Introduction

In recent years, the subject of maritime ‘grey-zone operations’ has drawn increased debate and discussion. The ‘grey-zone’ is a metaphorical state of being between war and peace, where an aggressor aims to reap either political or territorial gains associated with overt military aggression without crossing the threshold of open warfare with a powerful adversary.[1] The ‘zone’ essentially represents an operating environment in which aggressors use ambiguity, and leverage non-attribution to achieve strategic objectives while limiting counter-actions by other nation states.

For some time now, the organisation and approach of insurgent groups in the terrestrial domain has been one of asymmetric attrition, whereby low-intensity and sporadic attacks have been launched against security forces. The strategic logic behind this tactic is that it is hard for the constituted government or occupying power to sustain the financial and political cost of high-security presence for any long period of time.[2] In a maritime context, however, these low-grade attacks have often been carried out by non-state actors and agencies in concert with military or coast guards in a way where the latter’s involvement has been less than conspicuous.

The leading purveyors of grey-zone tactics in maritime-Asia are China’s irregular maritime militias, dubbed ‘little blue men’ that seek to assert and expand Chinese control over an increasingly large area of disputed and reclaimed islands and reefs in the strategically important South China Sea.[3] These sea-borne militias, comprising hundreds of fisherfolk in motor-boats, as well as China’s paramilitary forces, are based mainly on China’s Hainan Island and have been involved in “buzzing” US navy ships and those of neighbouring countries with rival territorial claims.

The idea behind Chinese militia operations is to exert authority over a maritime space using civilian craft and personnel, but doing it in a way that precludes open military confrontation. By acting assertively and unprofessionally in the vicinity of other states, China’s Coast Guard boats and fishing vessels seek to assert dominance in areas surrounding disputed features. Their activities are consciously kept below the threshold of conflict, yet demonstrate China’s resolve to establish control over disputed features.

After Chinese maritime militias assisted in the seizure of the Scarborough Shoal in 2012, Beijing expanded its ‘hybrid’ operations in the South China Sea. China also began using its irregular forces to deter US freedom of navigation operations (FONOPS) in the South China Sea.[4] Notably, even as Chinese militias were professionalised, they maintained an ambiguous civilian affiliation, enabling Beijing to plausibly deny grey-zone activity. China has since resorted to illegal reclamation of features in the South China Sea, gradually militarising artificial islands in a bid to establish de-facto control over their surrounding waters. In effect, say maritime observers, China’s structured ‘irregular tactics’ have allowed Beijing to undermine international law and set precedents in its favour.

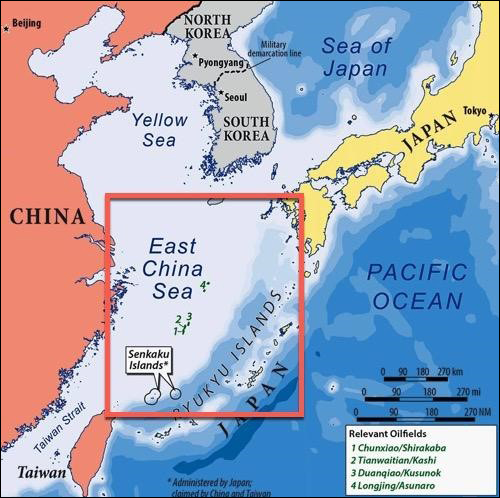

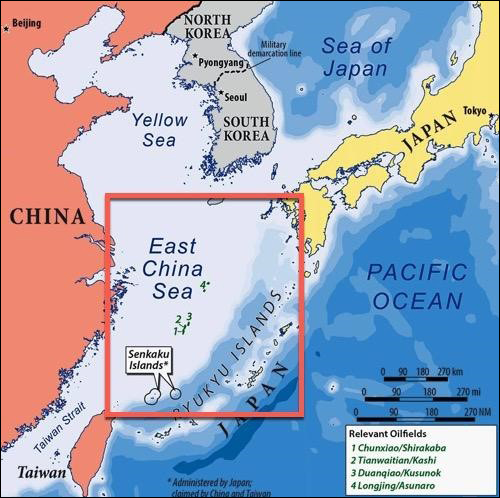

While the focal point of China’s irregular warfare is the South China Sea, the East Sea too has witnessed a significant amount of militia activity. Following Japan’s “nationalisation” of three uninhabited islets in the Senkaku group of islands in September 2012, there has been a marked rise in Chinese government vessel activity in the East Sea.[5] In August 2016, China demonstrated the effectiveness of grey-zone operations by sending over 200 Chinese fishing vessels into the Senkaku seas. In four days, a total of 28 China Coast Guard (CCG) vessels escorting the fishing boats are said to have entered Japan’s territorial seas near the Senkakus.[6] Despite ending peacefully—with no landings on the disputed islands—the operation provided a glimpse of what Beijing’s long-feared, potentially escalatory grey-zone tactics were capable of achieving in a distant Japanese dominated littoral.

Naval analysts also use the term ‘hybrid warfare’ in describing irregular maritime tactics. The origins of ‘hybrid war’ go back to 2005, when James N. Mattis, the present US defense secretary, and National Defense University researcher Frank Hoffman introduced the term into the security discourse, calling it “a combination of novel approaches—a merger of different modes and means of war.”[7]Since then, the use of hybrid warfare techniques has expanded significantly, to include an entire spectrum of threats ranging for Russia and Iran’s blend of military and paramilitary tools, to China’s use of a ‘grey zone’ approach in its near-littorals, as well as the ‘net-wars’ launched by anonymous states and non-state actors.[8]

While ‘hybrid’ and ‘grey-zone’ connote two different conditions, in the context of asymmetric maritime operations, they have frequently been used interchangeably. Retired US Navy Admiral James Stavridis, for instance, argues that “Chinese activities in the South China Sea is hybrid because it represents a ‘non-kinetic’ attempt at influencing strategic competition in maritime-Asia and Europe.”[9] Others have explained ‘grey-zone’ operations as an adversary’s penchant for strategic ambiguity, whereas ‘hybrid’ describes a combination of conventional with irregular instruments of warfare, both in the strategic and political domains.[10] However one defines the two terms, both emphasise asymmetric tactics in the maritime domain.

One of the defining features of asymmetric threats in the maritime domain is that it is often backed by the ability to use other stronger means, as is the case with China. The communist party state, however, is not unique in this respect. In the case of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps Navy (IRGC) too, the asymmetric threat is buttressed by the official power of the Islamic state. The reason Chinese and Iranian militia forces are effective in offsetting stronger opponents is that they are both backed by regular naval forces.[11] Yet, not every irregular force enjoys this advantage. The Sea Tigers of the LTTE movement (The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam), for instance, could not sustain their attacks on the Sri Lankan navy because they lacked the flexibility and tactical agency that comes with the support of a powerful maritime force.

In part, the effectiveness of Chinese maritime militias owes to the active support of the Chinese Coast Guard. With the backing and guidance of CG cadres, China’s irregular forces have assisted in reclamation activities around disputed islands, provided escort services to fishermen in contested waters, and even challenged oil rigs and non-Chinese military presence in the South China Sea. All aspects of militia operations in the South China Sea and East Sea are reportedly controlled by the higher echelons of China’s military leadership.[12]

In Southeast Asia, it is unclear if Vietnam, Indonesia and the Philippines will be able to harness their fishermen to stage asymmetric attacks in the same way as the Chinese militias. Part of the reason is the absence of hard military power to back militia operations. Still, this does not mean asymmetric forces always need active state support. In some cases, like the Iceland-UK Cod wars for fishing rights in the North Atlantic, regular military force was never used.[13] Yet, it is a helpful way to understand how states use symmetric and asymmetric capabilities in tandem to further their national interests.

Coast Guards and Grey-Zone Operations

The most prominent feature of China’s grey-zone tactics in East Asia is its increased use of Coast Guard vessels in coercion operations. In the East China Sea, there has since 2012 been a surge in Chinese Coast Guard presence.[14] China’s vastly capable CG vessels are mostly modified naval warships that are continually deployed in the contiguous zone around the Senkakus, keeping up a regular presence in the territorial sea.[15] Beijing’s regular CCG patrols within the 12 nautical miles zone appear intended at probing a perceived seam in the U.S-Japan security treaty, where US treaty obligations can only be invoked in the event of an armed attack.

In the South China Sea too, China’s growing use of non-conventional means to assert control is raising concerns among neighbouring countries. The Chinese Coast Guard has inducted two massive 12,000-tonne cutters (the Haijing 2901 and Haijing 3901), that have been intimidating and harassing the ships of other states in the South China Sea.[16] With a length of 165 metres (541 feet), a beam of over 20 metres (more than 65 ft), these two cutters are the world’s largest coast-guard vessels and displace more than most modern naval destroyers. As China modifies its naval vessels for maritime law enforcement, many observers suspect that a proxy-naval strategy of hard-power dominance is playing out in maritime-Southeast Asia.

Expectedly, Southeast Asian powers are also beginning to use their Coast Guards to support their own territorial claims. Vietnam recently ordered two 4,000-tonne warships for its Coast Guard, with plans to flood the ‘zone’ with its law enforcement forces during the next standoff with China. The Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia have likewise initiated the buildup of coastal agencies to stave off Chinese aggression.[17]

Regional states are expanding the roles of their coast guards to better come to grips with China’s maritime assertiveness in the contested seas. At a time when the spectrum of maritime-related threats—ranging from natural disasters, piracy and terrorism, to environmental pollution, illegal fishing and migration—is rapidly growing, Southeast Asian states find that they lack the scale and sophistication of capabilities needed to respond to China’s aggressive moves.

Even so, Hanoi’s development of a state-supported fishing boat militia to hold off China at sea has been noteworthy.[18]The injunction to the country’s commercial fishermen to use stronger boats and for military-trained people to prepare for a clash with Chinese militias is being taken seriously by other states in the region, even if some continue to doubt the efficacy of such measures.

The Development of China’s Coast Guard

In 2017, China’s coast guard had 225 ships weighing over five hundred tonnes and capable of operating offshore, and another 1,050-plus confined to closer waters, for a total of over 1,275 ships—more hulls than the coast guards of all its regional neighbours combined.[19] By 2020, the force will have an estimated total of 1,300-plus ships: 260 large vessels capable of operating offshore, many capable of operating worldwide, and another 1,050-plus smaller vessels confined to closer waters. Not only will China add 400 more coast guard ships by 2020, over 200 of these ships will be capable of operating offshore.[20]

More importantly, as China replaces its entire fleet of older and less capable large patrol ships, its coast guard is developing the capability to operate farther offshore for longer periods. China’s new constabulary ships feature helicopter hangars, interceptor boats, deck guns, high-capacity water cannons and improved sea keeping. Most new coast guard vessels, like the new Coast Guard cutter 3901, have the armament of warships—76 millimeter rapid fire guns, two auxiliary guns, and even anti-aircraft machine guns.

The new vessels also have high-output water cannons mounted high on their superstructure. During the HYSY-981 oil rig standoff with Vietnam in 2014, these vessels demonstrated their prowess as they damaged bridge-mounted equipment on Vietnamese vessels and forced water down their exhaust funnels.[21]

A hallmark of China’s Coast Guard modernisation is the development of ships dedicated to particular missions.[22] China’s massive shipbuilding industry is developing vessels that focus on designs oriented toward specific requirements. All these ships and craft remain highly capable of acting in other roles, particularly those related to promoting sovereignty in disputed South and East China Sea areas.[23] In the main, however, China’s new ships play an important role in coordinating elements of China’s maritime militia to ensure a highly organised campaign of harassment and coercion in the contested commons.

Grey-Zone Operations in South Asia

Even as much of the debate around ‘grey-zones’ surrounds Chinese irregular tactics in East Asian waters, there has been some debate over whether South Asia faces a similar threat from non-state actors in the littorals seas. Indeed, beyond violent competition between states in East Asia, the grey-zone also implicates the tension between state and non-state actors in South Asia. How actors in the grey zone break, ignore, and diminish the rules-based international order, upending the established rules of conventional conflict, can best be understood by recounting the recent experiences of the Pakistan navy.

In August 2014, the Al Qaeda staged a brazen attack on Pakistan’s naval dockyard at Karachi, attempting to hijack the PNS Zulfikar, a Pakistani warship.[24]At the time, the ship was preparing to sail for the Indian Ocean to join an international flotilla. The militants, who approached the docked vessel in an inflatable boat wearing marine uniforms, had advance information about the ship’s onboard security arrangements. As they approached the ship, a lone sentry onboard observed the suspicious movements and alerted security personnel. A gunfight ensued in which the attackers were subdued. To Islamabad’s horror, among those that had helped Al Qaeda carry out the attack were radicalised cadres of the Pakistan Navy.[25]

In the aftermath of the attack, Indian analysts considered the prospect of militant activities in India’s near-seas. Could Pakistan-based non-state actors use Pakistani naval assets to launch strikes on Indian naval vessels? Or infiltrate India’s maritime establishments to attack naval assets? The Karachi dockyard attack had been eerily similar to another assault in 2011, when radicalised elements of the Pakistan navy joined forces with Al Qaeda to organise a hit on the PNS Mehran, the PN’s premier naval air-station in Karachi.[26] The attack had followed failed talks between the Pakistan Navy and Al Qaeda over arrested navy personnel with suspected links to the militant organisation. It was clear to Indian watchers that the attacks on Pakistani naval bases were symptomatic of ‘grey-zone’ conditions where the ‘rules of engagement’ (ROEs) had been unclear.[27]

No answers were easily forthcoming, however. Unlike the incremental strategies of Chinese militias in the South China Sea, Pakistani militant forces seemed intent on striking hard. While the absence of communication between rival forces is always a troublesome issue, the Al Qaeda’s approach suggested that the possibility of a negotiated settlement simply did not exist.

There was also the big question that hung heavy in the air: Could the Indian navy sink a Pakistani war vessel being commandeered by Pakistan-based terrorist elements? In the absence of evidence that the militants have been trained, funded or sponsored by Pakistan intelligence or maritime agencies, would the Indian navy be justified in making a preemptive strike on a Pakistani warship? There were many questions, but neither the intelligence nor the law seemed clear about what needed to be done.[28] In the years since, India’s naval planners have been preparing for situations where conventional security measures are rendered ineffective. Not only has the Indian Navy upgraded flotilla security measures in the Arabian Sea, it has also noted the need to deal with hybrid operations in the new maritime strategy document.[29] The Indian Navy’s fears about hybrid attacks in ports and coastal facilities were seemingly validated when intelligence reports in July 2108 suggested that the Jaish-e-Mohammad was planning to attack Indian Navy warships using deep sea divers.[30]

Arguably, the more diabolical demonstration of the grey phenomenon in South Asia came in the form of the 26/11 attack on Mumbai.[31] In November 2008, ten heavily armed Pakistani terrorists, supported by Pakistani intelligence agencies entered India’s premier coastal metropolis via the sea-route, killing 166 people and injuring over 300 in their rampage. The attacks roused the Indian maritime security establishment from its complacency, leading to a significant strengthening of coastal security measures.

It is relevant that violent extremist organisations (VEOs) such as the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) leverage the absence of government authority to carry out irregular warfare. With a permeable environment and minimal government presence, the Indian-Pakistan coast remains open to transient craft.[32] Such an environment offers myriad advantages compared to overland routes where government checkpoints and patrols are far more rigorous. Unfortunately, despite improvements, India’s coastal architecture remains vulnerable from attacks by Pakistan-based VEOs. The lack of governance and increased radicalisation has in fact opened up new ‘grey-spaces’ in South Asia, with non-state actors ever more capable of operating in the vulnerable sub-continental littorals.

China’s ‘Three Warfares’

Away from Pakistan, New Delhi has also had to contend with another form of ‘grey-zone’ tactic that does not involve non-state actors or kinetic attacks. For the past decade, China has been actively deploying the ‘three warfares’ (3Ws) strategy—media, psychological and legal warfare—to weaken Indian resolve in South Asia and the Indian Ocean Region.[33]The 3Ws strategy goes beyond propaganda wars and misinformation campaigns. Expanding conventional war dynamics into the political domain, it is aimed at undermining the adversary’s organisational foundations and military morale. A slow-moving and surreptitious ploy, the 3Ws are designed to subdue the enemy without ever needing to fight.

China’s preferred 3Ws instrument is psychological warfare. The peacetime applications of psy-ops techniques against India involve the use of subtle coercion to influence New Delhi’s decision-making calculus. The Communist party’s media mouthpiece Global Times’ acerbic write-ups regularly seek to shape international opinion, creating doubts, even fomenting anti-India sentiments. China also sends veiled warnings to dissuade India from military activity in territory it claims to be its own. In a maritime context, an overt example of psy-ops was the incident in July 2011 in which a Chinese source is supposed to have issued a warning to an Indian warship, INS Airavat, operating off the coast of Vietnam.[34] China did not own up for the act but it was more than clear to all actors concerned where the warning had emanated from, who it targeted, and what it meant to convey.

Interestingly, China’s ‘three warfares’ seems to be a modern-day version of ‘unrestricted war’, a military concept developed in 1999 by two Chinese colonels, who argued that war had gradually evolved to “using all means, including armed force or non-armed force, military and non-military, and lethal and non-lethal means to compel the enemy to accept one’s interests.”[35] China’s recent installation of marine observatories in the Exclusive Economic Zones of Pakistan and Maldives, for instance, clearly have a dual purpose – marine scientific research and naval surveillance, with the ultimate intention of facilitating forays by Chinese SSN and SSBNs.[36]

Even so, China’s ‘unrestricted warfare’ is seen by many as an explicit response to the US’ overwhelming victory in the 1991 Gulf War.[37] The implication that modern warfare could no longer be limited to military means held true for all of China’s adversaries and competitors. China’s 3Ws is not meant to distinguish between soldiers and civilians; its purpose is to render society into a battlefield. Its only rule is that there are no rules; nothing is forbidden. China’s 3Ws may not be classical asymmetric warfare, but the manner in which it attempts to transcend the traditional concepts of kinetic engagement, gives it an aura of unconventional ‘grey-zone’ tactics. This also means that in order to combat 3Ws effectively, one needs a comprehensive approach encompassing diplomacy, information, the military, and economics.

Conclusion

The future is poised to witness an increase in hybrid warfare in Asia, as aggressive powers seek to blur the lines between military, economic, diplomatic, intelligence and criminal means to achieve political objectives. While full-scale warfare remains improbable, some powerful nations are likely to continue to exploit the ‘grey-zone’ between war and peace to ensure that the balance of forces continues to remain in their favour.

The lessons in the case of Southeast Asia are instructive. China, which helped nurture the grey-zone in the South China Sea, is practically ascendant, with no sign that opponents—including the United States—are willing to take on its subsidiary forces. What works for Beijing is that it has the numbers on its side, with each of China’s three sea-forces possessing more ships than its presumed adversaries. Importantly, the PLAN’s doctrine of operations increasingly recognises this advantage, and the domestic shipbuilding industry too is intent on capitalising on it. Numerical superiority allows China’s forces to flood the maritime grey zone in ways that its neighbours, as well as the United States, may find hard to counter. Understanding this challenge confronting maritime East Asia could be a crucial first step for India in addressing its own issues in the South Asian commons.

For states like India, unaccustomed to maritime grey-zone warfare, the challenge will be to prepare to counter subtle aggression in the littorals, where aggressors will increasingly deploy non-military anti-access measures. The need of the hour for law-abiding states is to continue to work towards a ‘rules-based order’ in the Asian commons. At the same time, regional maritime agencies must be prepared to operate and fight in conditions of increased ambiguity, leveraging all the instruments at their disposal.

Endnotes

[1] Michael Green, Cathleen Hicks, Jack Cooper, “Countering Maritime Coercion in Asia”, Centre for Strategic and International Studies, Jan 2017, https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fspublic/publication/170505_GreenM_ CounteringCoercionAsia_Web.pdf?OnoJXfWb4A5gw_n6G.8azgEd8zRIM4wq.

[2] Micheal John Hopkins, The Rule of Law in Crisis and Conflict Grey Zones: Regulating the Use of Force in a Global Information Environment (Routledge: London and New York), 2017, pp. 38-39.

[3] Andrew S. Erickson and Conor M. Kennedy, “China’s Maritime Militia”, Center for Naval Analyses, February 2016.

[4] China’s militias were used to oppose the USS Lassen’s sail-past the Subi Reef in 2016; See Christopher P. Cavas, “China’s ‘Little Blue Men’ Take Navy’s Place in Disputes”, Defense News, November 2, 2015.

[5] “China’s military is turning its aggressive South China Sea Tactics on Japan”, The Business Insider, January 27, 2018.

[6] Ibid.

[7] J Mattis and F. Hoffman, “Future Warfare: The Rise of Hybrid Wars”, US Proceedings Magazine 2005.

[8] Jack Cooper, Andrew Shearer, “Thinking clearly about China’s layered Indo-Pacific Strategy”, Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, 2017, Vol 73, No.5, pp. 307, http://milnewstbay.pbworks.com/f/Mattis FourBlockWarUSNINov2005.pdf.

[9] Stavridis, J, Maritime Hybrid Warfare Is Coming, Proceedings 142 (12).

[10] Robert Johnson, “Hybrid War and Its Countermeasures: A Critique of the Literature”, Journal of Small Wars and Insurgencies, Volume 29, 2018 – Issue 1, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09592318. 2018.1404770?src=recsys&journalCode=fswi20.

[11] Joshua Himes, “Iran’s Two Navies- A maturing maritime strategy”, Institute for the Study of War, October 2011.

[12]Andrew S. Erickson, “New Pentagon China Report Highlights the Rise of Beijing’s Maritime Militia”, The National Interest, June 7, 2017.

[13] Sverrir, Steinsson, “The Cod Wars: a re-analysis”, Journal of European Security, Volume 25, 2016, Issue 2.

[14] “Four Chinese CG ships enter Japanese waters around Senkakus”, The Japan Times, January 6, 2018.

[15] “Trends in Chinese Government and Other Vessels in the Waters Surrounding the Senkaku Islands, and Japan’s Response”, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, January 4, 2018.

[16] “China Coast Guard’s New ‘Monster’ Ship Completes Maiden Patrol in South China Sea”, The Diplomat, May 8, 2017.

[17] Nguyen The Phuong And Truong Minh Vu, “Vietnam Coast Guard: Challenges And Prospects Of Development”, Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, January 2017.

[18] “Vietnam’s Fishing ‘Militia’ to Defend Against China”, VOA News, April 18, 2018, https://learningenglish.voanews.com/a/vietnams-fishing-militia-to-defend-against-china/4340613.html.

[19] Andrew Erickson, “Numbers Matter: China’s Three ‘Navies’ Each Have the World’s Most Ships”, The National Interest, February 26, 2018.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ryan Martinson, “The Arming of China’s Maritime Frontier”, China Maritime Report No 2, June 2017.

[23] Ibid

[24] “Al Qaeda Militants Tried to Seize Pakistan Navy Frigate”, The Wall Street Journal, September 16, 2014.

[25] “Al Qaeda’s Worrying Ability to Infiltrate the Pakistani Military”, The Diplomat, September 18, 2014.

[26] “Pak Navy says Air base under Control After Attack”, The Express Tribune, May 23, 2011.

[27] Discussions with senior officers and maritime experts at the National Maritime Foundation, October 2015

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ensuring Secure Seas, Indian Maritime Security Strategy, Naval Strategic Publication (NSP) 1.2, Headquarters, Ministry of Defence (navy), October 2015, P.6, https://www.indiannavy.nic.in/sites/default/files/ Indian_Maritime_Security_Strategy_Document_25Jan16.pdf.

[30] “Jaish Terrorists Training In Deep Sea Diving To Hit Navy Warships“, NDTV, July 18, 2018.

[31]Alan Cummings, “The Mumbai attack – Terrorism from the Sea”, Centre for International Maritime Security, July 29, 2014.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Abhijit Singh, “China’s Three Warfares and India”, Journal of Defence Studies, Volume 7, Issue 4, October 2013.

[34] “China harasses Indian naval ship on South China Sea”, The Times of India, September 2, 2011.

[35] Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui, “Unrestricted Warfare”, PLA Literature and Arts Publishing House, February 1999.

[36] Brahma Chellaney, “A challenging time for the Indo-Pacific”, Livemint, March 18, 2018.

[37] Nora Bensahel, “Darker Shades of Grey – Why Grey Zone conflicts will become more Frequent and Complex”, Foreign Policy Research Institute, February 13 2017.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PDF Download

PDF Download

PREV

PREV