The Rationale

Southeast Asia and East Asia regions are already well-known economic success stories, which emanated from most of the countries in these regions adopting an outward-looking strategy with trade-oriented growth and signaled to potential investors their openness to encouraging FDI flowing in from developed countries from within Asia & elsewhere.

The South Asia region is a relative latecomer to dynamic regional growth that was perceived largely as impeded by inadequate/ very poor infrastructure, high levels of regulations & trade barriers. Linking up South and Southeast Asia has figured in the political thinking of leadership in both regions, but somehow the conditions until recently were not conducive to embarking on such venture. The post-colonial isolationist attitude of Myanmar was a big impediment to its taking advantage of its naturally configured geo-strategic bridge between South and Southeast Asia. Developments in Myanmar after it joined ASEAN translated into economic reforms that gradually eased the restrictions and selectively opened its economic landscapes. The recent elections in that country signal the beginnings of a political transformation, therefore, now offer renewed hope of facilitating linking of the two regions.

However, conditions are not equally conducive at the moment for South Asian region’s westward linking with Iran and Central Asia.

Figure 1: Map of South and Southeast Asia

Source: Nations Online Project at http://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/map_of_southeast_asia.htm

Source: Nations Online Project at http://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/map_of_southeast_asia.htm

A Fractured Saga!

Trade and connectivity are handmaidens to each other, anywhere. However, in the South Asian region, Land and rail connectivity have remained hostage to the negative post-Partition political syndrome. Although road and rail corridors had been long identified by the UN ECAFE/ESCAP decades ago in its Trans-Asian Highway and Railway scheme presented to member governments concerned, progress remained excruciatingly slow – and painful, particularly within the SAARC region. Within the SAARC framework also, while senior officials, after many years of hard, and often fruitless consultations and negotiations, finally managed to cobble together a consensus draft regional Motor Vehicles Agreement (MVA) in 2014, their result did not pass political muster by some and efforts to get an all-SAARC endorsement of the SAARC Motor Vehicles Agreement at Kathmandu Summit in November 2014 was stonewalled by Pakistan. Following this disappointment, some of the SAARC countries, namely Bangladesh, Bhutan, India and Nepal (BBIN) in the eastern sub-region decided that their economic development aspirations that required increased physical connectivity across borders to boost trade, could not be allowed to be held hostage by some and decided to try and get a framework agreement in place at sub-regional level. Senior officials of the four countries met in January 2015 and put final touches to a draft MVA for the BBIN sub-region (essentially along lines of the draft SAARC MVA that had aborted earlier at the summit, and declared that others in the SAARC region (or beyond) could join as and when they were ready. On June 15, 2015, at a Ministerial meeting convened in Thimphu by Bhutan, the Ministers concerned from the four countries signed the BBIN MVA. Trial runs for passenger and cargo vehicles commenced in November, and Standard Operating Procedures tested and completed by end-December 2015. It allows the four signatory countries to move forward with implementation of land transport facilitation measures amongst themselves, exchanging traffic rights easing greatly the rites of passage across borders crossings by passenger and cargo vehicles, thus promoting increased people-to-people contacts, trade and economic exchanges between the four countries. The framework document signed is, ab initio, of a bilateral nature in practice, on the basis of reciprocity. For every vehicle one country allows another co-signatory to enter its territory, makes it incumbent upon the recipient country to reciprocate in equal measure. Passengers will still be subject to prevailing immigration requirements of countries and goods are subject to payment of taxes and levies as exist. Nevertheless, this is a very positive and historic development within the region, and paves the way for progressive easing of restrictions on ease of movement of vehicles, goods and peoples across the borders of the four countries. The BBIN MVA will become fully operational as soon as ratified by the respective parliaments of the signatory states.

BIMSTEC and BBIN

India’s earlier “Look East” policy, now metamorphosed by current Prime Minister Modi’s government into the “Act East” initiative, may be viewed as mirroring ASEAN’s “Look West” aspirations and is aimed to link up with the latter and beyond to East Asia. The BBIN sub-grouping of SAARC and its recent efforts to put in place and operationalize enhanced connectivity amongst them is an essential first step towards actually operationalizing the “Act East” initiative. The BIMSTEC (Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation), that was formed in the late nineties, and includes the BBIN countries as well as Sri Lanka, Myanmar and Thailand, could well also embrace the ongoing BBIN initiatives and play the bridging role between the SAARC and ASEAN regions. The progression along this pathway has been slow but organically enlarging. The BBIN achievement could not have happened without the upswing in Bangladesh-India relations since 2010 that put in place the critical stepping-stone for forging forward. In other words, it first required Bangladesh and India getting their relations right before meaningful connectivity aspirations, between and beyond them could be envisaged or embarked upon.

Road and Rail Corridors

ESCAP, ADB and other multilateral donors had assisted the SAARC countries over many years, to identify a number of road and rail corridors to facilitate trade and movement of people. The BBIN MVA will (or should effectively) enable these four countries to now work together with a sense of purpose for operationalizing, in stages, the following identified road corridors, first among them and then extending beyond them to the east and linking with Myanmar (and thence with the ASEAN corridors);

- SAARC Corridor 4: Kathmandu (NP)-Kakarbita (NP)-Panitanki (IN)-Phulbari (IN)- Banglabandha (BD)- Mongla-Chittagong (BD)

- SAARC Corridor 8: Thimpu (BH)-Phuentsoling (BH)- Jaigon (IN)- Changrabandha (IN)- Burimari (BD)- Mongla/Chittagong

- Asian Highway 2: NE India- Myanmar

- Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project: Mizoram (Mobu)-Sittwe (Myanmar)

Additionally, Bangladesh and India are collaborating on linking up existing national highways at Dalu (Meghalaya, India)-Nakugaon (Mymensingh, Bangladesh) – thus establishing a North-South corridor of great importance for Bhutan and the NE states of Meghalaya and Assam in India. Bhutan, in addition, has been increasingly using the ICP at Dawki-Tamabil for the last few years, using less the corridor earlier designated for them (Corridor 8), because of operational difficulties and delays experienced by them. Bangladesh and India have also worked together to upgrade earlier minimal facilities at Bhomra, further south-east of Benapole-Petrapole in a bid to augmenting capacity of the latter, plagued for long by technical and handling capacity glitches.

The operationalization of the BBIN MVA will also exponentially augment the ability of peoples of the four states traveling to each others’ countries in personal or commercial transport vehicles. It may be mentioned here that prior to this development, passenger bus services as follows:

- Kolkata-Dhaka-Agartala (operational)

- Dhaka-Sylhet-Shillong-Guwahati (operational)

- Dhaka-Kathmandu (announced)

- Dhaka-Thimphu(announced)

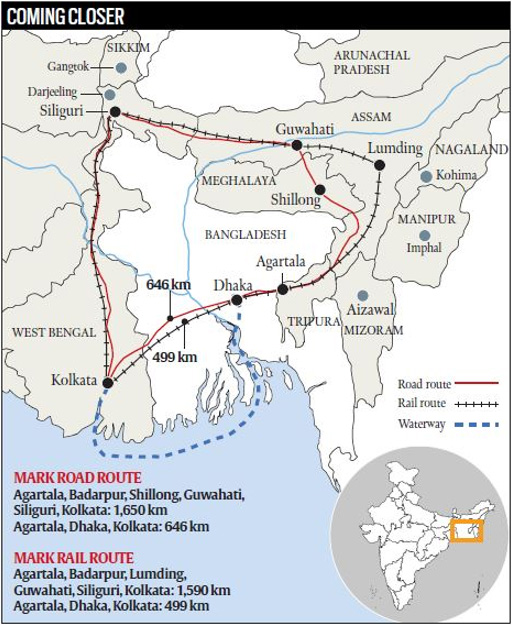

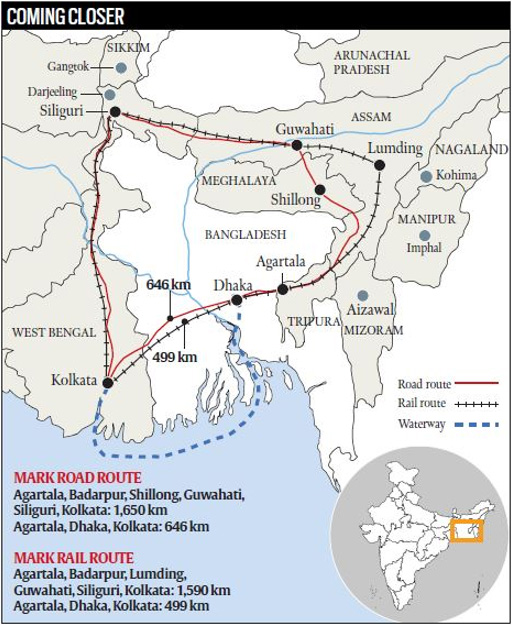

Figure II: Road and Rail Routes between India and Bangladesh

Source: “Through Bangladesh, a development shortcut”, The Indian Express, November 30, 2015 at http://indianexpress.com/article/explained/through-bangla-a-development-shortcut-for-northeast/

Source: “Through Bangladesh, a development shortcut”, The Indian Express, November 30, 2015 at http://indianexpress.com/article/explained/through-bangla-a-development-shortcut-for-northeast/

South Asia Rail Corridors:

The BBIN MVA takes the long nurtured dream of road-connectivity a significant step closer to reality. The translation of contemplated railway corridors from concept to reality, however, is still work in progress, incrementally. Of the Rail Corridors, existing or contemplated, for the SAARC region, the following are worth mentioning:

- Western sector

- Wagah-Atari (linking India and Pakistan – notably, this particular corridor was never disrupted in last over six decades, four wars notwithstanding; but this is essentially a point-to-point connection, and trains from either country do not foray further west or east beyond these two stations into each others’ railway network).

- Eastern sector

- Dhaka-Chittagong (internal to Bangladesh)

- Dhaka- Darsana- Khulna (internal to Bangladesh)

- Dhaka-Kolkata (operational between India and Bangladesh, point-to-point, as at Wagah-Atari, for several years now, but needs to be made more passenger-friendly in terms of customs and immigration procedures)

- Khulna-Kolkata, (under active consideration between Bangladesh and India)

- Agartala-Akhaura (work in progress, with Indian assistance, will link Bangladesh with Tripura State of India)

- Agartala-Ramu(requested by Agartala state, under consideration, will require a bridge over Feni River which India is willing to build)

Notably, if the points between Kolkata and Agartala route are linked, either preferably with through trains of both countries or through transferring passengers with national services at destination points, the current travel distance between these two cities will be shortened from1590 kms to 499kms.

Following the decisions announced by the Prime Ministers of Bangladesh and India in their Joint Communiqué at the conclusion of the former’s game-changing visit to India in January 2010, the two sides have cooperated on upgrading, synchronizing and operationalizing existing facilities between Rohanpur-Singabad (facilitating transit to Nepal) and at Radhikapur-Birol (that will help both Nepal and Bhutan)

Additionally, a SA-SEA rail Corridor of4,430 kms Kolkata-Ho Chi Minh City corridor is also under consideration, but remains mainly on the drawing board at present. However, daunting impediments remain to realizing this dream, mainly hugely higher costs with more extensive gaps (2,493 kms of missing links) that require to be connected over somewhat difficult terrain in places, and incompatibilities of railway track gauges between different national grids. The challenges to the entire Trans-Asian Railway project are even more daunting, with 10,500 kms missing links. Transshipment costs between regions are also costly.

Considering the diversity in the terrain in different regions and locations, perhaps the best approach would be to adopt an organic approach and configure the corridors and linkages in a manner that best appear to be in consonance with geo-morphology of different terrain. In the northeast of India and in parts of Bangladesh, for example, the foothills of the Himalayas are composed of relatively soft clay-like soil, and roads are very expensive and extremely difficult to maintain throughout the year. Unplanned construction of roads across hilly terrain, cutting hills and leaving naked the sides shaved without buttressing them, in combination with constant vibrations from heavy road traffic and increasingly frequent cloudbursts make many of the new arterial roads unusable for months. Extending existing railway links are also beset by multiple challenges, particularly where water bodies, hugely large and extensive, dominate much of the landscape. Northeast India, and Bangladesh and West Bengal, prior to the Partition (and even until the mid-sixties) were always water-linked perennially. The rivers systems had constituted the arterial system, with the railways akin to the venous system, while the roads, large and small, whether primary, secondary or tertiary, not unlike the human body’s circulatory system. We need to rethink connectivity corridors to be in synch with the diversity of the terrain that supports multi-modality of transport rather than uniformity.

Additional Augmenting Corridors

India and Bangladesh, and even Bhutan are now keen to reviving national waterways to augment national highway, in consonance with geo-morphology. Where national waterways can be linked (and the Eastern Himalayan Rivers, the Ganges and the Brahmaputra essentially are trans-national rivers), they can easily be transformed into becoming sub regional or regional waterways. Conceptually, one could then conceive of the Lower Brahmaputra Basin network linking Bhutan, Assam and Meghalaya (India) and Bangladesh, while the Ganges Basin network could act as water corridor connecting Nepal, India and Bangladesh.

Bangladesh and India have recently entered into a direct Maritime Shipping Agreement and also signed a Coastal Shipping Agreement. They could be expanded to embrace BIMSTEC countries, with Sri Lanka, Myanmar and Thailand also joining, thereby adding another dimension to the transport corridors between South Asia and Southeast Asia regions.

Air Corridors within South Asia and between South and Southeast Asia are still VERY inadequate. In the eastern sub region of SAARC, Paro in Bhutan, Kathmandu in Nepal, only Kolkata and Guwahati in West Bengal and Northeast India, and Dhaka, Chittagong and Sylhet in Bangladesh are designated International airports. Bangladesh has offered to develop Saidpur or Ishwardi as possible gateways for Bhutan and Nepal. Airlines in the region need to more seriously consider and explore a sub-regional “Hub and Spoke” concept. A major impediment to this is the narrow and extremely conservative approach of airlines: that there is not sufficient passenger traffic to justify extra connections. This begs the question: if there are no easily available connections, where will the traffic come from?

Other Corridors

Energy corridor

Ready and adequate availability of energy is the key to development. Without fuel, the engine of the state cannot run far. All South Asian countries are deficient in power supply, whether for domestic, industrial or agricultural use, and still very heavily dependent on thermal power from using coal and hydrocarbons. This, despite there being nascent capacity to generate anywhere between 70,000 mW to 100,000 mW of hydro power in Northeast India, (in addition to large capacity for generating thermal power as well), almost equal capacity of hydropower generation in Nepal, and 27000 mW in Bhutan. The latent hydropower in the northeast is largely hostage to lack of incentives for investment, since evacuation of power from that region to the Indian national grid across Indian territory is extremely limited (15000 mW at most), unless Bangladesh were to agree to offer itself as a conduit – which it has now offered, in return for power for itself. A petroleum product pipeline from Numaligarh refinery to Parbatipur is under active consideration, as is the evacuation of power from the NE to Muzzafarnagar via Bangladesh.

Indian and Bangladesh grids are now being linked in the eastern, western and northern sectors of Bangladesh that could open up vast new vista of cooperation, putting in place. The power grids of Bhutan and India are also linked, as are those of Nepal with India. These three grids could eventually be triangulated to form a sub-regional grid. Eventually, an interlinking sub-regional grid of symbiotic interdependence would emerge, that would guarantee long term energy for the sub-region, and beyond, and fuel the engines of growth and development for the peoples of this sub-region. Conceptually, with the still untapped reservoirs of power in Myanmar, the energy corridors could link the two regions dynamically in helping each other fuel their respective economies even more deeply. Were the 3-nation gas pipeline project between Myanmar, Bangladesh and India, aborted in the mid nineties, to be revived, the concept of energy corridors between SA and SEA would acquire dynamic new substance. The main challenge to converting this concept into reality for the political leaderships is to recognize the need to cooperate in their own larger national interests, to begin with, that would then enlarge and converge into shared trans-regional prosperity.

IT Corridor

In an age today where IT dominates the power of acquiring new knowledge and research, but where bandwidth shortage can be a real impediment to vaulting national ambitions, the idea of also having an IT corridors, sharing bandwidth has now also come of age. Bangladesh happens to possess more bandwidth than it can domestically consume now, by virtue of its sea cable link acquired from Singapore. So it is exporting some of it to the -NE India, with the IT gateway in Agartala connecting Tripura to Cox’s Bazaar through Akhaura. In a sense, an IT corridor has already been established by this deal between the two regions. One foresees further, steady expansion in this field as well.

Major challenges

While waxing eloquent on all these ambitious trans-regional linking soaring with visionary ambitions, one must at the same time keep one’s feet on the ground.

We must keep in mind that financing such cross-regional infrastructure projects always tend to pose major challenges, primarily being risk prone (subject to a complex mix of problems), mostly stemming from politics, whether domestic or regional being at cross-purposes. Therefore, historically, there is a tendency to great wariness resulting in financing vehicles being bearish rather than bullish. Public sector financing also tends to be increasingly constrained due to fiscal challenges to national economies. Commercial financing has also been seen to be constrained by successive global financial crises. In such shaky situation perhaps the best bet would be to take recourse to bond markets, and encouraging more public-private partnerships.

Having a large vision for the future

Improving trade & transport facilitation between the two regions would undoubtedly make trading between these regions easier and more stable, while also lowering transaction costs. But this first needs to be done more within the South Asian countries, where the infrastructure in place is abysmally inadequate and of poor quality when compared with what exists in the Southeast Asian region. Each South Asian state has a daunting challenge to cope with within its own national perimeter. What is a challenge within domestic context is MORE of a challenge in regional/sub-regional context. Therefore, it is absolutely essential that peoples, across borders in both regions must view potential gains from such cooperative linkages as being perceptively large for both regions to wish to pursue this worthwhile goal wholeheartedly.

This article was originally published in GP-ORF’s 'Emerging Trans-Regional corridors: South and Southeast Asia.

Selected References:

Anasua Basu Ray Chaudhury, Pratnashree Basu, Mihir Bhonsale, “Driving Across South Asian Borders: Motor Vehicles Agreement Between Bhutan, Bangladesh, India and Nepal”, ORF Occasional Paper # 69, September 2015.

Connecting South Asia and Southeast Asia, A joint study of ADB and ADBI, 2015.

“India, Nepal, Bhutan and Bangladesh Sign a landmark Motor Vehicles Agreement for seamless movement of road traffic among Four SAARC Countries in Thimphu”, Press Release, Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Road Transport & Highways, Government of India, 15 June, 2015.

Jean-Francois Gautrin, “Connecting South Asia to Southeast Asia: Cross-Border Infrastructure Investments”, ADBI Working Paper, No. 483, ADBI, May 2014.

Mustafizur Rahman, Khondaker Golam Moazzem, Mehruna Islam Chowdhury,

and Farzana Sehrin, “Connecting South Asia and Southeast Asia: A Bangladesh Country Study”, ADBI Working Paper, No. 500, ADBI, September 2014.

“Through Bangladesh, a development shortcut for Northeast”, The Indian Express, November 30, 2015.

Wignaraja, Morgan and Plummer, “The case for connecting South Asia and Southeast Asia”, Asia Pathways, ADBI blog, May 2015.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source: Nations Online Project at

Source: Nations Online Project at  Source: “Through Bangladesh, a development shortcut”, The Indian Express, November 30, 2015 at

Source: “Through Bangladesh, a development shortcut”, The Indian Express, November 30, 2015 at  PREV

PREV