Three of the fastest-growing applications of artificial intelligence (AI) today are a manifestation of patriarchal stereotypes — the booming sexbots industry, the proliferation of autonomous weapon systems, and the increasing popularity of mostly female-voiced virtual assistants and carers. The machines of tomorrow are likely to be either misogynistic, violent or servile.

Sophia, the first robot to be granted citizenship, has called for

women’s rights in Saudi Arabia and

declared her desire to have a child all in the of one month. Other robots are mere receptacles for abuse.

The Guardian in 2017

reported that the sex tech industry, including smart sex toys and virtual-reality porn, is estimated to be worth a whopping $30 billion. This is just the beginning. The industry is well on its way to launch female sex robots with custom-made genitals and even heating systems, all in the quest to create a satisfying sexual experience.

The advent of sexually obedient machines — which are designed to never say no — is problematic not just because of the presumption that women can be replaced, but because the creators and users largely tend to be heterosexual men. The

news of a sex robot being molested, broken and soiled at an electronics festival in Austria last year should hardly come as a surprise.

The advent of sexually obedient machines — which are designed to never say no — is problematic not just because of the presumption that women can be replaced, but because the creators and users largely tend to be heterosexual men.

While one could argue that the use of sexbots could reduce the abuse and rape of women in real life, it is undeniable that these machines are created to serve some men’s perverse needs. The machine represents a new wave of objectification, one that could potentially exacerbate violence against actual women.

The arrival of lethal autonomous weapon systems (LAWS) or “killer robots”, on the other hand, threatens to de-humanise both the male and female victims of war.

On the one hand, autonomous weapons could reduce the number of humans involved in combat and even decrease casualties. Killer robots could ultimately bring down the human cost of wars. On the other hand, they could downplay the human consequences of combat — and indeed, violence itself — and lower the threshold for armed conflict.

Several states are calling for a pre-emptive ban of killer robots, afraid that they might lead to an AI arms race, one that could raise the risk of a violent clash. Should machines be allowed to make life and death decisions? Or should this choice stay in the hands of humans, however fallible they may be?

On the one hand, autonomous weapons could reduce the number of humans involved in combat and even decrease casualties. Killer robots could ultimately bring down the human cost of wars.

Finally, the development of voice assistants and Internet of Things (IoT) devices for the care of children and senior citizens is a market that is expected to expand rapidly in the next decade. The presumption that machines cannot invoke the emotional intelligence that care workers possess is increasingly being challenged with the emergence of smart tracking devices and health monitors that can observe and predict behaviour.

These innovations no doubt share their underlying technology with other voice-driven platforms such as virtual assistants — platforms often designed to mimic servility and subservience. It is no coincidence that voice assistants are often designed to sound and act feminine — take Apple’s Siri (in its original avatar) and Amazon’s Alexa. The more recent development of a ‘male’ option for voice assistants does not change the overall picture of male dominance and female servitude in AI.

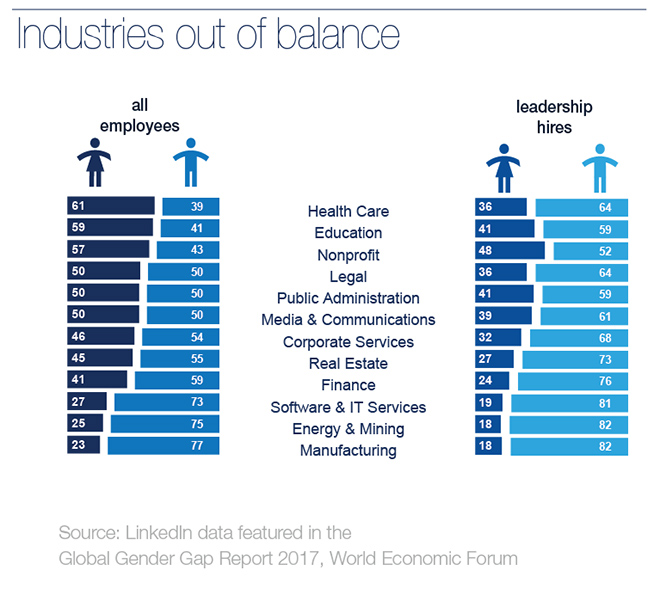

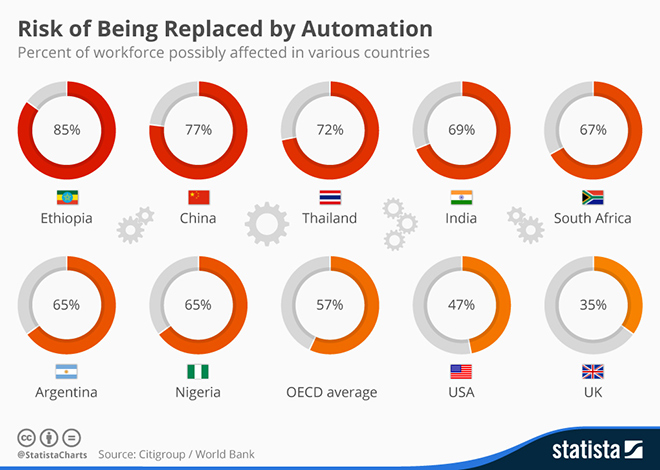

Robots are expected to replace workers around the world.

When chatbots and voice assistants are fed on a diet of data assembled by male coders, machines perpetuate inequities found in the real world. This can have unintended consequences.

Given the general uncertainty surrounding the impact of AI on the real world, the responsibility of creators as well as broader communities merits all the more attention.

Today, machines reflect regressive, patriarchal ideas that have proven to be harmful to society. If this continues, technology may no longer usher us into a post-gender world. In fact, like all bad doctrines that have held communities back, biased codes may just institutionalise damaging behaviour.

Given the general uncertainty surrounding the impact of AI on the real world, the responsibility of creators as well as broader communities merits all the more attention.

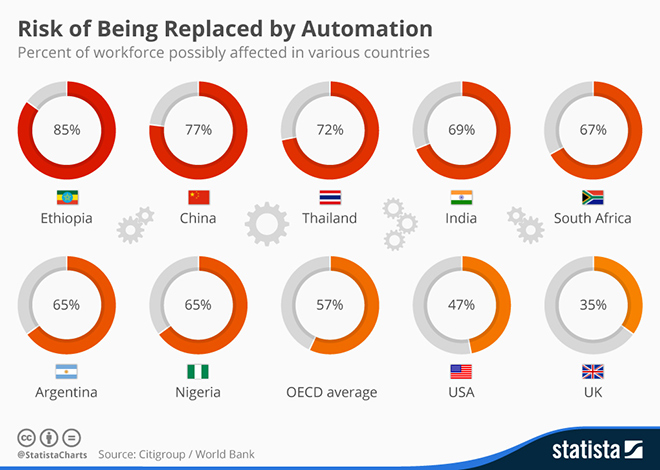

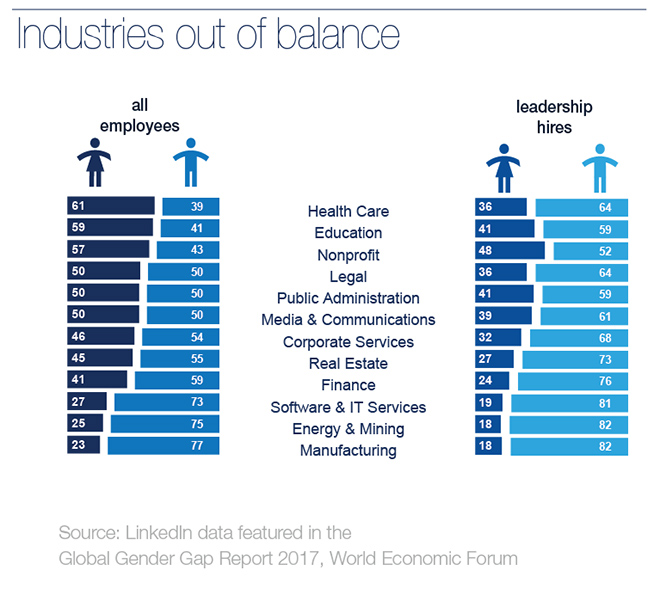

Perhaps the involvement of more women and marginalised communities in the creation of AI agents could deliver the equity that we desire in future machines, and prevent the development of more patriarchal technology. If the machine is patriarchal, do we remove the more systemic condition of patriarchy or reduce reliance on the machine altogether? Both are easier said than done.

To build an equitable world, which will be inhabited by women, men and machines, the global community needs to script norms around the fundamental purpose, principles of design and ethics of deployment of AI, today.

Autonomous systems cannot be driven by technological determinism that plagues Silicon Valley — instead their design should be shaped by multiethnic, multicultural and multi-gendered ethos. AI and its evolution, more importantly, needs to serve much larger constituencies with access to benefits being universally available.

The administration of AI applications cannot be left to the market alone. Experience tells us that the market often fails and is regularly compromised by perversion and greed. History teaches us that when governments control, constrain and constrict innovation, they produce aberrant outcomes that are far from ideal. Norms developed by communities, instead, provide a workaround. We must promote norms that manage these technologies, make it available to those who need it most, and ensure a gendered development of this space led by a multistakeholder community that includes voices from outside the Atlantic consensus.

This commentary originally appeared in World Economic Forum.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Robots are expected to replace workers around the world.

Robots are expected to replace workers around the world.

PREV

PREV