While China is celebrating the ‘Year of the Tiger’, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) seems to have resumed its campaign to hunt down the ‘tigers’ of finance. In CCP parlance, tiger is a metaphor for senior cadre, and the Party’s resolve to break the nexus between business groups and officials in the economic bureaucracy seems to have rattled apparatchiks.

Even as China was distracted with festivities to mark the lunar new year, Zhou Jiangyong, the former Party secretary for Hangzhou, was expelled from the Party. The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI)—the Party’s anti-corruption watchdog—has accused Zhou of “

colluding with capital elements” and supporting the “disorderly expansion of capital”.

It is the first instance in which the phrase has made an appearance in a graft case involving a high-ranking CCP official. In December 2020, the Central Economic Work Conference—a conclave of the CCP elite convened to chart the agenda for the nation’s financial sector—resolved to tackle the issue of

disorderly capital expansion. Following this a crackdown began against China’s Big Tech platforms, especially Alibaba. Earlier, Alibaba had been forced to call off its US $35 billion IPO at the last minute by the CCP. It is not a coincidence that the axe has fallen on Zhou who was a top official in Hangzhou, which is also Alibaba’s headquarters. State-controlled media has tied

Zhou’s kin to dodgy land deals.

The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI)—the Party’s anti-corruption watchdog—has accused Zhou of “colluding with capital elements” and supporting the “disorderly expansion of capital”.

Zhou’s expulsion comes close on the heels of the CCDI placing

Wang Bin, head of China Life Insurance (one of the world’s largest insurers) being placed under investigation for corruption. In recent times, China Development Bank—which is supervised by the State Council (China’s cabinet) and finances the CCP’s high-priority projects—has been reeling under a spate of graft convictions and investigations. Prominently, China Development Bank’s former Chief,

Hu Huaibang, received a life sentence for receiving over 85 million yuan (US $13.2 million) in return for helping corporations with loans. Another top China Development Bank official

Zhang Maolong was placed under inquiry in 2021, years after his retirement, by the Party’s anti-graft watchdog.

From the resolutions of the CCDI’s

plenary session in January 2022 attended by General Secretary Xi Jinping, it is becoming evident that his efforts to curb disorderly capital expansion has entered the next level—to ensnare the Party’s elite.

For long, the unwritten rule in the CCP was to let retired cadres ride into the sunset, but the Party’s anti-corruption agency has upturned the norm to

target even retired officials. During the last year, local cadres and their kin have been

under the scanner of the Party in connection with ties to businesses.

Another top China Development Bank official Zhang Maolong was placed under inquiry in 2021, years after his retirement, by the Party’s anti-graft watchdog.

At the anti-graft agency’s January conclave, it got a

new mandate from Xi to sever the nexus between the CCP officials and corporate interests, especially in the financial sector. The collusion between business and the Party has also led to some systemic risks to the economy. From time to time, well-connected businesspeople have been able to secure huge funding. L’affaire Evergrande being a case in point, where the CCP elite had

business stakes in one of China’s largest realty developers. In turn, the CCP felicitated Evergrande founder Xu Jiayin as an ‘outstanding private entrepreneur’, and ensured an unlimited pipeline to funds that led to the realty giant becoming one of the most indebted entities with a burden of US $300 billion liabilities.

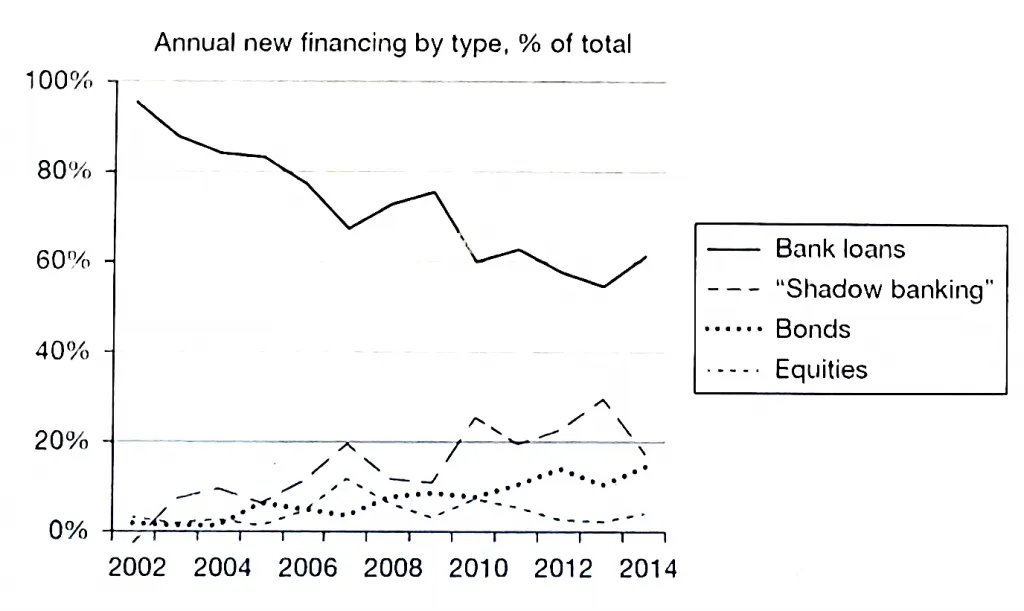

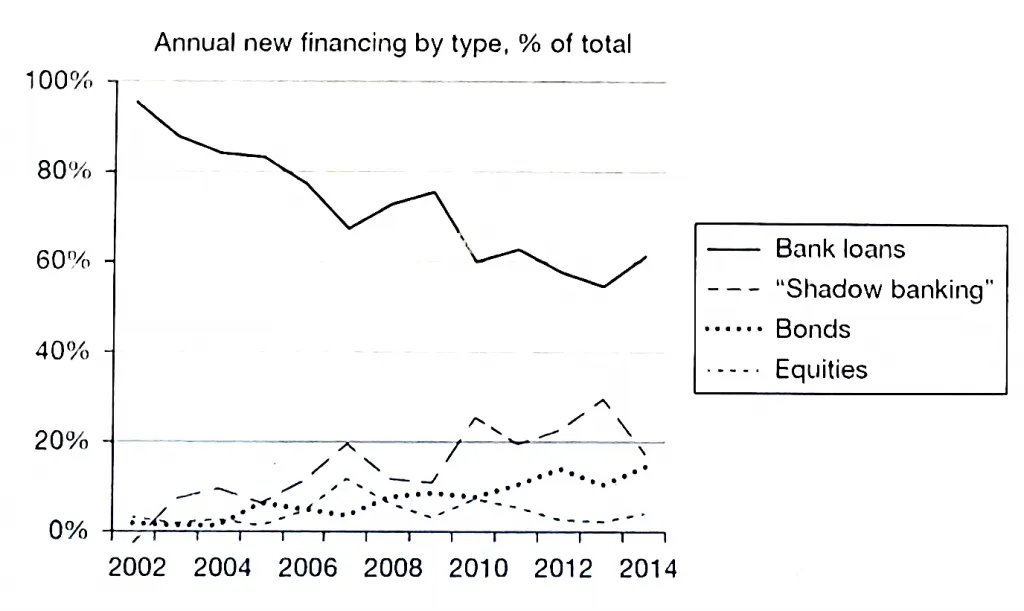

The banking sector is key to economic growth in China as more than 60 percent of the finance is provided by banks whereas only 20 percent comes from issuance of shares and bonds.

China’s Economy: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 128.>

China’s Economy: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 128.>

This increases the importance of the apparatchiks in the financial sector for business interests. Alternatively, these tigers of finance could also be used by groups inimical to Xi Jinping within the CCP to build a war chest to present a challenge to him.

The CCDI is now being tasked with investigating the collusion between tech platforms and influential elements of the CCP, which have led to creation of monopolies. There seems to be a significant revaluation in the CCP’s thinking from looking at corruption solely as a social evil, and tech platforms as mere wealth creators.

Writing in the CCP’s journal ‘

Qiushi’ in January 2022, Xi underlined the new line of thought that while the fast expansion of China's economy had undoubtedly transformed social media networks, IT firms, and the digital economy, but “unhealthy” developments that flouted rules threatened its economic and financial security.

The CCDI is now being tasked with investigating the collusion between tech platforms and influential elements of the CCP, which have led to creation of monopolies.

There is a view in the CCP that some tech companies have obtained disproportionate clout as some of their services have become a facet of public goods. The fear is that the corporate groups will leverage their authority to pose a challenge to the CCP. These are not just conjectures; the CCP seems to have drawn lessons from the discomfiture of former US President Donald Trump, who was blackballed by social media networks in the run-up to the 2020 Presidential Election. Closer home, Alibaba’s Jack Ma was openly critical of CCP’s governance during the 2020 Bund summit in Shanghai, where the nation’s power elite and top bankers had congregated. Such apprehension is openly being voiced by academics.

Wu Xinwen, a professor at Fudan University in Shanghai, warns that China’s business elite has acquired economic might and are eager to convert it into political power with assistance from some elements in the CCP. This means that there are some who may be opposed to Xi’s unrestrained authority, especially now that he has indicated his intent to be crowned ruler for life.

To conclude, for a long time Xi had spoken about the need to defuse ‘financial risks’, a euphemism for the debt crisis in China’s banking sector. Now, the CCP’s efforts to clean the banking sector seem to have commenced in earnest with the China's Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission in 2021 writing off

‘bad assets’ to the tune of US $490 billion—a record in recent times. This gives the CCP a more real picture of the banking sector. Second, since the era of opening up of the Chinese economy, cadres who worked in its economic technocracy had a carte blanche. Those like Zhu Rongji, who was the governor of China’s central bank, went on to become the state premier—No. 2 in the CCP hierarchy. He was instrumental in getting CCP conservatives on board with respect to China’s entry into the World Trade Organisation, which it eventually achieved in 2001. From the language of the CCDI’s January plenum, bodies like the anti-graft agency seem to have risen in the CCP’s warrant of precedence. The man Xi chose to head the CCDI from 2012 to 2017, Wang Qishan, is China’s current Vice-President.

Such apprehension is openly being voiced by academics. Wu Xinwen, a professor at Fudan University in Shanghai, warns that China’s business elite has acquired economic might and are eager to convert it into political power with assistance from some elements in the CCP.

The CCDI’s rise in China’s governance structure poses a new challenge. If the economic bureaucracy is under intense scrutiny, then it may affect disbursal of genuine loans to enterprises. The CCDI’s mandate to sever the nexus between ‘power’ and ‘capital’ and the institution of a register to

blacklist bribe-givers mean that private companies will be in the CCP’s crosshairs. In such a situation, while Xi may get the satisfaction of stamping his imprint on the Party, it may come at the cost of scuppering the investment climate in China.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

While China is celebrating the ‘Year of the Tiger’, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) seems to have resumed its campaign to hunt down the ‘tigers’ of finance. In CCP parlance, tiger is a metaphor for senior cadre, and the Party’s resolve to break the nexus between business groups and officials in the economic bureaucracy seems to have rattled apparatchiks.

Even as China was distracted with festivities to mark the lunar new year, Zhou Jiangyong, the former Party secretary for Hangzhou, was expelled from the Party. The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI)—the Party’s anti-corruption watchdog—has accused Zhou of “

While China is celebrating the ‘Year of the Tiger’, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) seems to have resumed its campaign to hunt down the ‘tigers’ of finance. In CCP parlance, tiger is a metaphor for senior cadre, and the Party’s resolve to break the nexus between business groups and officials in the economic bureaucracy seems to have rattled apparatchiks.

Even as China was distracted with festivities to mark the lunar new year, Zhou Jiangyong, the former Party secretary for Hangzhou, was expelled from the Party. The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI)—the Party’s anti-corruption watchdog—has accused Zhou of “

PREV

PREV