This article is part of ORF's Research and Analyses on the unfolding situation in Afghanistan since August 15, 2021.

This article is part of ORF's Research and Analyses on the unfolding situation in Afghanistan since August 15, 2021.

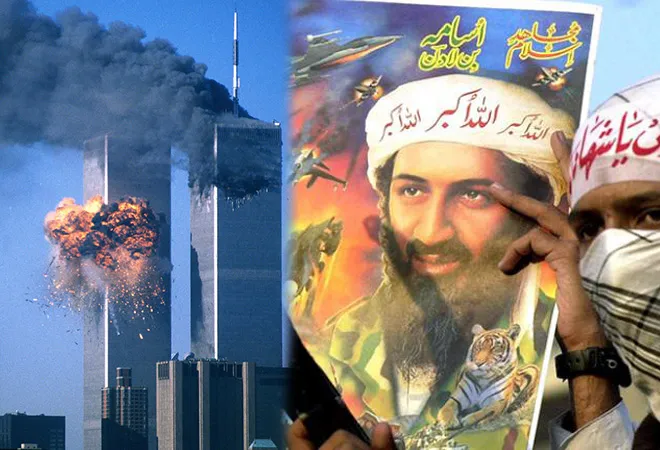

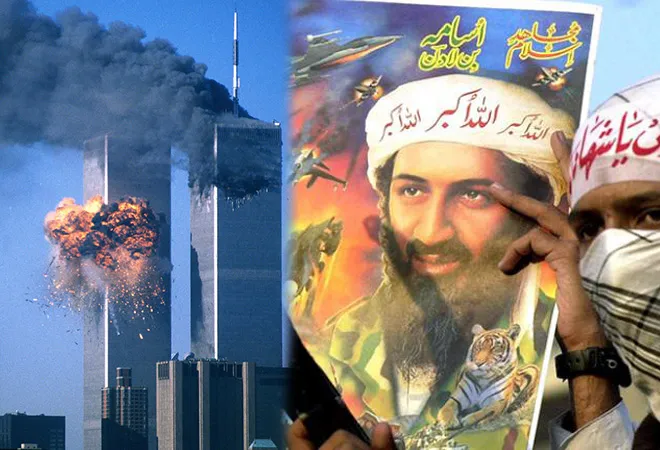

This year marks 20 years since the 9/11 attacks in New York and Washington D.C. that changed global geopolitics in a matter of hours. The terror strikes against the US marked the beginning of a new era, led by a political ideation now known as the ‘War against Terror’, which saw the largest mobilisation of Western military strength, arguably since World War II, as military campaigns were launched in Afghanistan and later in Iraq, followed by covert wars against terror groups across the world.

Over these 20 years, removal of Islamist terror group al-Qaeda, the masterminds behind 9/11, was seen as the one-stop solution to ‘win’ this US-led war against terrorism. Much of this thinking concluded in 2011, after an 11-year long search, when the US found and neutralised al-Qaeda Chief Osama Bin Laden in Abbottabad, Pakistan, which was at the heart of Pakistan’s military establishment.

From the perspective of the ‘War on Terror’ narrative, nothing has been more damning than the return of the Taliban to power in Afghanistan, 20 years after the US military campaign dislodged them and returned the group to the caves of the Tora Bora and back to the construct of an insurgency.

However, terrorism, especially transnational terrorism, has only grown in this period and become more accessible as witnessed by the rise and (debatable) fall of the so-called Islamic State (known as ISIS, ISIL or Daesh in Arabic) in Iraq and Syria over the past few years. From the perspective of the ‘War on Terror’ narrative, nothing has been more damning than the return of the Taliban to power in Afghanistan, 20 years after the US military campaign dislodged them and returned the group to the caves of the Tora Bora and back to the construct of an insurgency.

The timeline is dizzying to grasp. In September 1996, the Taliban had taken over Afghanistan and installed its Islamic emirate. In September 2001, the 9/11 attacks took place, leading to a US invasion, and in September 2021, the Taliban walked back into Kabul, seized power, re-installed its emirate and was being seen by the US as a possible partner to counter future terrorism threats emitting from the country. Much of the Taliban’s new leadership has been sanctioned by the United Nations (UN) or the US in one form or another—four people in the group’s new caretaker cabinet have served time in Guantanamo Bay, which is almost now being used as a badge of honour by the Taliban; and collectively, the Cabinet Members have US $20 million worth of bounties on them declared by the US itself. This timeline of the Afghan war, as absurd as it looks and sounds, is expected to have significant consequences regionally, with its immediate effects felt in South Asia and eventually across the globe. US Senator Lindsay Graham recently assessed that the US would have to go back into Afghanistan, considering the botched way the superpower withdrew from the conflict zone.

The global jihadist terror threat’s sustainability despite decades of counterterror measures, ranging from overt to covert, truly plays out the cliché that ideologies cannot be beaten only using guns and bombs, but guns and bombs can be used to embolden radical ideologies even further. However, as the world moves forward into a more precarious stage of counterterrorism once again, a significant level of reflection on the past is needed to course correct the very ideation of the ‘War on Terror’, which was led by a knee-jerk reaction in the aftermath of 9/11 rather than having an expansive blueprint on what needs to be achieved. While this did, indeed, diminish groups such as the al-Qaeda up to a point on the one hand, on the other, it enabled other state actors such as Pakistan—which uses Islamist ideologies as a state tool in theatres such as Afghanistan in return for access, help, monetary benefit, and other deliverables instead of dismantling terror infrastructure within its own territories. Of course, for Islamabad, the ultimate endgame is to keep India’s influence out of Kabul.

US Senator Lindsay Graham recently assessed that the US would have to go back into Afghanistan, considering the botched way the superpower withdrew from the conflict zone.

The future of the now fast evolving and developing Islamist terrorism threat can be investigated from three fronts: Strategic, tactical, and political.

Strategic: The very strategy of counterterrorism, led by an idea of interventionism, needs a re-work. States that have been on the receiving end of such thinking from Western powers—Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Libya, and others—are today home to not just one, but many extremist and terror movements. However, a trail of failed states created by counterterror thinking and actions over the past two to three decades pose a larger challenge rather than solving previous ones. Capitals across the world have, most importantly, diverged away from counterterrorism being a homogenous, or a global action, which was the case in the ensuing months after 9/11 at least. Great powers’ games eventually took precedence. The extremism translated by the West in Libya, via erstwhile leader Muammar Gaddafi’s regime, was seen as an opportunity by Russia and Turkey a few years later. The “negotiated” US exit from Afghanistan, a country now flushed with Western arms and ammunition in the hands of the Taliban, which in turn will eventually trickle down to the likes of al-Qaeda, Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP), and others, is to remain a significant challenge in the years to come. Strategic flaws, such as the invasion of Iraq, led by American political whataboutery and intelligence failures that only exasperated the War on Terror should be inculcated as never-to-be-repeated mistakes. These flaws have undermined the counterterrorism narratives more than the likes of Taliban, al-Qaeda, and others. From the outset, counterterror goals need to be institutionally untangled from nation building, and the onus for the same should be applied on host states, instead of using host states to play double roles (or more in some cases).

Techniques such as drone strikes, leadership decapitation, overwhelming use of military power (such as MOAB) has shown to be effective, but in a limited capacity, with arguably more severe long-term ideological fallouts compared to short-term tactical gains.

Tactical: The US-led war on terror went much beyond just the Afghanistan and Iraq theatres, following the expansion, and not the expected contraction, of the threats. Techniques such as drone strikes, leadership decapitation, overwhelming use of military power (such as MOAB) has shown to be effective, but in a limited capacity, with arguably more severe long-term ideological fallouts compared to short-term tactical gains. The Afghan war showcased the severe ills of ‘outsourcing’ important sections of wars to private sector contractors and accountants. The expedited US withdrawal led by a myopic vision of President Joe Biden led to the decapitation of not the terror leaderships, but institutions such as the Afghan Air Force, a critical component of fighting against the Taliban. The outcome of a conflict is dependent on how clear the aims are. Broad aims, or no aims—as many accounts have highlighted was the case in Afghanistan—particularly after 2011, has led to a cyclical conflict which eventually fell victim to the Taliban “having the watches”, while Western forces were bound by increasing shortage of time.

Political: The Arab Spring was a watershed moment in more than one sense. While it emboldened voices for democracy in the Middle East, it also pushed extremist ideologies in the region and beyond to double down. This popular revolution, which started in Tunisia and then spread across the region, toppling many authoritarian regimes, also made Islamist ideologies work to strengthen their own movements, seeing the ‘threat’ of democracy as another Western intervention to regroup around. And up to a certain extent, this was done successfully. The very concept of external kinetic ‘political management’ of states should be replaced with outright diplomatic methodologies, even if they take longer than disrupting a situation using military means. And military and tactical options, should be largely moved to the covert theatres. Counterterrorism’s overwhelming use of traditional military strength as a solution has showcased its severe limitations, most visible in Afghanistan, and the fact that the US had to ultimately sign an exit deal with the Taliban, so that the latter can let the US exit peacefully.

Africa is already being highlighted as the next big geography to fall under the influence of Islamist extremism while the Middle East and South Asia are expected to witness resurgent Islamist movements.

The threat of transnational terrorism will only see an uptick in the years to come. Africa is already being highlighted as the next big geography to fall under the influence of Islamist extremism while the Middle East and South Asia are expected to witness resurgent Islamist movements. The so-called Islamic State made more of an impact on both terror and counterterrorism thinking in the mere five years of its prime, which included setting up a caliphate at a point geographically as large as the United Kingdom, than the likes of al-Qaeda which has ned for over three decades. In return, the counterterror narrative in the US moved from ‘War on Terror’ to the condition of ‘Forever Wars’, the latter leading to domestic political compulsions of winding down post-9/11 counterterror policies with their successes and failures up for equal debate.

The Taliban victory in Afghanistan has the potential of becoming the biggest ideological war-cry for Islamist terror organisations in the time to come. And with the increase in the line-up of fractured, failed, and frail states left behind by Islamist insurgencies, the threat in the next decade has only increased instead of decreasing.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This article is part of ORF's

This article is part of ORF's  PREV

PREV