India, along with the world, is entering into the last year of the decade 2011-20. During this decade, a string of programmes and schemes were launched and implemented in urban India. Whereas the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) that had been rolled out earlier, entered its closing phase, six new missions were launched by Government of India. These were the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT); Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY) - Housing for all (Urban), Smart Cities Mission (SCM), Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM), Heritage City Development and Augmentation Yojana (HRIDAY) and Deen Dayal Antyodaya Yojana – National Urban Livelihoods Mission (DAY-NULM). These were complemented by schemes to improve urban mobility. As a cluster, the missions aimed at improving the quality of life in urban areas and enhancing the delivery of urban services.

Towards the end of the decade, Government of India also came out with the National Urban Policy Framework 2018 (NUPF) that outlined “an integrated and coherent approach towards the future of urban planning in India”. The NUPF was structured along two lines. Firstly, at the NUPF’s core lay ten sutras or philosophical principles. Secondly, the ten sutras were applied to ten functional areas of urban space and management. The NUPF recognized that urban development is a state subject. Hence, the states were encouraged to develop their own state urban policies including implementation plans based on this national framework. Government of India assured its support in the development of such state policies. In the light of Government of India’s urban efforts, it could be confidently stated that GoI had very discernibly reinforced its engagement with cities during the past decade.

For the decade ahead, the year 2021 marks a significant milestone. The country will witness the conduct of a fresh all-India decennial Census that will bring forth a bevy of fresh data. A pre-test of Census 2021 has already been completed between 12 August to 30 September 2019 in all states and union territories. “The Census is not merely an exercise in head count but the compilation of invaluable socio-economic data which forms the basis for informed policy formulation and allocation of resources. The changing demographics and socio-economic parameters reflected by the Census helps in reformulation of the country’s plans for the socio-economic parameters and welfare schemes for its people”, remarked the Union Home Secretary.

While the release of the complete set of census data has taken several years in past exercises, it is expected that this time, the use of modern technology would enable compilation and release of collected facts and figures very quickly. Information gleaned from that Census should shape the policies that Government of India would formulate for the next ten years. The year 2020, therefore is, in a sense, a twilight year that allows a lookback at what governments did in the last decade. It also affords an opportunity to set its sights on correctives rather than indulge in the feverish launch of fresh programmes and schemes. Those could do well to wait for the results of Census 2021.

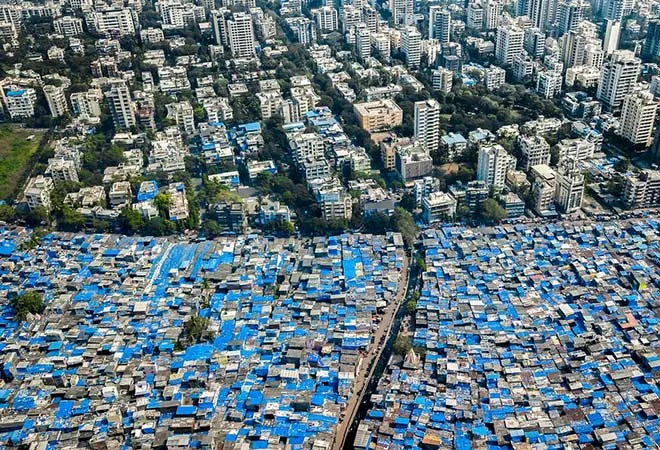

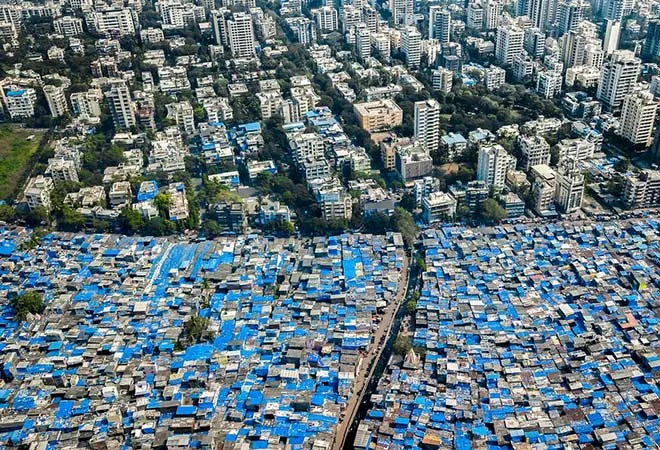

In the meanwhile, when we look back at India’s past urbanisation and the urban local body (ULB) response to the challenges, it would be obvious that for several decades now, trends of larger urbanisation are forcing ULBs to accommodate and serve more people within their geographical boundaries. An obvious corollary of this compulsion is that cities are forced to create new assets. They must build more roads, increase water supply and sewerage services, install more street lights and arrange for more waste collection. Almost all of these require additional asset creation. In addition, many cities, especially the larger ones, have been drawn into implementing Government of India-sponsored schemes. In the local arrangement of things, these schemes have taken priority, since cities are judged in their performance on the basis of how efficiently they have implemented the GoI-driven mandate.

A different set of tasks on the ground, however, also begs attention. Assets already created have to be maintained. In case they have outlived their lives, they need to be replaced. This means resources available with the cities need to be divided towards both tasks of asset building and asset maintenance/replacement. Given a choice, cities need to look for asset creation only after they have adequately provided for maintenance of existing assets. New asset creation, in a way, is an addition to future liability since these new assets, once built, get added to items of maintenance. If you cannot maintain what you have, it is clearly unwise to add to the total bag of liabilities. One, however, needs to appreciate that sometimes these finer distinctions get blurred, when pressures mount for servicing populations that are deprived of municipal infrastructure and public amenities.

Unfortunately, a general municipal trend is that there is greater emphasis on creating new assets than devoting time, money and care on maintenance. Central and state governments have further egged them on to this path. Political parties would like to make a fresh contribution to the city that would leave a very positive impression on the voters. This could then translate into their re-election. Many municipal chief executives are driven by a similar psychological compulsion of rubbishing the job done by predecessors and look to obliterate the past with their own original contribution. These human frailties put a heavy emphasis on asset creation to the neglect of maintenance.

This becomes evident when old bridges collapse; buildings fall or catch fire; roads get riddled with potholes; water and sewer lines give way and non-maintenance of storm water drains and nullahs lead to floods. These are regular occurrences in cities across India. These infrastructure failures would not have happened if the general principles of maintenance had been observed.

Municipal infrastructures include water treatment facilities, sewer lines, roads, utility grids, bridges and a large number of urban amenities. Typically, a long-life-cycle asset requires multiple intervention points including a combination of repair and maintenance activities and even overall rehabilitation. Costs decrease with planned maintenance rather than unplanned maintenance. It is important, therefore, that every city follows the essential processes and activities for infrastructure asset management. The very first of these steps is the maintenance of a systematic record of all assets (an inventory)—e.g., acquisition cost, service life and a record of past repair and maintenance. Secondly, the ULB must periodically assess the condition of its existing assets and services. Thirdly, it should develop a defined program for keeping the body of assets in running condition through planned maintenance and replace them after they have outlived their utility. Finally, it must implement and manage information systems in support of these systems.

City maintenance management systems in the developed world are increasingly using geographical information systems (GIS) to look after their assets. GIS helps store, manage, analyze, manipulate and display data that are linked spatially and thereby create a smart map. The ability of GIS is continuously improving with newer technologies and progressively becoming cheaper. A concerted effort ought to be made to get these systems into cities and train ULB functionaries in operating them.

An analysis of any municipal budget speech would reveal that municipal maintenance is a neglected subject. This needs to change. Since urban agendas today are led by national formulations, here is a suggestion – use 2020 to enunciate a national policy on the modernisation and implementation of an urban infrastructure maintenance system.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV