Introduction

India agreed to start shipping cargo along the 7,200-km International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) in December 2016.[i] Latest media reports indicate that the Indian public sector companies are to be the first users of the part-ready corridor.[ii]

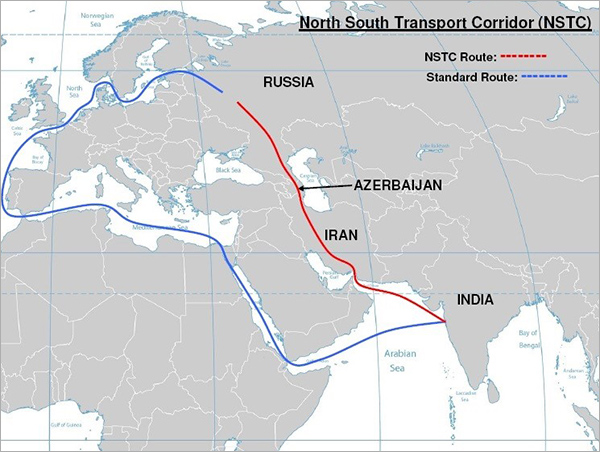

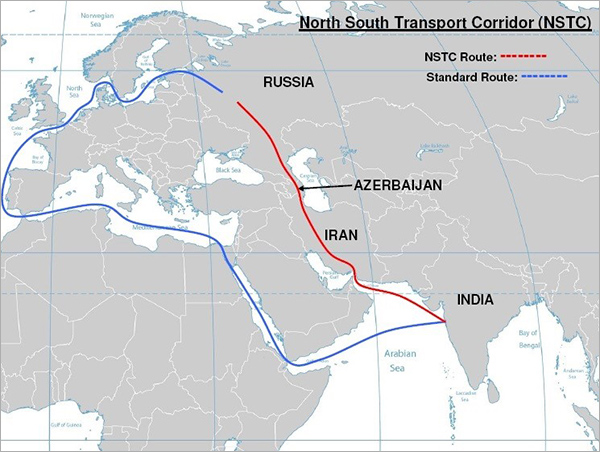

Agreed upon in 2000 and ratified in 2002 by the three founding members, India, Iran and Russia, the original multimodal route—from Mumbai in India to Bandar Abbas and Bandar-e-Anzali in Iran, then across the Caspian Sea to Astrakhan, Moscow and St. Petersburg in Russia—had not seen much traction given sanctions on Iran. Recently, however, the INSTC project has moved forward with Tehran back in the international fold and the 2016 agreement on Chabahar port―which will likely be tapped as a second, or alternative, to the Bandar Abbas port. Countries that have subsequently joined the regional project, in particular Azerbaijan, have been eager to connect to the INSTC and are pursuing projects that seek to diversify the original route. A dry run conducted in 2014 pointed to an alternate route using Azerbaijan’s capital, Baku, as a transit point between Iran and Russia. Trial runs conducted in August 2016 also ran through both Iran and Azerbaijan. Goods will be shipped to the southern Iranian port of Bandar Abbas and will arrive in Russia through Azerbaijan via trains and trucks, avoiding the need to be shipped across the Caspian Sea as planned initially. Baku is being developed as a transport hub.

Figure 1: The new route versus the old

The Azerbaijani and Iranian rail networks are in the final stages of being linked together[iii] after an agreement[iv] was recently signed by the leaders of Iran, Russia and Azerbaijan to establish a transport corridor linking the three countries. Earlier in March 2017, the three countries agreed to cut tariffs in a bid to encourage trans-border trade via the INSTC.

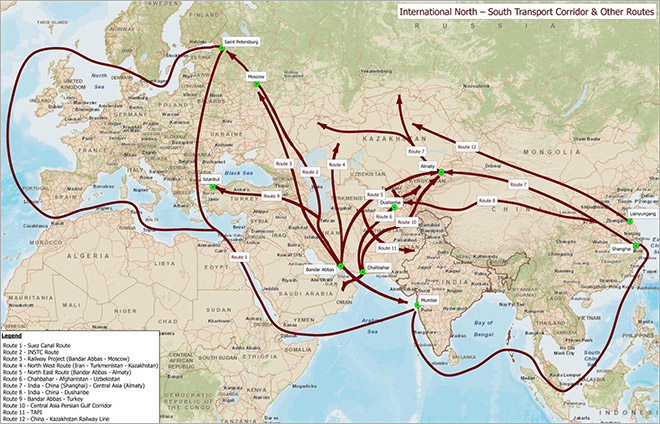

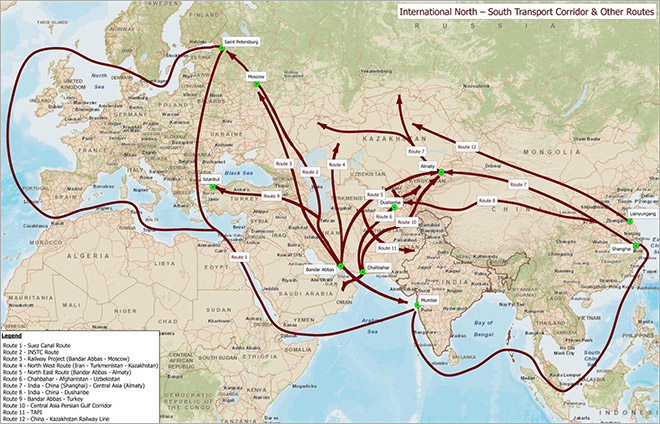

Other routes through Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan are also under consideration (among them, the Kazakhstan-Turkmenistan-Iran railway link). Countries in the region are also building bilateral railway connections, as is the case between Armenia and Iran. Further, with India linking up with Myanmar and Thailand by road with the development of the Trilateral Highway, there exists a likelihood for a longer transport belt that connects Southeast Asia to Europe through the INSTC. Equally noteworthy is the interest in developing the INSTC in the western direction: the German railway company Deutsche Bahn has expressed interest in using the INSTC to deliver goods from Europe, though Azerbaijan, to Iran.[v] More recently, in January this year, Estonian Foreign Minister Sven Mikser also expressed interest in joining the INSTC; his office has already begun negotiating with current members.[vi]

Effectively, there are several existing, planned and under-construction routes, some of which link up to the original INSTC, that are forming a network of connectivity across the Eurasian landscape (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The connectivity mosaic across Eurasia[vii]

This emerging, larger mosaic of routes and railways means a greater web-like connectivity in Central Asia that India will finally be able to access through Iran. India’s decision in March 2016 to accede to the Ashgabat Agreement, which aims to establish an international transport and transit corridor linking the Central Asian countries to Iranian and Omani ports, will “synchronize [New Delhi’s] efforts to implement the…INSTC”[viii] and is testament to its desire to ‘Act West’ and enhance trade and commercial interaction with the landlocked region. Specifically, India will gain access to raw materials and be able to enhance energy ties that could help diversify its imports and advance its long-term interests vis-à-vis crude oil and natural gas. India will also have the opportunity to fulfil the potential of current markets and cultivate future ones. Importantly, the INSTC will allow India to bypass Pakistan, a neighbour with which it has contentious relations and is not currently, nor in the near future, a viable option as a transit country.

Moreover, in November 2016, the first Chinese shipment of goods successfully passed from the north to the south of Pakistan before being shipped from Gwadar port towards destinations in the Middle East and Africa. It is likely that the launch of the first set of goods from Gwadar, a competitor to Iran’s Chabahar port that India is invested in, played a role in the decision to officially begin using the INSTC. (Given that the INSTC found but mild mention in the joint statement[ix] issued following the Modi-Putin meeting in early November 2016, it is likely that the Gwadar port was a major determinant in India’s decision to start using the INSTC the very next month.) The link between Chabahar port and the INSTC is explored in latter sections of this paper.

These advantages and motivations for India underscore the need for New Delhi, as the country begins to use the INSTC, to fully evaluate the economic rationale of a venture that primarily speaks to commercial reason. Two contextual factors heighten the necessity: 1) regional connectivity in previously less-connected spaces, such as Asia, is being seen as a means to continue domestic development as traditional heavyweight trade partners in the West continue their slow and uncertain recovery; and 2) as the evolving politics in the region push New Delhi to re-examine what tangible geopolitical capital it stands to gain from this initiative, it may be the smarter option to recommend the INSTC on its economic merits.

The following exercise will help understand the present and potential scope of the INSTC, and thus its long-term prospects; strengthen arguments for or against its use and further expansion; and allow for a greater appreciation of the extent the economics of the project need to play a role when deliberating on the INSTC.

The paper first looks at the commercial advantages of a transport corridor, seeing where the INSTC holds up and where it falls through. It then discusses key factors that, if borne in mind, strengthen the INSTC’s economic rationale for India. The last section sets the conversation in the context of broader regional and global politics and what they mean for India’s strategic gains via the INSTC and Chabahar port. The paper concludes that in an international context filled with uncertainty—and especially as none of the INSTC stakeholders have the economic wherewithal to shoulder a commercially unviable venture—the INSTC should be nurtured as a commercial project and the focus should be on reaping its economic advantages.

The Economic Advantages of a Transport Corridor

A transport corridor fundamentally connects “major sources of trips”―population centres and centres of economic activity―through a general directional flow.[x] The economic case for a transport corridor, therefore, lies foremost in facilitating transit and enhancing access to markets. The INSTC, for instance, will provide India more direct access to Central Asia and Russia. At the same time, it will allow Iran and Azerbaijan to become regional transit hubs. A second factor is the creation of regional supply chains—or a “consumer-producer network” across Eurasia that seeks to reverse, in time, the traditional model of the East as producer and the West as consumer.[xi] Asia is projected to account for 66 percent of the world’s middle class by 2030, who are expected to possess considerable spending power.[xii] The development of Asia as a strong consumer market will take time—currently, exports remain heavily westward-focused along existing transport routes across Eurasia. For instance, only a few China-Europe railway routes operate in both directions, and on such routes, trains are returning from European cities with significantly lighter loads. In fact, the Chongqing-Xinjiang-Europe freight route, or the Yuxinou train, only began bringing back goods two years into its service.[xiii] Returning empty containers along the INSTC (north to south direction) is a key concern recognised by various stakeholders. However, as Gleb Ivashentsov of the Russian International Affairs Council notes, there is a lack of information about the Indian market among Russian businesses.[xiv] Moreover, household consumption in South Asia has increased by 130 percent more than the overall global figure between 2001 and 2013, and the region has added more than the entire population of France as urban citizens.[xv] Consumer demand is thus present, and bridging the knowledge and communication gap could make the INSTC a true two-way connectivity route.

A third economic advantage comprises of shorter distances and faster deliveries, which translate to lower capital and overall costs: the Yuxinou train cited above takes on average only 14 days from departure to arrival, one-third the time it would take to transport the goods by sea, and one-fifth the cost of sending goods by air. The INSTC, too, has equal grounds on which to stake such commercial merit—the 2014 dry run[xvi] showed the newer route to be 40 percent shorter and 30 percent cheaper than the traditional route taken through the Suez Canal. Other available figures indicate that it would take half the time from Mumbai to Europe and Russia on the INSTC than along the sea route, and savings amount to the tune of $2,500 for every 15 tonnes of cargo.[xvii] What is more, existing railway connectivity between Iran and Turkey mean that distances between Istanbul and Delhi, too, could be reduced (by two weeks) using the inland route. Turkey has already offered to provide information to link the INSTC secretariat to the Organisation of the Black Sea Cooperation, a regional grouping that, among other things, fosters trade links.

Given cheaper costs of transportation, increased competitiveness is another factor that makes an economic case for transport corridors. The INSTC is expected to boost the competitiveness of India’s trade. With easier access to unfulfilled markets, there is potential for not just India but other INSTC members to increase production and lower costs. The chances of this happening are higher, given the more level-playing field among India and the other INSTC members, than compared to, say, China’s trading strength—especially given its current overcapacity—versus those of most of its trading partners around the world. And yet, as Oleg Larin of the Russian Institute of Strategic Studies points out, it is unclear whether the price of Indian goods that arrive in Russia will be cheaper than Chinese goods that still retain manufacturing competitiveness.[xviii]

Another aspect of competitiveness is that of the entire route against other emerging overland transport corridors if missing links (such as the Qazvin-Rasht-Astara rail link) are built and non-infrastructure-related hurdles are overcome. The INSTC could compete with other corridors (such as China’s Silk Road Economic Belt) as a transit route between Southeast Asia and Europe, for example. ASEAN and the EU are each other’s third- and second-largest trading partners, respectively; the INSTC will functionally buttress the bilateral FTAs that have been concluded or else are in the pipeline.

Lastly, shorter, faster and cheaper transport corridors could mean an increase in goods and services traded, which in turn implies the strengthening of trade and, overall, of bilateral ties between countries and regions. For example, the Yuxinou train that began in 2011 as a weekly service from Chongking to Duisburg now makes the trip eight times a week; German-Chinese trade[xix] has doubled approximately every five years between 2004-2014. The upcoming Belt and Road Summit in May this year will see an assessment of the direct impact of operational China-Europe trains.[xx]

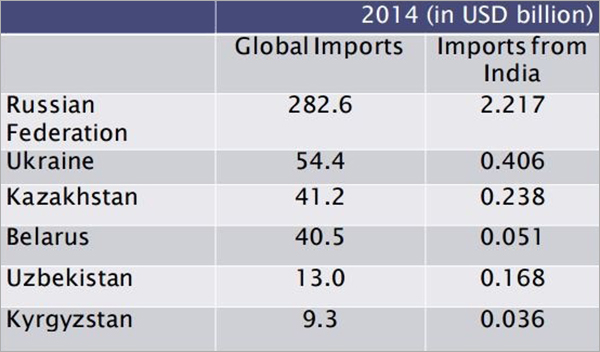

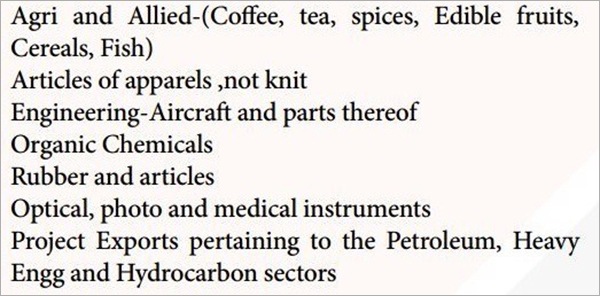

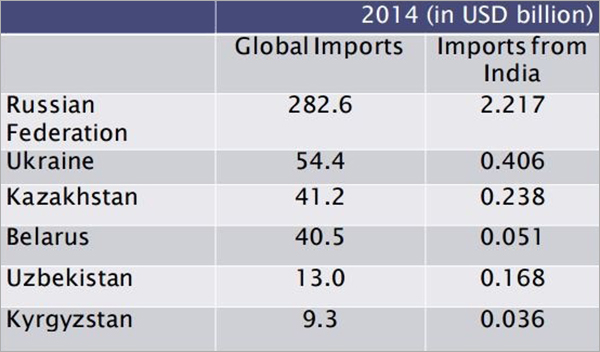

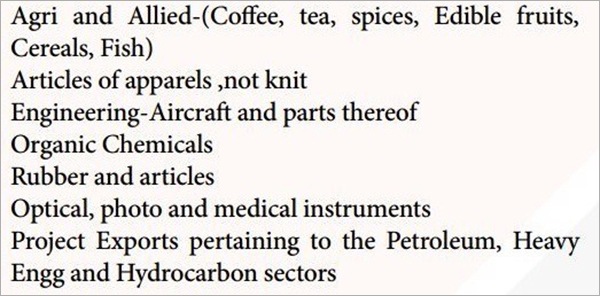

It would be extremely useful to similarly calculate what impact using the INSTC will have on bilateral and inter-regional trade.[xxi] At present, trade volumes between India and several other countries/regions are dismal; often cited as a reason is lack of connectivity. For example, India’s share of exports to the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) region is currently less than one percent (Figure 3). However, bilateral trade between India and the CIS region has been inching upward—from $8 billion in 2010-11 to $11 billion in 2014-15.[xxii] Discussions are ongoing on a free trade agreement between India and the Eurasian Economic Union; such an FTA potentially advances the transport corridor’s utility in facilitating trade. India’s primary export promotion body has already identified potential export sectors that will immensely benefit from the INSTC (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Share of imports from India to countries in the CIS region[xxiii]

Figure 4: Potential export sectors identified for India[xxiv]

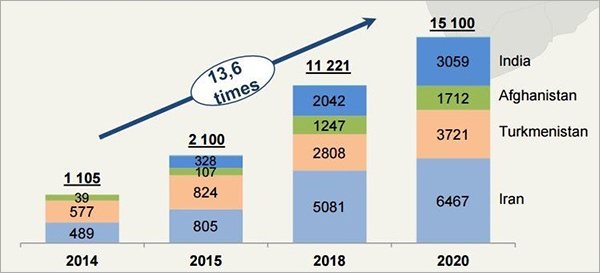

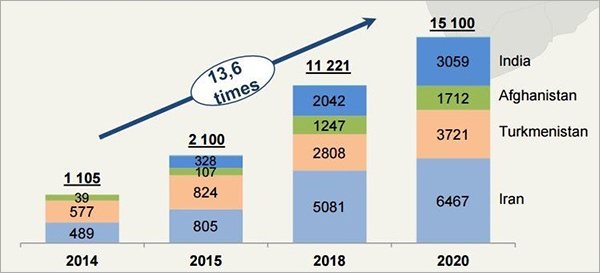

Furthermore, initial forecasts on freight traffic along various stretches of the INSTC show growth potential (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Forecast on freight traffic between Kazakhstan-Turkmenistan-Iran (in thousand tonnes)[xxv]

However, worryingly, the volume of trade between India and Russia fell by more than 10 percent in 2016[xxvi] (at $3.4 billion, for comparison, this was less than a 1/10 of the value of China-Russia trade in the same period[xxvii]). Moreover, freight railway transportation along the proposed INSTC routes on segments that are already in place has seen a 1.8 percent dip from 12.6 million to seven million tonnes from 2007 to 2014.[xxviii] In May 2016, Russian Trade Representative to India Yaroslav Tarasyuk identified “[t]he very complicated logistics” as the primary obstacle to trade with India, and subsequently expressed the hope that the INSTC starts operating soon.[xxix] At the same time, it may seem counterintuitive to deduce that the availability of direct, faster routes will encourage growth in the volume of goods traded: these routes may still not provide sufficient stimulus if depressing trade trends become the norm.

Having said that, both hard and soft infrastructure development in emerging markets is expected to stimulate aggregate demand and generate growth. Various studies have shown quantifiable, significant increases in trade flows for both exporting and importing economies in Asia with improvement in transport infrastructure, particularly road and port.[xxx]

Not a Road to Nowhere: Making the Economic Case for the INSTC

The earlier section showed that overland transport corridors offer a host of economic advantages and that the INSTC stands in good stead. There are valid concerns, however, regarding expected throughput volumes that will negate the benefits of a shorter, faster route. INSTC countries must enforce policy measures such as financial support mechanisms and agreements to settle trade in national currencies to boost both investments for developing missing links, and exports. This section discusses the tangible, non-policy-oriented factors that, if addressed, will help make an economic case that India and the other INSTC stakeholders can pursue.

Rail freight versus maritime shipping

A conscious consideration of this first essential will help in defining the economic potential of the INSTC. Around 90 percent of current world trade passes through sea lanes of communication; transport corridors should therefore complement sea shipping, with the aim of keeping sufficient traffic on the roads and rail tracks to remain economically viable.

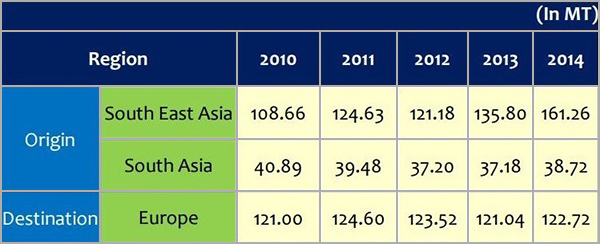

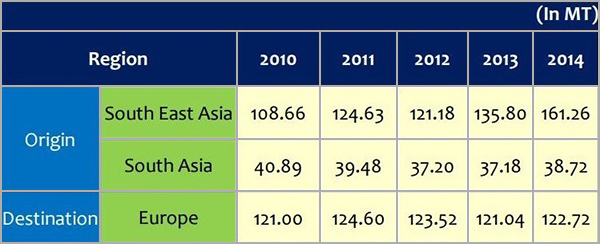

In May 2016, the Global Times reported[xxxi] a supply glut in the global shipping industry, which has meant that companies have been forced to slow down their ships to cut costs. Longer periods spent at sea, in turn, have led to the maintenance of larger inventories, freezeing up more assets and shortening the shelf-life of products. More recently, The Economist confirmed that the global shipping industry is seeing its worst slump in three decades due to oversupply and shrinking trade volumes.[xxxii] Even as overland transport routes offer more timely delivery with less inventory costs, any such comparative advantage is eroded by the cheaper rates shipping liners are offering in the face of a slump in demand. It is therefore still approximately five times cheaper to ship via oceans than by iron silk roads.[xxxiii] It has been estimated that the entire Silk Road Economic Belt, with its network of transport corridors and rail routes, will only account for one to two percent of overall freight traffic; INSTC, as it stands at present, is only one particular workable route which will obviously move a significantly lower level of container trade. Available estimates peg the volume of container trade expected in the first phase of the INTSC at four to 10 million tonnes, which is likely to increase to 25-26 million tonnes per annum in the future.[xxxiv] There is also a more conservative estimate of five million tonnes of cargo per year in the initial phase, increasing to a low 10 million tonnes “with further expansion of transportation.”[xxxv] This volume of goods is nowhere near that being transported from South and Southeast Asia to Europe via the admittedly overloaded Suez Canal (Figure 6). Further analysis is necessary to examine what percentage of deflected volume from the Suez Canal will incentivise the use of the INSTC.

Figure 6: Volume of goods from Southeast Asia/South Asia to Europe via Suez Canal[xxxvi]

Recognising this clear obstacle of a lack of volume will encourage the INSTC member states to look to other commercial justifications for the use of the corridor. It is worth discussing, for instance, the possibility of stimulating local industry and manufacturing along the way, and thus eventually transforming the transport corridor into a developmental corridor. Creating industrial parks, or special economic zones to develop sectors of mutual interest, such as pharmaceuticals and agriculture, will add commercial and substantive value to the INSTC. The development of local logistics hubs that will feed into the INSTC (such as Nagpur and Bhiwandi in the Indian state of Maharashtra, home to the Mumbai port) are a step in this direction.

Type of goods

Another point of consideration that can help justify using the INSTC is the kind of goods that are to be transported along the corridor. Railroads provide an optimal medium between slow and cheap, and quick and expensive. As officials running various train services from China bound westward recognise, there is an opportunity to become part of the “modern supply chain… characterised by smaller orders, multiple dispatches and high-delivery frequencies.”[xxxvii] Perishable goods are a good bet, which can be moved timely at lesser costs, and the first containers with perishable goods have already started making the journey across the Caspian Sea to the Astrakhan region.[xxxviii] Given that the European Union (EU) is the destination of over 50 percent of India’s total export basket of fruits and vegetables,[xxxix] it makes commercial sense to use the shorter INSTC route to transport such perishable items, as well as meats, seafood and foodgrains, from where the goods can be quickly sent along to the UK, Netherlands, Germany, Belgium (major export destinations) and the rest of the EU. Goods with inelastic demand, such as the coffee being sourced from Vietnam, processed in China and shipped to Europe, are also viable commodities to transport by railways.

So are higher-value items like ATMs, industrial printers, 3D printers and robotic assembly arms, which no longer need to be waited upon to be transported in bulk. Along the weekly train from Suzhou to Warsaw, for example, DHL is able to ship one ATM at a time or as per their customers’ requirements:

“If you have an ATM out of order the customers start to complain and you have to replace it as soon as possible, so you can only fly it. One ATM machine is 800 kilos, so that’s going to cost you a lot of money. Now, you can ship by our service and in three to four weeks [as compared to the traditional six to eight weeks] you can have the ATM machine ordered and installed. They don’t have to wait for a whole container load, they can ship just one ATM machine.”[xl]

While China’s development of westward-bound connectivity infrastructure is being strategically linked to the planned transition of its economy from low-end to high-end manufacturing, the same cannot be said of the INSTC and the involved stakeholders. Trade between India and both Russia and the CIS is still inclined towards primary commodities and lower-end manufactured products. Yet indicators such as the top Indian export commodity to Russia―pharmaceutical products[xli]―provide some existing platform for India to invest in a higher-end manufacturing industry such as pharmaceuticals at home. Furthermore, Russia’s deteriorating relationship with the West already led the Indian commerce ministry in 2014[xlii] to identify items for export to Russia that the latter has traditionally imported from the US or the EU. These include higher value-added goods like vehicles, aircraft and spacecraft, optics and electrical machinery. An improvement in the quality of trade will galvanise the use of the INSTC.

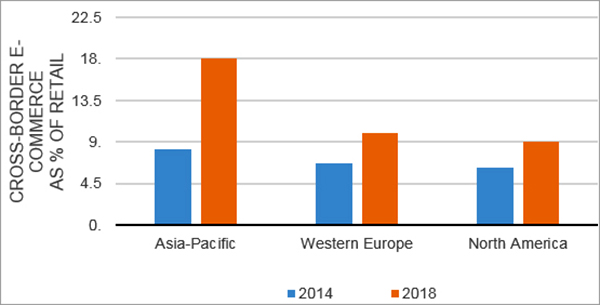

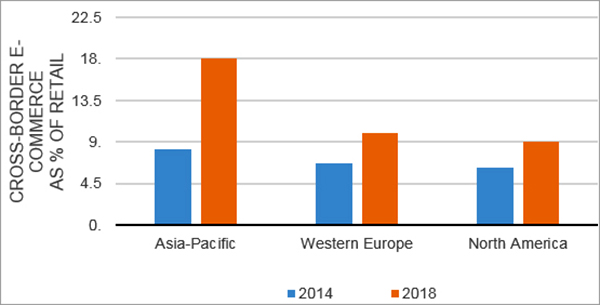

Even more interesting is the potential of expanding e-commerce delivery through rail. Even as global e-commerce remains a small percentage compared to domestic e-commerce, it is flourishing while global trade growth has been slow to pick up. Cross-country e-commerce is a trend that is here to stay, particularly as internet connectivity proliferates across the regions that are adding the most citizens both online and in a consuming middle class (Figure 7). Take, for instance, Russia, where cross-border e-commerce is growing faster than domestic e-commerce.[xliii] Business-to-consumer cross-border e-commerce market is estimated to reach $1 trillion by 2020.[xliv]

Figure 7: Cross-border e-commerce is flying high[xlv]

International postal services as well as local companies that drum up international business electronically could therefore become viable sources to keep transport corridors financially healthy. With national priorities including a focus on domestic digitisation (for instance, the Indian government’s ‘Digital India’ initiative) and plans to increase digital connectivity in and across regions, e-commerce as a good that is transported via the INSTC holds significant potential in the coming years. India will need to significantly scale up its logistics to become a consequential player. As of now, Aurangabad in Maharashtra has been identified as having the potential to emerge as a hub catering to e-commerce firms.[xlvi]

Lastly, energy as a transportable commodity can also be discussed. While energy infrastructure is not a part of the connectivity project, pipeline infrastructure that either runs along railway tracks or complements the multimodal transport corridor is not too difficult to imagine. Important to cite here are the proposed Iran-Oman-India pipeline and India’s interest in importing crude oil from Kazakhstan. Shorter distances will strongly play into the calculations. So will the fact that it is generally twice or even three times cheaper[xlvii] to transport crude oil by pipeline than by railway, and that conversely, railways offer a significant speed, and thus time, advantage. As Iran’s railway system is developed, and as negotiations progress for the undersea pipeline, some thought should be spent on recalibrating the overall economic worth of the INSTC venture, keeping in mind potential energy transports and an increasing energy demand in the Asia-Pacific region.

Non-tariff barriers: Customs

Another criteria that can significantly curb trade barriers and streamline the flow of goods relates to the technical and regulatory trade barriers. These include customs, changes of gauge, lack of IT and digitisation, and the absence of a single multimodal operator and therefore single tariff rate. On the customs front, there has been some movement by the INSTC countries who have approved a draft transit and customs agreement. The green corridor arrangement between India and Russia―which will exempt from regular customs inspections goods from entrepreneurs and companies party to the arrangement―will also smoothen the passage of cargo at borders. A test run may soon be held along this green corridor to commemorate 70 years of Indo-Russia diplomatic ties. Customs infrastructure that can handle bigger consignments along various stretches of the route should be a priority agenda item: as the Vice Chairman of the Indian national freight agency charged with conducting the 2014 dry run pointed out, “the infrastructure was available and the security was not a real concern, however streamlining and co-ordinating [passage of cargo] with some of the allied agencies was the major concern.”[xlviii]

There are several recourses available to improve cross-border transit being used by other trans-regional corridors that can be adopted by the INSTC countries. These include green channels; 24-hour customs clearances that can be utilised through prior appointment; special declaration channels; digital technologies for one-stop custom declaration, checking and clearance; and adoption of ‘declare at home, release at port’ model.

International treaties, such as the UN trucking treaty TIR (formally the Convention on International Transport of Goods Under Cover of TIR Carnets), are also further options to streamline the passage of cargo. A further advantage, as has been evident from Turkey’s case, is that being part of the TIR will help develop the competitiveness of domestic road transport industries.[xlix] Becoming a member of the TIR will allow customs-sealed vehicles and freight containers from India to pass through the Eurasian landmass all the way to Ireland without having to be subjected to border checks (save random ones). Like China last year, India too recently decided to sign the only global customs transit system in existence (in what has been understood as proof of Indian resolve to use the INSTC). It will soon become the 71st signatory. Oman will then be the only INSTC member not part of the convention.

Meanwhile, India’s accession to the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) in June will likely include it having to ratify the intergovernmental sub-regional road transportation facilitation agreement that the SCO drafted for itself in 2014. More efficient transportation through common border crossing rules boosts INSTC’s financial viability, particularly given the overlap between SCO and INSTC members. With India’s eventual accession to the Ashgabat Agreement, the scope expands for synchronised customs rules, regulations and practices in Central Asia.

Non-tariff barriers: Change of gauge

Change of rail gauge is another barrier worth mentioning in some detail. Like customs, this is also a hurdle being experienced by other cross-border railways. For instance, the standard rail gauge used by China is smaller than the broad gauge in use in the Commonwealth of Independent States and Russia. This means that freight moving from China westward has to be transferred from one rail track to another of varying width using cranes, which is more difficult with containers. Even as time to transport a container overland is cut by at least half of what it would take by sea despite different railway gauges across the journey, there is scope for improvement. To this end, China is planning an entirely separate, parallel route—the China-Europe Silk Road Railway—using the standard gauge preferred by China and Europe. The objective is to establish a seamless track for a high-speed all-standard gauge rail service, which will be cleared by customs just once and will arrive from one to the other in just 3.5 days.[l]

Coming to the INSTC, goods were to be originally transported by rail in Iran before being shipped cross the Caspian Sea to arrive at a fresh set of rail tracks in Russia. Now, railway linkages that connect to Central Asia and Russia are to be used, going through Baku, and perhaps eventually through other Central Asian options on the table. This means the INSTC, too, will face break of gauge problems, seeing as the railway gauge in Iran differs from what the former Soviet space has in place. It has been suggested that combined rail terminals with change of gauge facilities be constructed at international borders to ease transfer from one railway track to another.[li] What makes the conversation geopolitically sensitive is the fact that Iran is at the crossroads of the INSTC and China’s Silk Road Economic Belt. Iran currently has less railway track laid down than the UK, a country seven times smaller. The end of UN sanctions on Iran has seen it being courted by European companies, as well as Russia and China, to help Iran modernise and expand its railway system. China’s high-speed standard gauge line running through Central Asia “would slice a knot of broad gauge lines in the states of the former Soviet Union, and speed up the flow of goods to Europe,”[lii] reinforcing movement of goods east to west, potentially at the expense of the north-south pathway.

Financing and returns on investment

Another key factor that will determine the economic rationale of the INSTC is the financing. Securing it will involve, among other things, keeping in mind what returns on investments to expect.

The INSTC is currently a precise project in its scope. Different stretches of the transport corridor and other complementary routes are being funded by different stakeholders instead of being dependent principally on one actor. For instance, the crucial missing Rasht-Astara railway link that connects Iran to Azerbaijan is estimated to cost just over $1 billion; of this, $500 million will be provided through a loan from Azerbaijan. Iran and Azerbaijan are now looking to secure the rest of the money. Another actor is the Asian Development Bank, which is to provide a loan worth $200 million for the construction of the Baku-Yalama (in Russia) rail link (although the bank has “postponed consideration of the possibility of allocating” this sum to this year[liii]). The ADB and the Islamic Development Bank have both contributed loans to the Kazakhstan-Turkmenistan-Iran railway link, which is otherwise being funded by the governments of the three countries. India will invest $500 million to develop the Chabahar port, as well as provide a line of credit to make berths at the port.

Interest evinced by Japan to invest in the Chabahar port indicates that non-INSTC members―such as Southeast Asian countries which would directly benefit from an alternate trade route―could be tapped to successfully implement the transport corridor to its fullest potential. Japan’s foreign ministry has now twice expressed that it would seriously consider proposals to improve connectivity between Iran, Afghanistan and Central Asia,[liv] and the Chabahar port was discussed specifically at Modi and Abe’s meeting in November 2016:

“The two Prime Ministers welcome the prospects of cooperation between the two countries for promoting peace and prosperity in South Asia and neighboring region, through both bilateral and trilateral cooperation, inter-alia, in the development of infrastructure and connectivity for Chabahar.”[lv]

Slow-moving funds could prove to be a real obstacle, however, despite the involvement of a number of countries and international institutions. This is a real worry given that the involved countries are looking for foreign investments themselves, and face the challenge of balancing several imperatives all at once. Importantly, Russia is still under sanctions—although it is debatable how much this has affected business in reality—and infrastructure involves significant investment that may not be readily forthcoming in an environment of global economic stagnation—ironically, the very constraint such transport corridors would like to alleviate.

To provide some situational awareness, albeit loosely, given the larger scope of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, Chinese officials have privately admitted that they expect to lose 80 percent of their investment in Pakistan, 50 percent in Myanmar and 30 percent in Asia, even though there are promises of long-term returns of six to eight percent on Belt and Road infrastructure.[lvi] A more specific cautionary tale is that of the Chinese Wuhan province, where the local government has implemented a five-year subsidy programme to cover the losses of a state-run enterprise operating a Wuhan-Xinjiang-Europe container route.

Will political imperatives override the capacities of government to subsidise efforts of national entities brought into the initiative to participate? The kind of losses China expects to bear with its planned economic corridors in different regions underscores the need for INSTC member countries, who do not have the necessary deep pockets, to secure reliable funding on the grounds of strong financial merits. Focusing on the factors outlined in this section could go a long way in doing so.

Stopping the Buck at Economics

The above discussion illustrates that the INSTC is an economic project worthwhile pursuing, especially if it carves out a niche for itself in the long term as a transport corridor by diligently dealing with the above-identified factors.

The commercial consideration is of course only one part of the equation. There are, critically, security risks to be considered—whether in terms of a rise in militant activity in Afghanistan; the spread of the Islamic State eastward or local groups expressing affiliation; domestic political situations; or transborder crime, such as drug trafficking. These, incidentally, also weigh into the economics of the project, and thus its viability in the longer run. A comparative illustration is that of the railway from the Chinese city of Haimen to Hairatan, Afghanistan, that began plying in August 2016. The project has run into roadblocks: Uzbekistan is refusing to allow passage to Afghan goods on their way to China because of fears that the cargo trains could be used for drug trafficking, cementing criminal and terrorist elements in the area.[lvii] While the extent to which the security situation in Central Asia may endanger the functioning of the INSTC is beyond the scope of this paper, any conversation on the INSTC necessitates the recognition that it needs to tackle a broader question of tactics and strategies to deal with security theatres and threats. Will the INSTC adopt the approach that the Belt and Road Initiative has, of achieving internal security through development?[lviii] The situation on the ground, i.e., the specificity of the security challenges the INSTC faces, needs to be understood to better determine the cause-and-effect relationship between a development project, like the INSTC, and security. This, in turn, will help provide the way forward in terms of approach and managing spoilers.

Of greater pertinence to this paper’s focus on economics are the politics surrounding the INSTC. Proliferating connectivity projects can also advance geopolitical agendas. Nowhere is this clearer than China’s development of Pakistan’s Gwadar port in the Arabian Sea: as the first shipment from the deep-water port charted its course to the Middle East and Africa, experts noted[lix] that the port’s size and current cargo throughput will likely result in limited gains. Energy security is a key reason Beijing cited for pursuing this project, yet the medium-sized port’s capacity is insufficient to handle China’s annual demand for petroleum products. As one independent shipping industry analyst has point-blank stated, “Gwadar will not become China’s main trade hub with Persian Gulf countries, not to mention serve as an alternative route to the Malacca Straits.”[lx] Whether an economic logic exists or not―although its lack accentuates China’s geopolitical gambit―it is clear that, given the port’s location, a primary objective is for Beijing to gain a strategic foothold in the Indian Ocean.

For India, the advantages of using the INSTC are clear: access to Central Asian markets and resources that frees it from being dependent on its immediate neighbour Pakistan, with whom India has a fractious relationship. The Chabahar agreement signed between India, Iran and Afghanistan, which will connect, by rail, Chabahar to Zahedan in Iran and further on to Zaranj and Delaram in Afghanistan, not only provides India with direct access to Afghanistan where it has significant economic and security interests, but, when linked to the INSTC, suggests gains vis-à-vis regional ambitions, balance and stability. Afghanistan is integrated into the region, which fosters its development and links it to an alternative connectivity network that decreases its dependence on not only Pakistan (at the time of the signing of the agreement, Modi noted that “Afghanistan will get an assured, effective and a more friendly route to trade with the rest of the world”[lxi]) but also China. At the same time, it allows India to project its power via pursuing a project in the country that it can comfortably champion, with all its attendant costs. The Great Game in Mackinder’s Heartland remains an open theory; in the coming years, it will be critical for Indian interests that any power vacuum in the area not be filled only by China.

Geopolitical geometries that include China provide significant impetus for India to push forward its presence in the region via the INSTC. Given China’s rise and regional aspirations and what they mean for the balance of power in Asia and globally, the vagaries of India-China ties, warming China-Iran relations and the up-and-running Gwadar port (which provides China access to the western Indian Ocean, as noted earlier), are warning signals for many. The Gwadar port is thus often pitted against the Chabahar port, and the INSTC against the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and even China’s broader Belt and Road Initiative. As one commentator put it, “India’s humble but important version of China’s One Belt One Road plan.”[lxii] For some, regional connectivity is clearly another arena witnessing Sino-Indian competition―the “sleepy outpost” of Chabahar is often compared to not only China’s speedy implementation of the Gwadar port, but also Beijing’s expanding reach along the coastline with deals like the one signed to build and operate a container terminal in the UAE.[lxiii] The potential of Russia and Iran coming onboard the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor adds to the sense of competition. Thus the advocacy of pursuing the INSTC, linked to Chabahar port, as a geopolitical asset.

Ambition and geopolitical reasoning, however, will not be the fuel on which the multimodal transport corridor runs. Firstly, for India to be a player in Afghanistan and in Central Asia, it must have more than a token presence. That means getting the commercial aspects of the INSTC correct, which neither New Delhi nor any of the other stakeholders have the luxury of ignoring. Indeed, all parties to the INSTC have recognised the need to drum up private business interest to export along the corridor, and to provide an environment in which private sector players can interact. Secondly, China’s warming relationship with Iran need not be considered at the detriment of India-Iran ties. Some degree of perspicacity to keep things in balance will of course be necessary on New Delhi’s part, but not at the altar of zero-sum strategic reasoning. (Indeed, Iran calls Chabahar and Gwadar “sister ports,” and is interested in connecting the two. It has invited both Pakistan and China to be a part of the “not finished” Chabahar agreement. It would be wise to take another look at the extent Chabahar yields geopolitical benefit.) Likewise, the New Silk Road does not necessarily need to be at cross-purpose to the INSTC: it could effectively use some of the pathways that form part of the more expansive Chinese overland tranche. Taking advantage of the inevitable geographic complementarity makes both economic and logistical sense for India and other INSTC stakeholders (and may even advance a political détente between India and China). Gains beyond a narrow prism of geopolitics should be considered: first and foremost are the economic benefits to reap, if the factors laid out in the second section of this paper are assiduously dealt with.

One can also frame the INSTC amidst the larger, current global flux―owing in particular to dramatic, high-impact events that especially characterised 2016―which has introduced greater political uncertainty, and thus risk, into world politics. Recalibrations abound, whether actual, indicated, or called for. India, Iran and Russia coming together to develop the INSTC heralded a natural, common desire to take advantage of regional opportunity and multiply trade options and routes. Today, this venture faces politicking that calls into question what real leverage India stands to gain from being a stakeholder in the project.

The event of a Trump presidency has spawned several questions as to how the new US administration will handle ties with Iran and Russia. The more aggressive stance Trump seems to be taking vis-à-vis Iran (witness the fresh set of sanctions slapped on Iran following its failed medium-range ballistic missile test at the end of January) raises concerns about the future of the Iranian nuclear deal—and the impact it will have on Indian businesses and investments in Iran, particularly those staked in the Chabahar project. It would be pertinent to engage analysis on what the implications are if Chabahar is taken out of the conversation on the INSTC. Vis-à-vis Russia, a president who seems uncritical of Putin,[lxiv] and an unraveling of the Trans-Atlantic security alliance mean, for one, a strategic shift between Russia and the EU. Already, Russia’s ban on food imports from the EU increases the attractiveness for Indian foodgrains exports being delivered to Russia via the INSTC, but what does a changing Russia-EU equation mean for the INSTC developing links westward in the future? More critically, as India increasingly realises the need to be the torchbearer of democracy and liberal values in the current era of global shuffling, are there any reputational costs it may end up incurring with continued association with countries that may choose to play spoiler or disruptor in the region?

Political equations between the key INSTC stakeholders themselves also come into play as the international order evolves and multiple actors attempt to come into their own. Even as Russia and Iran find common strategic ground in the Middle East, Iran’s push to become a regional energy hub may not be seen benevolently by Russia, which has for years retained a monopoly as an energy supplier. The India-Russia relationship, too, is facing a reset, given Russia reaching out to China and Pakistan and India’s rapprochement with the United States. What does a China-Pakistan-Russia bonhomie mean for Afghanistan and the Central Asian space—and what consequences will it have on India’s advancement in the region? And to what extent will the INSTC be a pivot in these recalibrations?

The above questions need deliberation and analysis to ensure that a conducive political environment is fostered in which to not only pursue the INSTC but realise its full potential. But the fact remains that at the very least, enhancing trade ties and tapping new or underutilised markets remains a converging interest for all stakeholders. Pursuing the INSTC as an economic project, therefore, may be a smart move given the uncertainty surrounding the players, politics and the region. And it will make for a stronger case to continue using the transport corridor in the event India-Russia ties face a significant political setback, or Iran is put back into the proverbial international dog-house―to recall here is India’s defence of its continued, albeit limited, trade with Iran during the nuclear deal negotiations. (Indeed, a key imperative should be to strengthen direct banking channels between India and Iran to circumvent any future US sanctions that affect Indian economic engagement in Iran). As uncertain or unclear (geo)political gains appear for India, focusing on the economic known knowns and known unknowns of overland cross-border transport infrastructure—such as those delineated in this paper—should be the priority for India.

Endnotes

[i] “India to launch shipments to Russia via North-South Transport Corridor soon,” Sputnik, November 29, 2016, https://sputniknews.com/world/201611291047952232-india-iran-azerbaijan-railway/.

[ii] Kritika Suneja, “PSUs may be first to start shipment on International North-South Transport Corridor,” The Economic Times, December 13, 2016, http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/psus-may-be-first-to-start-shipment-on-international-north-south-transport-corridor/articleshow/55949783.cms.

[iii] “Iran-Azerbaijan Rail Linkup in a Month,” Financial Tribune, January 15, 2017, https://financialtribune.com/articles/economy-business-and-markets/57451/iran-azerbaijan-rail-linkup-in-a-month; Nigar Abbasova, “Date set for commissioning of Astara-Astara railway,” AzerNews, February 8, 2017, http://www.azernews.az/business/108582.html.

[iv] “Baku set to become major Eurasian hub,” Freight Week, October 1, 2016, http://www.freightweek.org/index.php/viewpoints-2/2258-baku-set-to-become-major-eurasia-hub.

[v] Dipanjan Roy Chaudhury, “Deutsche Bahn wants to use the INSTC to trade with Iran,“ The Economic Times, October 28, 2016, http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/foreign-trade/deutsche-bahn-wants-to-use-instc-to-trade-with-iran/articleshow/55109430.cms.

[vi] Boris Egorov, “Estonia interested in joining North-South Transport Corridor,” Russia & India Report, January 19, 2017, http://in.rbth.com/news/2017/01/19/estonia-interested-in-joining-north-south-transport-corridor_684316.

[vii] GIS Lab, IDSA.

[viii] “India to accede to the Ashgabat Agreement,” PM India, March 23, 2016, http://www.pmindia.gov.in/en/news_updates/india-to-accede-to-the-ashgabat-agreement/.

[ix] “Full text: India-Russia joint statement after PM Narendra Modi meets President Vladimir Putin,” NDTV, October 15, 2016, http://www.ndtv.com/india-news/full-text-india-russia-joint-statement-after-pm-narendra-modi-meets-president-vladimir-putin-1474578.

[x] R. Reiss, R. Gordon et al., “Integrated Corridor Management Phase I concept. Development and Foundational Research: Task 3.1 Develop Alternative Definitions,” US Department of Transportation, April 11, 2006, 2, https://ntl.bts.gov/lib/jpodocs/repts_te/14273_files/14273.pdf.

[xi] Michael Netzley, “The road to complication,” Dialogue Review, June 28, 2016, http://dialoguereview.com/road-complication/.

[xii] “Hitting the sweet spot: Middle class growth in emerging markets,” EY, April 25, 2013, http://www.ey.com/gl/en/issues/driving-growth/middle-class-growth-in-emerging-markets.

[xiii] Luo Yuanjun, “China’s rail freight goes international,” China Today, December 29, 2015, http://www.chinatoday.com.cn/english/lianghui/2015-12/29/content_713641.htm.

[xiv] Ksenia Zubacheva, “Moscow hosts academic conference on Russia-India relations,” Russia & India Report, February 21, 2017, http://in.rbth.com/politics/2017/02/21/moscow-hosts-academic-conference-on-russia-india-relations_706828.

[xv] Pritam Banerjee, “How to create a united Southern Asia,” The Diplomat, May 25, 2016, http://thediplomat.com/2016/05/how-to-create-a-united-southern-asia/.

[xvi] “International North South Transport Corridor (INSTC) Dry Run Report 2014,” Government of India and Federation of Freight Forwarders’ Association in India, http://commerce.nic.in/publications/INSTC_Dry_run_report_Final.pdf.

[xvii] David Rogers, “Iran’s railway revolution,” Global Construction Review, December 14, 2015, http://www.globalconstructionreview.com/markets/how-islamic-republic-set-become-land-br8i8d8ge/.

[xviii] “Prospects for Russian-Indian Cooperation for the Development of the “North-South” Transport Corridor” (presentation, India-Russia Think Tank Summit, Moscow, September 22 , 2016).

[xix] Spriha Srivastava, “China and Germany: A new special relationship?,” CNBC, August 10, 2016, http://www.cnbc.com/2016/08/10/china-germany-have-close-trade-and-investment-relationship.html.

[xx] “China’s new Silk Road to change global trade,” The Sunday Independent, March 12, 2017, https://www.pressreader.com/south-africa/the-sunday-independent/20170312/281891593077957.

[xxi] No such statistics were found by the author in her research.

[xxii] Lalatendu Mishra, “Move to make Nagpur a multi-modal logistics hub,” The Hindu, May 25, 2015, http://www.thehindu.com/business/Industry/maharashtra-government-decides-to-make-nagpur-a-multimodal-logistics-hub/article7244994.ece.

[xxiii] “INSTC Conference-India 2015 Report: Exploring opportunities on the INSTC,” Indian Ministry of Commerce & Industry and Federation of Freight Forwarders’ Association in India, 90, http://commerce.gov.in/writereaddata/uploadedfile/MOC_635986655921421162_INSTC_Conference_Report_Final.pdf.

[xxiv] “INSTC Conference-India 2015,” 89.

[xxv] “INSTC Conference-India 2015,” 52.

[xxvi] “Work on FTA between EAEU and India to begin in 2017,” Russia & India Report, September 16, 2016, http://in.rbth.com/economics/cooperation/2016/09/16/work-on-fta-between-eaec-and-india-to-begin-in-2017_630597.

[xxvii] China-Russia trade has surpassed $40 billion in 2016. “China-Russia trade to grow to @200bn – PM Medvedev,” RT, November 7, 2016, https://www.rt.com/business/365645-russia-china-minister-deals/.

[xxviii] “INSTC Conference-India 2015,” 77.

[xxix] Igor Zubkov, “SMEs to boost Russia-India economic cooperation,” Russia & India Report, May 16, 2016, http://in.rbth.com/economics/cooperation/2016/05/16/smes-to-boost-russia-india-economic-cooperation-tarasyuk_593399.

[xxx] See, for instance, Normaz Wana Ismail and Jamilah Mohd Mahyideen, “The Impact of Infrastructure on Trade and Economic Growth in Selected Economies in Asia,” ADBI Working Paper No. 553, December 2015, 16, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/177093/adbi-wp553.pdf.

[xxxi] Chu Daye, “Faster than shipping, cheaper than air flight, railway illustrates benefits of B&R initiative,” Global Times, May 16, 2016, http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/983333.shtml.

[xxxii] “The world this week,” The Economist, November 19-25, 2016, p.9.

[xxxiii] Wade Shepard, “Why the China-Europe ‘Silk Road’ Rail Network is Growing Fast,” Forbes, January 28, 2016, http://www.forbes.com/sites/wadeshepard/2016/01/28/why-china-europe-silk-road-rail-transport-is-growing-fast/#6dee0a357f24.

[xxxiv] “INSTC Conference-India 2015,” 76.

[xxxv] “ADB postpones issuance of funds for North-South project,” AzerNews, August 24, 2016, http://www.azernews.az/business/101299.html.

[xxxvi] “INSTC Conference-India 2015 report,” 45.

[xxxvii] Daye, “Faster than shipping, cheaper than air freight.”

[xxxviii] “INSTC Conference-India 2015,” 39.

[xxxix] Dhinesh Kallungal, “Vegetables from Kerala get an NOC to Europe,” The New Indian Express, January 4, 2017, http://www.newindianexpress.com/cities/kochi/2017/jan/04/vegetables-from-kerala-get-an-noc-to-europe-1555898.html.

[xl] Shepard, “Why the China-Europe ‘Silk Road’ Rail Network.”

[xli] “Statistics for India’s Trade with Russian Federation,” Embassy of India in Russia, http://indianembassy.ru/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=706&Itemid=706&lang=en.

[xlii] Asit Ranjan Mishra, “India looks to boost exports to Russia,” Live Mint, August 6, 2014, http://www.livemint.com/Politics/FlgXRq2sxEhfolQrXZtaiL/India-looks-to-boost-exports-to-Russia.html.

[xliii] Jonathan Matchett, “Cross-Border eCommerce in Russia – What you need to know,” Ecommerce Worldwide, September 7, 2016, https://www.ecommerceworldwide.com/expert-insights/expert-insights/cross-border-ecommerce-in-russia-what-you-need-to-know.

[xliv] Mitch Barns, “Global E-Commerce Becoming the Great Equalizer,” Forbes, January 20, 2016, http://www.forbes.com/sites/greatspeculations/2016/01/20/global-e-commerce-becoming-the-great-equalizer/#6e6de7625986.

[xlv] Graph prepared by author; data from Barns, “Global E-Commerce.”

[xlvi] Mishra, “Move to make Nagpur.”

[xlvii] James Conca, “Pick your poison for crude – pipeline, rail, truck or boat,” Forbes, April 26, 2014, http://www.forbes.com/sites/jamesconca/2014/04/26/pick-your-poison-for-crude-pipeline-rail-truck-or-boat/#e0227115777d.

[xlviii] “INSTC Conference-India 2015,” 14.

[xlix] “Evaluation of the EU-Turkey Customs Union,” World Bank Report No. 85830-TR, March 28, 2014, https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/pdf/financial_assistance/phare/evaluation/2014/20140403-evaluation-of-the-eu-turkey-customs-union.pdf.

[l] Ivan Tang, “China gets winning formula for silk road railway,” Seeking Alpha, March 30, 2016, http://seekingalpha.com/article/3961905-china-gets-winning-formula-silk-road-railway.

[li] “INSTC Conference-India 2015,” 44.

[lii] David Rogers, “Iran’s railway revolution,” Global Construction Review, December 14, 2015, http://www.globalconstructionreview.com/markets/how-islamic-republic-set-become-land-br8i8d8ge/.

[liii] Nigar Abbasova, “ADB postpones issuance of funds for North-South project,” AzerNews, August 24, 2016, http://www.azernews.az/business/101299.html.

[liv] Sachin Parashar, “Japan expresses interest in Chabahar, says no need to stay confined to India’s northeast,” The Times of India, September 8, 2016, http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/Japan-expresses-interest-in-Chabahar-says-no-need-to-stay-confined-to-Indias-northeast/articleshow/54159165.cms.

[lv] “India-Japan joint statement during the visit of Prime Minister to Japan,” Indian Ministry of External Affairs, November 11, 2016, http://mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/27599/IndiaJapan+Joint+Statement+during+the+visit+of+Prime+Minister+to+Japan.

[lvi] James Kynge, “How the Silk Road plans will be financed,” Financial Times, May 10, 2016, https://www.ft.com/content/e83ced94-0bd8-11e6-9456-444ab5211a2f.

[lvii] Jessica Donati and Ehsanullah Amiri, “Afghanistan struggles to access China’s New Silk Road,” Wall Street Journal, February 24, 2017.

[lviii] Xinhua, “Anti-terror fight needs comprehensive approaches: Chinese defense minister,” Chinese Ministry of National Defense, April 28, 2016, http://eng.mod.gov.cn/Database/Leadership/2016-04/28/content_4678356.htm.

[lix] Li Xuanmin, “Gwadar Port benefits to China limited,” Global Times, November 23, 2016, http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1019840.shtml.

[lx] Xuanmin, “Gwadar Port.”

[lxi] Elizabeth Roche, “India, Iran and Afghanistan ink trade corridor pact,” Live Mint, May 24, 2016, http://www.livemint.com/Politics/pI08kJsLuZLNFj0H8rW04N/India-commits-huge-investment-in-Chabahar.html.

[lxii] Manoj Joshi, “Relationship goals: In an America First world, pursuing an India First policy is the logical response,” The Times of India, February 4, 2017, http://blogs.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/toi-edit-page/relationship-goals-in-an-america-first-world-pursuing-an-india-first-policy-is-the-logical-response/.

[lxiii] Golnar Motevalli and Iain Marlow, “India slow to expand Iran port as China races ahead at rival hub,” Bloomberg, October 4, 2016, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-10-04/india-and-iran-slow-to-develop-port-as-china-builds-rival-hub.

[lxiv] As per Andrei Kozyrev, a former Russian foreign minister who now resides in the United States, “My fear is that this is probably the first time in my memory that it seems we have the same kind of people on both sides—in the Kremlin and in the White House. The same people. It’s probably why they like each other. It’s not a matter of policy, but it’s that they feel that they are alike. They care less for democracy and values, and more about personal success, however that is defined.” As quoted in Evan Osnos, David Remnick and Joshua Yaffa, “Trump, Putin and the New Cold War,” The New Yorker, March 6, 2017 issue, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/03/06/trump-putin-and-the-new-cold-war.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV