Regional focus has turned towards the Indian Ocean as the new frontier for sustainable economic development, alongside concerns of security issues. India should build on the momentum it has created thus far and take on a larger responsibility in developing and securing the Indian Ocean by developing ideas, norms and road maps for an inclusive and collaborative ocean governance society. Developing a normative framework for doing business and harnessing the ocean’s potential in a sustainable manner is another area where India could demonstrate leadership. This framework must ensure a just and equitable environment for seizing the business opportunities in the IOR.

India should start by creating robust mechanisms for knowledge creation. For instance, diverse platforms for interaction between sectoral experts, professionals, scientists, and the business community could be envisaged. The existing and new multilateral trading agreements should also be modified and defined in a way that enables the creation of sustainable infrastructure to meet the demands of future economic activities.

About the Author

Sonali Mittra is an Associate Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi. She is also Academy Senior Fellow at Chatham House in London.

Endnotes

[i] United Nations. Blue Economy Concept Paper. (Rio de janeiro: United Nations, 2012).

[ii] Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. “Sustainable Development Goal 14”. Accessed December 2, 2016, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg14.

[iii] See: Third International Cooperation on Small Island Developing States, Samoa 2014, 21st African Union Summit 2013, Post-2015 Development Conference 2015, IOR’s Blue Economy Conference 2015.

[iv] See: Ocean Policy Statement of 2002, the Indian Maritime Agenda 2010-2015, and the latest Ensuring Secure Seas: Indian Maritime Security Strategy 2015.

[v] Centre for Coastal Zone Management and Coastal Shelter Belt. “Database on Coastal States of India”. Accessed December 2, 2016, http://iomenvis.nic.in/index2.aspx?slid=758&sublinkid=119&langid=1&mid=1.

[vi] Ibid

[vii] Planning Commission of India. Press Note on Poverty Estimates, 2011-12. (New-Delhi: Government of India, 2013).

[viii] Labour Bureau, Ministry of Labour and Employment. Report on Fifth Annual Employment-Unemployment Survey (2015-16). (Chandigarh: Government of India, 2016).

[ix] Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. Indian States by GDP. Accessed December 5, 2016, http://statisticstimes.com/economy/gdp-of-indian-states.php

[x] Planning Commission. State-wise YoY Growth Rate by Industry of Origin (2004-05 Prices). Accessed December 5, 2016, http://planningcommission.nic.in/data/datatable/data_2312/DatabookDec2014%2085.pdf

[xi] Senapati, Sibananda and Gupta, Vijaya. Climate change and coastal ecosystem in India: Issues in perspectives. (New-Delhi: International Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2014).

[xii] Mohanty, S.K et al. Prospects of Blue Economy in the Indian Ocean. (New-Delhi: Researcj ad Information System for Developing Countries). Accessed December 7, 2016, http://ris.org.in/pdf/Final_Blue_Economy_Report_2015-Website.pdf

[xiii] Oceans Policy Science Advisory Group. Marine Nation 2025: Marine Science to Support Australia’s Blue Economy. (Sydney: Government of Australia, 2013).

[xiv] Prime Minister’s Office . The Ocean Economy: A Roadmap for Mauritius. (Mauritius: Government of Mauritius, 2013).

[xv] Zhao, Rui . The Role of the Ocean Industry in the Chinese National Economy: An Input-Output Analysis, Centre for the Blue Economy.(Monterey: Monterey Institute of International Studies, 2013).

[xvi] Centre for Coastal Zone Management and Coastal Shelter Belt. “Database on Coastal States of India” Accessed December 2, 2016, http://iomenvis.nic.in/index2.aspx?slid=758&sublinkid=119&langid=1&mid=1

[xvii] Press Information Bureau. Economic Survey 2015-16: Services Sector remains the Key Driver of Economic Growth contributing almost 66.1% in 2015-16. Ministry of Finance. (New-Delhi: Government of India, 2016).

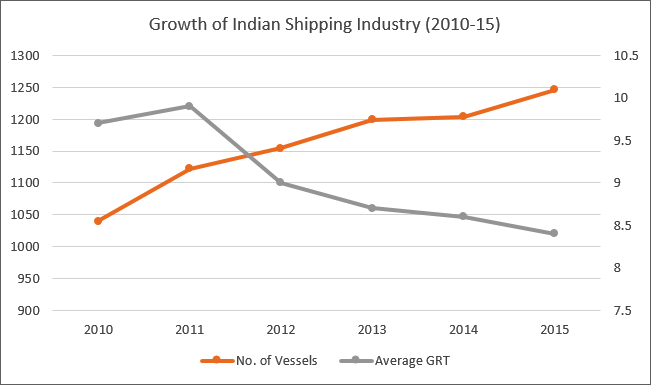

[xviii] Ministry of Shipping. Indian Maritime Agenda 2010-2020. (New-Delhi: Government of India, 2011).

[xix] Ministry of Road Transport and Highways. Indian Shipping Statistics 2015. (New-Delhi: Government of India, 2016). Accessed December 7, 2016. http://shipping.nic.in/showfile.php?lid=2280

[xx] Indian Ocean Rim Association. Mauritius Declaration on Blue Economy. Accessed December 3, 2016, http://www.iora.net/media/158070/mauritius_blue_economy_declaration.pdf

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV