-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Skill mismatch in employment remains unresolved despite past policies. The new Budget should sustain investments in manufacturing and bridging skill gaps.

Image Source: Getty

This is the second piece in a three-part series discussing India’s Budget imperatives. Read part 1 here.

As the presentation of the 2025-26 Union Budget draws close, analysts in the media are debating what the government’s new priorities should be—resulting in mass speculation. However, there is an issue which has persisted despite several reforms undertaken by the government: the problem of employment. The problem is not limited to unemployment, since according to official statistics, the country has fared well in that aspect. The economy is facing an allocation problem—a decoupling of employment and output across the sectors. This is further exacerbated by a skill-mismatch issue, making India’s employment problem largely qualitative.

The agricultural workers, with low-level skills, are usually absorbed into the industry with structural transformation.

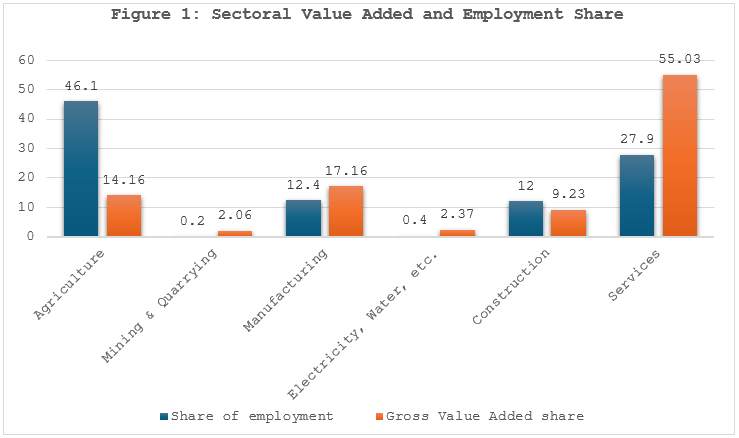

The stark divergence in employment and output across sectors, visible in Figure 1, can be partly attributed to the opening up of a premature industrial sector to the forces of international trade through the 1991 reforms. This led to the dominance of the service sector. The service sector continues to sustain growth and employment in the economy. However, constrained manufacturing growth became a bottleneck to the structural transformation of employment. The agricultural workers, with low-level skills, are usually absorbed into the industry with structural transformation. In the Indian case, the emergence of the services sector, which requires high-skilled workers, prevented this transition, resulting in the disproportionate distribution of workers and output.

Source: PLFS 2023-24, and MOSPI

While the services sector continues to grow owing to domestic momentum and international demand, infusing workers into the sector has to be prioritised in the Budget. Table 1 shows the worker-population ratio (WPR) across education levels, i.e., the proportion of the population who are in the workforce. A distinct trend appears, where the proportion of workers in the secondary and higher secondary levels are lower than in the not literate level. This indicates a structure where not literate workers might be absorbed into agriculture and add to disguised employment. However, individuals with a diploma or certification exhibit the highest WPR, corroborating the need for skilling or vocational courses that make workers job-ready.

Table 1: Worker Population Ratio according to education levels

| Highest level of education | WPR |

| Not Literate | 59.6 |

| Literate & Up to Primary | 68.5 |

| Middle | 60.7 |

| Secondary | 49.7 |

| Higher Secondary | 45.9 |

| Diploma/Certificate Course | 73.6 |

| Graduate | 57.5 |

| Post Graduate & Above | 62.2 |

| Secondary & Above | 52.1 |

| All | 58.2 |

Source: MOSPI

The government has previously taken initiatives to counter both problems through various schemes. For instance, to develop an internationally competitive industrial sector, and to limit reliance on imports, the government prioritised manufacturing through Production Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes. Further, the development of logistics hubs under PM Gati Shakti, the expansion of green energy manufacturing, including PLI schemes for solar modules and battery storage systems, and the extension of the Emergency Credit Line Guarantee Scheme (ECLGS) to micro small and medium enterprises were all attempts to bolster manufacturing growth. This should take care of the problem of low-skilled agricultural workers stuck in disguised unemployment or unproductive activities.

The government’s focus on employment was especially highlighted in the previous budget through a greater allocation towards employment schemes.

To address the second problem, the government has prioritised upskilling in previous budgets, through the PM Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY), for skilling youth to align with the demands of the services sector. The government’s focus on employment was especially highlighted in the previous budget through a greater allocation towards employment schemes. These included the Skill India initiative and the Employment-Linked Incentive (ELI) schemes. Three schemes were suggested under the ambit of ELI. Scheme A would provide a month’s worth of wages to new entrants in the formal sector, capped at INR 15,000 for people with a monthly income of up to INR 1 lakh. Scheme B would provide an incentive at a specified scale directly, both to the employee and the employer, towards their provident fund contribution in the first four years of employment. Finally, scheme C involves the government reimbursing the employers up to INR 3,000 per month for two years towards their provident fund contribution for each additional employee.

However, both issues continue to limit India’s growth problem. The manufacturing reforms, despite greater funding, faced severe roadblocks due to export competitiveness and energy costs, resulting in unrealised potential. Despite advances, bridging the skill gap in high-demand services like IT (Information Technology), healthcare and tourism remain a challenge. The skill-mismatch problem should be confronted by continuing the government’s dual approach. The manufacturing growth in labour-intensive sectors can bolster employment while training the existing workers enables them to smoothly transition into the services sector.

The intangible gap between higher levels of education and high-skill jobs can be eliminated with national schemes that identify the gap and augment skilled labour.

The problems can be mitigated through continued spending on education, Skill India, and the establishment of new schemes which impart training to already high-skilled workers. The intangible gap between higher levels of education and high-skill jobs can be eliminated with national schemes that identify the gap and augment skilled labour. The 2025-26 Budget should also enforce a continued focus on industrial growth. The unproductive labour should be brought into the ambit of formal enterprises, boosting domestic productivity.

To achieve the goal of Viksit Bharat, i.e., reaching high-income levels by 2047, a much higher rate of growth is needed than what is prevailing. This will require higher output over the long run, which can be attained through higher productivity. While a lower fiscal deficit can enable investment flows into the country, the government should not shy away from allocating greater capital expenditure to industry. The government must tread the line between a high deficit and lower employment. The allocations in this Budget will be a crucial juncture, which can potentially set the stage for Viksit Bharat.

Arya Roy Bardhan is a Research Assistant with the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy at the Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Arya Roy Bardhan is a Research Assistant at the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy, Observer Research Foundation. His research interests lie in the fields of ...

Read More +