It’s already been one year since the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the outbreak of COVID-19 as a global pandemic, and only eleven years after the last pandemic — the H1N1 Swine Flu. The novelty, transmissibility, and high infection rate of the virus has made it elusive and has rendered nations powerless in handling it. The African continent, however, has been an outlier with respect to the relatively low mortality and infection rates compared to other continents. This is mostly attributed to the early proactive response employed by African countries, and their prior experience in dealing with disease outbreaks like Ebola, Tuberculosis, Cholera and Malaria.

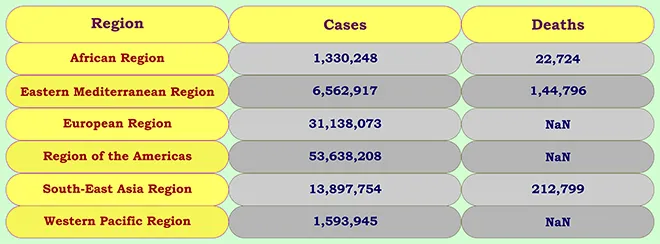

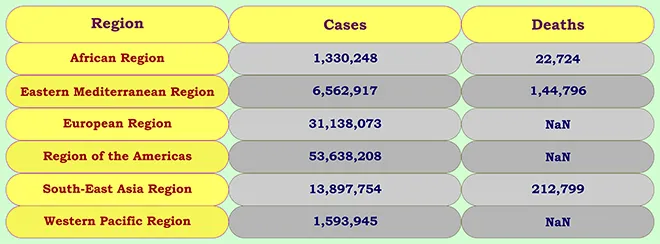

Number of total cases and deaths by region

Source: Observer Research Foundation, COVID-19 Tracker, accessed on 17 March 2021.

Source: Observer Research Foundation, COVID-19 Tracker, accessed on 17 March 2021.

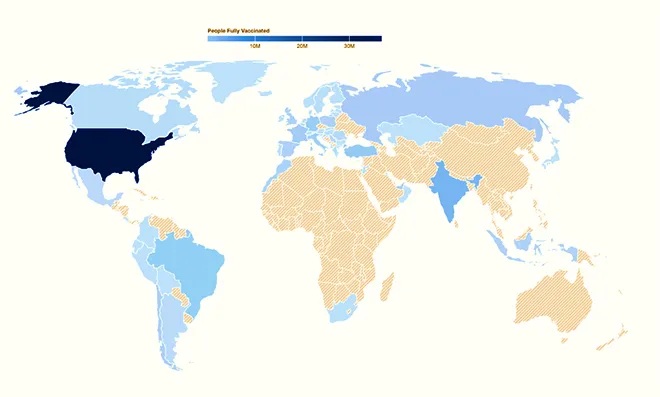

Another area in which the African continent is an outlier, not shockingly but regrettably, is in vaccine access. African nations have consistently lagged behind in the global race to procure vaccines for their vulnerable populations. With comparatively less economic and political bargaining power, and myriad logistical and capacity challenges, the second most populous continent in the world lies at the mercy of the ‘benevolent’ West and, more recently, the East too, in the hopes of being supplied with vaccines. At the time of writing this report, barely 260,000 persons on the African continent have been vaccinated whilst in the United Kingdom alone — a country with about 66.8 million people — about 400,000 people have been vaccinated. This staggering statistic raises significant questions about vaccine access, equity, and global inequalities which disproportionately affect the African continent in various ways.

African nations have consistently lagged behind in the global race to procure vaccines for their vulnerable populations.

Vaccine nationalism

The question of vaccine equity is one that has featured prominently in international COVID-related discussions prompted by the fear of vaccine nationalism — a situation where more powerful countries disproportionately prioritise their vaccine needs over other less powerful countries. According to the World Economic Forum, the world’s wealthiest nations have ordered stock piles of vaccines “enough to protect their populations several times over” — a direct contradiction to the egalitarian global rhetoric that has been used when discussing vaccine access.

At first glance, the nationalistic, “country first” sentiment might seem legitimate, but there are real dangers and concerns raised by vaccine nationalism. Even though Western countries rush for the vaccines in the hopes of vaccinating and thus protecting their population, the remaining unvaccinated populations of the world are still susceptible to the virus which might engender possible mutations. These mutations can be potentially more aggressive, more transmissible, and even evade previous immunity, thus leaving vaccinated populations at risk. Dr. John Nkengasong, Director of the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, therefore, asserts that “it has to be very clear that no part of the world will be safe until all parts of the world are safe.”

At first glance, the nationalistic, “country first” sentiment might seem legitimate, but there are real dangers and concerns raised by vaccine nationalism.

The point is clear: Without a concerted effort at vaccinating as many people as possible globally, COVID-19 remains a real and existing threat to the world.

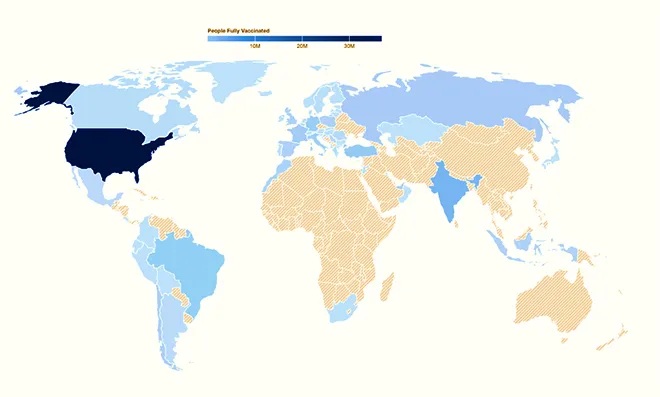

Number of vaccinated individuals by continent

Source: Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Centre

Source: Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Centre

Apart from the fact that vaccine nationalism is counterproductive because it encourages the existence, transmission, and mutation of this deadly virus, which has already claimed about 2.6 million lives, it also the leads to unnecessary economic competition. This competition could lead to a spike in prices, bringing the cost of the pandemic to about US$ 1.2 trillion a year, opined Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director General of the WHO.

Whilst it is important to acknowledge the efforts being made to provide low-income countries with vaccines through the COVAX program, the numbers speak of a foundational inequality in healthcare access in Africa. A case in point is Nigeria — a country with a population of approximately 201 million has received a meagre 4 million vaccines whilst a country like Canada with a population of merely 37 million has received over 3 million doses and expects to receive almost 1 million more in the coming days.

The point is clear: Without a concerted effort at vaccinating as many people as possible globally, COVID-19 remains a real and existing threat to the world.

Critics may contend that the overall younger population on the continent buys some time for vaccine distribution and administration as the effects of COVID on younger populations are generally less severe. However, this logic fails to take into account the danger of asymptomatic patients and their potential role as vectors transmitting their undetectable viral load to the most vulnerable populations.

What are Africa’s options?

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the huge disparities that exist in healthcare and vaccine access between Africa and the rest of the world. Most African countries are yet to start inoculating their citizens and a slow vaccine rollout risks further delaying the economic recovery, as African economies contracted for the first time in 25 years following the outbreak of the pandemic. It is increasingly evident that Africa will find it difficult to obtain the requisite vaccine supplies from Western nations to combat the pandemic. Despite having limited options, African countries have started to look beyond the West, with policymakers across the continent seeking jabs from Russia, China, and India.

It is increasingly evident that Africa will find it difficult to obtain the requisite vaccine supplies from Western nations to combat the pandemic.

African countries are primarily pinning their hopes on the WHO-backed COVAX (COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access) facility — an initiative that aims to ensure fair and equitable access to vaccines in developing countries. The facility aims to vaccinate twenty percent of the most vulnerable population of each participating country, regardless of income levels by the end of this year. However, concerns over gaps in funding and the continent’s immunisation needs have African countries looking at alternative ways of securing vaccine doses.

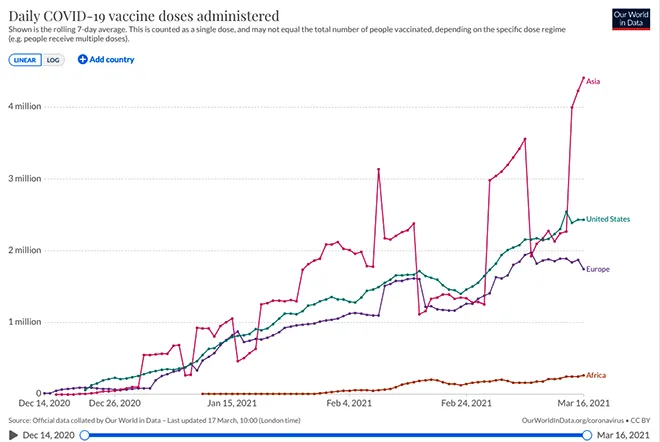

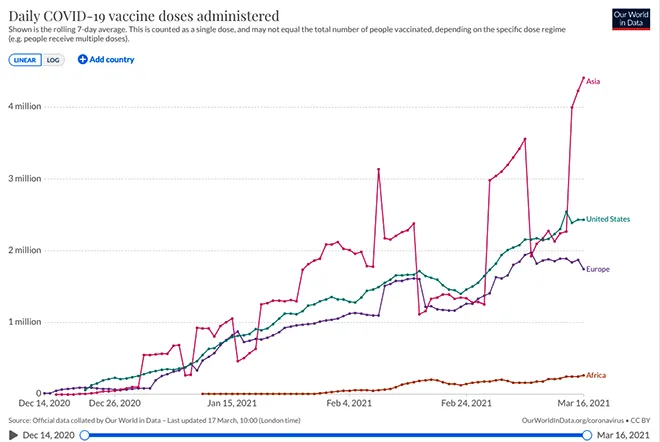

Source: Our World In Data

Source: Our World In Data

Currently, the African Union has reserved 670 million vaccine doses for the continent, which includes a combination of the Pfizer, Oxford-AstraZeneca, and Johnson & Johnson vaccines. Some African countries are also entering into bilateral deals with firms, while others are playing the diplomatic card and turning to China and Russia in the hopes of obtaining the Sinovac/Sinopharm and Stupnik-V, respectively. However, vaccine donations from Beijing and Moscow have so far been small, costly, and cryptic — with key data clouded in obscurity. In addition to the fact that neither the Russian nor Chinese vaccine have been approved by WHO for emergency use yet, transparency issues serve as a major discouragement to Africa’s procurement of these vaccines.

Vaccine donations from Beijing and Moscow have so far been small, costly, and cryptic — with key data clouded in obscurity.

India has also been quick to realise an opportunity to reinforce its own image as the ‘pharmacy of the world’ and has supplied COVID-19 vaccine doses to several African countries. This effort has been driven by the Serum Institute of India — manufacturer of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine. Currently, India has already sent vaccines to 12 African countries on grant basis (Mauritius, Mozambique and Kenya have received the highest number), eight African countries on commercial basis (Morocco has ordered the highest), and 23 African countries through the COVAX facility (Nigeria, Ethiopia and the Democratic Republic of Congo have received the highest).

Africa’s vaccine procurement challenges

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to grow heterogeneously in Africa as more African countries record the second wave of coronavirus infections, and nations like South Africa have begun to record more novel and infectious variants. Currently, only three African countries have plans to manufacture international COVID-19 vaccines: Morocco (Sinovac, China), Egypt (Sputnik-V, Russia), and South Africa (Johnson & Johnson, USA). Several of the vaccines like the ones developed by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna require ultracold storage, which makes it difficult to store and distribute in several parts of Africa that have considerable logistical, transport, and infrastructural challenges. Access to vulnerable communities like minorities, refugees, and internally displaced persons in conflict-affected regions is also severely restricted.

Another challenge is the significant fiscal constraints on African governments that has rendered vaccine coverage across Africa off to a slow start. Only Mauritius, Seychelles, Egypt, Morocco, Guinea, and Rwanda had begun rolling out their vaccination programmes by February 2021. South Africa’s programme was initially halted due to concerns around the AstraZeneca vaccine’s efficacy against the 501Y.V2 variant of the virus, but has now rolled out the US’s Johnson & Johnson shots.

African governments need to conduct regular vaccine awareness campaigns and engage at the community and grassroot levels.

Additionally, another challenge is misinformation and vaccine hesitancy. African scientists and experts have expressed their worry about growing levels of resistance and misinformation around testing and vaccination on the continent. To combat this menace, African governments need to conduct regular vaccine awareness campaigns and engage at the community and grassroot levels. Unless this issue is proactively and comprehensively addressed, the efforts to distribute vaccines, achieve herd immunity, and end the pandemic, might unfortunately be insufficient on the African continent.

The race to secure COVID-19 vaccines has laid bare the inherent inequalities in access to global healthcare, which adversely affects developing populations like those in the African continent. Might this realisation be the catalyst that drives Africa out of the dependency paradigm to more sustainable, long-term, development solutions? Only time will tell.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source:

Source:  Source:

Source:  Source:

Source:  PREV

PREV