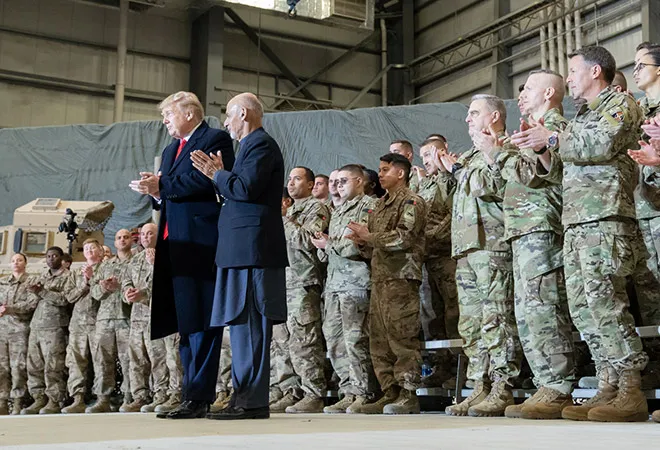

US President Donald Trump’s unannounced visit to Afghanistan for the ostensible purpose of celebrating Thanksgiving Day and his surprise invitation to Afghan President Ashraf Ghani for an official visit to Washington needs to be assessed in the context of his desperation to restart negotiations with the Afghan Taliban, which were abruptly terminated by him when the peace deal had seemed very close to being signed. This was Trump’s first visit to Afghanistan since becoming president.

The US president’s willingness, or rather desperation, to withdraw from Afghanistan has never been in question. He wants a substantial number of American soldiers brought back from the war-torn country with or without an exit strategy, before the 2020 presidential election. India has always feared this expedient haste, as it only undermines the Afghan government by signalling a lack of American resolve. New Delhi would like the Trump administration to work towards an agreement that supports the democratic forces in Afghanistan, rather than endangering them. Since he has had no real alternatives to reviving talks, Trump has chosen to pick up where he left off in September.

In Afghanistan, Trump has demanded a “ceasefire” as a precondition for talks with the Taliban. Demanding a ceasefire can be termed a historic shift in Washington's position, which would also require a huge concession from the Taliban. This is the second time in a week that Trump has talked about a ceasefire. During his telephone talks with his Afghan counterpart a few days back, when he thanked Ghani for his cooperation in the release of two foreign professors by the Taliban in exchange for three insurgents, Trump had stressed the need for the ceasefire as a precondition for talks.

This is a very significant position taken by the US president, who has hinted at a change in the Taliban’s position: “They didn’t want to do a cease-fire, but now they do want to do a cease-fire, I believe. And it will probably work out that way. And we’ll see what happens.” However, the Taliban does not seem to have made any change.

India, which has a huge stake in the Afghan peace process, would like Trump to stick to the ceasefire precondition. New Delhi has always cautioned Washington about the peace process with the Taliban in Afghanistan, advocating the role of the elected Afghan representatives in deciding the nation’s future.

In the recent UN General Assembly debate on Afghanistan, an Indian diplomat in India’s UN Mission had argued that “while the international community must be united in supporting these efforts, we do not believe in advancing prescriptions. In any country, it is the people of that country and the elected representatives of that country who should have the leading voice in deciding their future — this has always been one of India’s guiding principles in its engagement with Afghanistan.”

Without a ceasefire, intra-Afghan negotiations cannot succeed. Apart from the ceasefire, another sticking point has been the involvement of the Afghan government in the process. The ostensible reason for ending the talks in September was the Taliban’s claim of responsibility for a terror attack that also led to the death of an American soldier. In addition to calling off the peace process, Trump had also cancelled his planned meeting with Taliban leaders and Ghani at Camp David.

There is speculation whether the US president wanted to improve the deal’s terms through his direct involvement, or whether Ghani’s presence at the signing ceremony was a clever ploy by Trump to legitimise the role of the Afghan government. Given the military stalemate in Afghanistan, the suspension of talks has not improved America’s limited set of options.

The Taliban have not demonstrated any enthusiasm for sharing power with the Afghan government; their fundamental interest lies in overthrowing it. Even as talks with Special US Envoy Zalmay Khalilzad were underway, violence from the Taliban side showed no decline. The belief that the Taliban showed increasing willingness to join the Afghan mainstream, as they remained invested in the process, was actually propagated by those in Pakistan who insist on a peace deal at all costs.

If anything, the Taliban’s ultimate aim is not to secure peace, but to finalise a deal that triggers American withdrawal and clears the way for its ascent to power in Kabul.

Had the deal been signed in September, it would have seen thousands of American troops withdrawn in exchange for guarantees by the Taliban that Afghanistan would not be used as a base for terror attacks on the West. But New Delhi has been sceptical about the Taliban’s ability to prevent Al-Qaeda and other terrorist groups supported by Pakistan’s intelligence agencies from plotting attacks against India from Afghan soil.

Since avoiding diplomacy is costly for all sides, it is a matter of time before the Trump administration goes back to the negotiating table. However, the terms of negotiations are equally important. Even those in India who accept in principle the need for a negotiated settlement have been against Washington's desperation for negotiating exclusively with the Taliban, without securing an early ceasefire. This approach goes against the basic American position that the peace process should be “Afghan-led and Afghan-owned”.

Trump has probably come to realise his previous mistake and so seems to be reinforcing the need for a ceasefire if the talks are to begin between Khalilzad and the Taliban representatives. Yet, given Trump’s mercurial disposition and the imperatives of domestic politics, there is no guarantee that Khalilzad would necessarily insist on this precondition in his talks with the Taliban, which can begin any time now. And therein lie the dilemmas of Indian policy towards Afghanistan, which remains dependent on Washington’s policy responses.

This commentary originally appeared in Business Standard.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV