Introduction

Competition policy in the West is shifting from a deliberative, evidence-based, ex-post approach to a form that is more presumptive, pre-emptive, and ex-ante. The European Union’s (EU) Digital Markets Act (DMA), for example, aims to make the “digital sector open and contestable”.[1] It places a set of negative and positive obligations on entities designated as “gatekeepers”, defined in the DMA as companies that have significant market influence as well a defined threshold of turnover or users. The restrictions on such entities include bars on targeted advertising and the use of personal data gathered from one platform to offer services on another.[2] A gatekeeper therefore would be barred from using data mined from its browsing service for targeted ads on social media or other ad-supported products.[3] These prohibitions work on the assumption that large digital businesses enjoy entrenched positions because they create “conglomerate ecosystems around their core platform services, which reinforces existing entry barriers” and can result in “unfair” conduct.[4]

In the United States (US), too, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is emphasising ex-ante measures to safeguard competition by restoring a policy of restriction acquisitions for entities that pursue “anti-competitive mergers”.[5] In July 2021, the FTC voted to repeal a 1995 Policy Statement that ended prior notice and approval requirements in the Commission’s merger orders. The repeal restores the Commission’s ability to investigate and prevent mergers that are prima-facie anti-competitive.[6] The Western narrative on competition policy is thus clear: Big is bad, and steps must be taken to mitigate the harms of “bigness” to the economy and society.

The case of emerging economies like India is different, as they are yet to establish a firm stance on competition policy in digital markets. On the one hand, bodies charged with the oversight of competition governance generally favour a less interventionist approach. In 2019, the Competition Law Review Committee (CLRC) issued recommendations to bolster competition frameworks and governance in India, particularly in the context of digital markets.[7] The CLRC found that the existing provisions in the Competition Act, 2002 were largely adequate to deal with a majority of the technology-related challenges to competition. The CLRC recommended amending Section 3(3), which identifies certain conduct as inherently anti-competitive when carried out through horizontal arrangements, to impute strict liability on hub-and-spoke business models if they engage in any of the same activities.[8] However, there were no overtures to the introduction of additional ex-ante enforcement measures beyond revisions to existing provisions regarding merger control.

At the same time, certain Government departments and bodies are increasingly gravitating towards pre-emptive and prescriptive competition regulation. For instance, the Department of Consumer Affairs proposed amendments to the Consumer Protection (E-Commerce) Rules, 2020 that included prohibitions on “flash sales” and increased regulatory burden on e-commerce entities—the aim was to level the playing field with brick-and-mortar retailers. The Rules were not notified and various government agencies publicly criticised the provisions. The Parliamentary Committee on Commerce, for example, stated that the blanket obligations proposed by the Rules would adversely affect Indian start-ups.[9]

More recently, in 2022, the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Commerce recommended identifying “gatekeeper” e-commerce platforms that require stricter oversight.[10] The suggestion comes on the heels of increased complaints about both global and local e-commerce platforms and their roles in different digital markets. There is little doubt that it is influenced by the DMA.

It is in this broad context that the Esya Centre and the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) convened a discussion among stakeholders belonging to the public sector, industry, academia, and consumer interest organisations as a first step towards formulating a position on digital competition regulation for India. The discussion was the first in what Esya and ORF envision as a series of discussions on a complex subject that requires multiple rounds of debate in a multi-disciplinary context. This report is a synthesis of the insights that were shared during the discussion. The report may appear to be asking more questions than it answers—and that is by design. The aim is to provoke thinking around competition regulation in digital markets in order to trigger responses and build a collective impetus towards solutions. Therefore, the report refrains from creating biases in readers’ minds in favour of particular solutions, as that would only narrow the scope of thinking devoted to finding answers to the problems posed.

The discussion was divided into four sessions, each focusing on an aspect of emerging approaches to digital competition regulation. This report follows the same outline and unbundles key elements of the debates around the new approach to competition practice. It considers the broader context of competition in India and how a more interventionist competition regime could play out in the country.

Part 1 discusses the merits and demerits of relying on non-price factors in competition assessments. Part 2 delves into the possible trade-offs and advantages of data determinism. Part 3 assesses the feasibility of applying utilities-style regulation to digital businesses. Finally, Part 4 outlines the various competitive dimensions that arise in the Indian digital market and tests some of the presumptions that back the adoption of DMA-style regulation in the country.

I: Non-Price Factors in Competition Determinations

A key element of the new Western approach to competition policy and practice is the shift away from traditional standards of competition assessment, such as consumer welfare and price-based competition, towards increased emphasis on non-price factors.[11] The argument for increased reliance on non-price factors is that many digital businesses are free (or low-cost) because they have innovative business models or proffer high efficiencies. These factors ostensibly render existing standards for price-based competition such as consumer welfare, typically considered in terms of lower prices by courts, obsolete.[12] Proponents of greater reliance on non-price factors such as Lina Khan, current Chair of the US FTC, argue that continued dependence on consumer welfare may confound enforcement efforts, as the generation of surpluses is seemingly inherent to digital business models.[13] Specifically, Khan contends that it could create situations where harms to competition may be left unchecked. Therefore, it is argued that standards for competition assessment must move away from price (and price-related welfare calculations) that may be more relevant to the digital realm.

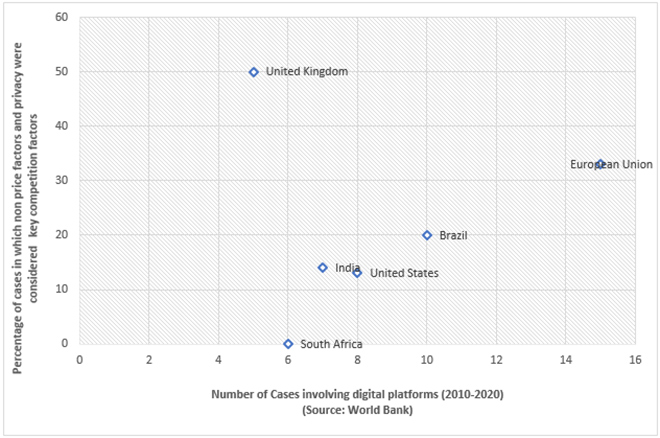

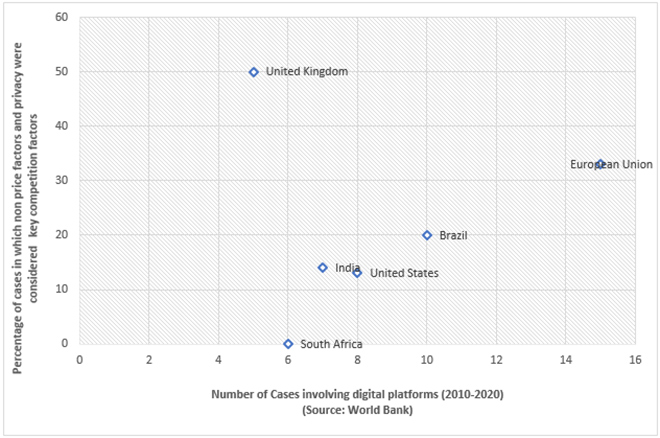

A perusal of global competition cases reveals an interesting divergence between European jurisdictions and emerging economies on the issue of relying on non-price factors in competition cases. European jurisdictions are decidedly in favour of bringing in non-price factors in competition determinations; meanwhile, developing nations such as India, Brazil and South Africa have adopted a more conservative approach, with competition authorities considering non-price factors in a low 13-20 percent of cases involving digital platforms (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 also illustrates how, in the United States, courts have paid little heed to non-price factors in competition assessments over the last decade. Conversely, the FTC has increased its emphasis on reliance on non-price factors. In January 2022, the FTC and the US Justice Department announced that they are revising merger guidelines to give greater emphasis to non-price competition in market definition analyses.[14] This indicates that there may be an emerging difference between US courts and the competition regulator on the necessity of non-price factors in competition evaluations.

Figure 1. The Role of Non-Price Factors in Cases Involving Digital Platforms (2010-2020)

Non-price factors are not a novel concept. In telecommunications, for instance, Quality of Service (QoS) standards play an important role in determining “the degree of user satisfaction.”[15] However, what constitutes QoS in telecom is well-established and easily quantifiable. For instance, there are established parameters for calculating dropped-call rates in telecom services—although even these can be contentious.[16] Conversely, non-price factors relied on for competition assessments in digital markets can be qualitative and subjective. For instance, the FTC considers the effect of a merger on innovation in terms of whether the merged firm is able to conduct research and development more effectively.[17] Such a standard is likely to be discretionary, particularly as the trajectory of innovation is unpredictable. The question is whether standards can be established to lend greater objectivity in non-price determinations.

Another emerging consideration regarding the reliance on non-price factors in competition assessments is the movement by competition authorities into distinct areas of law, such as privacy. In such cases of jurisdictional overlap, where should the oversight of one authority, say in the case of privacy, the Data Protection Authority, end, and that of the competition regulator’s begin? One way to move forward is to understand whether curtailments of privacy arise as a consequence of a firm’s dominant position in a market. For instance, if a firm takes a decision that impacts user privacy negatively, and users are left with a take-it-or-leave-it scenario because they have limited ability to switch to a comparable competitor—there could be a case for evaluating whether this qualifies as an abuse of dominance. However, the threshold for privacy would still have to be determined. In such matters, questions of institutional capacity arise. Would the competition regulator look into a mere erosion of privacy or would there be a standard that it would establish about how much privacy is “enough”? In the absence of privacy legislation, what would it look to for guidance? Could this lead to inconsistent and discretionary competition jurisprudence?

Is there, then, a case to be made to build the capacity of competition regulators so that they are better equipped to grapple with such matters? At the same time, in an area of law that is constantly evolving, would such capacity-building measures need to continue to update and apprise regulators of standards being followed and established globally? More importantly, will capacity-building efforts also look into efficacy of interventions in ushering in both greater competition as well as value for consumer in digital markets?

An extension of capacity building is the creation of standards for the assessments relying on non-price factors. Are there elements that can be sufficiently quantified to limit subjectivity? Would these formulae hold in the face of a dynamic and fluid digital market? Who should initiate the process of standard setting – should academics, industry, regulators, or a combination of all be involved?

II: The Trade-offs of Data Determinism

‘Data determinism’ is the notion that data is the be-all and end-all of comparative advantage in the digital economy. More customers translate into more data, which allows for greater product optimisation and service delivery, sparking a virtuous cycle towards increase in scale and commercial success. Data determinism typically forms the basis for arguments that favour ex-ante competition regulation of digital markets. The argument is buoyed on narratives surrounding the importance of access to data to increase national competitiveness and prosperity. Specifically, proponents of data determinism argue that control over data by large technology platforms harms competition in digital markets as it can operate as a barrier to entry and stifle innovation. As such, it is argued that the alleged hegemony these companies have over data must be upended and channels of access to such data be created.

Network effects are typically strong in digital products and services.[18] The strong demand-side economies of scale of networked businesses means that their value is directly proportional to the number of users they have.[19] Network effects are amplified by a phenomenon known as “positive feedback”: as more consumers use a certain product, many others are motivated to do the same. Data determinism, in a sense, is a function of a deterministic outlook on these fundamental aspects of information businesses.

An example of data determinism in practice is the Draft National E-Commerce Policy 2019 which argues that data is “the most critical factor in the success of an enterprise.” It further notes that “the presence of ‘network effects’ means that in the era of data, the larger the firm, the greater the access to potential sources of data and greater the likelihood of its success.”[20]

However, the interplay of networks/information businesses and data are complex. For instance, let us consider data collection. Proponents of data determinism may argue that data collection results in entry barriers because “some data is created as a result of distinctive interactions.”[21] However, data is non-rivalrous, i.e., it can be consumed by multiple entities or individuals at the same time. As such, an entity looking to collect data for its own specialised needs can do so.[22]

Carl Shapiro (1999) points out that “innovation is king in digital markets…No company can afford to stand still, whether it designs microprocessors for computers, writes software, offers communications services, or creates information content. Failure to seize opportunities for innovation is likely to be fatal.”[23] If the market desires a product, consumers will flock to it, even if there is a dominant entity in that market. Thus, seemingly entrenched digital monopolies can be dislodged if consumers are given the choice of a better product or service.[24]

For example, Facebook is considered by many competition authorities across the world to be dominant in the social media market. The US FTC, for instance, filed a case against Facebook in 2020 for illegal monopolisation.[25] Yet, in 2021, the social media application TikTok unseated Facebook as the world’s most downloaded application.[26] Facebook is attempting to emulate TikTok through a feature known as “Reels” which allows users to post short-form videos—a format pioneered by TikTok.[27] But emulation does not always translate into success. When TikTok was banned in India in 2020, a host of domestic imitators cropped up. Two years on, not one of these Indian apps has been able to garner the same kind of popularity.[28] To be sure, it remains to be seen whether Facebook’s ‘Reels’ gambit will pay off. These examples—of TikTok countering Facebook’s dominance in social media as well as the inability of Indian TikTok imitators to bring out a viable substitute—illustrate that the course of data markets is anything but deterministic.

A more fundamental consideration is that raw data has nominal innate value, and it is the insights drawn from data that generate revenue. These analytic capabilities are typically in the form of software that has a number of intellectual property (IP) protections. IP considerations surrounding data must be upheld, not just because India is beholden to do so by both national and international legal instruments. The erosion of intellectual property creates a disincentive to invest in “data-driven innovation”.[29]

In India, both databases and software are protected under the Copyright Act, 1957. India is also a signatory to several treaties that affirm the protection of software and databases under copyright but extend trade secret protection to it as well, such as the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property (TRIPS) and the WIPO Copyright Treaty (WCT). Article 10.2 of the TRIPS agreement, accords protection to “compilations of data which by reason of selection or arrangement of their contents constitute intellectual creations.”[30] Importantly, while such protection does “not extend to the data itself”, it is “without prejudice to any other copyright” that may accrue to such data.[31] Article 5 of the WCT accords the same protection to databases. Finally, Section 2(o) of the Copyright Act, 1957 accords protection to databases as literary works. It grants authors/owners of such databases the exclusive right to, among other things, reproduce these works.

The protection afforded to databases under the Copyright Act, 1957 has been elaborated upon in court cases. Two doctrines, the “sweat of the brow” and “modicum of creativity”, broadly govern this protection.[32] For a database to be “copyrightable” there should have been investment or labour of some kind to put it together, as well as a “minimum level of creativity”.[33] The creativity doctrine has been used in the past to deny protection to “copy-edited judgments”.[34] However, it is uncertain whether there could be a similar denial to databases created by digital platforms algorithmically. As pointed out earlier, data collected by platforms is a function of the specific interaction between the service offered and the data subject. As such, it can be said that the database is the outcome of creativity, namely the creation of algorithms and/or a unique platform service. At the very least, it is likely that any attempt to appropriate such database through a law or other measure, will be challenged before the courts.

In addition, it is likely that there will be numerous bilateral obligations regarding the safeguarding of IP related to datasets and other intangible property in the numerous free trade agreements that India is negotiating with different countries. For instance, the United Kingdom (UK) has made clear that it will resist any provisions that undermine high standards of IP protection.[35]

What follows is that there is very little that is deterministic about data markets, least of all outcomes where data is either taken from competitors or products are reverse-engineered and put into the market when competitors have been shut out. Moreover, those who support data determinism tend to overlook the fact that there are multiple segments of digital markets where Indian companies control a majority of the data flows, such as online booking and food delivery. Any attempts to appropriate data in the name of development would necessarily have an adverse impact on these companies as well. It may then be useful to take a step back and understand what it is we really seek when we talk about access to data, and frame those objectives in the larger context of international trade and domestic commerce.

III: Should Digital Platforms Be Regulated as Utilities?

Inherent to the notion of the platform as a gatekeeper is the premise of the platform as a digital utility. The natural corollary is to impose utilities-style regulation on these businesses. Article 6 of the DMA, for instance, requires gatekeeper platforms to interoperate with application stores on mobile operating software, to give both users and developers greater choice.[36] But are these platforms really utilities and what are the possible consequences of treating them as such?

Guggenberger (2021) argues that “digital platforms are railroads for the modern era.” Citing the examples of the largest players in internet search, e-commerce, social media, and app stores, Guggenberger notes that these platforms will on the one hand, “create and curate markets” by “providing infrastructure” and creating guidelines by which participants must abide. At the same time, they will participate in these markets and compete with “third-party vendors”, which can place the latter at considerable disadvantage. Thus, Guggenberger recommends that the “essential facilities doctrine” be applied to these companies and compel them to provide fair and equitable access for business users to their platforms.[37]

Lipsky (2020) cites Justice Stephen Breyer’s remarks in the matter of AT&T Corp. v. Iowa Utilities Bd, to make arguments against the application of the essential facilities doctrine to large digital companies. In that case, Justice Breyer noted, there is no “guarantee that firms will undertake the investment necessary to produce complex technological innovations knowing that any competitive advantage deriving from those innovations will be dissipated by the sharing requirement.”[38] Thus, forced sharing creates a disincentive for firms to innovate and invest in the upkeep of their platforms. Breyer also noted that it is likely that forced access to such platforms or unbundling will result in higher costs—and in such cases, who is expected to bear that burden? In all likelihood it will be the consumer. Lipsky concludes that “increased sharing does not automatically translated into increased competition.”[39]

It could also be argued, however, that using regulation to disrupt bottlenecks essentially forces platforms to compete. However, competition is not the same as forced access. Indeed, by compelling access, the regulator—as Justice Breyer noted—is directly obstructing the platform’s ability to compete.[40] The EU DMA, for example, prohibits gatekeeper entities to use the data of businesses on their platforms when competing with the latter.

One report by Struble (2017) noted that the hallmark of public utilities is a lack of competition.[41] Struble argued that while certain digital markets might be marked by concentration, “they do not fit the public-utility model, because real competition is possible.”[42] Struble also observed that the “utility model denies that possibility” because it cedes “dominance to a single firm” and precludes the possibility of future competition.[43]

Another aspect of the digital public utilities contention is that it contradicts the position in Indian competition law. The imposition of utilities-style regulation on digital platforms sends a signal that dominance is per se anti-competitive. In contrast, Section 4 of the Competition Act, 2002, recognises that it is the abuse of dominance, and not dominance itself, that is antithetical or harmful to competition. Notably, the current “per se” standard in the Competition Act, 2002, as applicable to horizontal agreements, is not absolute.

There are many ways in which utilities-style regulation can be applied to large digital firms. There are the principles of interconnection or interoperability and platform neutrality which can be found in multiple obligations of the EU DMA. In India, however, there have been instances where regulators have suggested a more direct imposition of utilities frameworks to new digital businesses. However, these contentions are framed in terms of levelling the field between legacy utilities operators and their allegedly new digital avatars. In 2018, for example, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) issued a consultation considering the application of telecommunications licensing and regulations to communications over-the-top (OTT) applications.[44] The arguments presented by the regulator in favour of the move was that communications applications were placing competitive pressures on telecommunications service providers (TSP) without having to deal with the burden of regulation and license fees. In its recommendations, however, the TRAI ultimately concluded that the imposition of licensing was unnecessary.[45] The TSP services and OTT services were not substitutable and communications OTTs drove a lot of investment and consumer demand for data for TSPs.

It is uncertain how the imposition of a telecommunications licensing framework on communications OTT services would: one, benefit consumers; two, benefit competition; and three, be implementable. How would a communications OTT fulfil universal service obligations in areas that do not have proper internet penetration? Finally, as was alluded to by Justice Breyer’s arguments about the increased cost of forced access or greater regulatory compliance, on whom will such costs devolve? And if regulators do not want costs to rise, will they bring in price regulation? If so, how would such price regulation impact innovation and efficiency?

IV: Contextualising Competition in India: Multi-Dimensionality and Competitiveness

Competition issues in India are multi-dimensional and, thus, require a holistic assessment of the considerations at play. First, there is the issue of legacy industries pushing for the institution of a regulatory level playing field against their digital counterparts. For instance, in the wake of COVID-19, film producers started taking their movies directly to digital platforms as theatres were indefinitely shut. Many theatres owners’ associations responded with strong statements of disappointment, and even boycotts in some instances. The Kerala Theatre Owners Association took a decision to boycott the movies of actor and producer Salman Dulquer because he released a movie on a digital platform. The movie was slated to be released in theatres in January, but closures prompted by a COVID-19 outbreak prompted Dulquer to opt for an online release.

Second are the frictions between stakeholders in value chains that lead to competition litigation and complaints to decision-makers. These include battles between app store controllers and developers, marketplace platforms and sellers, restaurants, and food delivery applications—the list is long. It is uncertain, in such circumstances, whether complainants are coming forward to gain greater leverage in negotiations or whether there is a legitimate unfair trade practice at play.

Such scenarios prompt the introduction of legislations such as the DMA that seek to pre-empt the alleged harms carried out by gatekeepers, ostensibly by preventing the platform that connects a business to its customers (i.e. the gatekeeper) from engaging in unfair trade practices. The problem here, of course, is that it is unknown how platforms will adapt to such legislation. Most may welcome it, as it would entrench their position by raising a barrier to entry that makes it harder for new entrants to come into the market. It could also raise prices for consumers and deny them certain efficiencies that come along with the cross-pollination of services. Lastly, the imposition of static regulation is likely to create friction with dynamic and fast-evolving digital markets.

The larger point is that the resolution of such issues is complex and cannot be resolved by ad-hoc interventionism. Legislative outcomes are always uncertain, particularly in an unpredictable and dynamic digital realm. More importantly, competition is not a function of competition doctrines alone. There are several frameworks that play indirect roles in determining a firm’s competitiveness in the domestic market. For instance, foreign direct investment (FDI) restrictions necessarily make it harder for younger firms to compete with larger conglomerates, because the former have greater dependency on FDI. These matters require considered deliberation over a period of time.

For those that contend that the fast pace of the digital world requires imminent action to prevent irreversible harm, it is also important to consider the fact that ex-ante remedies can be implemented ex-post as well. Illustratively, Section 33 of the Competition Act, 2002 empowers the CCI to grant interim injunctions in certain circumstances. While the power is used sparingly, it was recently deployed in the matter of Federation of Hotel and Restaurant Associations and Casa2 Stays Pvt. Ltd. vs. MakeMyTrip India Pvt. Ltd. & Ors (GoIbibo and OYO) (see Box 1). Thus, it is possible to take ex-post action to pre-empt possible competition harms as well.[46]

Box 1. Case Study: Use of Interim Injunction to Pre-Empt Harms to Competition in Digital Markets

|

Federation of Hotel and Restaurant Associations and Casa2 Stays Pvt. Ltd. (Fabhotels) vs. MakeMyTrip India Pvt. Ltd. & Ors

with

Rubtub Solutions Pvt. Ltd. (Treebo) Vs. MakeMyTrip India Pvt. Ltd. and Oravel Stays Private Limited (OYO)

Fab Hotels, a chain of 3-star budget hotels and Treebo, an online hotel booking service, made a prayer to the Competition Commission of India under Section 33 of the Competition Act, 2002, to direct MakeMyTrip (MMT) and Go-Ibibo (hereinafter MMT-Go), a set of online travel aggregators had recently merged, to re-list their properties on the latters’ portals. Fab Hotels and Treebo alleged that MMT-Go denied them market access as they refused to pay the high commission fees allegedly demanded by the latter. They also alleged that MMT-Go gave preferential treatment to OYO, another network of budget hotels, due to a deal MMT-Go entered with the latter.

The Competition Commission of India found that MMT-Go did, indeed, have an exclusive arrangement with OYO because of which Treebo and FabHotels (budget chains that were OYO’s competitors) were delisted from the platforms. The CCI granted Treebo and FabHotels interim relief and ordered MMT-Go to relist them.

|

What stands in favor of interim injunctions rather than rigid, ex-ante prohibitions is the strong evidentiary standard for the former. The evidentiary standard for interim injunctions under Section 33 of the Competition Act, 2002 was established by the Supreme Court in the matter of the Competition Commission of India v. Steel Authority of India Ltd. In that case, it was the Supreme Court held that the CCI may grant an interim injunction if:[47]

- if it is proved to the satisfaction of the Commission that there is an agreement or a prospective merger that may have an appreciable adverse effect on competition, or there has been some abuse of dominance;

- it is necessary to issue an order of restraint;

- it is clear that there is a high likelihood that the litigating party will suffer irreparable and irretrievable damage or there is certainty that there would be an adverse effect on competition in the market.

These facts are brought out through the process of enquiry and perhaps this sets out a more flexible and reasonable approach than a blanket restriction.

Alongside the dynamics of competition in India is the story of competitiveness. The EU’s competition policies have come under criticism lately for possibly hampering European competitiveness. In 2019, the European Commission blocked a merger between Germany’s Siemens and France’s Alstom as it may harm competition in “railway signaling systems and high-speed rail.”[48] The decision was heavily criticised because it may have hurt Europe’s chance of creating a national champion in rail that could challenge CRRC, a Chinese rail “behemoth”, in the global market.[49] Economist Elie Cohen noted that the merger created an entity that was better able to challenge the CRRC in a high-speed rail market that was largely global.[50]

To put matters in perspective, Cohen noted, “where Alstom and Siemens are fighting to share an annual production of 35 TGVs per year, CRRC makes 230! Where the European high-speed market is stagnating, China has just launched an additional $125 billion investment plan to build 3,200 km of TGV lines in addition to a 25,000 km network!”[51] Cohen also concluded that, in this instance, competition would have hurt the prospects of the two European rail companies to compete, and their complementarities created the base for a more “balanced group with diversified income.”[52]

As a response to the Alstom decision, Germany and France issued the “Franco-German Manifesto for a European Industrial Policy fit for the 21st Century”. The Manifesto called for, among others, a revision of competition rules to ensure that industrial policy decisions are given due consideration in determinations.[53]

The example of high-speed rail is useful in the context of digital markets because they are also global. Here again, the European countries lag considerably behind. Of the top 50 technology companies by market capitalisation, only five are European, and only two of these are software companies (SAP and Booking.com).[54] If India is looking to enable its start-ups to establish a global footprint, is the European template the right one to follow?

The example of the Alstom-Siemens merger highlights the importance of whole-of-government approaches when implementing competition policy and regulation. Decisions related to competition must be considered against the backdrop of trade policy to evaluate how they stack up against India’s global commitments, and may affect market access, and competitiveness. Similarly, consideration must be given to how different aspects of industrial policy may impact both competition and competitiveness.

Conclusion

As the Introduction to this report made clear, this analysis seeks to pose questions rather than offer solutions in an attempt to start a conversation that engages with the complexity of competitive dynamics set in the unique context of India. The report aims to prompt deeper engagement with these questions in future discussions around the subject.

While it is easy enough to take a firm stance on digital competition issues—and indeed in many instances it may be warranted—it is necessary to delve into the mechanics of what such a position could look like. India must consider all dimensions of the debate as it crafts its own position on the issue.

Endnotes

[1] ‘Questions and Answers: Digital Markets Act: Ensuring Fair and Open Digital Markets’, European Commission – European Commission (European Commission, 23 April 2022).

[2] Wall, Colin. ‘The European Union’s Digital Markets Act: A Primer’ (Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2 August 2022).

[3] Wall, Colin. ‘The European Union’s Digital Markets Act: A Primer’.

[4] ‘Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Contestable and Fair Markets in the Digital Sector (Digital Markets Act)’ (European Commission, 15 December 2020).

[5] Federal Trade Commission. ‘FTC to Restrict Future Acquisitions for Firms That Pursue Anticompetitive Mergers’, 25 October 2021.

[6] ‘Statement of the Commission on Use of Prior Approval Provisions in Merger Orders’ (Federal Trade Commission, 25 October 2021).

[7] Srinivas, Injeti, Ashok Kumar Gupta, Pallavi Shardul Shroff, M.S. Sahoo, Haigreve Khaitan, Harsha Vardhana Singh, S. Chakravarthy, Anand Pathak, Aditya Bhattacharjea, and KVS Murty. ‘Report Of Competition Law Review Committee’. Ministry of Corporate Affairs, July 2019.

[8] Srinivas, Injeti, Ashok Kumar Gupta, Pallavi Shardul Shroff, M.S. Sahoo, Haigreve Khaitan, Harsha Vardhana Singh, S. Chakravarthy, Anand Pathak, Aditya Bhattacharjea, and KVS Murty. ‘Report Of Competition Law Review Committee’.

[9] Vijayasai Reddy et al., ‘Promotion and Regulation of E-Commerce in India’ (Department Related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Commerce, n.d.).

[10] Moneycontrol. ‘Parliamentary Committee Suggests Identifying “Gatekeeper” e-Commerce Platforms’. Accessed 19 October 2022.

[11] Please see Khan, Lina M.. “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox.” Yale Law Yournal 126 , no. 3 (2017): 564–907.

[12] Khan, Lina M.. “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox.”

[13] Khan, Lina M.. “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox.”

[14] Federal Trade Commission. ‘Federal Trade Commission and Justice Department Seek to Strengthen Enforcement Against Illegal Mergers’, 18 January 2022.

[15] Sigit Haryadi, ‘Telecommunication Quality of Service Concept’, in Network Performance and Quality of Service Lecture, 2016.

[16] Kalyan Parbat, ‘Telecom Companies Reject Trai Plan to Compute Call Drop Rates’, The Economic Times, 14 November 2016.

[17] https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/attachments/us-submissions-oecd-2010-present-other-international-competition-fora/non-price_effects_united_states.pdf

[18] Carl Shapiro, ‘Competition Policy in the Information Economy’ (University of Berkeley, August 1999).

[19] Carl Shapiro, ‘Competition Policy in the Information Economy’.

[20] https://dpiit.gov.in/sites/default/files/DraftNational_e-commerce_Policy_23February2019.pdf Pg. 13

[21] Cheng, Shin-Ru. ‘Entry Barriers: The Role Of Big Data In The Online Networking Market’. SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY, 23 December 2021.

[22] Cheng, Shin-Ru. ‘Entry Barriers: The Role Of Big Data In The Online Networking Market’.

[23] Carl Shapiro, ‘Competition Policy in the Information Economy’.

[24] Carl Shapiro, ‘Competition Policy in the Information Economy’.

[25] ‘Facebook, Inc., v. FTC ’, 9 December 2020.

[26] ‘TikTok Overtakes Facebook as World’s Most Downloaded App’, Nikkei Asia, accessed 17 October 2022.

[27] Yoni Heisler, ‘Facebook’s Plan to Copy TikTok and Change the Feed Is a Horrible Idea’, BGR, 19 June 2022.

[28] Ishaan Gera, ‘Two Years on, Not One Indian App within Reach of TikTok’s Popularity’, 31 May 2022.

[29] OECD, Enhancing Access to and Sharing of Data: Reconciling Risks and Benefits for Data Re-Use across Societies (OECD, 2019), doi:10.1787/276aaca8-en.

[30] ‘WTO | Legal Texts – Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights as Amended by the 2005 Protocol Amending the TRIPS Agreement’. Accessed 17 October 2022.

[31] WTO | Legal Texts – Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights as Amended by the 2005 Protocol Amending the TRIPS Agreement’.

[32] Shamnad Basheer, ‘Database Protection in India’, SpicyIP, accessed 17 October 2022.

[33] Shamnad Basheer, ‘Database Protection in India’.

[34] Shamnad Basheer, ‘Database Protection in India’.

[35] ‘UK-India Free Trade Agreement: The UK’s Strategic Approach’ (Department for International Trade, 13 October 2022).

[36] Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Contestable and Fair Markets in the Digital Sector (Digital Markets Act)’. European Commission.

[37] Summarised from Nikolas Guggenberger, ‘Essential Platforms’, Stanford Technology Law Review 24, no. 2 (2021): 237–343.

[38] Abbott B. Lipsky, ‘Essential Facilities Doctrine: Access Regulation Disguised as Antitrust Enforcement’, SSRN Scholarly Paper (Rochester, NY, 11 November 2020), doi:10.2139/ssrn.3733729.

[39] Abbott B. Lipsky, ‘Essential Facilities Doctrine: Access Regulation Disguised as Antitrust Enforcement’.

[40] Abbott B. Lipsky, ‘Essential Facilities Doctrine: Access Regulation Disguised as Antitrust Enforcement’.

[41] Struble, Tom. ‘For Internet Gatekeepers, Consumer Protection Laws Are Better than Utility-Style Regulation’. Brookings, 26 September 2017.

[42] Struble, Tom. ‘For Internet Gatekeepers, Consumer Protection Laws Are Better than Utility-Style Regulation’.

[43] Struble, Tom. ‘For Internet Gatekeepers, Consumer Protection Laws Are Better than Utility-Style Regulation’.

[44] ‘Recommendations on Regulatory Framework for Over-The-Top (OTT) Communication Services’ (Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, n.d.).

[45] Recommendations on Regulatory Framework for Over-The-Top (OTT) Communication Services’.

[46] Summarised from Srinivas, Kirthi. ‘CCI Issues Interim Order to Relist FabHotels and Treebo’. Competition Law, 5 April 2021.

[47] Competition Commission Of India vs Steel Authority Of India & Anr (Supreme Court of India 9 September 2010).

[48] Konstantinos Efstathiou, ‘The Alstom-Siemens Merger and the Need for European Champions’, Bruegel, 3 November 2019.

[49] Konstantinos Efstathiou, ‘The Alstom-Siemens Merger and the Need for European Champions’, Bruegel, 3 November 2019.

[50] Elie Cohen, ‘Alstom-Siemens, Politique de La Concurrence Ou Politique Des Champions Européens’, Telos, 5 February 2019.

[51] Elie Cohen, ‘Alstom-Siemens, Politique de La Concurrence Ou Politique Des Champions Européens’, Telos, 5 February 2019.

[52] Elie Cohen, ‘Alstom-Siemens, Politique de La Concurrence Ou Politique Des Champions Européens’.

[53] ‘A Franco-German Manifesto for a European Industrial Policy Fit for the 21st Century’ (The Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, Germany and Ministry of Finance, Economy and Industrial and Digital Sovereignty, France, 3 November 2019).

[54] Elie Cohen, ‘Alstom-Siemens, Politique de La Concurrence Ou Politique Des Champions Européens’.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV