Energy has, no doubt, become an essential strategic component of bilateral equations. This is because energy security is not only a crucial foreign policy goal, but is tied inextricably to a nation’s larger security concerns. As India and Maldives look to become energy partners, it is important to consider the specific ways in which they can address each other’s energy challenges. It is further useful for India to understand energy security from the specific point of view of a small island nation.

As the world sees a burgeoning demand for energy in the years to come, along with reserves of conventional fossil fuel becoming critically depleted, there will be increased competition for energy resources underpinned by other forms of competition and rivalry between nations, particularly the great powers. Energy diplomacy will become interlinked with other kinds of diplomacy pertaining to trade, environment and development assistance. Being one of the top energy importers, India understands this acutely and is investing in engaging potential future energy partners.

The goal is to mitigate risk, whether geopolitical, environmental, on the supply side, or to do with price stability.

Energy security refers to the ability to ensure the reliability of energy supply flows at stable and affordable prices. The goal is to mitigate risk, whether geopolitical, environmental, on the supply side, or to do with price stability. There are many dimensions to a country’s desire for energy security, depending on where it sits on a world map, what stage of development its economy is at and whether it’s a supplier or a consumer of energy. Demographics, size, material capabilities, availability of energy resources, technical expertise, human resource development and several other attributes, further add layers of complexity to the challenge of energy security.

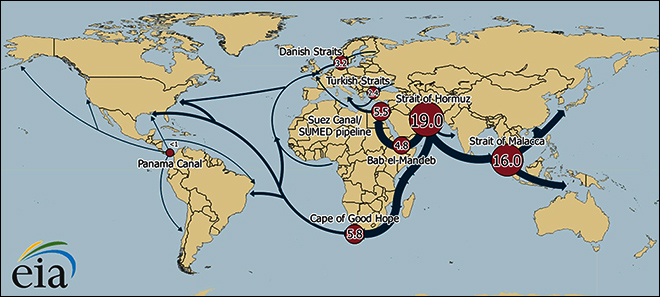

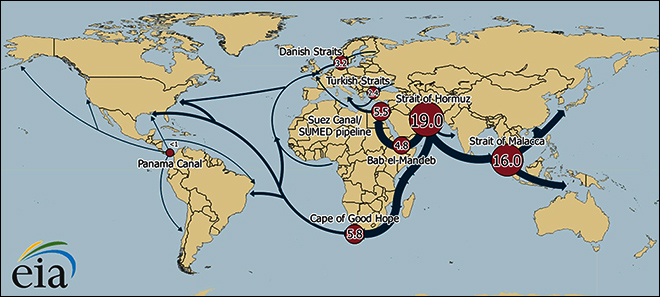

Chokepoints

Considering that much of the world continues to depend on fossil fuels, there is a strong maritime component to energy security. Disruptions to supply lines occur for various reasons such as piracy or natural disasters, extreme weather conditions like tsunamis and floods, as well as global pandemics as we have been witnessing recently. These delays lead to higher shipping costs and an invariable spike in prices, whether directly or indirectly. However, geopolitical tensions are what make nation states most wary. Supply routes are particularly vulnerable to chokepoints that can be easily blockaded in times of crisis, such as the Malacca Straits, Sunda Strait, Lombok Strait and Straits of Hormuz, amongst others.

Helping to address Maldives’ energy concerns is a step in the right direction for India’s own goals of energy security.

How to mitigate undue exposure to chokepoints, either through maintaining a presence (the US in Diego Garcia) or circumnavigating them (China and Gwadar Port) will remain an important aspect of energy security. The Strait of Hormuz and the Strait of Malacca are the world’s most important strategic chokepoints by volume of oil transit. Acutely aware of its location, referred to by maritime strategists as a “toll gate” between these two chokepoints, the Maldives positions itself as an important energy partner amidst great power rivalry in the Indian Ocean. Helping to address Maldives’ energy concerns is a step in the right direction for India’s own goals of energy security.

Daily transit volumes (in million barrels) through world maritime oil chokepoints

Source: US Energy Information Agency (Based on 2016 Data)

Source: US Energy Information Agency (Based on 2016 Data)

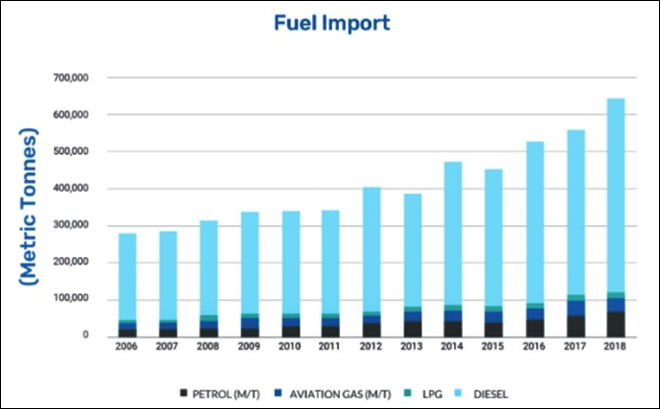

Reliance on imports

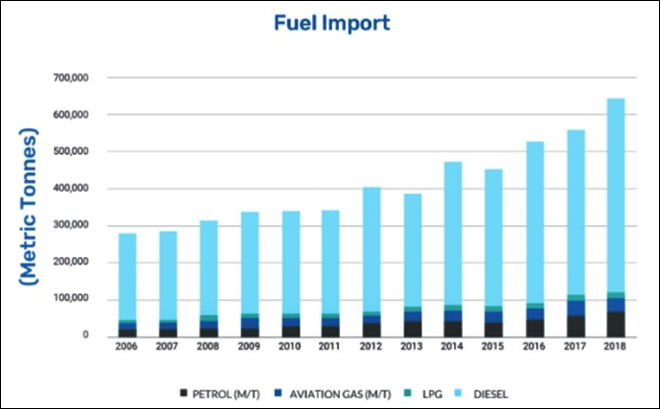

Overdependence on imports is a vulnerability from the point of view of energy security. However, energy independence through increasing domestic production is not an easily achievable goal particularly for small island developing states or SIDS as they are commonly known. Instead, SIDS need to find ways to mitigate the risk posed by high dependence on imports through a multi-pronged approach. Maldives has no proven fossil fuel reserves, i.e., oil or gas, so its energy needs are almost entirely met by imports.

FUEL IMPORTS: Energy Mix (Approximate)

| DIESEL 82% |

| LPG 2% |

| AVIATION FUEL 6% |

| PETROL 10% |

Source: The Maldives, Ministry of Energy

In 2018, energy imports to Maldives totalled 643,900 tonnes and consisted of aviation fuel, diesel, petrol and Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG), with diesel being its major import at nearly 80% of total fuel imports. The International Energy Agency (IEA) recommends, “energy security for a small island nation such as Maldives can only be achieved through diversification of the country’s energy resources to reduce dependence on imported fuels.” Increasing the supply of energy from renewables, installing solar panels, exploring alternatives such as wind, ocean current, wave and even waste energy are, therefore, crucial steps.

Source: The Maldives, Ministry of Energy

Source: The Maldives, Ministry of Energy

Energy storage

An alternative to mitigating the vulnerabilities associated with imports is to have better energy storage. This must be addressed across all energy types. For solar power, it would be batteries, but the challenge here is that they are prohibitively expensive. For oil, developing a reserve stock is an option. India through its energy partnership with the US is exploring the possibility of storing oil in the US to increase its strategic oil stockpile (though admittedly this is not without its challenges) as well as exchange of information and best practises on how to operate and maintain strategic petroleum reserves. The Maldives Energy Policy and Strategy (MEE 2016) similarly explored the alternative of regional oil bunkers in four locations in the northern parts to store oil in times when the world oil prices drop. India should support such initiatives.

Storage must be addressed across all energy types.

Environmental concerns

Today there is an embrace of a broader definition of energy security, one that considers the environmentally damaging effects of energy consumption, particularly from fossil fuels. Nation states face a two-part challenge, how to meet the short-term challenge of providing their populations with energy services while addressing the long-term goal of a zero-carbon economy. For SIDS, this will remain their most important goal. For India, as it addresses the many dimensions of its energy security goals, its biggest challenge will be addressing the presence of coal in its energy mix. Energy goals cannot be addressed one after the other, such as energy access first and climate change later. India needs to have an integrated approach as well as support its SIDS neighbours in doing the same.

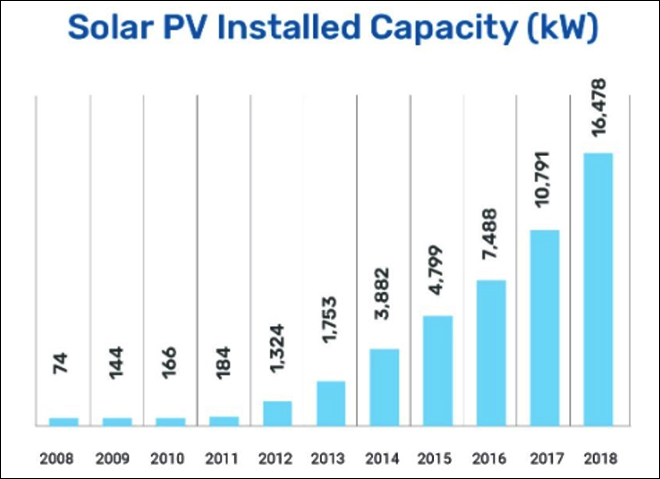

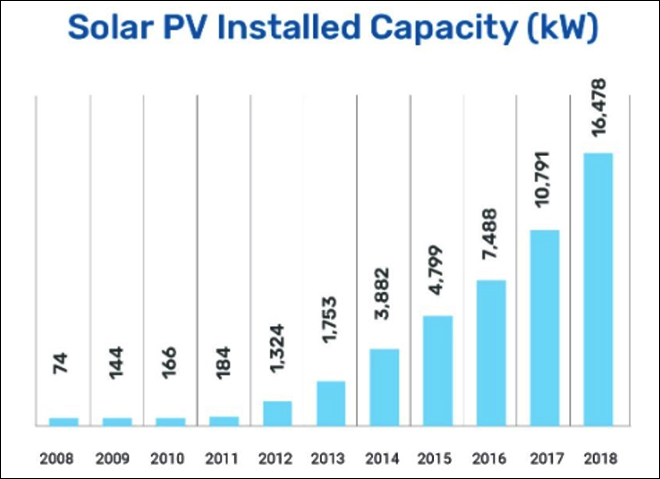

Moving towards locally sourced, greener energy has been a priority for the Maldives for some time now. Its National Policy and Strategy Plan of 2010 called for investing in the green sector by increasing substantially the share of renewable energy. The Minister for Environment, Dr Hussain Rasheed Hassan, recently stated, “The Maldives’ energy sector is firmly transitioning to an environmentally-friendly sector by adopting renewable energy.” Renewable energy addresses the twin goals of contributing energy security as well as reducing carbon emissions.

Energy goals cannot be addressed one after the other, such as energy access first and climate change later.

Solar panels

Source: The Maldives, Ministry of Energy

Source: The Maldives, Ministry of Energy

Due to the abundance of sunshine in the Maldives, installing solar PV panels is a significant step towards energy security. As India offers support to the Maldives’ green energy plan, particularly future cooperation in solar projects, it needs to take into account the many associated challenges of solar energy in an island nation. One major challenge is the lack of land when it comes to small islands. Floating solar panel projects have been undertaken in the Maldives; their drawbacks, however, need to be studied closely.

With SIDS the challenge of energy security does not end with a policy of switching to renewables. It includes building support infrastructure that is both sustainable and resilient in the long term. Unlike big countries like India, for SIDS, even heavy rainfall can damage critical energy infrastructure. A review done on the installation of a solar diesel system at Mandhoo island in the Maldives showed that a lightning strike damaged the electronic circuits. Similarly, another study found that natural disasters that affect SIDS very often destroy distribution infrastructure and rebuilding takes a long time. The appliance on Mandhoo islands was French-made and it took several months to get it replaced.

Floating solar panel projects have been undertaken in the Maldives; their drawbacks, however, need to be studied closely.

A study by UNDP recommended that future projects should consider regional providers of appliances in order to avoid extended shipment time and expenses. India must consider building a regional network of suppliers closer to the Indian Ocean. Lightning control measures, including a contingency plan for rebuilding also need to be considered for renewable energy installations.

Human resource development

Another challenge that needs to be addressed in the Maldives is one of human resource development. On most islands, there is a lack of trained electrical engineers who have the technical expertise needed to deal with new technologies. For long term sustainable energy security, human resource capacity needs to be enhanced by providing continuous training. Switching to renewables in order to reduce the dependence on imports, while remaining dependent on outside help for infrastructure repairs, technical knowledge and capacity does not solve the energy security problem.

Inequality challenge

The human resource problem highlights a larger challenge of inequality, which need to be addressed both in the Maldives as well as in India. Disparities exist in terms of affordability, availability and quality of services. There is an urban rural divide when it comes to energy security in both countries as also a strong urban bias. In the Maldives, it is often the case that there is a lack of trained staff on rural islands, who often end up moving to work on island resorts for better pay. Simply switching to new technologies without local operators who are equipped to operate and maintain these new systems is futile. In this regard, training of technical personnel has to take place at all levels of the energy sector, especially at the atoll level. Inequality in energy services further affects the outer islands and invariably the growth of small and medium enterprises that are being regarded the new drivers of growth in the years to come as Maldives recovers from the loss to its tourism sector due to the pandemic months.

The approach to energy security has to be an integrated one, synergising energy challenges with poverty, inequality, rural and youth unemployment infrastructure and disaster management issues.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source: US Energy Information Agency (Based on 2016 Data)

Source: US Energy Information Agency (Based on 2016 Data) Source: The Maldives, Ministry of Energy

Source: The Maldives, Ministry of Energy  Source: The Maldives, Ministry of Energy

Source: The Maldives, Ministry of Energy PREV

PREV