At the 15

th Conference of Parties (COP15) of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), member countries adopted the “Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework” (

GBF) that includes four goals and 23 targets to be achieved by 2030. Although the deal is not legally binding, countries will have to demonstrate progress towards achieving the framework’s goals through national and global reviews.

Among the 23 targets,

Target 3, colloquially known as “30x30,” requires that “at least 30 percent of terrestrial, inland water, and coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem functions and services, are effectively conserved and managed through ecologically representative, well-connected and equitably governed systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures…”

Place-based conservation has usually taken the form of “

Protected Areas” wherein human occupation or at least the exploitation of resources is limited. The definition provided by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in its categorisation guidelines for protected areas has been widely accepted across regional and global frameworks. There are several kinds of protected areas that vary by level of protection depending on the enabling laws of each country or the regulations of the international organisations involved.

Currently, about 17 percent of terrestrial and 8 percent of marine areas are within documented protected and conserved

areas. However, the

quality of these areas has fallen far short of the commitments; less than 8 percent of land is both protected and connected. In the face of such a lacuna, the 30x30 target represents a significant commitment.

Although countries are not individually required to attain the 30x30 target, how countries contribute and demonstrate progress towards achieving the framework’s goals through national and global reviews

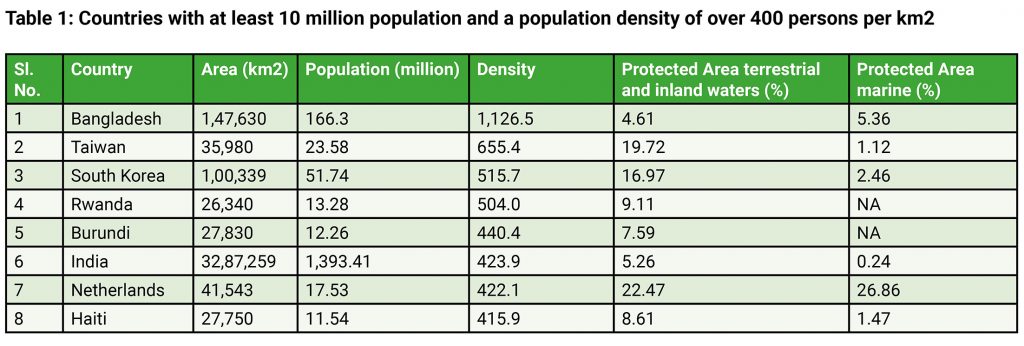

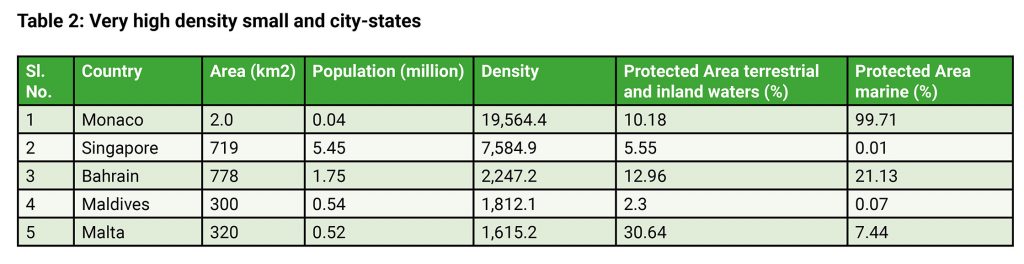

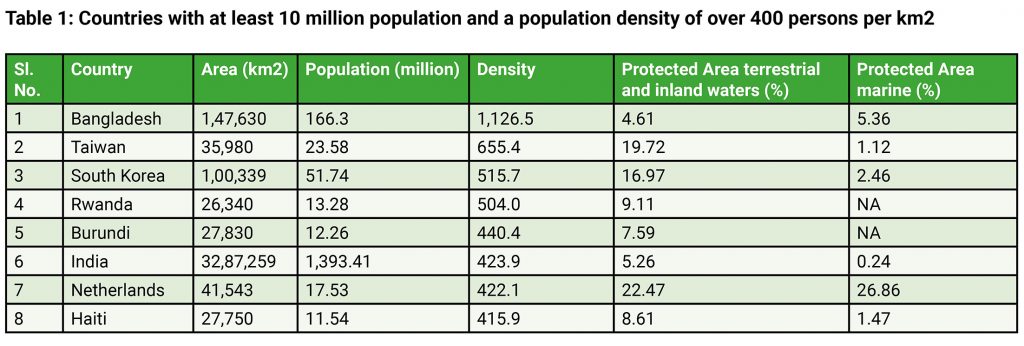

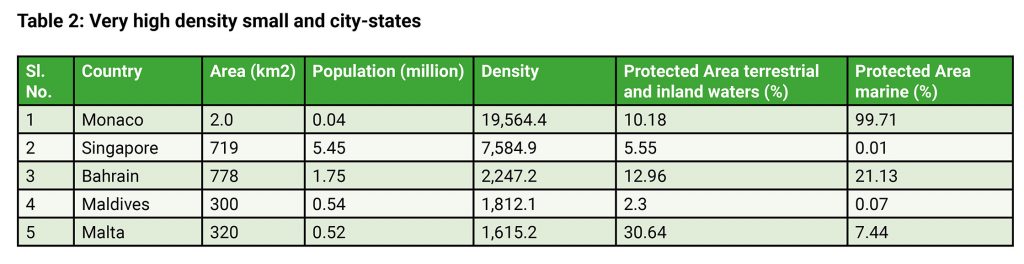

Although countries are not individually required to attain the 30x30 target, how countries contribute and demonstrate progress towards achieving the framework’s goals through national and global reviews, particularly the demographically larger,

densely populated countries of the world (see Table 1), and the very high density small and city-states (see Table 2) is unclear, but a clearer picture has to emerge quickly. The earlier Aichi Targets have remained

unmet.

Table 1: Countries with at least 10 million population and a population density of over 400 persons per km2

Table 2: Very high density small and city-states

Table 2: Very high density small and city-states

Challenges

One of the main challenges will be to improve the quality of both existing and new areas, as biodiversity continues to decline, even within many Protected

Areas. Protected and conserved areas will need to be better connected to each other for movement of species, and for ecological processes to function.

As is evident from Tables 1 and 2, demographically large, high population density countries, and the very high density small and city-states are unlikely be able to bring significant additional terrestrial, inland water, and coastal and marine areas under Protected Area management.

Moreover, species range shifts due to the effects of impacts of climate change will have to be taken into account. Challenges faced by Protected Areas that are experiencing coastal squeeze due to rising sea level on one side, and hard human settlements on the other will also have to be addressed.

The track record of the Global North, thus far, has been poor in meeting its commitments on financial support for climate and biodiversity initiatives.

All of these measures will require significant investments for effective management and community involvement, particularly those areas that harbour megafauna. The track record of the Global North, thus far, has been poor in meeting its commitments on financial support for climate and biodiversity initiatives.

Way forward

Better connectivity

Innovative area-based conservation measures will have to be considered for better connectivity for movement of species – megafauna in particular – between protected and conserved areas. Areas adjoining and or connecting Protected Areas that are not formally managed for conservation will have to be considered for protection; agricultural lands, for example.

Crop depredation often leads to conflict with wildlife but that need not be the case if crop in the identified adjoining area is compulsorily insured against wildlife damage by the state as part of the protection measure. If crop damage is paid for, local communities are unlikely to react adversely to the presence of wildlife. The additional expenditure by the state in developing countries on account of insurance and verification post depredation could be met from the expected financial flows from developed countries of at least US$ 20 billion per year by 2025, and US$ 30 billion per year by

2030. For this purpose, a trust fund under the Global Environment Facility is expected to be established in 2023.

Conservation Development Mechanism

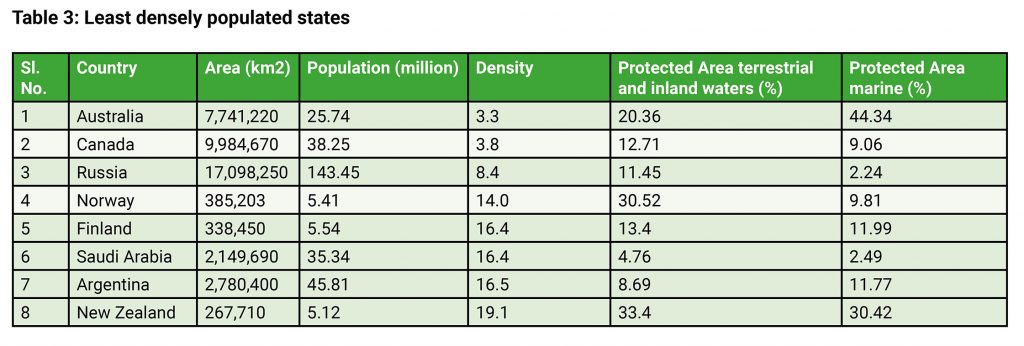

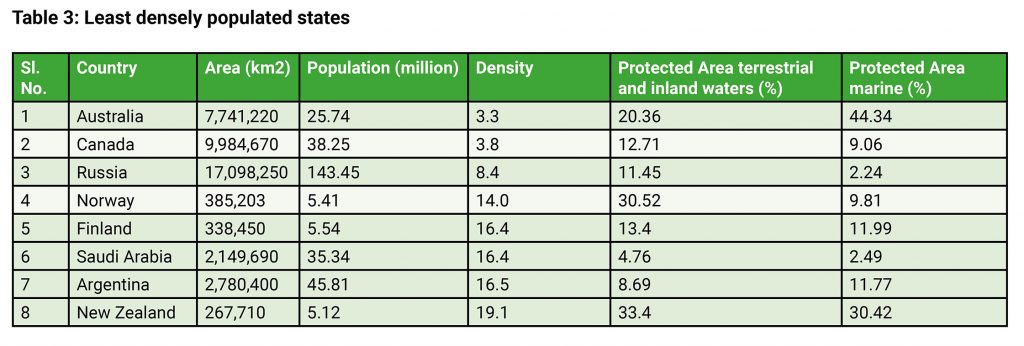

Akin to the Clean Development Mechanism under the climate convention, UNFCCC, a carbon offset scheme allowing countries to fund greenhouse gas emissions-reducing projects in other countries and claim the saved emissions as part of their own efforts to meet international emissions targets, countries referred to in Tables 1 and 2, particularly the economically strong, could invest in biodiversity conservation projects in countries in Table 3.

Table 3: Least densely populated states

Most countries in Table 3 are among the economically strong. These could, as their contribution to global financial flows for biodiversity conservation pay for the economically weaker countries in Tables 1 and 2, besides meeting their own obligations.

Mobile Protected Areas

Innovative management will be required for Protected Areas that are experiencing coastal squeeze due to rising sea level on one side, and hard human settlements on the other. In high altitude and coastal areas, Protected Areas will have to be conceived as mobile rather than static, confined to a set of geographical coordinates. Mangrove and alpine ecosystems for example, will have to be allowed to migrate landward and upward respectively. Issues that are not considered part of conservation measures will have to be included within the ambit of conservation. If the persistence of certain species and their habitats are considered critical, range shifts will have to be accounted for and spaces that are not currently within Protected Area management will have to be secured ex-ante. Competing claims over such spaces will have to be negotiated and resolved as part of the conservation effort.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

At the 15th Conference of Parties (COP15) of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), member countries adopted the “Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework” (

At the 15th Conference of Parties (COP15) of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), member countries adopted the “Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework” (

PREV

PREV