Since the onset of the pandemic, there have been incessant discussions over India’s shape of recovery. From the rapid and optimistic V to the sharp and pessimistic W, conversation on how we will come out of the pandemic has not ceased. Lately, however, there has been a growing consensus that India is actually witnessing a multi-speed recovery, with different sectors of the economy growing at different paces. The issue, however, is that this multi-speed recovery hinges on another alphabetical shape – ‘K’, which could lead to exacerbated inequality in an already unequal India.

The government has been insistent on the V-shaped recovery argument, which is essentially a steep decline in the economic activity and employment, followed by a sharp rise. In the Indian context, this rise can be viewed in terms of increasing demand and business activity with the lifting of nationwide and subsequent state-wise lockdowns. However, it only provides a myopic view of the bigger picture, which illustrates an uneven economic impact of the pandemic on industries as well as workers.

This bifurcation has been reflected in the K-shaped recovery path, wherein, the economy experiences a fall in growth, followed by a split in recovery, where one section of the economy prospers while the other continues to suffer.

As per the data by the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, the Indian economy has shown a significant improvement with 7.5% contraction in Q2 2020-21 as compared an unprecedented 23.9% contraction witnessed in the previous quarter. However, the improvement does not necessarily imply that the recovery path is alike for both formal and informal sectors as the latter is not completely captured in the GDP calculations. On the whole, while the formal sector has recovered relatively steadily, the informal sector has been severely impacted by the pandemic.

The stark contrast is exemplified in the plight of blue-collar workers, who had to migrate on foot to their native places while white-collar workers could work from the comforts of their homes. Additionally, according to a study conducted by Ashwini Deshpande and Rajesh Ramachandran in July 2020, daily wage workers’ rate of job loss was 9 times higher post-lockdown as compared to the pre-lockdown phase.

Besides, there has been a huge discrepancy in the impact of the pandemic and the lockdown even within the formal sector itself. For instance, while the e-commerce sector has registered a 17% growth between February and June 2020 (Unicommerce report), India's hospitality sector declined by 43.5% in terms of revenue per available room in the April-Oct period of 2020 over 2019 (JLL's Hotel Momentum India). Similarly, while, fintech companies in India remain hopeful about their growth, given the structural shift in consumer behaviour towards online solutions (Matrix Partners and McKinsey & Company). On the other hand, the aviation sector continues to function far below its pre-COVID levels due to the cap on operational capacity as well as reluctance of travellers due to potential risks.

Thus, while sectors like pharmaceuticals, technology, e-retail, and software services have fared well during the pandemic, sectors such as tourism, transport, hospitality, entertainment and the like still face the brunt of it.

The bifurcation and uneven recovery are also visible in labour unemployment across formal and informal sectors. Although India faced unprecedented levels of job loss during the lockdown, the unemployment levels have now returned to the pre-lockdown phase. However, India’s recovery in unemployment has not been equal for all, with vulnerable sections being left behind. Besides, these marginalised sections often are majorly employed in the informal sector, which leaves them even more vulnerable to economic downturns like the current crisis.

The aforementioned study by Deshpande and Ramachandran estimated that the rate of job losses among Scheduled Castes, after the lockdown, was three times higher as compared to the upper castes. In another study conducted by Ashwini Deshpande, women employed before the lockdown were 23.5 percentage points less likely to be employed after the lockdown as compared to men employed before the lockdown.

A report by International Monetary Fund warned that the current crisis could follow the path of previous pandemics, which led to higher income inequality and unemployment for people with basic education qualifications while barely impacting employment prospects of people with higher education. Furthermore, a joint report by Asian Development Bank and International Labour Organisation suggests that youth (15-24 years) will face a more severe immediate and long term, economic and social blow as compared to adults (25 years and older) due to the pandemic. The report estimates job losses for 4.1 million Indian youth.

Hence, in a deeply unequal India, a post-lockdown uneven recovery is exemplifying existing inequalities. While the economically and socially better off sectors are experiencing a stable growth, the sectors comprising of marginalised workers and households are undergoing a battle for survival.

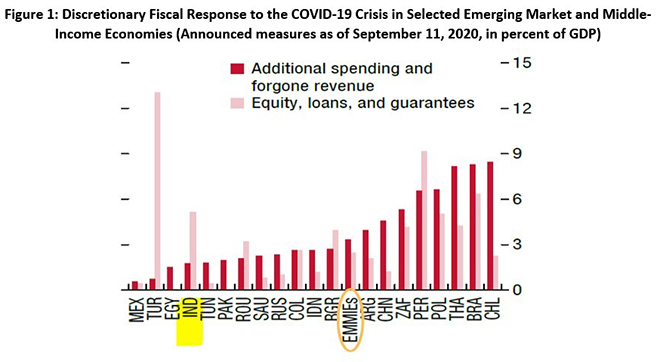

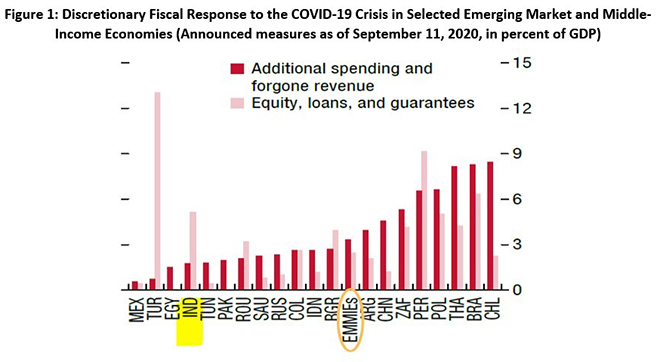

Although the government did provide a timely fiscal stimulus for revival, it has largely proven to be inadequate as compared to other countries. Figure 1 presents a comparison of total fiscal measures undertaken by different emerging market and middle-income countries in the world.

Source: IMF Fiscal Monitor October 2020

Source: IMF Fiscal Monitor October 2020

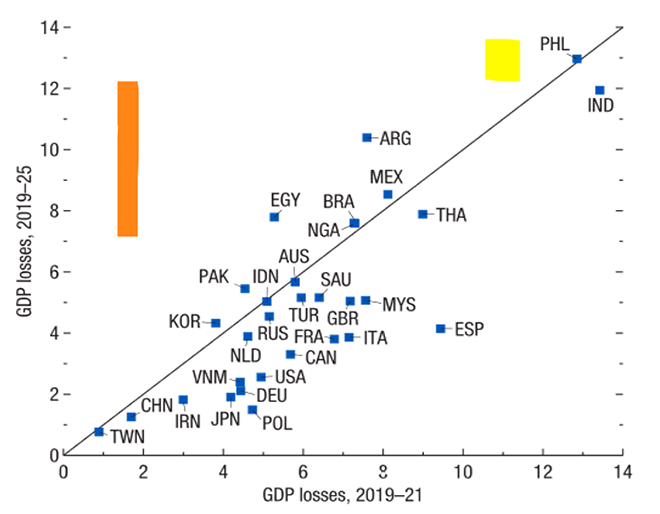

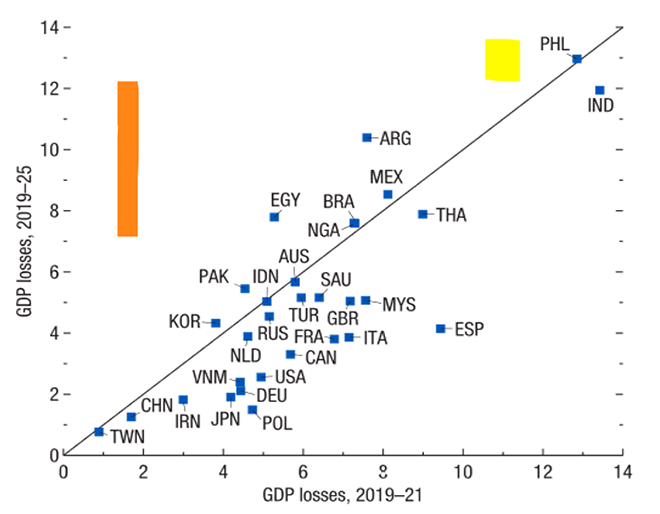

India (highlighted) fares amongst the bottom five and way below the average fiscal stimulus undertaken by the Emerging Market and Middle-Income Economies as a whole (Circled). In the long run, this pattern of growth can prove to be highly detrimental to India as is evident in Figure 2 which highlights the GDP losses to various Advanced and Emerging Market Economies in 2025 as compared to GDP projections made pre-pandemic.

Figure 2: GDP losses: 2019–21 versus 2019–25 (Percent difference between January 2020 WEO Update and October 2020 WEO projections)

Source: IMF World Economic Output Report - October 2020

Source: IMF World Economic Output Report - October 2020

India stands to lose almost 12% of its GDP as compared to pre-pandemic projections– the second worst amongst the selected countries, given its unbalanced recovery.

However, evidence suggests that given the right mixture of expansionary and progressive monetary and fiscal policies, extreme economic downturns like the Great Recession, have successfully transitioned the shape of recovery from K to V. Similarly, India could also adopt policies that target the affected sectors, enabling their speedy revival and paving the way for a balanced growth story.

The recovery of the better-off section often tends to dominate the misery of the weaker section, as has been the case with the current crisis. Instead of turning a blind eye towards the multi-speed recovery of the economy, there is a need to put concerted efforts towards ensuring an inclusive one. The need of the hour, then, is a prompt government response to alter India’s shape of recovery.

This essay originally appeared in The Deccan Herald

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source:

Source:  Source:

Source:  PREV

PREV