Introduction

In early 2021, Russia began its two-year turn with the rotating chairmanship of the Arctic Council, taking over from Iceland.[a] The member states announced the agenda for the coming years: sustainable development, environment, and indigenous populations. Even as the Council continues its collaborative work, the Arctic region faces both enduring and new challenges brought about by climate change, new connectivity routes, the activities of non-Arctic powers, and security issues that are no longer merely theoretical.

Russia has the longest Arctic coastline among all the region’s states. The region’s contribution to Russia’s GDP is pegged between 12 to 15 percent, and accounts for almost 20 percent of the country’s exports, including 80 percent of Russian gas and 17 percent of its oil.[1],[2] The changing security situation and the resultant impact on regional geopolitics also make the Arctic vital for Moscow. Russia, which sees the melting ice as an opportunity for its natural resource-dominated economy, is quite clearly the leader in building capacity and infrastructure in the Arctic.[b] As climate change worsens, however, it is becoming clear that the melting ice will be as much a challenge for Russia as it is an opportunity.

Figure 1: Map of the Arctic

Source: Peter Hermes Furian, 123RF[3]

Source: Peter Hermes Furian, 123RF[3]

Russia’s Arctic policy, released in 2020 and covering the years up to 2035, defines its “primary national interests” as follows:[4]

- a) ensuring the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the Russian Federation; b) preserving the Arctic as a territory of peace, stability, and mutually beneficial partnership; c) increasing the quality of life and well-being of the population of the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation; d) developing the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation as a strategic resource base, and its sustainable use to accelerate the economic growth of the Russian Federation; e) developing the Northern Sea Route as the Russian Federation’s competitive national transportation passage in the world market; f) protecting the environment in the Arctic, preserving the native lands and traditional way of life of indigenous peoples residing in the Arctic zone of the Russian Federation.

Indeed, the Arctic is hardly a region that can be seen solely through the prism of domestic developments. There are multiple stakeholders involved, and this is seen in Russia’s policy document that lists challenges of an international nature (e.g., unsettled legal delimitation of Arctic areas, military build-up, and obstruction of economic activities by foreign states.) Russia has also expanded on its vision for the Arctic through a series of official documents. Such attention is not surprising, given that Russia is a pre-eminent power in the Arctic and its actions will have wide-ranging consequences for the future of the High North.

Meanwhile, as the natural ice barrier melts, other coastal states are also looking to enact new policies that could raise the prospects of an emerging security dilemma. As stakeholders’ interests heighten, many factors will likely affect the regional economic and strategic future of the Arctic: climate change, the race to exploit the region’s resources, and the opening up of new maritime routes. This paper examines these issues in the context of Russia’s ambitions in the region, and ponders whether the future of the Arctic will be ruled by competition or cooperation.

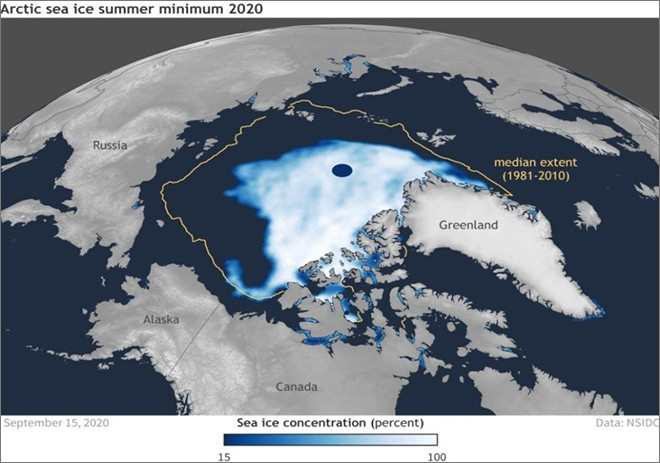

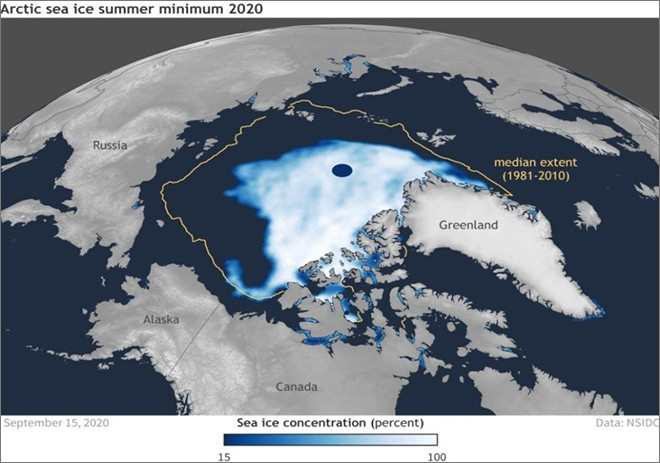

Climate Change, Resource Extraction, and Green Energy

Experts have been sounding the alarm on the impact of climate change on the Arctic for some years now. It was in 2007 when scientists announced that the region was witnessing the largest ice-loss in human history, marking a pattern of extreme climate change in the high north; today the region is warming at a rate three times the rest of the world. According to the latest UN Climate Panel report, the most optimistic scenario would still see the summer time sea ice in the Arctic vanish entirely at least once by 2050.[5] At present, the sea ice levels have been at their lowest in summer months in a thousand years.

This melting ice has opened new opportunities for the exploration of natural resources in areas that were previously frozen throughout the year,[c],[6] while easing maritime routes to transport these resources. Russia is among those countries extracting resources from the region. It is continuing with its exploration activities despite technological limitations and the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on investment capacity.[7] The Arctic is key to Russia’s aims to gain a 20-percent share in global LNG market by 2035.[8] Yet, it considers the remote region’s socio-economic development as much an economic argument as a security one. In its strategy for the Arctic till 2035, it lists the following main threats to national security, which are directly related to economic development: population decline in the Arctic zone; insufficient social infrastructure; slow exploration of mineral resource fields; lack of state support for local businesses; failure to meet development targets for the Northern Sea Route (NSR); and an inability to respond to environmental challenges.

The Arctic’s resources play an important role in Russian efforts to increase its exports eastwards to Asia-Pacific.[d] The opening up of the NSR for longer durations of the year due to global warming facilitates this plan. The Arctic has significant natural gas reserves, with newer fields like Yamal LNG expected to contribute the bulk of exports in the coming years. Analysts remain bullish on LNG because its use generates almost 50-percent less carbon dioxide than coal and 30-percent less than oil. It will help countries cut down their carbon emissions and shift to other sources of clean energy.

However, the LNG scenario is not an opportunity that can be replicated across fossil fuels like coal and oil—energy sources that countries are seeking to reduce to meet their green energy goals. Indeed, the peak oil range is estimated to have already been reached, if not by 2030.[9] Russian estimates themselves point to declining production after 2019, with offshore production in the Arctic being considered less profitable due to “low oil prices and lack of technology.”[10] This is especially relevant in the case of Europe, which constitutes a significant part of Russian energy exports, and has set an aim to decarbonise by 2050. Earlier this year, EU climate chief Frans Timmermans noted that “there will be no more space for coal, very little room for oil, and only a marginal role for fossil gas.”[11]

Russia is not unaware of the challenges. Finance Minister Anton Siluanov has warned that the country must prepare for revenue losses as certain customers transition to renewable energy.[12] The proposed carbon border tax in the EU is expected to affect about 40 percent of Russian exports. There is also an ongoing debate regarding the viability of large-scale investment into Arctic oil extraction.[e],[13],[14] Moscow is banking on the Asian market to absorb its Arctic production, as it attempts to profit as long as it can from its hydrocarbon reserves, especially in the case of oil, before the revenues start to decline.[f],[15]

Meanwhile, the surrounding regions are witnessing the negative consequences of rising temperatures: altered ocean currents, more intense heat waves and more extreme winters, rising sea levels, harm to wildlife, reduced crop yields, and unstable monsoon patterns in Asia.[16],[17]Methane that is released into the atmosphere due to the melting permafrost, will also further hasten climate change. Russia is already dealing with intense heat waves in its coldest regions leading to increased instances of wildfires that threaten human habitation and economic activity. Melting permafrost is also making infrastructure unstable.[g]

Furthermore, climate change raises questions related to food, water, and health security; and increased human activity increases the environmental risks.[18] Russia can no longer ignore the negative impacts of climate change on its population and would need to fulfil Paris Agreement goals of cutting down carbon emissions. The imperative is a longer-term approach in the Arctic—one that is concerned not only with hydrocarbon extraction but also on creating an economy that is sustainable, green, and in the longer term, focused on high-technology – necessitating closer engagement with both the west and the east.

State Borders and Military Activity

Rising temperatures have given the Arctic littoral states new security challenges as scientists warn that the region will be “ice-free” during summer by the 2040s. As previously frozen border areas are exposed, defence-related activities will likely increase in the region. Russia, as the state with the longest Arctic coastline, is deeply concerned about the implications on its national security. In its 2035 strategy, Russia has included among its challenges, the “military build-up by foreign states in the Arctic and an increase of the potential for conflict in the region.”[h] The same document says its aim is to ensure the country’s military security, and guard and defend the state border.[19] The naval doctrine, meanwhile, talks about building dual-use infrastructure in remote areas of Arctic and the Far East.

In the post-Soviet period, a revival of Russian military activities in the region is traced to 2007-08, when President Dmitri Medvedev approved the Foundations of Russia’s Arctic policy in 2008.[20] This period also saw a return of long-range bomber patrols in the Arctic for the first time since 1991, as well as regular naval patrols. The region is critical for maintaining Russia’s nuclear deterrent and preserving its “Arctic-based second-strike nuclear capability” in the Kola Peninsula that houses the ballistic missile submarine fleet.[21],[22] Towards this end, the Northern Command was created in 2014, and the Northern Fleet was “repurposed” to deal with the demands of the melting Arctic. From there, the Russian naval forces project power and maintain access to the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

Analysts note that it was in the 2014 military doctrine when Russia included, for the first time, the protection of national interests in the Arctic as one of the main tasks of the armed forces, although defensive in nature.[23],[24] The 2015 maritime doctrine too, lists the aims thus: to ensure national defence, border security, and safety of EEZs and the NSR. Some scholars have noted that in more recent documents, there is a trend towards “sovereignty-oriented and nationalistic language.”[25] For example, the 2017 Fundamentals of the State Policy in the Field of Naval Operations sees the US ambitions in the region as a threat to its security. The 2020 Basics of the State Policy in the Arctic, for its part, includes as a key goal, “protection of sovereignty and territorial integrity.” Meanwhile, the 2021 national security strategy–in a departure from its 2015 version–accuses some states of using climate change and other environmental issues to hinder “Russia’s development of the Arctic.” Throughout these policy documents, the goal of Russian foreign policy remains to “ensure interests of the Russian Federation” in the region.

Russia has invested in new infrastructure, better equipment, advanced research, and regular training to bolster its defence.[i] It has reopened several of its Cold War-era bases and airfields.[26],[27] As economic activity gathers pace in the region and with a view towards ensuring security of shipping along the NSR, Russia has created two new coastal defence divisions and is strengthening the Border Guard Service to carry out border control and secure oil and gas fields.[28] While Russia believes that an increase in these activities is essential to defend its long Arctic border that is no longer protected by impenetrable ice, some states have labelled its actions as “aggressive”.

Figure 2: Arctic sea ice summer minimum (2020)

Source: World Meteorological Organization[29]

Analysts say the growing offensive capabilities of Russia are a challenge to the US: hypersonic cruise missiles and precision-strike munitions, unmanned underwater vehicles, and modernised naval presence.[30] This is relevant given the current state of Russia-US ties, as well as the fact that five of the eight Arctic Council permanent members are NATO allies—i.e., Canada, Denmark, Iceland, Norway, and the US. Sweden and Finland remain close partners of the US and other western states. The suspension of the meeting of heads of armed forces of the Arctic States after the 2014 Ukraine crisis has also closed down a venue for regular communication on military issues. Given that the Arctic Council does not address security issues in any form, there is currently no format for discussing this critical aspect of the emerging situation in the region, post-2014. There has also been a steady rise in the number of military exercises by Russia. Training activities increased by 15 percent between 2014 and 2015, reflecting the forces’ heightened preparedness.[31]

Russia analysts are of different views on the country leading the ice-breaker fleet with 40 vessels, which it is augmenting by at least a dozen by 2035; many of these will be nuclear-powered.[32] While observers reckon that Russia is building this fleet to ensure year-round navigation across the NSR, it does have a dual-purpose.

The US has only two icebreakers at present, which are not enough to meet all the needs of shipping traffic channels, necessary for defence/security reasons, Arctic drilling, and research.[33] The US ships are not “ice-hardened”, which is another crucial limitation in the high north. Military analysts point out that US weaknesses regarding ice-class vessels/ice-breakers do not necessarily translate to a huge military disadvantage. After all, the main challenge arises not from a higher number of icebreakers but from an enhanced Russian missile, air, and surveillance capacities.[34]

These moves by Russia, when combined with other actions like increased naval, submarine and air patrols, can be interpreted as “provocative”. They could be used offensively,[35] and worsen mutual distrust. Finland and Sweden, for instance, have complained about Russia’s air patrols, and other states like Norway are concerned about Russia’s Radio-Electronic Shield deployed in 2019 to cover the Arctic. This technology enables the jamming of satellite communications, GPS signals and drone communication of foreign aircraft and ships.[36] The newly tested hypersonic missile, which supposedly evades any existing missile defence system, extends the range of Russian forces right to the US borders and has been a cause of concern as well. Indeed, Russia remains the pre-eminent military power in the Arctic, with significant advances in its capacities in the 21st century.[37]

Some scholars note that the overall Russian policy here is not too different from those of other Arctic states like the US and Canada; though they agree that post-2014, Russia’s threat perception from the west, even in the Arctic, has heightened.[38] To be sure, Russian activity today remains “significantly lower” compared to the Cold War period, but its pace and scale has led to a response from other states.[39] The United States, apart from updating its Arctic strategies and equipping its forces in the region especially in Alaska, has engaged its NATO allies and partners in the region for power projection.[j],[40] The US navy has also been conducting patrols in Barents Sea.[41] These moves, coming in response to each other’s defence activities, could create a security dilemma. For now, however, the militarisation of Arctic remains largely manageable and military experts have cautioned against overstating it.

Even NATO still does not have a distinct Arctic policy. Russia continues to maintain the posture of a “status-quo power” and has been “transparent” about its intentions.[42],[43]Various analysts agree that most of Moscow’s activities are designed for close-in perimeter defence and protection of borders. The focus is on “soft” security issues, including protection of economic resources, preventing illegal activities, and patrolling.[44] This is in recognition that a conflict-ridden Arctic will prove detrimental to its developmental plans in the high north. Even for the US, the focus remains on the Western Pacific and South China Sea, and experts say it is unclear the extent to which there will be a revision in its understanding of the Arctic as “an area of geopolitical tension.”[45] The coastal states are not involved in bilateral disputes that could lead to conflict; they follow established rules and focus on the security of the region.[46]

While the overall risk of conflict is still assessed to be low, and military activity is far from reaching the highs of the Cold War period, there is an active need for diplomacy to ensure it stays that way. The regional states have demonstrated a desire to avoid moves that could destabilise the region, and this restraint needs to be maintained. Avenues for discussions on hard security issues have been closed, as annual meetings of the Chiefs of the Armed Forces of Arctic states were suspended after the Ukraine crisis, and Russia has been disinvited from the Arctic Security Forces Roundtable. This creates risks and uncertainties that could be dangerous in the long run, necessitating a solution that creates conditions for contacts between the militaries.[47]

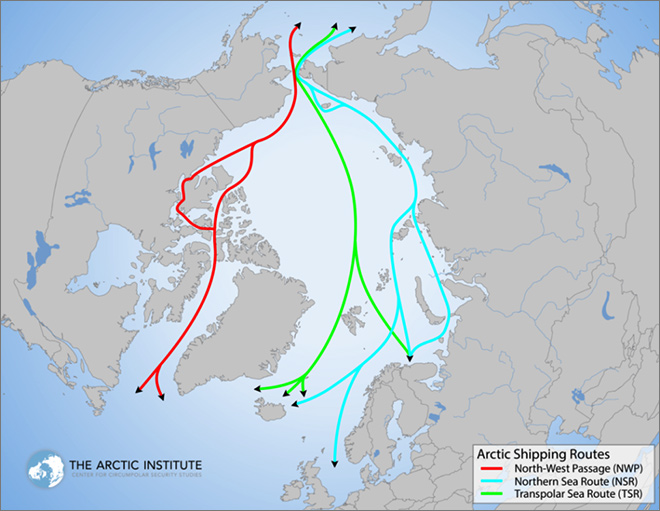

Connectivity via NSR

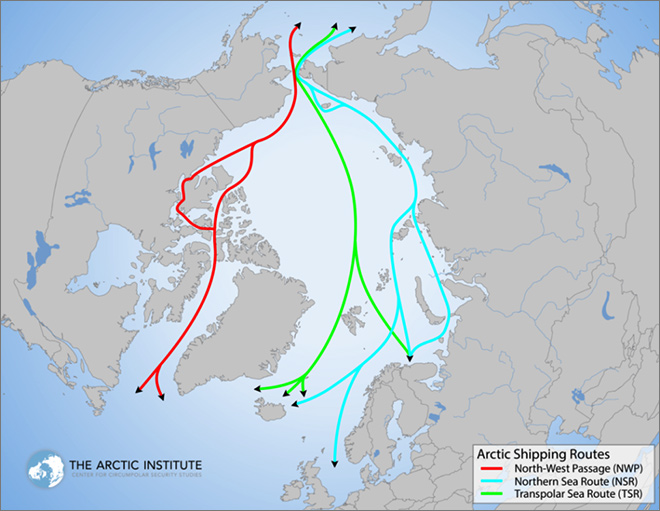

One of the most visible impacts of melting Arctic ice has been on connectivity routes along the Arctic, of which the NSR is a part. The route cuts down the time needed by ships to navigate between Europe and Northeast Asia by 40 percent (or about 14 days).[48] As Russia invests in oil and gas fields in the Arctic, the role of NSR in transporting the resources both westwards and eastwards has become more significant. This has also resulted in President Vladimir Putin making the declaration that his country will increase transit to 80 million tonnes by 2024 (from 32 million tonnes in 2020); this has been described as ambitious given the current volumes.[49] The eastward link of NSR to Asia is currently navigable for only six months of the year, and Russia has embarked on expanding its ice-breaker fleet to enable year-round navigation along the route by 2025—a process that is expected to be aided by the longer ice-free periods in the Arctic because of global warming.

In 2018, the State Atomic Energy Corporation, Rosatom, was tasked to develop the NSR infrastructure and ensure its sustainable functioning. These include plans for expanding the ice-breaker fleet, improving search and rescue, communications, port infrastructure, constructing airports, building railways lines, and weather prediction.[50] The Russian strategy for the Arctic up to 2035 lists the development of the route as a “competitive national transportation passage in the world market” as a primary national interest in the region.

In 2020, 32 million tonnes of cargo were transported via the NSR, with Novy Port (crude oil) and Yamal LNG contributing 80 percent of the total volume.[51] Apart from energy resources, Rosatom believes coal will play a role in helping Russia achieve higher volumes on the route, apart from Arctic LNG 2, Vankor oil and Payakha field.[52] This refers almost exclusively to destination shipping, with low transit shipping being attributed to causes such as that usually container ships load and unload in several ports along their route, with timetables produced months in advance to ensure delivery of goods at the exact time.[53]

Figure 3: Arctic Shipping Routes

Source: Malte Humpert[54]

Other factors include high costs of ice-breaking, higher insurance cost, lack of ice-class vessels that require higher investment, as well as higher fuel costs. The NSR is therefore unlikely to replace other maritime connectivity routes anytime soon. By 2035, Russia’s own estimates of transit shipping remain limited at three million tonnes,[55] with the expectation that this would become attractive in the long run through establishment of adequate infrastructure, availability of ice-class vessels,[56] as well as development of shuttle transportation between Murmansk and Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky.[57]

Short- to medium-term estimates do not suggest a steep rise in transit traffic. Russia thus seems to be intent on inward-looking policies for the Arctic that focus less on the international use of the route.[58] This has coincided with Russia’s deteriorating relations with the West. Russia’s priorities are on developing its internal resources, resulting in the passing of laws that limit the activities of foreign vessels on the NSR, including in transporting natural resources, cabotage, and transportation.[59],[60]

International Law

The Northern Sea Route is composed of waters of different status, including the “internal, territorial, and adjacent waters, EEZ, and the open sea.”[61] This is reflected in the definition of the route as per Article 5.1 of the Russian Merchant Shipping Code.[k] It considers the entire NSR as a single transportation route where a “single legal regime of navigation” applies.[l],[62] Russia’s laws on the navigation of foreign vessels via NSR are based on its historical claims, its inability to divide NSR into sections with different legal positions, as well as the Article 234 of UNCLOS that deals with ice-covered regions.[63]

Article 234 of UNCLOS is fundamental to Russia’s sovereign claim over the NSR:

Coastal States have the right to adopt and enforce non-discriminatory laws and regulations for the prevention, reduction and control of marine pollution from vessels in ice-covered areas within the limits of the exclusive economic zone, where particularly severe climatic conditions and the presence of ice covering such areas for most of the year create obstructions or exceptional hazards to navigation, and pollution of the marine environment could cause major harm to or irreversible disturbance of the ecological balance. Such laws and regulations shall have due regard to navigation and the protection and preservation of the marine environment based on the best available scientific evidence.

Russia backs its position on NSR with this exclusive provision regarding ice-covered areas, which gives coastal states the additional rights regarding marine pollution in its EEZ. As the ice melts, it will endanger NSR’s status as per Article 234.[m] Russia is therefore calling for an “expanded interpretation of the article” that will stress the ecological argument.[64]

With regard to navigation in the NSR, the 2013 rules enacted by Russia simplified the procedures on icebreaker assistance, ice pilotage, and the fees to be paid. However, in the aftermath of the 2014 events, there has been a shift in Russian law-making efforts on the NSR. The 2017 Federal Law No. 460-FZ that amends the Russian Merchant Shipping Code made it mandatory for ice-breaking services and pilotage assistance in the NSR to be performed by vessels sailing under the Russian flag. In addition, Moscow has ruled that all oil, natural gas, gas condensate and coal produced in Russia and loaded onto vessels located in the Northern Sea Route area must be carried by vessels sailing under the State Flag of the Russian Federation until the first point of unloading.[65], The rules were further amended to include a provision that only Russian built vessels would be allowed to transport extracted resources, although there could be exceptions.[n],[66]

These new rules are expected to still limit the use of the route by foreign vessels and their interest in using the NSR.[67] Already, sanctions have limited the role of western companies in ongoing Russian projects in the Arctic, significantly reducing their activities in the NSR. The new domestic laws have also brought Russia in dispute with the US, which insists that the Arctic maritime routes are part of the global commons.[68] Incidentally, this American position brings it in opposition to its ally Canada, which takes a position similar to Russia’s regarding the Northwest Passage. The US and some other countries have called the icebreaker and pilotage rules “discriminatory”.[69]

While the US has insisted on freedom of navigation, its ability to conduct FONOPs remains limited by its ice-breaking capacity and ice-class ships. There is also the fact that any FONOP in NSR would strain relations with Canada, which would feel threatened over its claims in the Northwest Passage.[70] Also, Russia has strong military capacities in the NSR, which is considered a national security issue, and its economic stakes make it sensitive to any actions deemed as hostile. In contrast, the US does not have vital interests in the NSR, and neither is the route a critical international transit link.[71] However, concerns remain about whether Russia will use force to deny access and enforce its interpretation of the right to free passage along the NSR.[72] A recent notification calls for foreign warships to give a 45-day notice before passing through the route. This has not yet entered into force. Although the 45-day rule is not applicable to commercial traffic, it has been negatively perceived by other stakeholders.[73] Broadly, the rules around the NSR have strengthened state control over the route, but its legal status is still being debated, and domestic and international laws are yet to be harmonised.[74]

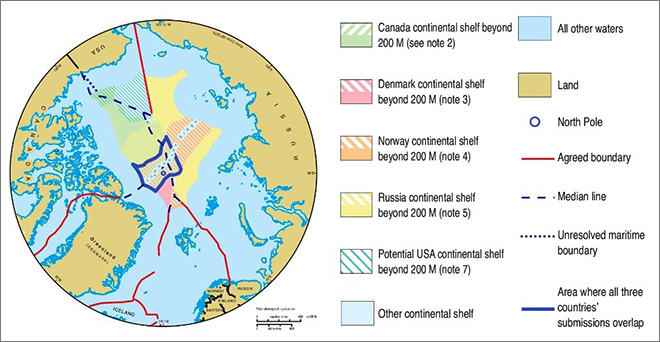

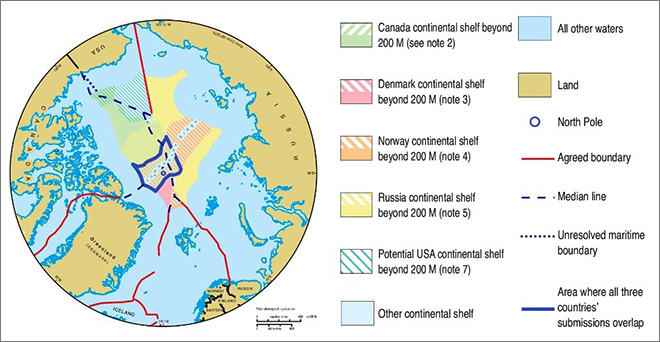

Another legal issue that Russia is involved in is being heard by the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS). This relates to the determination of the outer limits of the Russian continental shelf, as stipulated by the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).[o] Russia filed a claim in 2007 arguing that the 1800-km-long Lomonosov Ridge and Mendeleev Ridge are an extension of Russia’s continental shelf; if it succeeds, it will gain access to the vast natural resources in that area as well.[75] The same area is being claimed by Canada and Denmark. Russia was asked to resubmit its claim, which it did in 2015, though a decision on the issue is not expected soon due to the number of issues pending before the commission. The decision regarding any extension is made through scientific research to determine its geological validity. All the parties in this case have agreed to approach the issue through established legal mechanisms and are not demonstrating any intent to disregard the provisions of international law. This desire to maintain cooperation, experts argue, is also due to the desire of Arctic states to keep other countries out of the region.[76] This was witnessed in 2018, when despite ongoing tensions, Russia and the US agreed on the rules of passage for Bering Straits.

Broadly, Arctic states adhere to international law in case of any disputes and seek to address any claims through negotiations. The Russian foreign policy concept of 2016 recognises the importance of cooperation among regional players for sustainable development of natural resources and argues that existing international law is sufficient to settle any regional issues through negotiation.[77] Here, UNCLOS plays an important role, and despite the differences over maritime routes, there have been no reports of aggressive actions by any party in these areas.

Figure 4: Continental shelf submissions in the Arctic Ocean

Source: Durham University[78]

Cooperation vs. Tensions

The events and developments discussed in earlier sections of this paper collectively have an impact on geopolitics in the Arctic. The Arctic Council, since its formation in 1996, remains the key organisation for shoring up cooperation among the member states. Earlier, in 1993, Russia lent its support to the formation of Barents Euro-Arctic Council which transformed an area of Cold war strains into one of cooperation.[p] Over the years, the Council has succeeded in producing three legally binding agreements among the Arctic states: search and rescue, oil spill prevention, and scientific cooperation. The Arctic Coast Guard Forum and the Arctic Economic Council have also been established to facilitate coordination among member states on issues of common concern. Its mandate does not extend to security issues, however.

In the latest foreign ministers meeting of the Council in May 2021, where Russia took over as chair for 2021-23, the agenda focused on sustainable development, indigenous peoples, environment protection and climate change, and socio-economic development. For the first time ever at this meeting in Reykjavik, the Council adopted a Strategic Plan from 2021-2030, envisioning the Arctic as “a region of peace, stability and constructive cooperation.”[79] All the Arctic states are wary of outside players staking any claim in the region and its resources, and believe that maintaining a cooperative stance will help all the parties preserve their respective economic and political interests.[80] Whether it is the Norway-Russia agreement over their Barents Sea border in 2010 or the US-Russia decision over Bering Straits in 2018 at the height of their bilateral tensions, parties have historically engaged in negotiations to resolve contentious issues.[q] As noted earlier, they have also demonstrated a commitment to following the provisions of international law that apply in the area.

This behaviour is aided by the fact that most natural resources are located within the EEZs of respective countries, which are undisputed—this reduces the risk for active conflict.[81] This has also meant that any talk of “scramble for the Arctic” is largely alarmist.[82] Some disputes exist between NATO allies in the Arctic, such as the US and Canada over the Beaufort Sea border, Hans Island, and Northwest Passage. While this shows that even allies can have divergent interests in the high north, the issues have been handled pragmatically with a focus on maintaining cordial ties.[83] Russia’s Arctic policy continues to aim for a peaceful, cooperative region; a position that is not at odds with other regional states.

This is not to deny undercurrents of geopolitical competition in the Arctic, which is now seeing a resurgence after a lull driven by the collapse of the Soviet Union. Heightened activity around Russian military infrastructure, China’s announcement of its White Paper on the Arctic declaring itself a “near-Arctic state”, the state of US-Russia and US-China relations – all together have trained the spotlight on the Arctic. Moscow has its concerns about the US and its allies coming together near its borders in the Arctic.

As a state that does not share a coastal border with the Arctic, China’s attempts to expand its influence have been limited.[84] It has focused on geoeconomics to increase its regional presence–including making investments in Russian Arctic’s LNG projects as well as in Greenland, 5G partnerships with Icelandic companies, and scientific research. China has built two icebreakers and is working on building a nuclear-powered one, with the potential for dual-use. Beijing is aware that maritime connectivity between Europe and Asia via the high North can reduce its Malacca Straits dilemma and give it access to crucial resources while saving time and costs for the transport of goods. Western sanctions on Russia have also led to greater interaction with China in the region, both as a consumer of resources and as an investor. Indeed, the US ‘Strategic Blueprint for the Arctic’ clubs the two countries together, arguing that regional peace and prosperity will increasingly be challenged by Russia and China.[85]

However, the growing closeness between Russia and China does not necessarily translate into a partnership in the Arctic. Unlike the US and Russia, China is not geographically located in the Arctic, but has announced the Polar Silk Road as part of its flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).[r] Contrary to China’s proclamation of itself as a “near-Arctic” state, [86] Russia insists on the primacy of the coastal Arctic Five. As a non-Arctic state, Beijing has not been able to claim a role in the governance of the region but sees itself a stakeholder that must be involved in shaping the Arctic agenda.[87] However, Russia has not been willing to allow non-Arctic states, including China, to take an upper hand in either economic or security domains. The imposition of western sanctions on Russia, which limited the activities of its companies in oil and gas exploration projects, has paved the way for Chinese investment into Arctic projects like Yamal LNG and Arctic LNG 2. However, Russia has been careful in maintaining a diversified portfolio of investors and retaining the controlling stake.[s],[88]

Russia’s and China’s positions on Arctic issues have also diverged over the years. This is evident in the case of NSR, where China is wary of developing the route alongside Russia, lest it signal support for the latter’s domestic control over the connectivity link.[89] While Moscow treats the NSR as part of its territorial waters where Russian rules apply, the Chinese white paper calls for the application of UNCLOS and “general international law”, and that freedom of navigation be observed on all shipping routes in the Arctic.[90] Just as China cites UNCLOS to call for freedom of navigation, Russia too, relies on the international treaty to make its case for regulating navigation and claiming sovereignty over NSR rulemaking. It focuses on the exception provided to ice-covered areas under Article 234 for its claims, placing it at odds with China. Interestingly, China diverges from its own assessment of freedom of navigation in the case of South China Sea. It uses the argument of “exceptionalism and historical argument” to make its case within the nine-dash line but is reluctant to allow the same argument to hold in the case of the NSR.[t],[91],[92]

Moreover, Chinese shipping companies are also biding their time to ascertain the profitability of the route, with only COSCO operating in the NSR. Russia and China have also not shown signs of any joint policy on the Arctic. Indeed, as mentioned briefly earlier, they have different interests in the region and their perspectives on Arctic developments and governance could point to disagreement in spite of cooperation on specific projects.[93]

Overall, analysts are of the view that Russian behaviour in the Arctic reflects its desire to be a “status-quo power”.[94] China has signalled enhanced ambitions through the release of its 2018 White Paper. For now, it is expanding its influence by building bilateral relations with Arctic states, through its position as an observer in the Arctic Council and building its infrastructure capacities in the region.

The US, meanwhile, is experiencing a decline in its presence in the region, primarily on account of lack of ice-class vessels and outdated icebreakers. Moreover, it accords less economic importance to the region. This is because it is not looking to Alaska to meet its energy needs, and a sale of oil leases in the coastal plains of Alaska did not lead to any major interest from energy companies who are instead focused on renewable energy.[95] The lack of infrastructure, coupled with environmental concerns, has limited its activity in Arctic hydrocarbon extraction.

However, the US remains interested in the region alongside its NATO allies and partners, and has revived its Arctic policy in the past years through publication of new strategies by the Department of Defence, the Navy, Air Force and the Coast Guard. Also, it exercises influence through its partners (Finland, Sweden) and NATO allies (Canada, Denmark, Iceland, Norway) among the Arctic eight.

India in the Arctic: An Overview

- India signed the Svalbard Treaty in 1920.

- Its research program in the Arctic began in 2007, and became an observer state in the Arctic Council in 2013.

- In 2018, India received its first shipment from Yamal LNG in the Arctic.

- Impact of changing Arctic on monsoon patterns in India, and its impact on weather conditions and rising sea waters.

- Draft Arctic policy circulated in January 2021 for public response that included five pillars: science and research activities, economic and human development cooperation, transportation and connectivity, governance and international cooperation, and national capacity building.

- While New Delhi is still to notify its official Arctic policy, the January 2021 draft version as noted earlier seeks to play a constructive role through scientific research, climate studies and sustainable harnessing of resources.[96] It also expresses an interest to invest in regional infrastructure and digital economy, while also contributing to the efforts of the Arctic Council.

- India is interested in connectivity routes opening up, investment in Russian oil and gas sector, mineral resources, scientific research. It is concerned about the impact of melting polar ice caps on monsoon patterns in South Asia, besides other extreme weather phenomena.

- However, despite coming at a time of evolving regional order in the Arctic, the draft policy did not focus on geopolitical developments in the Arctic.

- In terms of bilateral interactions with Russia, a peaceful region would facilitate India’s forays into different energy and infrastructure projects, further facilitating its engagement with both the Russian Far East and the Arctic as part of the India-Russia bilateral partnership. If India plans to increase resource imports via the Chennai-Vladivostok maritime corridor, then security in the Arctic would be an important consideration.

- New Delhi also has cordial relations with other Arctic states, and must build on these partnerships to preserve its positive engagement with the region. A key step in that direction would be unveiling its Arctic policy that sets the agenda, aims, and boundaries of Indian presence in the high north for the short to medium term.

|

Conclusion

Russia’s manoeuvres in the Arctic region emerge from a finely balanced policy that has elements of both cooperation and competition. It has a large economic stake in the region and seeks to maximise gains from resource extraction. The Arctic is crucial for its national security and its projection as a great power. Moscow needs foreign investment to realise its ambitions.

Meanwhile, the Arctic States have not demonstrated willingness to engage in direct conflict in the region, and want to maintain their primacy. This common interest has meant that despite the rising tensions between Russia and the West, its negative impact on the Arctic has been largely absent.[97] The work of the Arctic Council continues with a focus on cooperation on issues related to sustainable development, climate change, conservation, emergency response, and marine environment protection.

All stakeholders are adopting a responsible approach towards problem solving in the Arctic. At the same time, increasing militarisation and opening up of new maritime routes, as well as rising interest from China, has the potential to heighten uncertainty in the region. The debate around Russia’s new rules regarding navigation in the Northern Sea Route, as well as its legal status, can also be a source of friction in the future. Greater clarity will be needed when international transits increase on the route in the future.[98]

While there are reservations in the West regarding re-starting the security dialogue mechanism on Arctic with Russia, lest it be construed as a weakening of its post-Ukraine position, the prevailing situation demands that alternative modes of communication be established not only to further regional stability, but also to deal with the potential fallout of a rising power like China seeking to enhance its influence in the high north.

Russia as a leading Arctic power will have to be transparent about its intentions and future plans. This will be a crucial signal for all stakeholders with the potential impact extending across regional military and non-military dynamics.[99] This will also help maintain regional peace and attract the foreign investment needed to fulfil development plans around the Arctic.

The absence of active disputes, adherence to established collaborative practices in the Arctic Council, and a desire to maintain stability among key actors has meant that the probability of conflict remains low at present. However, this does not mean that the states can afford to take the idea of ‘Arctic exceptionalism’ for granted. If the rising concerns over increased militarisation are not addressed, it could have unintended consequences for the region and lead to the deterioration of relations among the key stakeholders.

About the Author

Nivedita Kapoor is a Post-Doctoral Fellow at the International Laboratory on World Order Studies and the New Regionalism, Faculty of World Economy and International Affairs, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Russia.

Endnotes

[a]The Arctic Council, established in 1996 to promote cooperation among Arctic states, has as its members the US, Russia, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Iceland, Canada and Denmark (Greenland). Apart from these, six indigenous groups are also participants in the forum.

[b]The Arctic sea ice has been shrinking at an alarming rate due to the impact of climate change. NASA says its research reveals that the sea ice is reducing at a rate of 13 percent per decade. Without sea-ice to reflect sunlight back to the atmosphere, it is being absorbed and contributing to further warming. The Arctic is crucial to global weather patterns and the changes underway will have global repercussions.

[c]Russia estimates that oil reserves in the Arctic amount to 7.3 billion tonnes, condensate at 2.7 billion tonnes, and natural gas about 55 trillion cubic meters. Apart from energy resources, it is also rich in diamonds, rare metals, and seafood.

[d]According to the Energy Strategy till 2035, it aims to send 32% of crude, and 31% of gas produced to Asia-Pacific, including via the oil and gas fields being developed in the Arctic.

[e] Some scholars are questioning the viability of large-scale investment into Arctic oil extraction (where the largest Arctic oil terminal in the form of Vostok oil is being built). They point to factors such as expected decline in crude consumption levels, economic slowdown, high production costs, and the need for developing advanced technology in developing offshore fields. Others say each Arctic project needs to be evaluated on its own merits due to the wide differences in cost of production as a result of varying geological conditions and availability of infrastructure; and not just oil price and technology.

[f] China currently remains the major importer of Russian oil and gas in Asia, but with its aim to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 as well, the market for oil will eventually decline. Russia’s share of oil exports to Japan declined from 9% in 2015 to 5% in 2019 attributed to factors including a declining population, higher energy efficiency and switch to electric vehicles. In the case of South Korea, Russia’s share has remained unchanged from 2015 to 2019, at 6%. Russia’s outreach to Southeast Asian and Indian markets for Arctic oil supplies remains in a nascent stage at present, but these remain potential important markets for the future.

[g]The issue was brought into international prominence after an oil spill from a Norilsk Nickel storage tank leaked into rivers and other water bodies in the Arctic, caused by the melting permafrost weakening its base.

[h]Its main objectives include preventing use of military force against Russia, increasing combat capabilities of its forces that guarantee countermeasures, construction and modernisation of military infrastructure, and improved integrated control over air, surface and underwater activities in its Arctic zone.

[i]These developments are visible in new infrastructure deployed at various locations in the Arctic including Kotelny Island, Alexandra Land, Novaya Zemlya. These include air defence systems and other capabilities that add to its sea and air denial capacities. Russia has also unveiled a new base on Franz Josef Land which houses the Bastion missile launchers, and has airfields that are operational throughout the year. Similar refurbishment of airfields has been carried out across various locations in the Arctic. There has also been a steady rise in military exercises in the region to build up readiness and deal with various military and humanitarian needs. Chukotka Peninsula now houses the Bastion cruise missile unit, with Alaska being in its range, not to mention the access to Bering Strait. The Russian navy has also been expanding its capabilities, which was on display in March 2021 with three submarines emerging out of ice in the Arctic.

[j]In 2018, for the first time since 1991, US aircraft carrier Harry S. Truman conducted patrols in the Barents Sea. NATO’s Trident Juncture exercise in 2018 in Norway (which shares a border with Russia) was a show of force, with the scenario of NATO responding to armed attack under Article 5, involving foreign troops making an amphibious assault on the coastline near the Arctic. The US maintains radars in Greenland that can warn against missile attacks. In 2018, a Chinese company was barred from building an airfield in Greenland by Denmark. The Greenland-Iceland-UK-Norwegian (GIUK Gap) that forms a gateway between northern Europe and Atlantic, remains crucial for US interests. The superpower has temporarily deployed B1-Lancer squadron to Norway, set up a Maritime Operations Centre in Iceland, and carries out biennial submarine exercise ICEX with its partners to maintain operational readiness in the high north. Other Arctic states have stepped up, with Denmark increasing military spending in Greenland. Norway is refurbishing its naval bases to house US nuclear-powered submarines, and NATO members have been engaging in joint exercises to prepare themselves for Arctic conditions. In 2022, it will also host the largest military exercise inside the Arctic Circle in Norway since the 1980s.

[k]The legal status of the NSR being based on historical claims, and some Arctic straits being internal waters are not accepted by the US. It also calls for a narrow reading of Article 234 of UNCLOS to be limited to pollution by ships, is not a signatory to the 1982 convention. The differences over rights of coastal state vs international navigation between Russia and the US continues. At present, apart from disputing the Russian claims, the US has not engaged in freedom of navigation operations on the route. Experts believe that additional sanctions or FONOPs will endanger peace in the region.

[l] Under the rules of the Russian Merchant Shipping Code, ships require permission to navigate through NSR. Russia has also expressed concern regarding the Polar Code of the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) that came into force in 2017 over licensing of ships allowed to sail through Arctic, use of trained personnel, and quality of ships being permitted to navigate the ice covered route.

[m] The legal dimension of this issue is still being explored, as the 1982 convention did not anticipate the impact of climate change on ice-covered areas. The region becoming ice-free can lead to other countries questioning Russia over its argument regarding NSR navigation rules.

[n]An exception was granted in the case of Novatek which needed foreign vessels to transport its LNG in the absence of availability of Russian made vessels. The list now also includes activities related to ‘cabotage, icebreaker assistance, search and rescue operations, and marine resource research’ for which exceptions may be granted by the Russian government.

[o]According to UNCLOS, the territorial sea limit is set up at 12 nautical miles while the EEZ limit stands at 200 nautical miles, and within this area has the right to exploit and manage the natural resources present. This EEZ can be extended to 350 nautical miles (maximum) based on the extent of the continental shelf. The treaty defines continental shelf as follows: ‘the seabed and subsoil of the submarine areas that extend beyond its territorial sea throughout the natural prolongation of its land territory to the outer edge of the continental margin.’

[p] The Barents Euro-Arctic Council has as its members Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the European Commission.

[q] The United States and Russia have come together to create rules for ships traversing the Bering Strait and Bering Sea by identifying fixed corridors to prevent collision and protect the environment by avoiding ecologically fragile areas.

[r] The Chinese white paper on the Arctic says that it hopes to work with all parties to build a “Polar Silk Road” through developing the Arctic shipping routes. These routes are identified as Northeast Passage, Northwest Passage, and the Central Passage. The NSR is part of the first under Russian control, the second falls under what Canada calls its sovereign waters, while the third passes through international waters closer to the North Pole.

[s]Japanese investment in Arctic LNG 2 stands at about $5 billion, and it has tied up with Novatek to build an LNG terminal to distribute LNG to different buyers. Tokyo is reported to also be worried about increased Chinese presence in the Arctic. India is in talks with Rosneft for acquiring a stake in Vostok Oil in the Arctic. Talks are also reported to be ongoing regarding further Indian investment into Arctic exploration projects.

[t] Scholars argue that situation in the Arctic is hardly comparable to that of South China Sea.

[1]‘Investments in Russian Economy in Arctic to Exceed $86 Bln until 2025’, TASS, March 29, 2019,https://tass.com/economy/1051080.

[2]Dmitri Trenin, ‘Russia and China in the Arctic: Cooperation, Competition, and Consequences’, Carnegie Moscow Center, March 31, 2020, https://carnegie.ru/commentary/81407.

[3] Peter Hermes Furian, “Arctic Ocean map with North Pole and Arctic Circle,” https://www.123rf.com/photo_58784787_stock-vector-arctic-ocean-map-with-north-pole-and-arctic-circle-arctic-region-map-with-countries-national-borders.html

[4] “FOUNDATIONS of the Russian Federation State Policy in the Arctic for the Period up to 2035,” Russia Maritime Studies Institute, March 5, 2020, https://dnnlgwick.blob.core.windows.net/portals/0/NWCDepartments/Russia%20Maritime%20Studies%20Institute/ArcticPolicyFoundations2035_English_FINAL_21July2020.pdf?sr=b&si=DNNFileManagerPolicy&sig=DSkBpDNhHsgjOAvPILTRoxIfV%2FO02gR81NJSokwx2EM%3D

[5] ‘Key takeaways from the U.N. climate panel’s report,’ Reuters, August 9, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/key-takeaways-un-climate-panels-report-2021-08-09/

[6]‘Arctic Sea Ice Thinning Twice as Fast as Thought, Study Finds,’ The Guardian, June4, 2021, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jun/04/arctic-sea-ice-thinning-twice-as-fast-as-thought-study-finds.

[7]Amina Chanysheva, and Alina Ilinova, “The Future of Russian Arctic Oil and Gas Projects: Problems of Assessing the Prospects,” Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 9, no. 5 (2021).

[8]‘Russian LNG Projects Are Competitive — Shell Executive,’ The Moscow Times, March 21, 2019, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2019/03/21/russian-lng-projects-are-competitive-shell-executive-a64913.

[9]‘OPEC’s Spat Isn’t Even About Oil,’ OilPrice.Com, July 8, 2021, https://oilprice.com/Energy/Energy-General/OPECs-Spat-Isnt-Even-About-Oil.html.

[10]‘Russian Arctic Oil Races against Time,’ The Independent Barents Observer, May 6, 2021, https://thebarentsobserver.com/en/industry-and-energy/2021/05/russian-arctic-oil-races-against-time.

[11]‘Fossil Gas Has No Viable Future – EU’s Timmermans Says,’ EURACTIV.Com, March 26, 2021, https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/news/fossil-gas-has-no-viable-future-eus-timmermans-says/.

[12]‘Russia Faces Huge Revenue Losses From Renewables Push, Finance Minister Warns,’ The Moscow Times, July 8, 2021, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2021/07/08/russia-faces-huge-revenue-losses-from-renewables-push-finance-minister-warns-a74463.

[13]Chanysheva and Ilinova, ‘The Future of Russian Arctic Oil and Gas Projects.’

[14]‘The Arctic Region: Government Policy and Development Amid Conditions of Uncertainty’, Valdai Discussion Club, July 21, 2021, https://valdaiclub.com/events/own/the-arctic-region-government-policy-and-development-in-the-uncertain-conditions/.

[15]‘Russian Arctic Oil Races’ The Independent Barents Observer

[16]‘Six Ways Loss of Arctic Ice Impacts Everyone,’ WWF, accessed July 26, 2021, https://www.worldwildlife.org/pages/six-ways-loss-of-arctic-ice-impacts-everyone.

[17]‘Why Is an Ocean Current in the Arctic Critical to World Weather Losing Steam?’ National Geographic, 2 December 2019, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/why-ocean-current-critical-to-world-weather-losing-steam-arctic.

[18] Ekaterina Klimenko, ‘The Geopolitics of a Changing Arctic’, SIPRI, December 2019, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2019-12/sipribp1912_geopolitics_in_the_arctic.pdf.

[19]‘Foundations of the Russian Federation State Policy in the Arctic for the Period up to 2035,’ Russia Maritime Studies Institute, March 5, 2020, https://dnnlgwick.blob.core.windows.net/portals/0/NWCDepartments/Russia%20Maritime%20Studies%20Institute/ArcticPolicyFoundations2035_English_FINAL_21July2020.pdf?sr=b&si=DNNFileManagerPolicy&sig=DSkBpDNhHsgjOAvPILTRoxIfV%2FO02gR81NJSokwx2EM%3D

[20]Heather A Conley et al., America’s Arctic Moment: Great Power Competition in the Arctic to 2050, CSIS, March 30, 2020, https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/Conley_ArcticMoment_layout_WEB%20FINAL.pdf?EkVudAlPZnRPLwEdAIPO.GlpyEnNzlNx.

[21]‘Mission Report,’ NATO Parliamentary Assembly, May 10, 2017, https://www.nato-pa.int/download-file?filename=/sites/default/files/2017-07/2017%20-%20188%20JOINT%2017%20E%20-%20Mission%20Report%20Oslo.pdf

[22]Eugene Rumer et al, ‘Russia in the Arctic—A Critical Examination’, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 29, 2021, https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/03/29/russia-in-arctic-critical-examination-pub-84181.

[23]‘The Military Doctrine of the Russian Federation,’ The Embassy of the Russian Federation to the United Kingdom, June 29, 2015, http://rusemb.org.uk/press/2029.

[24]Alexander Sergunin, ‘Arctic Security Perspectives from Russia’ in Breaking the Ice Curtain?: Russia, Canada, and Arctic Security in a Changing Circumpolar World, ed. P. Whitney Lackenbauer et al (Calgary: Canadian Global Affairs Institute, 2019), 47.

[25]Danielle Cherpako, ‘What Is Russia Doing in the Arctic?’, NAADSN Policy Primer, August 7, 2020, https://www.naadsn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/20-August_Cherpako_What-is-Russia-doing-in-the-Arctic_-Policy-Primer-1.pdf.

[26]These include the restoration of 13 air bases, 10 radar stations, 20 border outposts, and 10 integrated emergency rescue stations.

[27]Matthew P. Funaiole et al, ‘Russia’s Northern Fleet Deploys Long-Range Interceptors to Remote Arctic Base’, CSIS, April 14, 2021, https://www.csis.org/analysis/russias-northern-fleet-deploys-long-range-interceptors-remote-arctic-base.

[28]Sergunin, ‘Arctic Security Perspectives,’ 50.

[29] “Arctic Sea Ice Summer Minimum 2020,” World Meteorological Organization, September 22, 2020, https://public.wmo.int/en/media/news/arctic-sea-ice-minimum-2nd-lowest-record

[30]Conley et al, ‘America’s Arctic Moment.’

[31]Cherpako, ‘What Is Russia Doing.’

[32]‘Russia says world’s largest nuclear icebreaker embarks on Arctic voyage,’ Reuters, September 22, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-russia-arctic-icebreaker-idUSKCN26D1FO

[33] Megan Drewniak et. al, “Ice-Breaking Fleets of the United States and Canada: Assessing the Current State of Affairs and Future Plans,” MDPI, https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/2/703/pdf

[34]Paul Avey, ‘The Icebreaker Gap Doesn’t Mean America Is Losing in the Arctic’, War on the Rocks, November 28, 2019, https://warontherocks.com/2019/11/the-icebreaker-gap-doesnt-mean-america-is-losing-in-the-arctic/.

[35]Eugene Rumer et al, ‘Russia in the Arctic.’

[36]‘Russian Radio-Electronic Shield Now Covers the Arctic,’ The Moscow Times, May 22, 2019, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2019/05/22/russian-radio-electronic-shield-now-covers-arctic-officials-say-a65680.

[37]Katarzyna Zysk, ‘Predictable Unpredictability? U.S. Arctic Strategy and Ways of Doing Business in the Region’, War on the Rocks, March 11, 2021, http://warontherocks.com/2021/03/predictable-unpredictability-u-s-arctic-strategy-and-ways-of-doing-business-in-the-region/.

[38]Sergunin, ‘Arctic Security Perspectives,’ 48.

[39] Klimenko, ‘The Geopolitics of a Changing Arctic.’

[40]Tyler Cross, ‘The NATO Alliance’s Role in Arctic Security,’ The Maritime Executive, July 19, 2019, https://www.maritime-executive.com/editorials/the-nato-alliance-s-role-in-arctic-security

[41]David Larter, ‘The US Navy returns to an increasingly militarized Arctic,’ Defence News, May 12, 2020, https://www.defensenews.com/naval/2020/05/11/the-us-navy-returns-to-an-increasingly-militarized-arctic/

[42]Mathieu Boulègue, ‘Russia’s Military Posture in the Arctic,’ Chatham House, June 2019, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/2019-06-28-Russia-Military-Arctic_0.pdf

[43]Nancy Teeple, ‘Great Power Competition in the Arctic,’ Network for Strategic Analysis, April 13, 2021, https://ras-nsa.ca/publication/great-power-competition-in-the-arctic/

[44]Sergunin, ‘Arctic Security Perspectives,’ 52.

[45] Ian Antony et al, ‘A Strategic Triangle in the Arctic: Implications of China-Russia-United States power dynamics for regional security,’ SIPRI, March 2021, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/sipriinsight2103_arctic_triangle_0.pdf

[46] Antony et al, ‘A Strategic Triangle.’

[47] Klimenko, ‘The Geopolitics of a Changing Arctic.’

[48]In 2017, a ship from China to Germany via the NSR took 23 days, while an alternative voyage through Suez Canal would have taken an extra 12 days. For more, see Sergey Balmasov, ‘Detailed analysis of ship traffic on the NSR in 2017,’ Nord University, October 19, 2018, https://arctic-lio.com/detailed-analysis-of-ship-traffic-on-the-nsr-in-2018/

[49]‘Putin’s Grand Target for Arctic Shipping Will Not Be Met’, The Independent Barents Observer, September 11, 2020, https://thebarentsobserver.com/en/industry-and-energy/2020/09/putins-grand-target-arctic-shipping-will-not-be-met.

[50]Alexandra Middleton, ‘Northern Sea Route: From Speculations to Reality by 2035,’ High North News, January 7, 2020, https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/northern-sea-route-speculations-reality-2035

[51]‘Cargo Volume on Northern Sea Route Remains Stable at 32m tons in 2020,’ High North News, September 30, 2020, https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/cargo-volume-northern-sea-route-remains-stable-32m-tons-2020

[52]Atle Staalesen, ‘Russian Arctic developers present a new dazzling target for Northern Sea Route,’ The Barents Observer, April 10, 2019, https://thebarentsobserver.com/en/arctic-industry-and-energy/2019/04/russian-arctic-developers-present-new-dazzling-target-northern . Some experts have raised questions regarding this target and believe that based on current volumes, the 80 million ton goal will be hard to achieve.

[53]Peter Danilov, ‘Northern Sea Route Transit Traffic Remains Modest,’ High North News, February 12, 2021.

[54] Malte Humpert, “The Future of the Northern Sea Route,” The Arctic Institute, September 15, 2011.

[55]Maxim Kulinko, ‘Interview: Russia’s Phased Approach to Northern Sea Route Development,’ The Maritime Executive, January 14, 2020.

[56]Kulinko, ‘Interview.’

[57]Jan Jakub Solski et al, ‘Introduction: regulating shipping in Russian Arctic Waters: between international law, national interests and geopolitics,’ The Polar Journal 10, no. 2 (2020), 203-208.

[58]Arild Moe, ‘A new Russian policy for the Northern sea route? State interests, key stakeholders and economic opportunities in changing times’, The Polar Journal 10, no. 2 (2020), 209-227.

[59] Cabotage refers to the right to operate and transport goods by sea, air or by other transport services within a particular territory.

[60]Viatcheslav Gavrilov, ‘Russian legislation on the Northern Sea Route navigation: scope and trends,’ The Polar Journal 10, no. 2 (2020), 273-284.

[61] Alexander Sergunin & Gunhild Hoogensen Gjørva, ‘The Politics of Russian Arctic shipping: evolving security and geopolitical factors,’ The Polar Journal 10, no. 2 (2020), 251-272.

[62]Pavel Gudev, ‘The Northern Sea Route: а National or an International Transportation Corridor,’ RIAC, September 24, 2018.

[63]Gavrilov, ‘Russian legislation.’

[64]‘Russian Policy in the Arctic: International Aspects,’ Higher School of Economics, April 2021.

[65]‘Amendm, ents to Merchant Shipping Code of Russia,’ The Kremlin, December 29, 2017.

[66]Gavrilov, ‘Russian legislation.’

[67] Moe, ‘A new Russian policy for the Northern sea route?’

[68]Sergunin & Gjørva, ‘The Politics of Russian Arctic shipping.’

[69]Gudev, ‘The Northern Sea Route.’

[70]David Auerswald, ‘Now Is Not the Time for a FONOP in the Arctic’, War on the Rocks, October 11, 2019.

[71]Auerswald, ‘Now Is Not the Time.’

[72] Klimenko, ‘The Geopolitics of a Changing Arctic.’

[73] Antony et al, ‘A Strategic Triangle.’

[74] Mika Okochi, ‘The Northern Sea Route International Law and Russian Regulations,’ EIAS, March 2020.

[75]‘Nicholas Breyfogle and Jeffrey Dunifon, ‘Russia and the Race for the Arctic,’ Origins, August 2012.

[76]Breyfogle and Dunifon, ‘Russia and the Race.’

[77]‘Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation,’ The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, December 1, 2016.

[78] “Continental shelf submissions in the Central Arctic Ocean,” Durham University Department of Geography.

[79]‘Arctic Council Strategic Plan 2021 to 2030,’ Arctic Council, May 20, 2021.

[80]‘Lev Voronkov: More profound cooperation between Arctic Council countries possible despite sanctions,’ The Arctic, May 25, 2021.

[81]Elizabeth Buchanan, ‘The U.S., Not Russia Is the New Spoiler in the Arctic,’ The Moscow Times, May 15, 2019.

[82] Klimenko, ‘The Geopolitics of a Changing Arctic.’

[83]Lev Voronkov, ‘The Arctic for Eight,’ Russia in Global Affairs, June 30, 2016.

[84] Elizabeth Buchanan and Bec Strating, ‘Why the Arctic is not the next South China Sea,’ November 5, 2020.

[85]‘A Blue Arctic: A Strategic Blueprint for the Arctic,’ The Department of Navy, January 2021.

[86] Buchanan and Strating, ‘Why the Arctic is not the next South China Sea.’

[87] Antony et al, ‘A Strategic Triangle.’

[88]Camilla T. N Sørensen and Ekaterina Klimenko, Emerging Chinese-Russian Cooperation in the Arctic: Possibilities and Constraints, SIPRI, June 2017.

[89] Antony et al, ‘A Strategic Triangle.’

[90]‘China’s Arctic Policy, ‘Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China,’ January 26, 2021.

[91] Buchanan and Strating, ‘Why the Arctic is not the next South China Sea.’

[92] Trenin, ‘Russia and China in the Arctic

[93] Antony et al, ‘A Strategic Triangle.’

[94]Trenin, ‘Russia and China in the Arctic.’

[95]‘Alaska: Biden to suspend Trump Arctic drilling leases,’ BBC News, June 2, 2021.

[96] K M Seethi, ‘The Contours of India’s Arctic Policy,’ The Arctic Institute, August 3, 2021.

[97] Buchanan and Strating, ‘Why the Arctic is not the next South China Sea.’

[98] Moe, ‘A new Russian policy for the Northern sea route.’

[99]Antony et al, ‘A Strategic Triangle.’

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

Source:

Source:

PREV

PREV