Inclusive Wealth (IW), reflecting the social value of collective well-being, has gained traction as a comprehensive measure of prosperity, surpassing the limitations of traditional accounts like the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). First proposed by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and United Nations University - International Human Dimensions Programme (UNU-IHDP), the IW framework encapsulates the sum of a country’s natural, human, social, and physical capital. This concept takes on additional significance in India, given the country's diverse socio-economic fabric and the need for an all-encompassing wealth assessment model.

India’s shift towards an inclusive approach

The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has been the shorthand for economic success for decades, yet its focus on short-term output obscures more than it reveals. It neglects the environmental costs of growth, the social value of natural resources, and the widening chasms of socio-economic inequalities. In India, rapid GDP growth has lifted millions out of poverty, yet the accompanying environmental degradation and resource stress pose significant threats to long-term prosperity. A 2014 World Bank study estimated that environmental degradation costs India about 5.7 percent of its GDP annually, indicating a dire need for a metric that accounts for ecological and social dimensions of growth.

Rapid GDP growth has lifted millions out of poverty, yet the accompanying environmental degradation and resource stress pose significant threats to long-term prosperity.

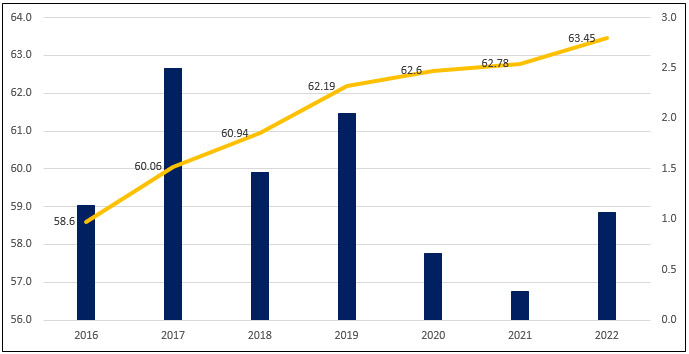

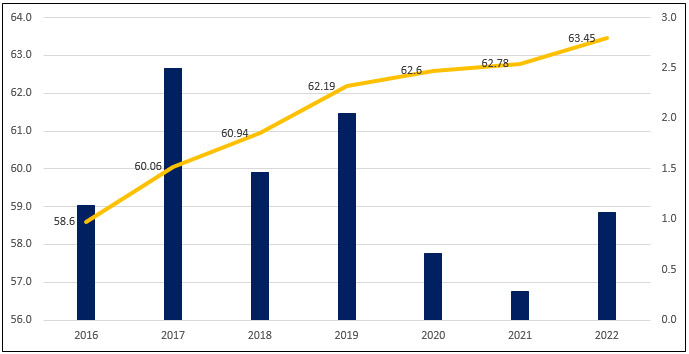

In recognition of GDP's blind spots, the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Index emerged as a broader barometer of development, yet it remains a measure of progress, not the long-term accumulation of assets. Since adopting the 2030 Agenda in 2015, India’s SDG index scores have increased from 58.6 in 2016 to 63.45 in 2022. However, the rate of progress has been somewhat erratic, ranging between a 2.5 percent increase in 2016-17 and a 0.3 percent increase in 2020-21. In fact, despite overall progress, India is only on track to achieve 34 percent of the SDG targets, while it has shown severely limited improvement along 43 percent of the targets and has been deteriorating on 23 percent of them. The real quest, therefore, is for a dynamic model that reflects the nation's wealth accumulation in all its forms and not just the flow of goods and services year-on-year.

Figure 1: Progress in India’s SDG Scores (out of 100)

Source: Authors’ own, data from: SDSN SDG Dashboard

Here, inclusive wealth, with its emphasis on the stocks of capital assets, offers a promising alternative. It marks a paradigm shift that values sustainability and inclusive well-being alongside economic activity and developmental progress. This holistic metric encompasses natural capital, such as forests, minerals, and ecosystems; human capital, including education and health; and produced capital, like infrastructure and machinery. The UNEP's Inclusive Wealth Report (IWR) 2018 positions IW as a critical tool for sustainable policy-making, offering a lens through which to view a nation's capacity for generating both intragenerational and intergenerational well-being through achieving the SDGs.

India's growth narrative has been predominantly GDP-centric, often overshadowing sustainable and inclusive development concerns. The IWR 2023 reveals a complex picture: while India's physical capital has steadily increased and human capital stock remained relatively stable between 2000 and 2019, its natural capital has declined. A US$ 1,222 per capita cost as the net impact of environmental degradation has significantly offset the US$ 1,765 per capita welfare valuation of SDG progress over the period. Such trends have raised alarms about the sustainability of India's growth and development trajectory, highlighting the urgency of integrating IW into the nation's economic planning and policy discourse.

The IWR 2023 reveals a complex picture: while India's physical capital has steadily increased and human capital stock remained relatively stable between 2000 and 2019, its natural capital has declined.

As a positive move towards this, the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MOSPI) initiated the compilation of green wealth accounting under the Natural Capital Accounting and Valuation of Ecosystem Services (NCAVES) project in 2017, aligned with the System of Environmental and Economic Accounting (SEEA) framework. The leap from GDP to SDGs and now to Inclusive Wealth is more than methodological; it is a shift towards a future where the sustained accumulation of wealth-generating capital assets, and not only sustainable development, is the cornerstone of national prosperity.

SDG progress and inclusive wealth across Indian states

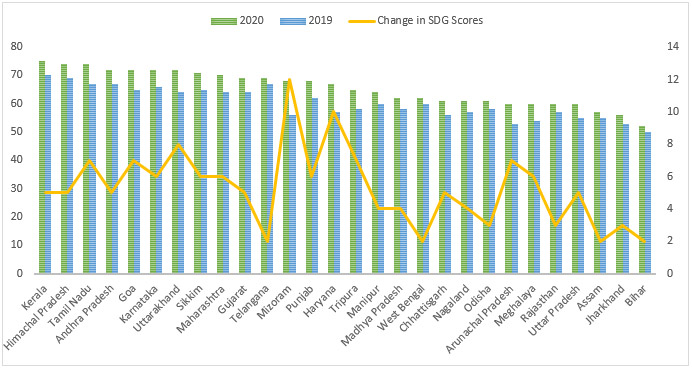

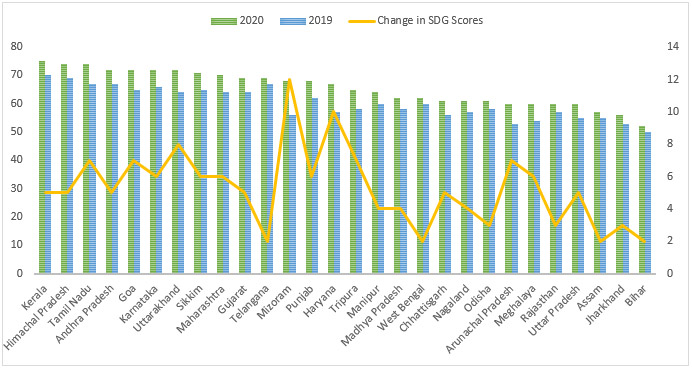

At the sub-national level, achieving or pursuing the various targets under the 2030 Agenda has also witnessed differential success. The assessment of the SDGs' progress across Indian states shows that while the Northern or Southern regions have performed significantly well, most East and North Eastern states have continued to lag. Moreover, across states, the rate of progress has been inconsistent, with very few states showing significant improvement in SDG scores, while some others have only exhibited minor deviations from the previous year.

Figure 2: SDG Scores and Rate of Progress across Indian States (2019-2020)

Source: Authors’ own, data from: NITI Aayog SDG Dashboard

The vast disparities across Indian states necessitate a localised approach to wealth assessment that can help monitor the contribution of this progress along the SDGs to the long-term sustainability of development processes. There is no subnational Inclusive Wealth measure for subnational monitoring in India. Developing such an index, grounded in physical, natural, and human capital specifics across different regions, can illuminate the disparities and drive targeted policy interventions.

India's quasi-federal structure post-independence has evolved to include the concepts of cooperative and competitive federalism. In competitive federalism, states compete to attract finance and investment in order to foster economic efficiency and enhance developmental activities. The IW assessment can serve as a critical tool in this context, enabling a better understanding of how states utilise their resources, which may contribute to their overall wealth accumulation over time.

The vast disparities across Indian states necessitate a localised approach to wealth assessment that can help monitor the contribution of this progress along the SDGs to the long-term sustainability of development processes.

For policy-making, IW provides a more detailed view of a state's wealth, considering its natural, human, and produced capital. This broader perspective can guide more effective allocation of resources and development planning. Moreover, the regional diversity in IW across India necessitates a precise spatial and temporal approach to subnational IW assessment. A state-wise analysis of specific SDG targets in India reveals significant disparities. For instance, states like Punjab, Haryana, and Kerala have shown lower proportions of individuals living below the poverty line, while states like Orissa and Bihar have higher levels of poverty. These disparities underscore the need for an IW approach to understand and address each state's unique challenges and strengths.

The IW approach provides a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of wealth and development, essential for India's diverse and complex socio-economic landscape. By incorporating factors beyond GDP, IW can help India's journey towards sustainable development objectives, fostering more equitable and balanced growth across its states.

Soumya Bhowmick is an Associate Fellow at the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy, Observer Research Foundation.

Debosmita Sarkar is a Junior Fellow with the Sustainable Development and Inclusive Growth Programme Centre for New Economic Diplomacy at Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV