Intra-Afghan talks finally took off in Doha on 12 September, almost six months after they were originally scheduled for. Facilitated and supervised by the United States, representatives of the Ghani government and the Taliban began the historic peace negotiations, aimed at ending the decades-old war, forging a political settlement.

The opening ceremony of the talks witnessed the participation of key regional and international stakeholders as well, with each participant sharing their respective expectations from the process, and reiterating their commitment to bringing enduring peace in Afghanistan. Though the start of the direct talks between the Taliban and Afghan government negotiators is a significant development in itself, the road ahead will likely be marred with a number of challenges.

Conflicting visions

Though the Afghan government and the Taliban have expressed willingness to engage with one another in all sincerity, actual negotiations have not yet taken place, owing to disagreement on the primary means of dispute settlement. Soon after the inauguration, contact groups were set up on both sides, to work out the terms and conditions that negotiations would have to abide by, as well as to prepare the final agenda for talks.

Even as the reported development indicates a compromise by Afghan negotiators to overcome an obstacle to direct negotiations, their initial concern regarding minorities still looms large.

Emerging as a key sticking point was government disagreement with the Taliban demand of making the Hanafi school of Islamic jurisprudence the guiding principle for framing laws in post-conflict Afghanistan. The government expressed concerns that a Sunni interpretation of Islamic law or the sharia might be considered discriminatory by the Shi’ite population that constitutes 15% of all Afghans.

The contentious issue, as per recent reports quoting the Chairman of the High Council for National Reconciliation, Abdullah Abdullah, is close to being resolved. And even as the reported development indicates a compromise by Afghan negotiators to overcome an obstacle to direct negotiations, their initial concern regarding minorities still looms large.

On the one hand, the Afghan delegation has voiced its determination to protect the rights of women and other marginalised groups, other well as civil liberties for Afghans at large. On the other hand, while the Taliban have promised to protect women’s rights under Islam, they have refrained from specifying how that guarantee would manifest.

Moreover, the treatment meted out to women during the Taliban rule of 1996–2001, justified by the insurgent group’s fundamentalist beliefs based on a strict interpretation of the sharia, raises concerns about the future of women in Afghanistan, given that the ideological position of the Taliban is unchanged.

The treatment meted out to women during the Taliban rule of 1996–2001, justified by the insurgent group’s fundamentalist beliefs based on a strict interpretation of the sharia, raises concerns about the future of women in Afghanistan.

The larger challenge, under which contentious procedural and ideological issues are subsumed, is that of conflicting end states envisioned by the Afghan government and the Taliban, respectively. As conveyed by senior Afghan leadership, the Ghani government seeks to preserve the values of democracy and sovereignty regardless of the kind of power-sharing agreement that emerges out of ongoing negotiations.

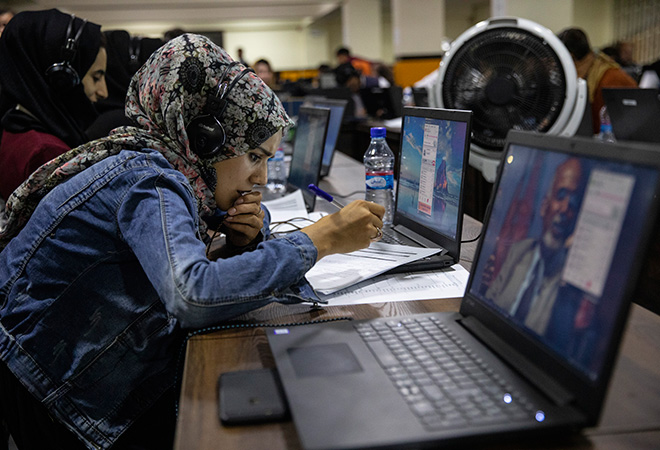

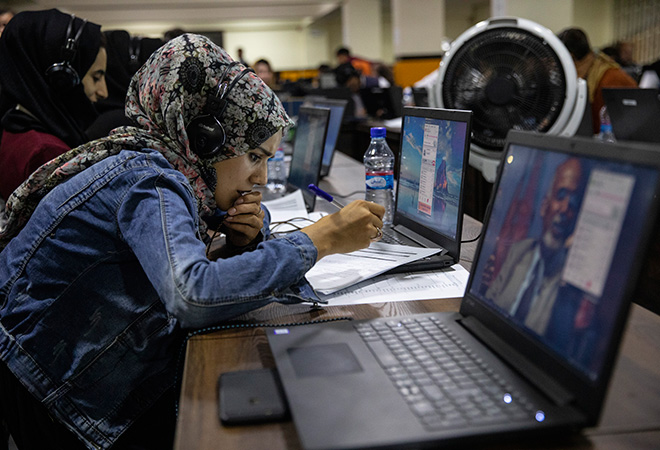

The 2019 Afghan elections saw low turnout amid Taliban threats. Image — A Ghani campaign worker answers phone calls in a call center for irregularities from polling stations. © Paula Bronstein/Getty

The 2019 Afghan elections saw low turnout amid Taliban threats. Image — A Ghani campaign worker answers phone calls in a call center for irregularities from polling stations. © Paula Bronstein/Getty

Contrarily, the Taliban remains staunchly committed to establishing a Islamic Emirate or an Islamic system of governance in Afghanistan. By definition itself, it is impossible to find complementarities in the two divergent views of the state. Although the Afghan delegation in Doha has reportedly been instructed to exercise flexibility in negotiations, President Ghani’s recent meeting with reporters returning from Doha indicated a strong resolve to protect the existing nature of the state, and the “pluralistic and free” nature of Afghan society.

Continued violence

While the Donald Trump administration is determined to withdraw all troops from Afghanistan by mid-2021, the need to maintain a degree of military presence in Afghanistan, even after the official exit, is being widely emphasised. In the absence of US troops, the Taliban will be rendered stronger not only on the battlefield, but also in the political arena.

Given that Taliban violence has continued even as the peace agenda is being pushed by both parties involved, there is no guaranteeing that the insurgent group would mend their ways upon being integrated into the legitimate political structure. In fact, with a significantly reduced presence of foreign troops in Afghanistan, the Taliban would be free to leverage ramped up violence to wrest complete political control of the country from the government.

In the absence of US troops, the Taliban will be rendered stronger not only on the battlefield, but also in the political arena.

Once the US exits from Afghanistan, it would have achieved its primary objective, in line with President Trump’s electoral agenda for the upcoming US presidential polls. For the American endgame in Afghanistan is driven by the need to save face after suffering a military defeat at the hands of insurgents, with or without a negotiated political settlement in place.

Against the background of receding US interest in the peace process, which is likely once US forces withdraw substantially, internal disagreements within the Afghan government, may render the peace process susceptible to breakdown. It is worth noting that senior Afghan leadership, barring a few, was not in favour of hurrying to start negotiations with the Taliban to begin with, but were pressurised with the threat of US aid cuts to expedite the process. Furthermore, even with the talks underway, differing opinions on the contours of a potential power-sharing agreement with the Taliban, and the degree of political compromise acceptable to the government, will likely endure.

While there is no doubt that the Afghan peace process is an opportunity for the country to bring a decisive end to the war and establish peace, achieving that end will not be straightforward by any measure, and will require considerable compromise on either side. However, even if a mutually agreeable end state is devised, the implementation of such an agreement will generate complex challenges of its own.

This essay originally appeared in ORF’s South Asia Weekly.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

The 2019 Afghan elections saw low turnout amid Taliban threats. Image — A Ghani campaign worker answers phone calls in a call center for irregularities from polling stations. © Paula Bronstein/Getty

The 2019 Afghan elections saw low turnout amid Taliban threats. Image — A Ghani campaign worker answers phone calls in a call center for irregularities from polling stations. © Paula Bronstein/Getty PREV

PREV