Introduction

The Indian government estimates that the country needs to spend 7-8 percent of its GDP on green infrastructure each year, an annual investment of US$200 billion up to 2030. The International Finance Corporation (IFC) estimates for climate-smart investment are even higher, at US$3.1 trillion up to 2030, which implies an annual investment of US$300 billion.

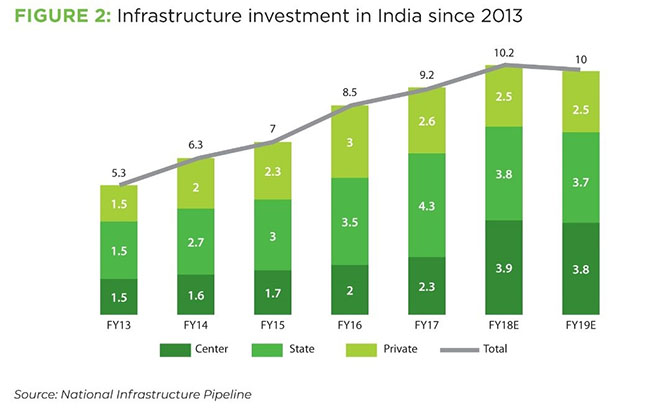

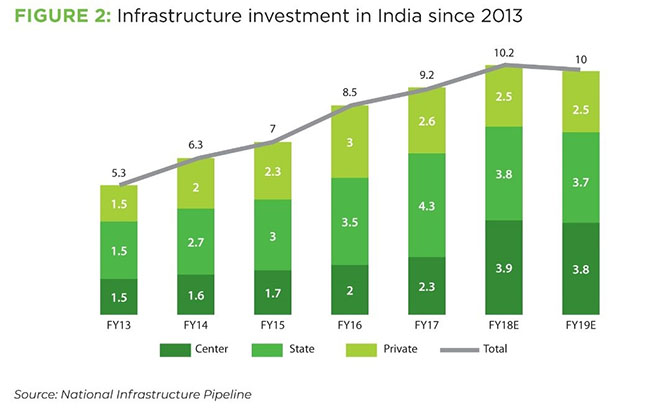

Currently, infrastructure investments in India average around US$100-110 billion annually, far below what is required. While the government has released a US$1.4-trillion infrastructure pipeline for the next five years, there is no specific focus on green infrastructure other than renewable energy. The pipeline depends on significant participation from the private sector. It is expected to contribute around 22 percent of the projects (with the state and central governments contributing 39 percent each), and to finance the entire investment in renewable energy (around US$120 billion) over the next five years.

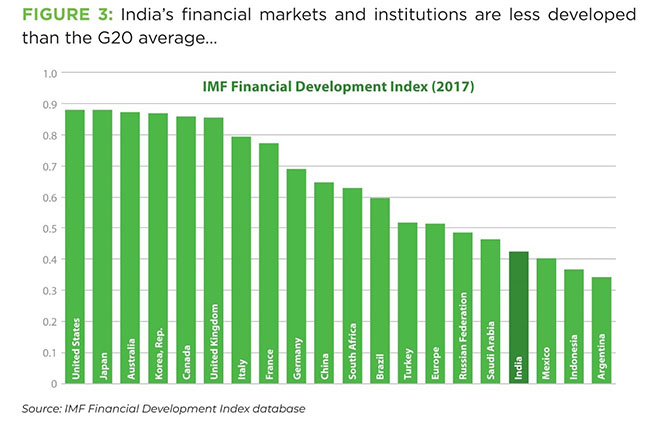

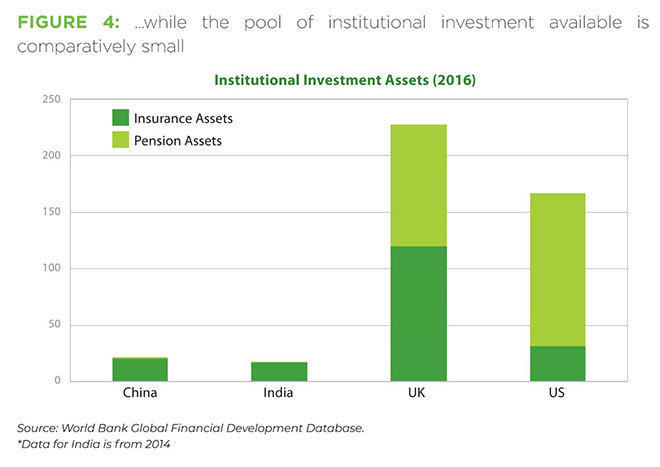

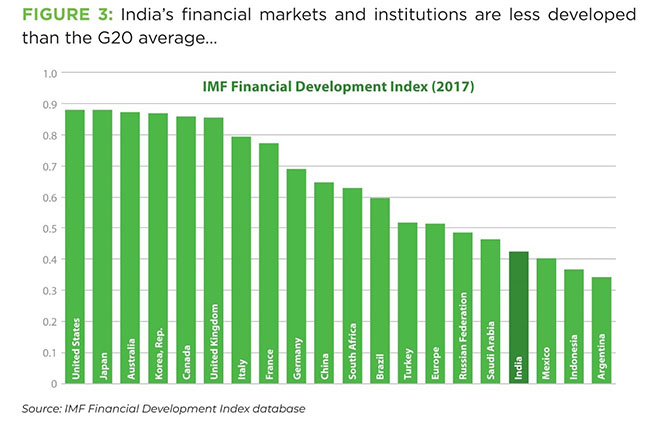

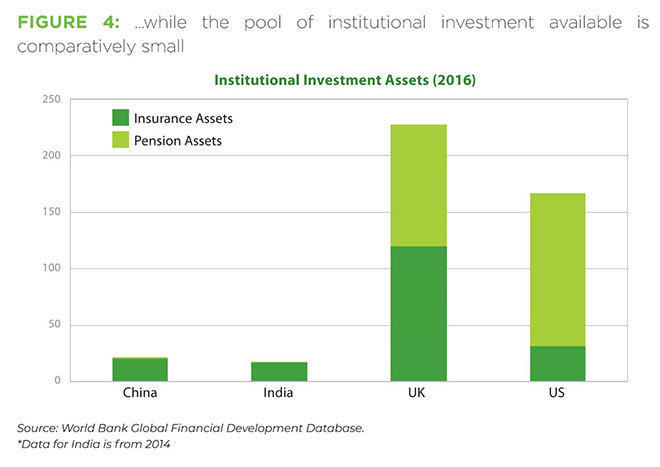

To build the infrastructure India needs over the next decade and ensure that it is environmentally sustainable and climate change resilient, the private sector’s contribution will need to increase and include foreign capital. Domestic financial markets and institutions, which have so far been important sources of finance, are currently in crisis, with the bank and non-bank financial sector holding a large proportion of non-performing assets and low levels of liquidity. Also, infrastructure projects that have long gestation periods, uncertain yields in the first few years of investment, and unclear exit strategies are inherently challenging to finance for deposit-taking institutions. In India, however, the financial markets are relatively undeveloped compared to the G20 economies, and the domestic pool of institutional investment is small (see Figures 2 and 3).

While the foreign capital pool is large and well-suited to financing infrastructure investment, accessing this finance is complicated. The World Bank found that in the 2011-17 period, institutional investors had not financed a single infrastructure project in South Asia, primarily because investing in emerging market infrastructure is perceived as high risk. Research from the Asian Development Bank shows that the share of infrastructure bonds rated AA and above is about 52 percent in Europe but only about 16 percent in Asia. This raises the cost of finance, particularly for pension and insurance funds, which have high capital adequacy requirements, against such investments. Other challenges to institutional investors in emerging-market infrastructure include the lack of a pipeline of bankable projects, foreign exchange risks, perceived political risks, uncertain yields and a lack of information about the sector.

Project risk needs to be mitigated to facilitate the entry of foreign institutional investors into India’s infrastructure sector. Public funds can play a catalytic role in achieving this by making the initial investment, absorbing most of the risk and accepting lower rates of return. Once the project shows signs of profitability, commercial investors can enter and get higher rates of return.

As countries move to mitigate the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, there may soon be an increase in cross-border capital flows. Currently, the major economies are facing a sharp slowdown in growth, massive unemployment and the largest financial market crash in decades. While the current focus is on improving healthcare, providing a social safety net, and developing medication, tests and a vaccine, a global stimulus will be launched over the next few months to mitigate the economic impacts. The G20 has already announced a combined US$5 trillion fiscal expansion. Major central banks, including the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank, have started large-scale asset purchase programmes designed to flood financial markets with liquidity.

As developed economy interest rates approach the zero-lower bound, experience suggests this money will soon be searching for yield, including in the emerging markets. While India saw large inflows of foreign capital after the 2008 global financial crisis, these investments were predominantly confined to debt and equity markets and reversed rapidly when global economic conditions turned volatile. India must find an avenue to direct this funding toward long-term infrastructure investment.

The pandemic is also changing the way financial risks are measured. March 2020 had the fastest pace of rating downgrades since 2002, with more expected in the weeks ahead. As risk profiles are re-assessed, exogenous events are likely to be given larger weights. This could lead to climate risks being considered more seriously in financial portfolios. Financial regulators across the world have stated that climate-related risks are under-priced and have been pointing to recent extreme climate events as a wake-up call. Despite this, the shift to green finance has not reached the pace required to avoid catastrophic climate change. The Covid-19 crisis could bring such systemic risks front and centre, providing the impetus needed to re-evaluate financial models and, consequently, greater support for green investment.

In anticipation of the greater focus on green investment and the global financial markets being flush with funds, India must create an institutional structure to attract this capital to its infrastructure sector. India has already had some success with renewable energy. In the public sector, the Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI) has used direct investment in land acquisition and a payment security mechanism to encourage private power developers to set up solar parks. The Indian and UK governments have jointly set up the Green Growth Equity Fund (GGEF) to encourage the UK financial sector to invest in India. Tata CleanTech Capital Limited (TCCL), India’s first ‘green bank’, is a private non-bank financial company set up with support from the IFC, and has mobilised US$700 million from an initial investment of US$130million.

To fulfil the need for investment in infrastructure sectors other than energy, such institutions must expand, find new financial instruments and create a pipeline of viable projects. As the mandate for environmental, social and governance investment has expanded worldwide, there is likely to be a large pool of finance available, provided there is an institutional and regulatory structure to make these projects attractive to investors. Technical capacity building will also be required to ensure that investments are structured to fit green norms.

This report proposes the establishment of an Indian ‘green investment bank’ that will use public funds to generate private finance for green infrastructure investment, considering the quantum of finance needed and the specific needs of an economy transitioning to environmental sustainability while maintaining high growth rates. This requires projects to be economically viable to compete with incumbent technologies and be scaled up across the country. Additionally, the areas covered, such as energy and transport systems, will require the creation of new markets and the participation of several stakeholders. To get many actors to buy in, these will have to be profitable.

While the government’s ability to provide a stable stream of seed capital and mitigate credit risk could help in the initial years, the initial funding could also be provided/supplemented by multilateral institutions and philanthropists. Strict limits should be imposed on the government’s level of control over day-to-day activities and choice of investment to ensure that decisions are taken in line with the institution’s mandate and are free from political interference. The bank and government should, however, coordinate on regulatory and fiscal policies. For the bank to succeed in shifting the economy to a low-carbon path, finance will need to be complemented with other policies, such as carbon emissions standards or new technology subsidies.

Find the full report here

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV