The current Chinese leadership seems fairly optimistic in its effort to reshape the country’s global profile in a bold and creative way––a key element of which is to build up an economic system with China at the centre of it. Undoubtedly, the proposal of reviving the ancient Maritime Silk Road (MSR) demonstrates this innovative approach. The 21st century Maritime Silk Road, together with the Silk Road Economic Belt, has emerged as a signature foreign policy initiative and is the first global strategy for enhancing trade and ‘fostering peace’ proposed by the new Chinese leadership under President Xi Jinping. This paper discusses the Chinese rationale behind the MSR proposal and examines where it fits in China’s ‘grand strategy’. In so doing, it also analyses the potentials and challenges of the MSR.

21st Century Maritime Silk Road

China has proposed to revive the centuries-old ‘Silk Road of the Sea’ into a 21st century Maritime Silk Road. This proposal has attracted enormous interest among policy makers and scholars. Is there a confluence of maritime interests or is the idea to revive the Silk Road of the Sea an instrument of Chinese ‘grand strategy’? Grand strategy denotes “a country’s broadest approach to the pursuit of its national objectives in the international system”.<1> A state’s grand strategy provides an understanding of its long-term foreign and security policy goals. One important aspect of China’s grand strategy is ‘strategic access.’<2> China is going out in search of natural resources and developing overland transport networks in pursuit of its national interest. As part of its strategy, China is developing roads, railways, ports, and energy corridors through its western region, across South Asia and beyond.<3> The idea of reviving the MSR manifests Chinese innovative approach and its grand strategy.

Why strategic access or the politics of routes is so important to China? The politics of routes in South and Southeast Asia has played a key role in the region’s military affairs, in political development, economic growth, and cultural change. It enhances an understanding of the nexus between security and development issues. Routes are “the means for the movement of ideas, the dominant culture and ideology of the political centre, to its peripheries”.<4> Routes can define the territorial reach and physical capabilities of the state and are integral to the achievement of its political, economic, and military potential.<5>Control over and expansions of routes are important to obtain optimum economic benefits from trade with other states. To increase their economic productivity, security, and market size, states may also form integrated regional groupings in which conditions of access are eased for member-states relative to non-members. Such regional integration policies often involve the joint expansion of physical channels of communication and transport. Moreover, maritime access plays a significant role in the formation of strategic alliances and security ties. The proposal to revive the MSR should be seen in this light. This initiative aims to seize the opportunity of transforming Asia and to create strategic space for China.

The MSR in its New Avatar

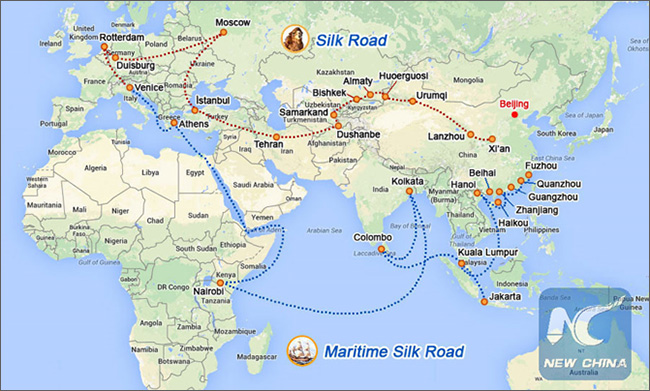

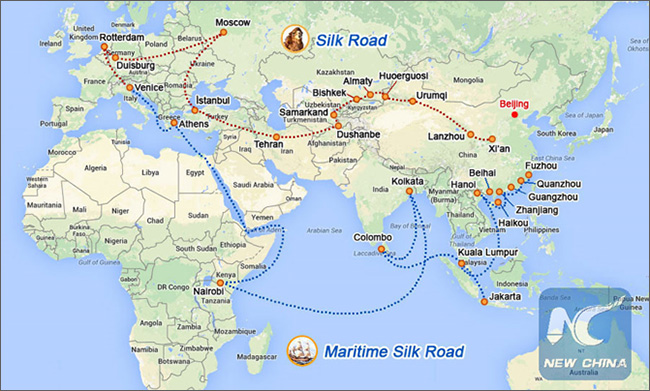

The idea of the MSR was outlined during Chinese President Xi Jinping’s speech in the Indonesian Parliament<6> and Premier Li Keqiang’s speech at the 16th ASEAN-China summit in Brunei,<7> in October 2013. Chinese leaders underlined the need to re-establish the centuries-old seaway as the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. The main emphasis was placed on stronger economic cooperation, closer cooperation on joint infrastructure projects, the enhancement of security cooperation, and the strengthening of maritime economy, environment technical and scientific cooperation. The figure below gives a glimpse of proposed Silk Road. The MSR will begin in Fujian province and pass Guangdong, Guangxi, and Hainan before heading south to the Malacca Strait. From Kuala Lumpur, the MSR heads to Kolkata and Colombo, then crosses the rest of the Indian Ocean to Nairobi. From Nairobi, it goes north around the Horn of Africa and moves through the Red Sea into the Mediterranean, with a stop in Athens before meeting the land-based Silk Road in Venice. In a new map, South Pacific has also been included. So, there are two directions of the MSR– one from China through the South China Sea to the Indian Ocean coastal ports, extending to Europe; the second is through the South China Sea from the Chinese coastal ports extending eastward to the South Pacific.

Figure 1 - The Proposed Route of the Belt and Road

Source: Xinhua at http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2016-04/17/c_135286862.htm

Source: Xinhua at http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2016-04/17/c_135286862.htm

Aims and Objectives of Reviving the MSR

The MSR emphasises connecting the Asia-Pacific economic circle in the east and the European economic circle in the west by building a network of port cities along the Silk Route, linking the economic hinterland in China. According to one report<8>, the Belt and Road Initiative is currently the longest economic corridor with greatest potential in the world––directly impacts 4.4 billion people, around 63% of the world’s population, and deals with an economic aggregate of $21 trillion, 29% of the global volume. Besides, it aspires to improve the Chinese geo-strategic position in the world. According to the “Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road”<9> issued by the Chinese government, the essence of the initiative is an inclusive project open to all countries and international organisations.<10> The initiative features five major areas of cooperation––policy communication, road connectivity, unimpeded trade, money circulation and cultural understanding. The Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying outlined the aims and objectives of the MSR in following words:

China proposed to build the Maritime Silk Road of the 21st century with the aim of realizing harmonious co-existence, mutual benefit and common development with relevant countries by carrying out practical cooperation in various fields, such as maritime connectivity, marine economy, technically-advanced environmental protection, disaster prevention and reduction as well as social and cultural exchanges in the spirit of peace, friendship, cooperation and development.<11>

The Chinese leadership has promised to transform China through a national rejuvenation in order to realise the “Chinese dream”. Beijing is also responding to the region’s need for investment and development and aims to unlock massive trade potential and bolster economic development through this initiative. It has become a defining strategy for economic outreach to China’s partners. The MSR initiative, in fact, is an attempt to create a favourable international environment conducive to China’s continuing development, and thus, it manifests an important element of Chinese grand strategy. This ambitious initiative will receive funding from seven capital pools, among which, the Silk Road Fund, the AIIB, BRICS Bank, and the SCO Development Bank are likely to play major roles. With full political and financial support from the Chinese government, the Belt and Road Initiative has become one of the key tasks in China’s diplomacy to comprehensively promote this strategy.

The salient points of this Chinese grand strategy can be summarised as follows – first, this strategy reflects a shift from China’s low profile international strategy to a more pro-active international strategy to help shape a new international and regional order. Second, China seeks to reap the benefits of its growing economic power and expanding influence across the globe. Third, the initiative reflects China’s growing confidence and also a response to American ‘pivot’ strategy. Finally, the initiative is comprehensive, focussed and President Xi Jinping’s “pet project.” Through this grand vision, the ambition of China’s new leader is to significantly upgrade China’s status in the world.

Several Chinese scholars claim that the initiative is also part of the new round of China’s “opening up” strategy. China is facing challenges of overproduction and overcapacity, particularly in the steel and construction material sectors. This initiative aims to create more overseas demand, and thus could help in addressing China’s domestic economic problems. There is now a growing need for China to invest more in foreign countries. Labour market is becoming more competitive and cost is going high. So, through this initiative China could aim for its economic restructuring. Moreover, the initiative is expected to drum up development initiatives in the less developed regions of China to narrow income gaps between regions. Also, the initiative could be an excellent overseas investment opportunity for the Chinese private sector.

Advantages of the MSR

The MSR initiative is a manifestation of China’s growing significance in the global arena––economically, politically, as well as strategically. The proposal will boost trade, shipping, tourism and development of maritime infrastructure, and enhance connectivity. It aims to promote better mutual understanding between and among people. By promoting such plan, China seeks to ease its territorial disputes with the ASEAN claimant states in the South China Sea and strengthen mutual trust. The MSR proposal is likely to generate huge economic and employment opportunities. It complements and reinforces ASEAN connectivity. It can provide a channel of overseas investment for Chinese companies and capital, either in infrastructure construction, or in manufacturing and foreign commodity trade and service sectors. Thus, an active cooperation can also narrow the huge infrastructure development gap among ASEAN members. For China, such outward infrastructure investment is important for boosting its manufacturing sectors, addressing its domestic production overcapacity and stimulating domestic economic growth.<12>

Over past few decades, China has emerged as a major maritime power and offering maritime infrastructure development to friendly countries. India needs to make major policy changes to develop maritime infrastructure, offshore resources and exploit these on a sustainable basis. Therefore, the MSR should be seen as a welcome opportunity for India.<13>India can also harness Chinese capabilities to improve its maritime infrastructure, including the construction of high-quality ships and world-class ports. More importantly, it will also help India-ASEAN maritime connectivity that has been languishing due to the lack of infrastructure. India and China can also work together on the Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Response (HADR), with the Indian Navy and the PLA Navy cooperating and developing best operational practices for HADR operations. <14>

In the case of Southeast Asian countries, the MSR initiative offers new opportunities for China and ASEAN to cooperate in many sectors including trade, infrastructure and cultural exchange, etc. In general, Southeast Asian states have welcomed China’s initiative in building the new Maritime Silk Road. China has the experience and technology in infrastructure construction as well as the capital. The MSR could spur the economic development of ASEAN. Besides, it could also promote the people-to-people contact and enhance understanding between China and ASEAN as well as among ASEAN countries. However, there is cautious optimism among ASEAN countries. So far, the MSR has not kicked off in ASEAN. There is a widespread perception in the region that “mutually beneficial” development projects often benefit China more than the host country. Indeed, Chinese MSR initiative is more about deepening ties with regional governments and providing work for Chinese industrial companies. Substantial investment in port facilities and related infrastructure in various locations – including in Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Myanmar and Malaysia – is planned or are underway. It is believed that new, expanded or more advanced capacity will improve connections between sea and land legs of trade movements, raising overall transport efficiency and reducing costs. Though, enthusiasm for the projects under the MSR initiative has been limited in South Asia and Southeast Asia, except Pakistan where projects seem to have limited economic logic.

Challenges

Despite emphasis on economic links, there is a lack of clarity on “how and what” of the Chinese proposal. Overlapping of diverse goals (political, economic and security) and involvement of multi-level actors (central government, provincial governments, think tanks, private sector, bureaucracy) make the initiative highly attractive in China, but leaves much room for confusion to outside observers. ‘Trust deficit’ is another major hurdle in this initiative. There are also concerns about what this implies for broader regional strategic partnerships.<15> China has a very specific understanding of security––what drives it and what it aims to achieve––one that many of the countries on this proposed route would not share. Further, there is some anxiety within ASEAN states over Chinese actions that are often in contradiction to China’s stated intentions of goodwill and peaceful cooperation. For example, China’s recent moves in the disputed territory in the South China Sea. In the aftermath of the South China arbitration case and China’s continued assertiveness in maritime Asia, the big question is: How to deal with China when it’s challenging international laws? Certainly, this episode has not only amplified the ‘trust deficit’ among China and its neighbours but it has also forced countries to take a re-look at their approach in handling ties with China.<16> Therefore, China needs to work harder to explain its proposal if trust of countries in South and Southeast Asia were to be gained.

Governance in many countries and regions on the route of this proposed initiative is weak. There could always be political and security risks in implementing the project. Change of government or domestic factors may cause significant delays and cost overrun while implementing the various projects associated with the MSR. Sri Lanka and Myanmar are good examples of such problems. Amidst global economic pressure, low economic returns/no economic returns (in short to medium term) from projects under this initiative will put further pressure on the slowing economy.

Conclusion

While the MSR proposal is an innovative idea and aims to create opportunities and bring peace and stability, it is still an unfolding idea. China’s maritime renaissance, however, is being led by its dynamic commercial sector, with maritime business leading the way. Naval development is following the merchant marine development. China’s path to the sea is different, distinguished by seaborne commerce leading the way, trailed by naval development.<17> After two decades of rapid growth, Beijing is again looking beyond its borders for investment opportunities and trade. As China rises, with the sea as its main highway for incoming investment, technology and outgoing exports, China is studying the past and thinking about the future. The MSR places China in the ‘middle’ of the “Middle Kingdom” mindset and is an effort in initiating a ‘grand strategy’ with global implications. The MSR offers several opportunities for South and Southeast Asia in its new avatar. However, there is scepticism about Chinese stated objectives and its actual intentions. China needs to convince the MSR-impacted nations and regions that the proposal is for win-win cooperation and to do this Beijing needs to engage and listen to other countries and regional institutions to make this initiative more inclusive.

This article was originally published in GP-ORF’s Emerging Trans-Regional corridors: South and Southeast Asia.

<1>Robert H. Dorff, “A Primer in Strategy Development”, in Joseph R. Cerami and James F Holcomb, Jr. (eds.), U.S. Army War College Guide to Strategy, Carlisle Barracks, P.A., Strategic Studies Institute, 2001, p. 12.

<2> The term ‘access’ normally subsumes all types of bases and facilities (including technical installations), aircraft over flight rights, port visit privileges, and use of offshore anchorages within sovereign maritime limits. The term strategic access is used more broadly to include, for instance, access to markets, raw material sources, and/or investments, penetration by radio and television broadcasts, and access for intelligence operations. See Robert E. Harkavy, Great Power Competition for Overseas Bases: The Geopolitics of Access Diplomacy, Canada: Pergamon Policy Studies on Security Affairs, Pergamon Press Canada Ltd, 1982, pp. 14-43.

<3>See Rajeev Ranjan Chaturvedy & Guy M. Snodgrass, “The Geopolitics of Chinese Access Diplomacy”, German Marshall Fund of the United States Policy Brief, 29 May 2012.

<4>Jean Gottmann, “The Political Partitioning of Our World: An Attempt at Analysis”, World Politics, Vol. 4, July 1952, p. 515.

<5>Mahnaz Z. Ispahani, Roads and Rivals: The Politics of Access in the Borderlands of Asia, London: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd. Publishers, 1989, p.2.

<6> Wu Jiao, “President Xi gives speech to Indonesia's parliament”, China Daily, 2 Oct 2013, available at http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2013xiapec/2013-10/02/content_17007915.htm

<7>“Premier Li Keqiang Attends the 16th ASEAN-China Summit, Stressing to Push for Wide-ranging, In-depth, High-level, All-dimensional Cooperation between China and ASEAN and Continue to Write New Chapter of Bilateral Relations”, 10 Oct 2013, available at http://www.chinaembassy.org.nz/eng/zgyw/t1088098.htm

<8>See CCTV News, “Understanding China’s Belt and Road Initiative in one minute”, 28 September 2015, available at http://www.cctv-america.com/2015/09/28/understanding-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-in-one-minute

<9>National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), People’s Republic of China, “Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road”, 28 March 2015, available at http://en.ndrc.gov.cn/newsrelease/201503/t20150330_669367.html

<10>So far, China has ignored regional associations that do not include China. This strengthens the impression of mismatch between Chinese stated and actual intentions.

<11>Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hua Chunying’s Regular Press Conference on 13 February 2014, available at http://sc.china-embassy.org/eng/fyrth/t1128254.htm

<12> Yu Hong, “China’s “Maritime Silk Road of the 21st Century” Initiative”, EAI Background Brief, No. 941,30 July 2014, available at http://www.eai.nus.edu.sg/BB941.pdf Also see, “ASEAN welcomes China’s new Maritime Silk Road initiatives”, China Daily, 15 August 2014, available at http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/business/2014-08/15/content_18322921.htm

<13> Vijay Sakhuja, “Maritime Silk Road: Can India Leverage It?”,#4635, 1 September 2014, available at http://www.ipcs.org/article/navy/maritime-silk-road-can-india-leverage-it-4635.html. Also see, Vijay Sakhuja, “The Maritime Silk Route and the Chinese Charm Offensive”, in IPCS Special Focus: The Maritime Great Game India, China, US & The Indian Ocean, p. 6, available at www.ipcs.org/pdf.../SR150-IPCSSpecialFocus-MaritimeGreatGame.pdf

<14> Rajeev Ranjan Chaturvedy, “Xi Jinping’s visit should mark new era in Indo-China relations”, The Economic Times, 10 September 2014.. Chinese state councillor Yang Jeichi proposed a dialogue between the two navies on freedom of navigation and Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Response (HADR) at the 17th Annual Dialogue of the Special Representatives of India and China in New Delhi. See, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, Press Release, “17th Round of Talks between the Special Representatives of India and China on the Boundary Question”, New Delhi, 11 February 2014, available at http://mea.gov.in/press-releases.htm?dtl/22861/17th+Round+of+Talks+between+the+Special+Representatives+of+India+and+China+on+the+Boundary+Question

<15>Arun Sahgal, “China’s Proposed Maritime Silk Road (MSR): Impact on Indian Foreign and Security Policies”, July 2014, available athttp://ccasindia.org/issue_policy.php?ipid=21

<16> Rajeev Ranjan Chaturvedy, “Implications of the South China Sea Arbitration Case”, ISAS Insights, No.338, 29 July 2016, available at http://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/ISAS%20Reports/ISAS%20Insights%20No%20%20338%20-%20Implications%20of%20the%20South%20China%20Sea%20Arbitration%20Case.pdf

<17>Andrew S. Erickson, Lyle J. Goldstein, and Carnes Lord (Eds.), China Goes to Sea: Maritime Transformation in Comparative Historical Perspective, Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2009, p.345.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source: Xinhua at http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2016-04/17/c_135286862.htm

Source: Xinhua at http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2016-04/17/c_135286862.htm PREV

PREV