which declared China’s nine-dash line claim over most of the South China Sea illegal, calling it a “piece of paper to throw to the waste basket.”

Marcos has echoed Duterte’s views. He said “the policy of engagement that the Duterte government is doing, although it is criticised, is the right way to go.” Dela Rosa, a former Police Chief who implemented the brutal war on drugs, killing thousands, is a loyal ally of Duterte.

The four other candidates—opposition leader Vice President Leni Robredo, Senator Panfilo Lacson, Manila Mayor Francisco Moreno, and Senator Manny Pacquiao—have publicly disagreed with Duterte’s China policy. Robredo has been the most vocal in criticising Duterte’s violent drug war and defeatist position on China.

Embrace of China

Duterte is the first Philippine president to side with China and pull away from the US. This stems from his dislike of the US as a former coloniser of the Philippines and US criticism of his war on drugs. His foreign policy is also an extension of his friendships with Chinese businessmen in Davao when he was mayor.

“Duterte of the Philippines is veering towards China because China has the character of an Oriental. It does not go around insulting people,” Duterte said in a speech. It was early in his term when he announced his “separation” from the US, both militarily and economically, in a state visit to Beijing in 2016.

He also tapped a Chinese businessman as his economic adviser for a year to help bring investments to the country. In doing so, he violated Philippine law which bans foreigners from holding government posts.

But Duterte’s embrace of China has not yielded the expected economic benefits. China had pledged US $24 billion in investments and loans but only a fraction, about 5 percent, has come to fruition. When it comes to aid, Japan remains the largest source of foreign aid. China comes in only as the sixth biggest provider of foreign aid.

Duterte’s embrace of China has not yielded the expected economic benefits. China had pledged US $24 billion in investments and loans but only a fraction, about 5 percent, has come to fruition. When it comes to aid, Japan remains the largest source of foreign aid. China comes in only as the sixth biggest provider of foreign aid.

Still, Duterte’s preference for China never waned. It was in full display when the pandemic struck as his choice of vaccine was Sinopharm from China. He got his jab even before the vaccine was approved for emergency use in the Philippines. His guards, members of the Presidential Security Group, were amongst the first to be vaccinated in the country with smuggled Chinese vaccines, ahead of medical front liners.

Filipinos and the US

There seems to be a disconnect between public opinion and Duterte’s China policy. Surveys have consistently showed a low regard for China. In a July 2020 survey by the Social Weather Stations, a leading polling outfit, Filipinos trusted China the least and the US the most.

On the West Philippine Sea issue, a survey in July 2021 showed that 68 percent of adult Filipinos favour alliances with other countries to defend Philippine sovereign rights in the contentious waters, while 47 percent said the government is not doing enough to assert the country’s rights in the area.

Even with vaccines, Filipinos prefer US as a source of COVID jabs, although China has provided most of the vaccines in the country. Both China and the US engaged in vaccine diplomacy but the US has given far more doses.

Duterte phenomenon

Despite all this, Duterte has remained popular, with a 75 percent satisfaction rating as of June this year. This is unusual in the Philippines where presidents’ popularity ratings dip in their last year or so in office, contributing to his or her lame duck status. But, as it has turned out, many support the drug war, showing frustration with the justice system and a preference for a strong hand, a leader who is seen as decisive.

During the pandemic, Duterte ordered the government to give money to the poor and those who have lost their jobs. This partly explained the earlier approval rating (65 percent) for his pandemic response—although this has since declined (59 percent).

During the pandemic, Duterte ordered the government to give money to the poor and those who have lost their jobs. This partly explained the earlier approval rating (65 percent) for his pandemic response—although this has since declined (59 percent).

There’s the personality factor, too. Many like his brash jokes and informal style of talking and dealing with people, showing a common touch. One hallmark of his leadership is that he projects himself as a man of action. He likes to frequently visit military camps, disaster sites, and wakes. When he was mayor, he used to patrol Davao’s streets on a motorbike.

Duterte rose to the presidency in 2016, riding on a wave of authoritarian populism that engulfed not only the Philippines but other countries like Brazil (Bolsonaro), Hungary (Orban), the US (Trump) and Turkey (Erdogan). He promised to stop the descent of the Philippines into a narco-state and engaged in a scare campaign that exaggerated criminality and the drug problem.

But, in his last months in office, Duterte’s luck is running out. He is facing a big-time corruption scandal that is tied to China. The government favored a newly formed company with links to his past Chinese economic adviser over other suppliers with track records. It bought about 11 billion pesos (US $220 million) worth of face masks, personal protective equipment and other pandemic supplies in what government auditors found to be questionable contracts.

Duterte’s pro-China policy is expected to be a campaign issue in the lead up to the presidential election in 2022 but with a new twist: Corruption. While it’s very early to say how things will play out, key questions on the return of democracy and assertion of sovereign rights in the West Philippine Sea remain.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV