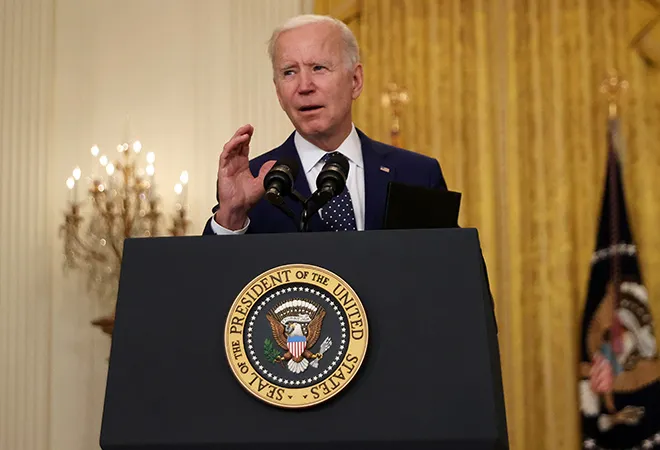

Barack Obama started making assertions about ending America’s “forever wars” during his Presidency. But it took two more Presidencies for the US to finally make the decision of ending America’s military footprint in Afghanistan. Asserting that the terror attacks of September 11, 2001, cannot justify American forces still dying in the nation’s longest war, Joe Biden announced last week the withdrawal of the remaining 2, 500 American forces by this September 11.

NATO simultaneously announced that the alliance would also be withdrawing its 7000 troops from Afghanistan. The Trump Administration’s peace deal with the Taliban signed last year had stipulated May 1 as the deadline for the full withdrawal but now the process will begin from May 1.

It had been clear for a very long time that the appetite in the US body politic for continued military engagement in Afghanistan was diminishing rapidly. Obama started the process but it was Trump who gave it momentum. Apart from Pentagon, there was a growing chorus of voices asking the US to pull troops out of an intractable conflict, which showed no real signs of closure.

In fact, when Biden was Vice President, he had pushed Obama to shift towards a small military profile with a focus on counterterrorism. Obama, at that time, had preferred to go in for the deployment of 17,000 additional troops to Afghanistan in 2009 to stabilise a deteriorating situation in Afghanistan, which he argued had “not received the strategic attention, direction and resources” it needed.

Yet after losing more than 2,200 US troops since 2001, with more than 20,000 having been wounded, and spending as much as $1 trillion, America’s patience with the Afghan war seems to have finally run out. Biden finally moved faster than his predecessors and ignoring the advice of his military command, decided that he would not go in even for a conditions-based withdrawal. He has learned from Obama and Trump who had tried but in the end were not able to fully break the link with Afghanistan.

The risks are obvious and have been talked about for quite some time. The US intelligence itself has warned of a complete collapse of the Afghan government and the Taliban accelerating their gains on the battlefield. Last year witnessed more Afghans getting killed by explosive devices than in any other country in the world even as the terrorist groups continue to operate and are resurgent, reveling in the ‘defeat’ of the mighty American forces. Despite all the challenges, democracy has begun to take root in Afghanistan, gains which can get obliterated now that there is no military power to back them up.

It is indeed ironical that the Taliban today are seemingly stronger than at any point since 2001 and the Afghan government perhaps at its weakest. Washington is suggesting that some American troops will continue to remain in Afghanistan and special operations forces working on counter-terrorism missions would remain active but their numbers remain in the realm of speculation.

American policymakers are aware of critical intelligence emanating from this part of the world and they would like to continue to maintain an intelligence presence to ensure that Al Qaeda and similar terror groups do not, once again, spring a surprise. But how this posture will be integrated within the emerging political structures in Afghanistan is not readily evident at this juncture.

Not surprisingly, talks of an impending civil war in an already war-infested nation are the order of the day. There is no real incentive for the Taliban to concede on any issue given that Washington's best bargaining chip—its military prowess—is now off the table. In their response, the Taliban asserted that the “American officials have understood the Afghan situation” but as the withdrawal had been put off “by several months” it’s a violation of the Doha accord.

As such, the American side “will be held responsible for all future consequences, and not the Islamic Emirate.” The Taliban also announced that “until all foreign forces completely withdraw from our homeland, the Islamic Emirate will not participate in any conference that shall make decisions about Afghanistan.”

This was in reference to the conference being hosted by Turkey, Qatar, and the United Nations in Istanbul on 24 April. This is perhaps the last-ditch effort to revise the peace process and to ensure that regional stakeholders are embedded in the larger effort to bring some semblance of stability to Afghanistan.

Though Biden administration insists it wants to see an orderly transition, its abrupt decision has created more uncertainty for regional players. It can now only be hoped that this new withdrawal timeline serves as a catalyst for Afghan stakeholders to reach a political settlement by September. The consequences of not reaching such a settlement could be quite high for the people of Afghanistan and the entire region.

Some wars never end, they just morph into something different in tone, tenor and content. Afghanistan has seen much turmoil in the past and the future offers no guarantee of any redemption. It’s now up to ordinary Afghans and their supporters who believe in a better world for the next generation of Afghans to rise up to the challenge and ensure that a Talibanised version of Afghanistan is not the only one that the world encounters in the future. And in this, India will have to play an important role. The crutches of the American military are going and a new sense of purpose will be needed in New Delhi.

This commentary originally appeared in CNBC TV18

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV