-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Linked to every job that we do for which we get paid is a job that the customer wants done. Businesses run because customers buy products despite whatever may be getting “disrupted” in the economy. Look closely and you’ll find that customers don’t really ‘buy’ but rather they ‘hire’ your product to solve some specific problem of theirs.

Times Square — a new series on jobs, automation and anxiety from the world's public square.

Read part 2 ► Group instinct & the white tribals of America

Read part 1 ► Where the gig worker fits inside the firm

Some words, more than others, carry a strong scent of their place in popular culture. Disruption is one such catchall of our times, peddled by flame throwers from every trade, badgering us humdrum folks to upend something — anything.

If you’re not officially ‘disrupting’ or ‘disrupted’, there goes your chance to yammer at disruption conferences.

We’re told loudly and often that (fickle) consumer trends and political upheaval mean it’s time to huddle in collective alarm like never before. Hmm.. really?

Does labeling a trend as “disruptive” make it so because it is the product of, say, the digital age where platforms are instant and free on a scale that was unimaginable till even the late 1990s?

Hold that thought. Riding on a free and instant platform makes the platform disruptive and those who ride on it are merely users, not ‘disruptors’, unless we are building businesses on top of it — like how Amazon and MOOCs have been built on the internet or the Angry Birds phenom on the IoS.

"Riding on a free and instant platform makes the platform disruptive and those who ride on it are merely users, not ‘disruptors’, unless we are building businesses on top of it."

Taken out out the realm of clever word play and put to the test of open markets, there’s a discipline in the usage and practice of disruptive strategy for those who believe in more than just fire and brimstone.

Disruption is not monolithic, it has a rubric depending on whether customers are underserved, overserved or willing to pay for a high quality product where low quality products are simply not making the grade.

Harvard professor Clay Christensen explains the case of a leading fast food chain in the US which wanted to add zing to milkshake sales. They did the usual stuff, they called in (who else) the millennials. The under-30s were asked questions — they spouted their wisdom and nothing happened to sales. When they looked out the shop windows early in the morning, the people who came to buy milkshakes were typically alone and male.

On closer questioning, the most common answer they got was something like: “We need something to do on our boring commute.” These are folks for whom donuts or a banana or a Snickers bar weren’t doing the job. Rather than deep insight like a missed breakfast or a preference for milk products, this was a need to suck on something viscous that would last door to door and not be gone in a flash. With this aha! moment, the fast food chain went to work, thickening its milkshake for the morning commute and changing it for the evening commute when people are in a rush to get home and want a quick gulp.

A job to be done typically starts with the words, “Help me..” “Help me avoid..” or “I need to..”

“The fact that you're 18 to 35 years old with a college degree does not cause you to buy a product. Answers don’t come in the language you expect. People are not going to say we need this or we have this problem. It’s our job to ask and figure out what the job to be done there is,” says Christensen.

A job to be done typically starts with the words, “Help me..” “Help me avoid..” or “I need to..”

The central premise of Harvard professor Clay Christensen’s work ‘The Innovator’s Dilemma’ which appeared in the late 1990s, has been sharply questioned ever since it appeared.

Critics have torn into Christensen’s theories that upstarts can flip incumbents merely by serving less profitable customers and then invading consecutively higher margin businesses.

Way back in the 1960s, mini steel plants (mini mills), unable to take on the giant plants at making the entire class of steel products, entered the re-bar business. Finding margins low enough in that market for it not to matter, the giant plants moved out of this low margin business where the difference between sales and cost of goods was not attractive. This process kept repeating itself until the mini plants began playing for the highest margins. By then it was too late and the big steel plants were killed off in America.

Disruption is not monolithic, it has a rubric depending on whether customers are underserved, overserved or willing to pay for a high quality product where low quality products are simply not making the grade.

Disruption is not monolithic, it has a rubric depending on whether customers are underserved, overserved or willing to pay for a high quality product where low quality products are simply not making the grade.

In this piece, we are focusing on Christensen’s updated toolkit for our times that seeks to answer a fundamental question: When the splendid disruptions of today become tomorrow’s status quo, what happens to the party? How do we continue to make profits?

“By focusing on a customer job to be done,” says the tall and soft spoken Christensen.

The things that people need done don’t change very much over the course of human history. Any rant on “fickle consumer trends” possibly just means someone is not willing to or empowered enough to invest in real time enquiry.

Hiring consultants to tell you how big the market is won’t work because the way data is “organised” is usually past tense. What about what your customers are doing or thinking right now?

"When the splendid disruptions of today become tomorrow’s status quo, what happens to the party? How do we continue to make profits?"

Christensen warns against settling for customer insight via feedback forms and surveys. Get out of your office and roam where your customers might be. You won’t get your magic potion in a day. Dig in, stay there and be patient for the answers, says Christensen. The jobs to be done approach, Christensen says, is not a silo that sits apart from disruption or innovation inside a company, it is at the heart of staying relevant and profitable.

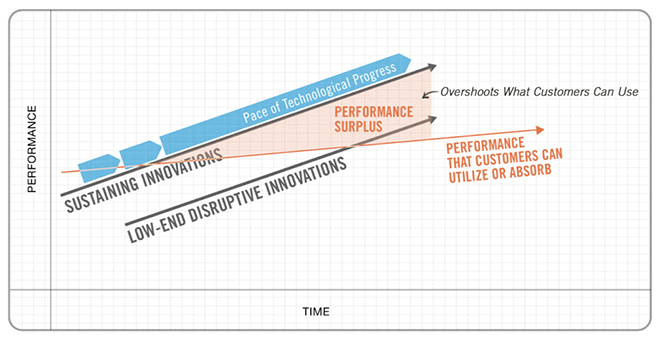

Also, existing business performance typically lags technological progress. Plotted on a graph, underserved customers are below the line segment of existing performance.

In the accompanying graph, in the space between the X axis and performance that users can absorb, there are jobs that need doing and customers to be served. New entrants here will have to make money on lower price per unit sold with a “good enough” performance. New entrants typically win these battles because gross margins are low enough for incumbents not to care — like in the case of mini steel mills entering the re-bar business.

“It’s not so much about buying a product. Customers are hiring you to get a job done.” The challenge for companies, says Christensen, is to become a “purpose brand” for those ‘hiring’ decisions. Like early morning commuters “hired” a milkshake rather than a donut, in our earlier example.

None of this is straightforward, every job to be done has to be blessed by bosses peering at you from within an often grubby and messy organisational chart. Political alignments within the office get in the way, your own place in the hierarchy decides whether the jobs to be done approach gets any face time with the strategy folks or not and so on.

"Every job to be done has to be blessed by bosses peering at you from within an often grubby and messy organisational chart."

Few studies explain the multiple pressures better than the General Motors (GM) — OnStar case.

Chet Huber, before taking on his present job teaching at Harvard Business School, went through the wringer trying to install a technology called OnStar into GM cars that allows the company to develop an ongoing relationship with car owners. It took long, the journey was cumbersome and Huber often wondered why he agreed to hole himself up in Detroit for a project that was burning so much cash. Yet, when Huber stuck it out, the results were sensational. “General Motors spent a billion dollars on my tuition. That was the negative cash flow we invested in OnStar before it turned profitable,” explains Huber.

Disruption is more blind alley and less magic wand. You need to keep circling back to the open road, where wayfarers need stuff fixed. Lessons learnt here can take companies from a dorm room to stock market heaven (Facebook), from noun to verb (Google), it’s how WR Hambrecht pioneered a new auction model for for initial public offerings (IPOs) in the US it’s why BMW and Mercedes are attacking Tesla at its own game in electric cars.

Christensen explains the BMW-Mercedes-Tesla triangle through the lens of disruption theory: “f a new entrant (like Tesla) attempts to enter the high-end of a market as a sustaining innovation then the large, powerful incumbents will attack the new entrant. This is now playing out as we see BMW and Mercedes develop their own electric vehicles. If Tesla would focus on the low-end of the market, they would see a much less fiercely competitive environment.”

"Disruption is more blind alley and less magic wand. You need to keep circling back to the open road, where wayfarers need stuff fixed."

For BMW and Mercedes, Tesla is a threat because it’s angling for the most attractive customers where margins are highest. Powerful incumbents will not budge from this space even if it means they need to add new machinery and technologies to produce electric vehicles.

“It’s not about what to think but how to think that makes the difference between success and failure,” says Christensen. “All strategy is (at best) temporary.”

Some quotes here are the author's personal class notes from Clayton Christensen’s lectures on Disruptive Strategy.

Graph used is from Clay Christensen’s lecture handouts.

Christensen, Clayton; Competing Against Luck: The Story Of Innovation And Customer Choice; Harper Collins.

Huber, Chet; Detour: My Unexpected, Amazing, Life Changing Journey With OnStar; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Nobel, Carmen; Clayton Christensen and milkshake marketing, Harvard Business School

The Tesla killers, Motor Trend.

Google IPO Aims To Change the Rules, Wall Street Journal.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Nikhila Natarajan is Senior Programme Manager for Media and Digital Content with ORF America. Her work focuses on the future of jobs current research in ...

Read More +