China is a 'wall-building country': It built the Great Wall to keep enemies away. In recent times, it built its 'firewall' to ban world-conquering companies like Google, Facebook and Twitter. There are numerous such ‘walls’ — real and virtual — all over China, but you rarely get to see them. Hence, if you really want to understand China, you will have to look at what lies behind them — and even then, you are never sure if what you see is real or virtual. This is an account of the visit made to this mysterious, perplexing land which has, in recent decades, attracted global attention as never before.

Shapeless, densely packed buildings, narrow roads with cars parked alongside — the image, in parts of the rapidly transforming urban landscape, is akin to Mumbai. This is the city of Dongguan in China. The Dongguan Planning Exhibition Gallery displays a picture of the city as it looked a few decades ago:

Today’s Dongguan is an astonishing comparison of contrasts. A glittering metropolis situated on the banks of the Pearl River, with well-planned and well-paved roads, flyovers, skyscrapers, lavish shops, and the fast-paced, five-star lifestyle of its people. The magical transformation of Dongguan has taken place just in the past 30-40 years. The city has become the factory of the world. It has attracted huge foreign investments. With an annual growth rate of 18 percent, Dongguan, a middle-sized village, has become a vibrant metropolis.

The dramatic transformation of Dongguan was portrayed before us in the sprawling and futuristic town planning exhibition centre. Images were projected on a 180-degree screen that occupied the entire space in front and around us and even under our feet. We stood on something like a first-floor balcony as the story of the creation of Dongguan city was being played out. The narration was in Mandarin with English subtitles, accompanied by Chinese music. As the five-minute film came to an end, the screen below split into two. What emerged was an impressive 3D model of tomorrow's Dongguan, a 21st century smart city. Everything was lavish yet minutely detailed, and meticulously presented. "The manufacturing hub which was Dongguan of yesterday, is going to be converted into an eco-friendly and smart metropolis," read the subtitles. All we could say was, "Wow!"

Behind the wall

Every town in China shares this 'American Dream' of development and Dongguan is no exception. Of course, nobody said anything about the other side of the glitter. Our enquiries revealed that Dongguan used to be known as China's 'sin city' or 'sex capital'. Prostitution is banned in China, but it thrived here. The city is still known to attract investors from all over the world to enjoy ‘Dongguan-style hospitality'. Tourists, too, abound on account the city’s proximity to Hong Kong.

There was a big scandal in 2014 when CCTV, the government-owned television news reported the sex racket, drawing swift and severe action. Nearly 2,000 underground joints were raided in a matter of days. Thousands were arrested and the police chief of Dongguan city had to quit. Despite the crackdown, the shady business covertly continues till today. One can get numerous references by merely Google-searching ‘Dongguan’. Nobody mentioned this side of Dongguan to us there; it was all so goody-goody. But we could gradually discern the wall between the real and the virtual in China.

Then came the questions: Why is Google banned in China? What are free media and controlled media? On returning to our hotel, the TV showed one CCTV channel after another. CCTV is a network of as many as 50 channels. All the media in China are either government-owned or under its firm control. Be it Xinhua, the state-owned news agency or the People’s Daily, the newspaper group; they all are official mouthpieces of the Communist Party of China. The local media prints only what the government tells them to. Although we knew this before, the first-hand experience reinforced the importance of the independent media in India.

It’s not just media, whatever happens in China is controlled. Every public activity is watched closely. The Chinese government ensures that no incident ever slips out of its grip. Many streets in China are lined with rows of trees, their trunks supported from all sides by bamboos. It appears as though even the trees must grow as commanded by the government. This scene was symbolic of the extent of the iron grip of the ruling power and it is evident everywhere.

The need to see behind the wall

One nation and one ruling party. The Communist Party of China has ruled the nation since 1 October 1949. China has established a strong system to maintain the monolithic rule, which has, since the 1970s, pursued a unique and determined model of development. You may accept it or you may not, but China has made resolute efforts to prove its merit to the world. Prima facie, the result is stunning. One may wonder if the such a model of development is sustainable; or why there is no transparency or if it has a human face; but it is absolutely undeniable that what has been achieved so far is the result of a novel experiment in the history of human civilisation. And therefore, it is critical for the world, and India, in particular – where we still grapple with human development issues faced by China in the not-too-distant past – to understand it.

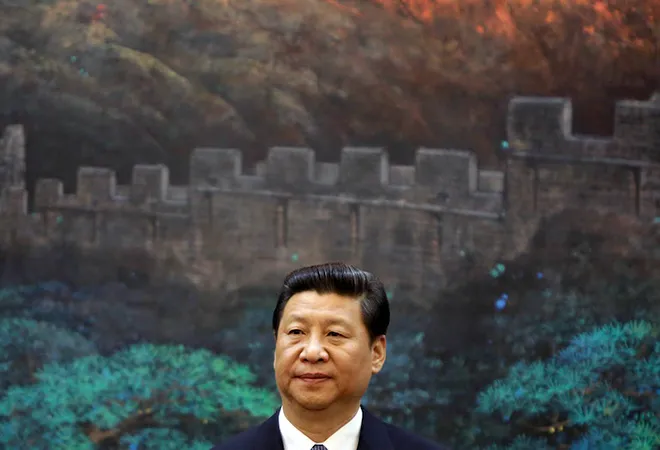

Tomes have been written on how Chairman Mao executed his idea of the Cultural Revolution and how his successor Deng Xiaoping brought in what is today referred to as the Chinese-style capitalism. And how, under President Xi, China is all set to embrace ‘Socialism with Chinese Characteristics’ for what it calls its ‘New Era’. The system has been lauded as much as being criticised for its brutality. It is not possible to understand China unless both these views are understood.

From India’s perspective, one has to explore all the multiple views in order to study China — but begin by distancing oneself from the ‘Hindi-Chini Bhai-Bhai’ refrain of the 1950s as well as the sentiment of betrayal after the 1962 war. Despite the blow-hot, blow-cold relationship between our two countries, the fact remains that India shares its substantial boundary with China – and everything that happens there will continue to affect us. An unbiased and nuanced study of the Chinese development model is critical for India as both the good and the bad effects of the experiment are emerging now.

Having said that, the study of Indo-Sino relations is also equally important, not only in the context of geopolitical and geo-economic perspectives, but also in respect of trade, political systems, urbanisation, culture and language. India and China together account for 40 percent of the global population and how their bilateral relationship pans out is significant not only for the two countries, but human civilisation itself.

A number of Chinese universities have equipped themselves to conduct such studies in great detail. We saw the Indian tricolour fluttering along with the Chinese flag at the entrance of Guangdong University in Guangzhou, where we had an interaction with senior faculty. Large electronic sign boards on all the buildings in the campus scrolled messages welcoming us in both Mandarin and English. The speeches and presentations of the Chinese delegates during our interaction made it amply clear that they were observing all socio-economic and socio-political developments in India with a keen eye. Their educational and research institutions are studying India in an organised way.

We had the opportunity to visit many such institutions and universities in four different cities in China and this was evident everywhere. The discussions we had with their academics ranged from their understanding of India, Sino-Indian border dispute, the ambitious Belt and Road Initiative, their position regarding CPEC and Pakistan, Dalai Lama and India, impact of US on the world in the Trump era, and so on. The thoroughness of their study on the developments in India and the world was impressive. Series of interactions with students, scholars, academics and diplomats in China exposed us to the extent and depth of their study of India and of global affairs, painfully reminding us that India has a lot of catching up to do.

Though India is studied in depth across China’s universities, it is not conspicuous in public life. The general perception of India among average Chinese is of the former being just another nation, not very prominent on the global stage.

The five-storeyed Beijing Foreign Language Book Store on Wangfujing Street, a popular tourist spot in Beijing, has a colossal collection of books from all over the world — but not a single book from India. The rows upon rows of shelves displaying global tourism books too had nothing on India. A whole floor was devoted to books in foreign languages such as English, Japanese and Korean; again, nothing from India. While this gave some idea of the general absence of India from the Chinese conscience, it also made us wonder if at all India is making any determined efforts to project our languages and culture on the global arena.

Dealings between two countries generally take place on three levels – G2G (Government to Government), B2B (business to business) and P2P (people to people). Indo-Sino relations seem to be taking place only on the first two levels, and that too in a prejudiced manner. The two countries cannot hope to have stable and peaceful relations unless the people of both countries develop cordial relations based on mutual trust. This is precisely what needs to be done on both sides of the border.

We had meetings with Vijay Gokhale, then ambassador of India to China and KV Kamat, the chairman of the BRICS’ New Development Bank, in which they highlighted an important aspect of the Chinese people: They said that the Chinese are a very hard working people. You can find a Chinese sweeper diligently sweeping a road shivering in the cold at dawn, even if nobody is watching him. Everyone, right from a sweeper to a CEO, will be found toiling hard to prove himself. They are also confident of the fact that China has now firmly “arrived” on the world scene. The China of today is a product of the ambition which has emerged out of this confident, disciplined and hardworking nature of its people.

Many have described what China had to endure during the transition from the Cultural Revolution to the practice of capitalism. Capitalism always comes with its own baggage of values. Various consequences of capitalism, such as rising income disparity, excessive hedonism, wastage of natural resources, deteriorating environment and the consequent pollution, health problems, widening gap between the urban and the rural life are surfacing as serious threats in China today. It is claimed that the government is taking action in this regard, but no factual details are available.

China’s development — cosmetic or real?

We were driving along a street with elegant buildings on both sides when we came across an old locality which was being demolished. Our persistent inquiries revealed that the old structures were going to be replaced by new buildings. Such “redevelopment” is close to the heart of a person from Mumbai and we were curious to know more. Persistent questions revealed that once redevelopment is planned, the old residents are given a date by which they have to vacate their houses. A young Chinese officer explained: “Generally, a majority of them agree, as the compensation offered is more or less based on the prevailing real estate rates. The 15-20 percent who do not accept the compensation, are engaged through discussions with the local municipal officers and it is not too difficult to crack them. But if anyone – and that is hardly the case – remains adamant, he/she is dealt with in our own Chinese way”. The equations behind the agility of the Chinese development model became clear.

The Tiananmen Square incident made it vividly clear as to what happens when there is opposition to the government; and as a result, fear of the law has taken firm root in the social mindset. In 1989, thousands of citizens, mostly students, had gathered in the Tiananmen Square in Beijing to agitate against the Chinese government. The agitation in the Tiananmen Square, which provides the entrance to the historic Forbidden City, the sprawling ancient royal palace, went on for about one-and-a-half months. The Government tried talking to the agitators, but to no avail. On 4 June 1989, the Red Army tanks crushed the agitators and till date nobody knows the exact number of casualties. No one knows what happened to the particular agitator who became the global face of the struggle, with newspapers across the world carrying his picture standing on a tank in a show of daring defiance.

The government persists in calling the events of 1989 merely as ‘an incident’ of no consequence; however, the terror sowed in the minds of the Chinese by its government still persists. The increasing disparity and below-the-surface resentment among the Chinese is considered by many Western scholars as a trigger for such mass anti-government protests in the future. However, the new model of development adopted by the Chinese government and the material gains it has brought to its people – at least in the country’s numerous futuristic cities and town, state otherwise.

We took a Chinese guide to a mall in Guangzhou to buy protective gear against the colder regions on our itinerary. She said: “There was no mall nor were so many people around; I owe my job to all this development. I can’t even imagine where I would be without this development.” If the opinion of that 30-year-old girl is to be taken as representative; then surely the youth is happy with the development. If not Google, they have Baidu through which they are connected to the Internet. As we persisted with our questions, she admitted that the current model of development is not entirely satisfactory, but is was indeed necessary. “I have yet to make a lot of money and realise my dreams,” she added.

Innumerable such dreams are racing on the streets in China. They have their Audis, Mercedes, Jaguars, Porsches and Teslas and one sees them attired in Western clothes, moving about on the Shanghai bund or Wangfujing street in Beijing, wielding ultramodern gadgets. Or shaking a leg in pubs and bars. Immersed in their own thing, they are oblivious to the disapproval of the older generation. Everywhere, one sees the evidence that the sails of the Chinese ship are full blown with the winds of material pursuits.

Today, this new development model has pervaded all of China but it is also being discounted as a perverted copy of the US. Questions are being asked in private as to who the beneficiaries of the development are and if it is affordable and sustainable, but nobody is willing to go public. However, the crucial question is: how long can the Chinese government keep the aspirations for freedom at bay? There was no social media, no internet when Tiananmen Square happened; will the government be able to similarly suppress a protest today and also get away with it?

The Chinese reality today comprises large-scale urbanisation, modern infrastructure, employment generation through new industry, new education, technological progress and the resultant purchasing power in the hands of the people. People seem to have acknowledged this model as their own. Everyone aspires to be rich, to buy a car, to own a house. This infatuation with personal prosperity is taking China away from its Communist values, towards individualism bred on a Western model of development. We can always ponder over its future course; but we will have to be patient to see how it turns out eventually. Some feel the future is going to be rosy, while there are others who fear the bubble is going to burst. Whatever the outcome, it will have serious global ramifications.

Use of plastic surgery to improve the way one looks is the ‘in thing’ in today’s China. Billions of Yuans are being spent on changing the shape of the nose, the slant of the eyes, the flow of the hair and the cosmetology market is flourishing by the day. There are cosmetic parlours everywhere and the media is full of stories on the subject; leading one to infer that like the Chinese citizen, the Chinese economy too is intent on changing its looks. Let us leave it to time to decide if the face of the development is real or one altered by plastic surgery.

Language is glue that binds China

The Mandarin language is the glue that binds China. It is the only language spoken by most. Wherever you go, you will find deals being made in Mandarin. No shop has its names and signboards in English only. Many a time it is impossible to have even an official conversation without an interpreter, but the Chinese do not perceive it as an impediment. It is what holds the whole of China together.

We perceive the language barrier, not they – because they have learnt the art of communicating with a foreigner customer. As a first step, they have converted all their numerals into Roman form. Visit any shop and point a finger at an object you wish to buy; the shopkeeper will write its price on his calculator. The whole bargain process is, from that point on, is done on the calculator as you erase his quoted price, and write a lower one. All this is done with just a smile, without even one word spoken. Language does not become an obstacle in trade. A variety of notable country heads to industry tycoons, have spoken publicly in Mandarin, with varying degrees of success, to impress the Chinese regime. This highlights that Mandarin language was never a hindrance for China to integrate with the globalised world.

Upside down world view

During our stay in Hangzhou, we visited Alibaba, the extremely popular e-commerce giant, which has now diversified into a multidisciplinary service provider of Internet of Things. Its founder Jack Ma, the richest Asian, is China’s hero today, while Alibaba, one of the world’s biggest IT companies.

Alibaba reflects this Chinese tendency to view the world through their own eyes. The Chinese dictum is to study the world, not copy it; take whatever suits the circumstances and create a new system. It makes one remember the schoolbook account of Huan Tsang, the Chinese traveller who had come to India a few thousand years ago. He too had visited Nalanda University and other places, gathered whatever knowledge he could from there and returned to China to rearrange and spread the knowledge anew.

Today, everyone in China knows of Alibaba and uses the Ali-pay mobile wallet. China has already achieved the dream of cashless economy through the medium of Alipay while we are still dreaming. A peculiar principle of Jack Ma is framed in Alibaba’s headquarters in Hangzhou. It shows his staff upside down and carries the legend: “To see the world in another point of view!”

Like them, can we turn ourselves upside down?

This commentary originally appeared in First Post.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV