In the early days of September, 2015, students from universities across Delhi woke up to the bold colourful words ‘Pinjra Tod’, literally meaning, ‘break the cage’, sprawled across their campuses. Pinjra Tod, a campaign that originally started from a Facebook page, gained recognition when Jamia Millia Islamia (JMI), a minority institution, issued a circular prohibiting girls from going out at night. That came about to be the formation of Pinjra Tod, an autonomous student-run collective effort from Delhi University (DU), JMI, Ambedkar University and Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU).

Women from universities took to streets and campaigned against unreasonable restrictions on their mobility, reclaiming space extended from the exterior to the interior. Girls protested against moral policing in the name of concerns and decided to not be told how they should carry themselves and their body. Thus, it became the idea of reclaiming their body in the process. Countless women came out on social media and shared their bitter experiences of times they had been infantilized, moral policed and discriminated against, all in the name of gender, by guards, wardens, principals and the like. They filed a 45-page report to the Delhi Commission of Women (DCW) in November 2015. Within days, the JMI received a notice from the DCW questioning the basis of such a restriction. This was the first victory of the movement, however minor, where they refused to be infantilized yet again by the authorities.

Source: gypsyaabha

Source: gypsyaabha

Now a little over two years since its inception, it has grown into a wider campaign which claims to be battling against patriarchal and caste-ist structures which constantly seek to regulate and control women’s lives, sexuality and mobility through wide ranging mechanisms. A movement that initially started to push curfew hours has challenged the way in which women’s freedom is restricted in the name of safety. The movement has also been successful in bringing to light other forms of caste and class based discrimination such as accommodation problems for women from lower caste and discrimination within hostels and PGs. These two issues -- namely of mobility and caste based discrimination -- are part of Brahmanical institutions that organise identities around caste and specific notions of ‘femininity’. Pinjra Tod has become a unique movement for its response to and challenge of caste based patriarchy. “They have localised the movement to reflect South Asian patriarchy, which ties in with elements of caste, class and the politics of reproduction,” says feminist historian Uma Chakravarti. It is this idea of Brahmanical patriarchy that I would like to explore.

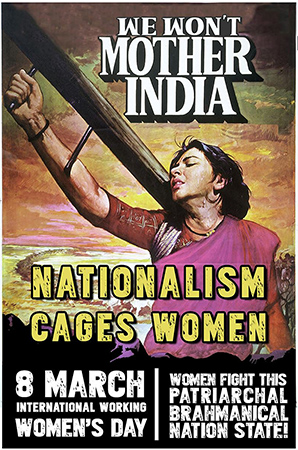

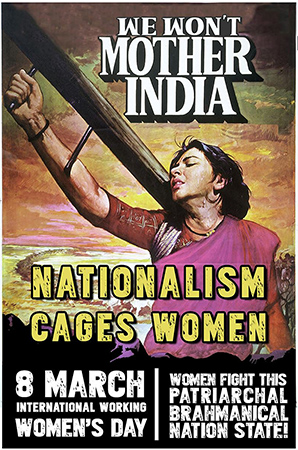

Source: Pinjra Tod

Source: Pinjra Tod

The root of patriarchal society is the ideology of male domination and the consequent repression of women. This concept of male domination, especially in the Hindu society, was given birth through the concept of the caste system. The caste system divided the society into four castes (varnas) in the ascending order -- Brahmans, Kshatriyas, Vaihways and the Shudhras. Thus, Brahmans were at the top of the pyramid and enjoyed complete control over the society. It is through this social order that Brahmanical patriarchy came into existence and continues to this day. Brahmanical patriarchy sustains the varna hierarchy and inequality through two methods; it controls the sexuality of women and exerts economic and political control.

Louis Dumont (1972) defines caste system as a system of consensual values; a set of values accepted by both dominant and dominated. The power is thus confined to a selected few in this debilitating power structure. Family structure and patterns of kinship are tied to the institution of caste. In the caste system, the fact that membership of discrete and distinct groups is defined by birth entails a concern with boundary maintenance through regulation of marriage and sexual relations. Thus, the onus of boundary maintenance falls on women because of their role in biological reproduction.

The most critical stage of a woman’s life is when her body has acquired a capacity to reproduce but she has no authority to do so. Thus the phase is characterised by restrictions on her movements. As Uma Chakravarti argues, women have been traditionally seen as upholding the structure of marriage, sexuality and reproduction; it becomes important to control their movements to uphold the caste system. Their role to marry within the caste system and any digression is impermissible. This strict following of the caste system, to keep the blood pure, is the reason why women’s mobility and sexuality have been under the constant surveillance of the patriarchy.

https://twitter.com/WomenBuzz/status/845873646883221504

Following the caste structure is the epitome of Hindu society. Women are brought up internalising the concept of ‘pavitrata’ or ‘purity’. It is this inequality on the basis of assumed ritual purity that perpetuates the caste system. We thus witness women’s compliance to Brahmanical social order by subjecting themselves to the control of Brahmanical patriarchy. Following this is the hegemonic Brahmanic notion of ‘femininity’. These notions of femininity are ascribed to women in light of their emergent sexuality and prospective motherhood; motherhood being the highest achievement in a woman’s life. The phenomenon of boundary maintenance is a crucial element of the caste system, and hence young vulnerable girls must be protected by putting emphasis on purity and restraint in behavior.

Considerable importance is attached to the way a girl carries herself. If a girl’s sexuality is seen an ‘unfeminine’, they can bring the contours of the body into greater prominence and attract attention. Thus, to establish her femininity, girls must avoid masculine demeanour and behavior. It is the fear of being maligned as a girl of bad character which a girl must try to avoid. The incidents that came into focus during the Pinjra Tod campaign, of moral policing seek to reinforce certain notions of the ‘good’ and ‘obedient’ woman who talks ‘politely’, wears ‘decent’ clothes, does not ‘question’ the authorities or indulge in transgressive ‘relationships’; all activities ascribed to ‘loose’ women. Thus, institutions which are the place for liberation of women where they are supposed to learn and grow, instead become spaces which end up reinforcing and strengthening these patriarchal and caste-ist norms and practices. Thus there exists a complex relationship between gender and caste.

Source: SINGHSHISH

Source: SINGHSHISH

This also questions the myth of patriarchy as a ‘monolithic’ concept and challenges the category of ‘women’ as a monolithic identity. As seen above, it is mostly the upper caste women’s compliance in maintaining the Brahmanical social order. There is thus a necessity to question the ‘difference’ in patriarchy as in the case of third world and Dalit feminists. Pinjra Tod also sheds light on the issue of discrimination against women from lower castes who were discriminated not only on the basis of gender, but their caste. Their struggles are different from that of an upper caste woman, where they not allowed accommodation in PGs because of being ‘impure’; a notion entrenched in the varna system.

Source: kh_Ibrar82

Source: kh_Ibrar82

Another important point is that of economic control. Gail Omvedt talks about caste as a material reality with a material base (Chakraborty, 2003, p.12) and economic inequality. Having been subordinate to the upper castes, they were never allowed equal economic opportunity and thus also belong to the lower class. The rise in fee hike for women hostels, like in Hindu college, was thus more unreasonable to those belonging to the lower caste and class. Women from the lower rungs of society do not just have to fight for their freedom in terms of mobility, but also economic independence.

Pinjra Tod thus brought to light multi faceted issues related to the complexity of gender and caste. Just like Nivedita Menon argues in her book

‘Seeing like a Feminist’, they advocate that a public space becomes safe for women if more women step out at night. Instead of them being locked up at home after dark, for no fault of theirs, they should be stepping out together and reclaiming the right as is theirs. More importantly, culture and tradition, no matter how patriarchal, are characterised by inertia. It is difficult, albeit impossible to eradicate it. Subversively challenging it and gradually changing it is our best bet.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

In the early days of September, 2015, students from universities across Delhi woke up to the bold colourful words ‘Pinjra Tod’, literally meaning, ‘break the cage’, sprawled across their campuses. Pinjra Tod, a campaign that originally started from a Facebook page, gained recognition when Jamia Millia Islamia (JMI), a minority institution, issued a circular prohibiting girls from going out at night. That came about to be the formation of Pinjra Tod, an autonomous student-run collective effort from Delhi University (DU), JMI, Ambedkar University and Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU).

Women from universities took to streets and campaigned against unreasonable restrictions on their mobility, reclaiming space extended from the exterior to the interior. Girls protested against moral policing in the name of concerns and decided to not be told how they should carry themselves and their body. Thus, it became the idea of reclaiming their body in the process. Countless women came out on social media and shared their bitter experiences of times they had been infantilized, moral policed and discriminated against, all in the name of gender, by guards, wardens, principals and the like. They filed a 45-page report to the Delhi Commission of Women (DCW) in November 2015. Within days, the JMI received a notice from the DCW questioning the basis of such a restriction. This was the first victory of the movement, however minor, where they refused to be infantilized yet again by the authorities.

In the early days of September, 2015, students from universities across Delhi woke up to the bold colourful words ‘Pinjra Tod’, literally meaning, ‘break the cage’, sprawled across their campuses. Pinjra Tod, a campaign that originally started from a Facebook page, gained recognition when Jamia Millia Islamia (JMI), a minority institution, issued a circular prohibiting girls from going out at night. That came about to be the formation of Pinjra Tod, an autonomous student-run collective effort from Delhi University (DU), JMI, Ambedkar University and Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU).

Women from universities took to streets and campaigned against unreasonable restrictions on their mobility, reclaiming space extended from the exterior to the interior. Girls protested against moral policing in the name of concerns and decided to not be told how they should carry themselves and their body. Thus, it became the idea of reclaiming their body in the process. Countless women came out on social media and shared their bitter experiences of times they had been infantilized, moral policed and discriminated against, all in the name of gender, by guards, wardens, principals and the like. They filed a 45-page report to the Delhi Commission of Women (DCW) in November 2015. Within days, the JMI received a notice from the DCW questioning the basis of such a restriction. This was the first victory of the movement, however minor, where they refused to be infantilized yet again by the authorities.

Source:

Source:  Source:

Source:  Source:

Source:  Source:

Source:  PREV

PREV