-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

A comprehensive strategy needs to be adopted to uphold health as an essential human right in conflict zones

Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), a landmark agreement pledged to protect fundamental human rights, completes 75 years on 10 December since its adoption by the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) in 1948. Consisting of 30 articles, the UDHR was drafted by the Commission on Human Rights formed in 1946 under the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). It aimed to enable the international community to prevent the repetition of atrocities witnessed during World War II and complement the United Nations (UN) charter to guarantee the rights of every individual irrespective of race, colour, religion, sex, or any other status.

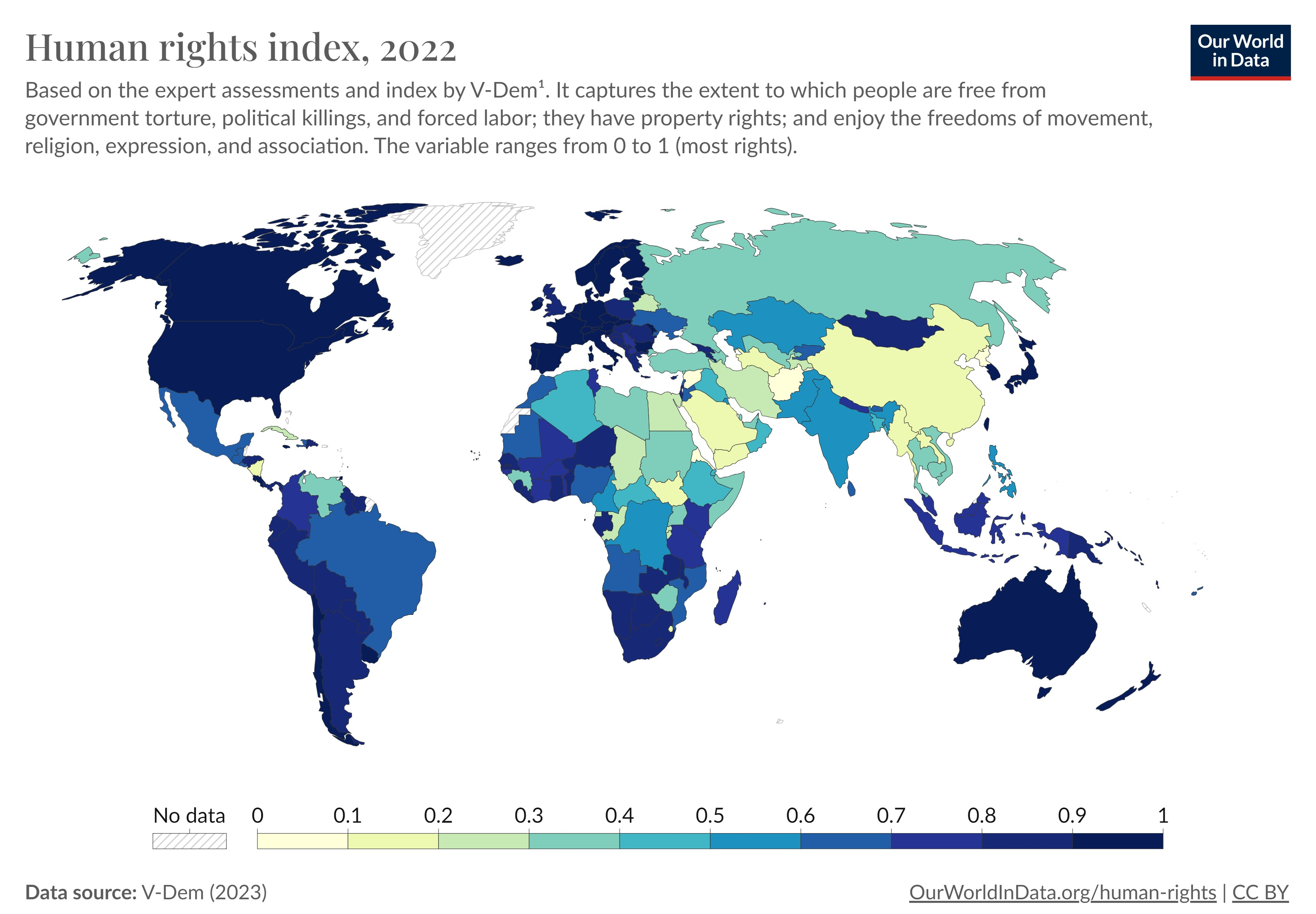

The ongoing conflicts globally have pushed civilians under threat of a never-ending cycle of human rights violations, marked by violence and socioeconomic and political instability, as depicted in Figure 1, which shows the extent to which people experience various human rights, ranging from 0 to 1 (most rights). While the UDHR promotes multiple human rights, including civil, social, and economic rights, the rise of violations has highlighted the need to review the existing frameworks. For instance, the continued conflicts in the Middle East and Europe have recorded wilful killings, sexual violence, and deportation of kids, causing displacement of civilians, especially women and children. Thus, governments worldwide urgently need to work continuously towards alleviating the human rights crises and upholding UDHR’s objective.

Figure 1: Human Rights Index

Source: Our World Data

The escalation of armed conflicts has coincided with increased human rights violations, with data showing that Latin America had the highest recorded cases of human rights defenders killed. The adoption of restrictive laws and decrees by armed groups has led to the denial of humanitarian work and workers, notably in Yemen, Afghanistan, and Sudan. Within these crises, the violence has disproportionately affected children, accounting for 27,180 grave violations in the past year, according to the UN Secretary-General Report. Yemen is regarded as the worst conflict-affected country for children, while Nigeria has the highest number of children at risk of violence.

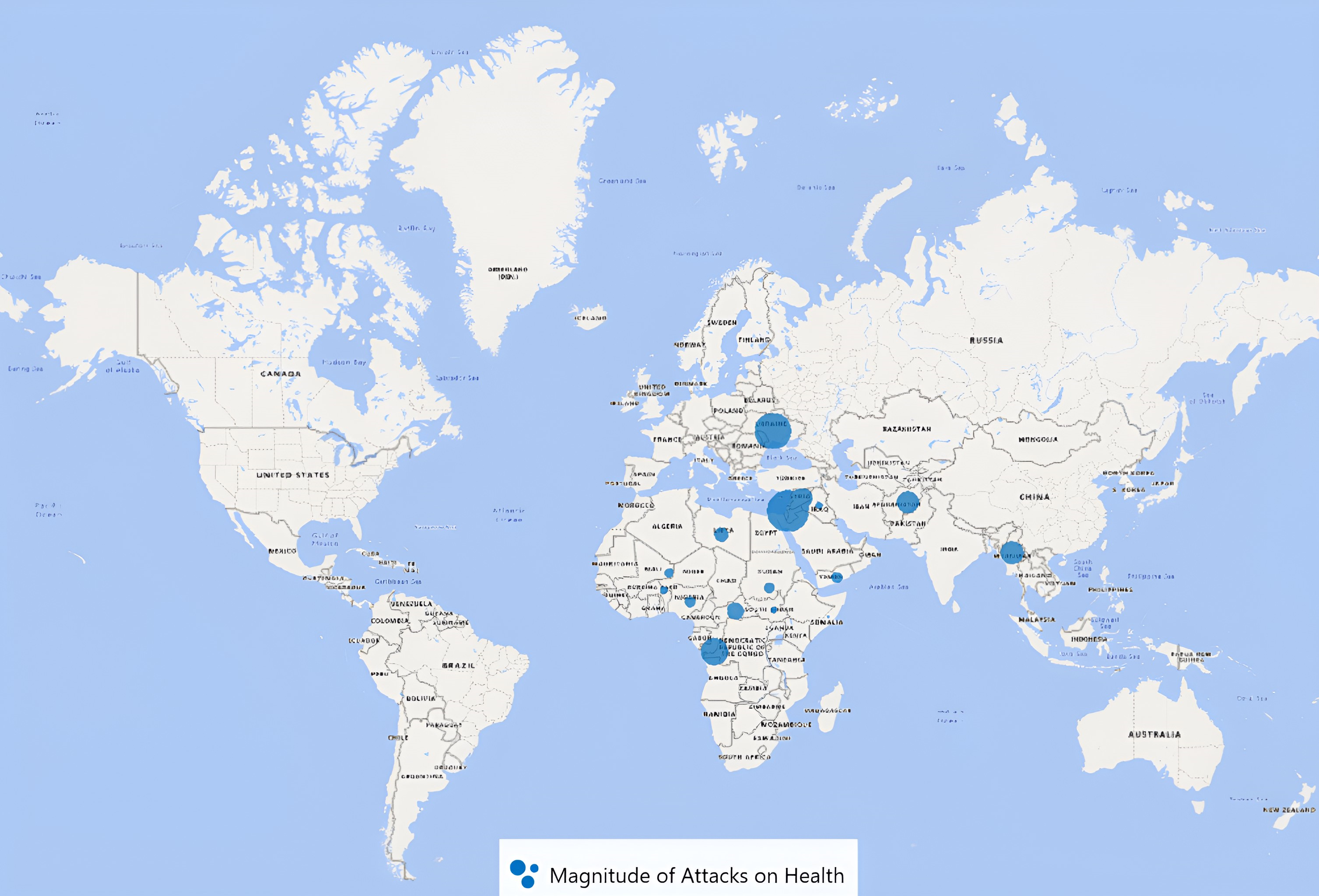

The multifaceted nature of these conflicts has a multidimensional impact on society, including health. The interlinkage of human rights and health is highlighted by the synergy and the prerequisite nature of these two factors. This interdependence is also evident in the constitution of the World Health Organisation, which proclaims health as a fundamental right and extends beyond just healthcare to ensure the underlying socioeconomic and political determinants are addressed to attain the highest standard of physical and mental health. However, civilians are deprived of access to healthcare facilities, with an emerging trend of healthcare facilities and workers becoming the targets. Figure 2, highlights regions that witnessed the attack on health between January 2018 to December 2023. Therefore, it becomes imperative to view health as a fundamental human right for achieving UN SDGs 3 and 16, among others.

Figure 2: Magnitude of Attack on Health

Data Source: Surveillance System for Attacks on Healthcare (SSA)

The UN has embraced a multitude of human rights resolutions, expressing an unwavering dedication to protecting the honour and welfare of people. Pivotal resolutions like the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, the Declaration on Human Rights Defenders, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples are part of their efforts. These directives establish essential guidelines; however, their success largely depends upon a unified determination from states to put them into action and uphold them.

Figure 3: Core Instruments of International Human Rights

Source: Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

The doctrine of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) mandates that the global community step in to halt atrocities such as genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity when a nation fails or shows reluctance to shield its populace. R2P extends to improving health conditions for those trapped amidst hostilities within conflict-torn areas. For instance, during the 2011 Libyan Civil War’s escalating civilian health crisis, the UNSC enacted Resolution 1973, allowing all necessary actions to assure Libyan civilian protection. International entities like the WHO and various NGOs played pivotal roles in curtailing conflict-inflicted health issues, including disease proliferation. Reaching a unified stance on implementing R2P can be complex due to varying national interests. Employing diplomacy and persuasive tactics is key in cultivating an agreement and commitment towards upholding human rights within conflict zones. Diplomatic engagements with influential parties, particularly powerful neighbouring states, are vital for securing backing for intervention measures.

Protracted conflicts incite damage to combatants and civilians due to the breakdown of social order. Thus, the intricate interplay of health, peace and conflict can be tackled by using health diplomacy as a tool in humanitarian crises to build resilient health systems. For instance, the United States (US) has extended its medical mission to improve and assist the development of healthcare through education, training, consultation, and scholarly activities. Thus, the use of such diplomatic interventions ensures continued access to health. Further, it also helps in the capacity building of the local ecosystem, as in the case of the BENAA Project in Egypt, to support the implementation of different human rights instruments.

Employing diplomacy and persuasive tactics is key in cultivating an agreement and commitment towards upholding human rights within conflict zones.

Enhancing the coordination between multiple actors of global health, development, and aid providers through humanitarian diplomacy is critical to building an effective overall response. The coordination could be improved by the inclusion of health actors into the working groups operating in these settings. Such a measure could strengthen the knowledge of the humanitarian workers on disease surveillance, preparedness, and response. This approach was seen in Mali where the WHO and International Medical Corps initiated and led a health cluster with the Ministry of Health and around 35 international Non-profit organisations. Similarly, including humanitarian workers during assessments can help better evaluate measures as they can leverage their knowledge about the specific health needs and response strategies to implement interventions effectively. Additionally, humanitarian diplomacy provides a space for discussion, decision-making, and cooperation, which could help relieve suffering, ensure livelihoods, and defend vulnerable groups’ fundamental rights, including health.

In conclusion, effectively upholding health as an essential human right in conflict zones requires a comprehensive strategy. This involves navigating complex sovereignty issues, implementing security protocols, and fostering collaboration among all parties involved. Pathways should also be made to ensure ease of access, persistent rebuilding activities, and nuanced political diplomacy. After conflicts have ceased, extensive efforts to rebuild must include restoring medical facilities, training healthcare workers, and supporting the mental recovery of populations. To build lasting solutions beyond immediate health emergencies, prioritising sustainable investments in making healthcare infrastructures resilient and proficient is essential. Consequently, it is imperative to critically evaluate current policies and remodel actions based on empirical evidence that reflects socioeconomic and cultural contexts. The Pandemic treaty currently in discussion could potentially play an instrumental role in fortifying health systems which can lead to adopting new efficacious strategies. It is such dialogues and forums that help towards achieving health as a fundamental human right which was reiterated by Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General, WHO.

Kiran Bhatt is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Health Diplomacy, Department of Global Health Governance, Prasanna School of Public Health, Manipal Academy of Higher Education.

Poornima is a Junior Research Fellow and Doctoral Candidate at the Department of Geopolitics and International Relations, Manipal Academy of Higher Education.

Sanjay Pattanshetty is a Professor and the Head of the Department of Global Health Governance and Coordinator of the Centre for Health Diplomacy at Prasanna School of Public Health, Manipal Academy of Education.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Kiran Bhatt is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Health Diplomacy, Department of Global Health Governance, Prasanna School of Public Health, Manipal Academy of ...

Read More +

Dr. Sanjay M Pattanshetty is Head of theDepartment of Global Health Governance Prasanna School of Public Health Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE) Manipal Karnataka ...

Read More +