This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

In 2007,

Time magazine featured a story on Mr Tulsi Tanti, wind energy pioneer and Chairman & Managing Director of the Suzlon group, who passed away suddenly this month (October 2022). As part of a series on ‘Heroes of the Environment’, the story offered two reasons behind Mr Tanti’s entry into the Indian wind energy industry. One was the

poor quality and high price of grid-based power that affected the profitability of his textile yarn business. The second was a report on climate change that predicted that without a radical decrease in the

world's carbon emissions, many parts of the world would be underwater by 2050. Both factors continue to drive investment in renewable energy (RE) by the industry today.

The industry is now facing the headwinds of cost escalation, competition from cheaper solar photovoltaic (PV) power and policy attention devoted to the solar sector.

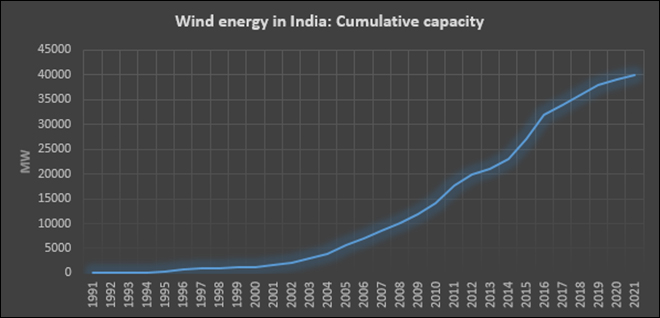

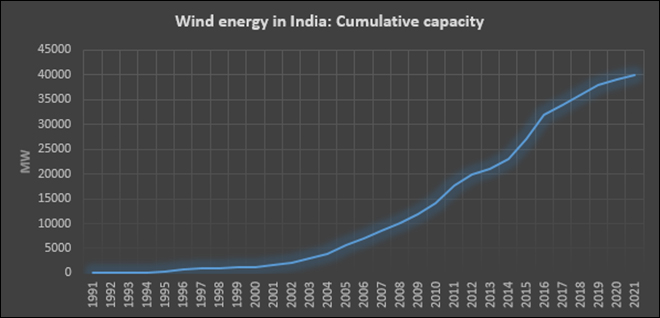

When Mr Tanti entered the Indian wind energy industry, the total installed capacity was about 500 MW (megawatt). In August 2022, total wind energy capacity was

over 41 GW (gigawatts), a CAGR (compound annual growth rate) of over 14 percent. But the tailwinds that propelled the Indian wind energy industry from the late 1990s until the early 2010s have died down. The industry is now facing the headwinds of cost escalation, competition from cheaper solar photovoltaic (PV) power and policy attention devoted to the solar sector. Suzlon’s own history is a testimony to the rise and stagnation of the Indian wind energy industry. In the 2000s, the growth and

success of Suzlon enabled its founder to become an international hero of the environment. Today the company characterises

travails of the wind energy sector.

Tailwinds

India’s wind energy journey is essentially India’s RE journey. In 1982, the

Department of Non-conventional Energy Sources (DNES) was constituted under the Ministry of Energy. Based on an assessment of wind energy potential in India by the Indian Institute for Tropical Metrology, DNES supported the commissioning of the first grid-connected wind turbine of

40 kW (kilowatt) capacity at Gujarat in 1984. Later DNES offered grants to five projects of 550 kW. In 1987, the Renewable Energy Development Agency (IREDA) was established to act as a dedicated public sector financing arm for RE projects.

In 1988, the Danish aid agency

DANIDA supported plans to develop two commercial projects of 10 MW (megawatt) each in the states of Gujarat and Tamil Nadu. These DANIDA-sponsored projects were the first demonstrations of large-scale grid-connected wind farms. These demonstration projects provided real data on the techno-economic feasibility of wind energy generation in India that

initiated private sector interest in wind energy generation. Favourable policies by the government also played an important role in garnering private investment in both the manufacture of wind turbines and wind energy generation. These included but were not limited to: a)

100 percent accelerated depreciation on capital investment in equipment in the first year of installation; b) Five years’ income-tax exemption on income from the sale of power generated by wind energy c) mandatory purchase of electricity by State Electricity Boards (SEBs) d) industry status to wind equipment manufacturers. In 1992, DNES became the

Ministry of non-conventional energy sources (MNES). MNES set targets for RE generation based on incentives for capacity addition.

Captive wind power generation fixed one of the major components in the cost of production of textile yarn which, in turn, improved the profitability of textile mills.

One of the lesser-known drivers of the wind energy sector was the

technology upgradation fund (TUF) launched by the Ministry of Textiles in 1999 to facilitate the modernisation and technology upgradation of jute and textile mills over a period of five years. The scheme

continues to be operational with modifications and adaptations even today. When first initiated, TUF provided loans at commercial rates to assist the textile industry's modernisation, including gaining access to firm supplies of power by investing in their own power plant. In Tamil Nadu, home to at

least half of India's textiles market, the TUF scheme was boosted further by the state government's decision to introduce a special lending rate of 12.5 percent for wind projects supplying power directly to the textile company. As the textile industry was power intensive, investment in wind energy generation for captive consumption made economic sense. Captive wind power generation fixed one of the major components in the cost of production of textile yarn which, in turn, improved the profitability of textile mills. This historical policy push to wind power generation by the state government along with the fact that

Tamil Nadu has one of the best windy coastal areas explains why it leads all other states in cumulative installed wind energy capacity and also in annual capacity additions.

The provision of an

accelerated depreciation mechanism within the context of the income tax act was another significant driver of growth in the wind energy segment.

Accelerated depreciation allowed the investor (such as a textile company) to divert taxable income into a wind power project which acted as a tax shield. With accelerated depreciation, investors could show the allowed

depreciation value as deductible from income in the first year of investment thus avoiding the tax that would be levied on that amount.

Accelerated depreciation led to negative outcomes such as large textile and cement industries

appropriating all the tax benefits as they were large investors in technology. These industries also made hasty decisions around the time of tax filings to install wind plants. This resulted in

poor siting and low or no generation by wind generators. These outcomes eventually led to the scaling down and phasing out of accelerated depreciation.

Wind energy also benefited from incentives like

renewable purchase obligations (RPOs), attractive rates for

feed-in-tariff along with capital subsidies that continue in one form or the other even today.

Headwinds

The tailwinds behind wind energy in India began to ebb when the market-oriented

electricity act was introduced in 2003. Though the act stipulated special treatment for RE resources, the act-initiated market-based discipline on the electricity sector that indirectly influenced RE projects. In 2006, MNES was recast with the more progressive title of

Ministry of New & Renewable Energy sources (MNRE) to resonate with the global narrative of climate change as a key challenge and RE as the solution. The national tariff policy announced that year emphasised the importance of setting targets for RE capacity addition and stressed the importance of preferential tariffs for RE power. In 2009,

generation-based incentives (GBI) for RE generation replaced policies that supported RE capacity addition rather than generation. In the late 2000s, the success of reverse auctions in driving down solar tariffs led the wind energy sector to adopt the model. Initially, it was welcomed by the wind sector but eventually, the sector began crumbling under the

constant pressure to lower tariff that was not consistent with the increase in the price of steel and other wind energy components.

The national tariff policy announced that year emphasised the importance of setting targets for RE capacity addition and stressed the importance of preferential tariffs for RE power.

In 2014, targets for RE capacity were increased by

almost five-fold. The increase in targets for RE has meant a large degree of centralisation of the initiatives and programmes to increase RE capacity. Centralisation of decision-making has produced mixed results. On the one hand, it has dramatically improved the visibility of India’s effort to decarbonise the power sector. This has attracted large overseas players and foreign investment in the RE sector. On the other hand,

centralisation has oversimplified and generalised RE projects offered on auction or tender basis which has affected their technical and economic viability. Whilst the involvement of technologically competent international players in the RE sector has introduced advanced technology, it has also driven out small players with domestic roots, especially in the wind sector. Most importantly the constant pressure to drive down tariffs on RE projects has favoured large international players with access to low-cost finance at the expense of smaller domestic players.

In addition, the overemphasis on lower tariffs has meant that tariff caps set for centrally auctioned projects are often too low to make the projects bankable or economically viable. The case of the Indian wind energy industry which has developed domestic manufacturing capabilities over the last 30 years illustrates the challenge.

Four thousand small and medium enterprises (SMEs) that manufacture equipment and components for the wind energy industry employ 2 million people directly or indirectly. These industries and jobs are now under threat as the downward pressure on tariffs has pushed many wind SMEs to the verge of bankruptcy.

Whilst solar is generally location agnostic, wind favours specific locations and this has become a major problem when tariff caps are set at low levels. Under a ‘one tariff fits all’ approach that centralised efforts pursue, wind projects crowd around a few favourable locations around the country. This has limited capacity creation. Continued emphasis on low tariffs pushed projects towards cheaper components that compromised the efficiency and life of wind energy systems. It has also contributed to the creation of stranded assets that drain public finances replicating the plight of some of the conventional power generation projects. In 2001, the capital cost of wind projects in India was estimated at about

INR30 million/MW compared to

INR300 million/MW for solar projects. By 2020, the capital cost of solar projects had fallen to about

INR55 million/MW whilst the capital cost of wind increased to about

INR60 million/MW. The modular nature of solar projects adds to the attractiveness of solar compared to wind projects. Between 2016 and 2022, wind energy capacity addition has grown at a

CAGR of about 5 percent. To meet the target of 140 GW wind energy capacity by 2030, the growth rate in capacity addition has to triple. The government's decision in July 2022 to

end reverse auctions for RE projects may ease price pressure but it is likely to bring out new problems such as the competitiveness of RE power.

Source: MNRE

Source: MNRE

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This article is part of the series

This article is part of the series

PREV

PREV