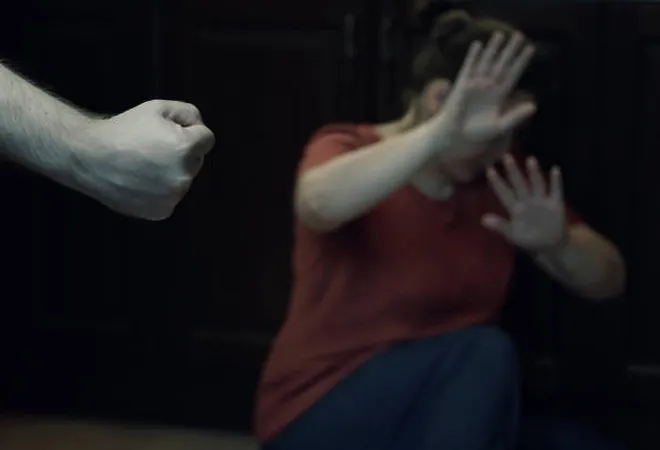

Gender-based violence (GBV) or violence against women and girls is regarded as a global pandemic that affects one in every three women across their lifetime. An estimated 736 million women become victims of intimate partner violence (IPV), or non-partner sexual violence, or both, at least once in their life. The international community has long acknowledged the severity of the problem. In 1995, the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action called for the elimination of violence against women. A decade later, in 2015, the UN adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development which included a global target to eliminate “all forms of violence against women and girls in public and private spheres.”

The international community has long acknowledged the severity of the problem. In 1995, the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action called for the elimination of violence against women.

In 2016, the World Health Assembly Resolution 69 called for a global plan of action to strengthen the role of the health system within a national multi-sector response to address interpersonal violence, particularly against women and young girls. Despite all these mandates, however, 49 countries have yet to adopt a formal policy on domestic violence. This violence—which has serious short- and long-term consequences on women’s health and well-being—disproportionately affects women in low- and lower-middle-income countries.

Women aged 15-49 years living in the least developed countries have a 37% lifetime prevalence of domestic violence. Among younger women (15-24), the risk is even higher, with one of every four women who have ever been in a relationship facing some form of violence. Indeed, domestic violence is an all-pervasive public-health concern that women face in various forms across different parts of the world. In England, for example, the 2020 Crime Survey reported a 9% increase from 2019 in domestic-abuse related crimes.9 In the United States (US), the number of women who have ever reported experiencing domestic violence increased by 42% from 2016. The 1993 United Nations Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women defines ‘gender-based violence’ as “an act that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual, or psychological harm or suffering to women (including threats of such acts), or coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or private life.”

In India, 30% of women have experienced domestic violence at least once from when they were aged and around 4% of ever-pregnant women have experienced spousal violence during a pregnancy.

The focus of this paper is Domestic Violence—the most common form of GBV against women. This paper defines ‘domestic violence’ as any form of violence (physical, sexual, psychological and verbal) against women in a domestic setting of a marital home or, within an intimate relationship, that results in or is likely to result in physical or mental harm or suffering to, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or private life. It is often used interchangeably with IPV. In India, 30% of women have experienced domestic violence at least once from when they were aged and around 4% of ever-pregnant women have experienced spousal violence during a pregnancy. This paper studies the link between domestic violence and women’s sexual and reproductive health, across their life course. Existing literature point to a significant association between domestic violence, and the poor health and well-being of not only the women themselves, but the children they give birth to, and are expected by social norms to care for. Indeed, the impacts of violence against women lead to grave demographic consequences, including low educational attainment and reduced earning potential for the younger generations.

A 2017 study of India, Nepal, and Bangladesh found GBV to be a risk factor for unintended pregnancies among adolescent and young adult married women. Studies from different countries have also suggested moderate to strong positive associations between IPV and clinical depression. These analyses noted an increased risk of 2-3-fold in depressive disorders and 1.5- 2-fold increased risk of elevated depressive symptoms and post-partum depression among women who have been subjected to intimate-partner violence. These women reported more episodes of anxiety and depression, and increased risk of low birth weight babies, pre-term delivery, and neonatal deaths.

Studies from Bangladesh and Nepal show the association between violence and women’s poor nutritional status, increased stress, and poor self-care.

In one 2005 study, South Asian women in the US reported that domestic violence reduced their sexual autonomy and increased their risk for unintended pregnancy; many suffered abortions. A recent review of women from the US, India, Brazil, Tanzania, Spain, Sweden, Norway, Australia and Hong Kong found that domestic violence was associated with an increased risk of shortened duration of breastfeeding. Studies from Bangladesh and Nepal show the association between violence and women’s poor nutritional status, increased stress, and poor self-care. Also in Bangladesh, demographic health surveys show compromised growth in children born to women suffering domestic violence. In India, domestic violence has been found to impact early childhood growth and nutrition. Another analysis of data from Pakistan showed a significant increase in underweight, stunting, and wasting among children of women subjected to domestic violence. There is no dearth, therefore, in evidence that shows a direct causal relationship between domestic violence and the growth and development of children.

This commentary originally appeared in Hindustan Times.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV