As the humanitarian catastrophe exacerbates in Afghanistan, the Taliban and the international community have intensified their engagement with each other. While the former has begun to use these interactions to seek international legitimacy and aid, the latter perceives this as an obligation.

Subsequently, the UN is raising US$ 4.4 billion—the largest appeal for any single country; the US will be releasing US$ 3.5 billion , and the EU has promised over US $570 million. The World Bank also unfroze US $280 million, and the Organisation of Islamic Countries and the Gulf Cooperation Council have assured to mobilise resources and help Afghanistan. Their priority, as of now, is to mitigate the humanitarian disaster, assist through a parallel administration, and deny the Taliban from accessing these resources.

However, these humanitarian efforts are half-hearted and lack the political will. What Afghanistan needs at the moment is an economic solution and long-term engagement. But these solutions seem intangible as it has high political costs for all the concerned parties.

Leveraging the crisis

Primarily, the international community is hesitant to promote an economic solution for Afghanistan that is under the helm of an unreformed Taliban. There is a belief that this assistance could strengthen the Taliban’s wealth, legitimacy and control over the Afghan state and increase the number of transnational challenges.

Afghanistan, humanitarian, Taliban, UN, EU, World Bank, US, economic, wealth, legitimacy, human rights, Women, terrorist, ISKP, education, employment, Russia, Ukraine.

The international community has thus demanded the organisation to uphold women and human rights, ensure equality and protect all Afghans, form an inclusive government, grant amnesty for individuals, limit transnational crime, and not harbour any terrorist groups in Afghanistan.

However, these demands have high political costs for the Taliban. The organisation continues to be divided on human rights, women's education, employment, and interactions and linkages with other terrorist organisations. An internal rift or an ideological clash within the organisation remains the least preferable option, especially when ISKP is emerging as a new alternative. Similarly, the organisation's insurgency mobilisation tactics will likely complicate any such reforms, further enhancing the costs. Nonetheless, the Taliban have continued to make empty promises of reform, hoping to seek international legitimacy and aid.

A half-hearted response

For most of the regional powers neighbouring Afghanistan, the humanitarian crisis also sets in a dilemma. These countries are keen on humanitarian aid to avoid migration, economic chaos, and regional instability. Evidently, regional powers such as Iran, Pakistan, Russia, Uzbekistan, and China have continued to ask the West to unfreeze Afghanistan’s frozen assets and deliver more humanitarian aid. But neither of these states have shown interest in a long-term engagement with the new regime too. There is a trust deficit for the Taliban, as they anticipate that a strong unreformed Taliban sitting next door would intensify their terrorism, trafficking, and extremist challenges. A half-hearted humanitarian response is their best go-to option for now.

There is a trust deficit for the Taliban, as they anticipate that a strong unreformed Taliban sitting next door would intensify their terrorism, trafficking, and extremist challenges.

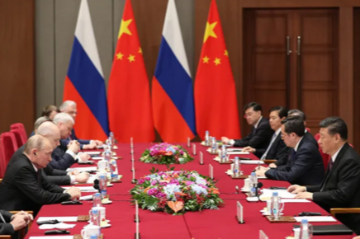

Consequently, China—the richest of Afghanistan’s neighbours—has offered only US $31 million in humanitarian aid, despite appealing to the US to withdraw its sanctions and showing interest in investing in Afghanistan. Similarly, Iran, Pakistan, Russia, and Tajikistan have continued double-dealing and engaging with other key non-Taliban players. They are hoping this could mitigate their apprehensions by pressurising the Taliban, creating some leverage against the organisation and compelling them to reform.

Challenges to the western world order

Similarly, for the West to recognise or strengthen the Taliban regime would come as a vital blow to its value-based order that is already under strain with their chaotic withdrawal, China’s assertiveness, and Russia’s recent activities in Ukraine. There is also a lack of interest in the West to re-invest in Afghanistan; there is also a possibility that any re-engagement would invoke criticism from their domestic polity and electorates. The West is, thus, opting for a hands-off approach in Afghanistan, which also explains their limited interactions with other non-Taliban players.

On the other hand, leaving the humanitarian catastrophe unattended would lead to a collapse of the Afghan state. It would intensify the West’s migration, trafficking, and terror challenges. In addition, its inability to help poor Afghans despite possessing the material wealth, having promised development aid and having contributed to their state-building will raise questions of the West’s commitments and values for its allies and partners.

The West is thus in a dilemma of neither wanting to strengthen the current Taliban regime nor wanting the Afghan state to collapse—both of which would highlight its failures. Its only bet, for now, is to provide more humanitarian assistance and compel the organisation to reform.

Its inability to help poor Afghans despite possessing the material wealth, having promised development aid and having contributed to their state-building will raise questions of the West’s commitments and values for its allies and partners.

The stalemate

The diverging positions and political costs of all the players have thus limited them from achieving a sustainable solution in Afghanistan. The Taliban continue to stay reluctant to reforms and are leveraging the crisis to seek legitimacy and aid by providing false hopes and promises. On the other hand, the neighbouring and Western powers are hoping for a reformed Taliban, despite differing on how to (or not to) engage with the new regime. A sustainable solution beyond humanitarian assistance would thus likely be difficult unless there is a change in a state’s security calculations, or the Taliban initiates limited reforms to accommodate the interests of one or some states.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV