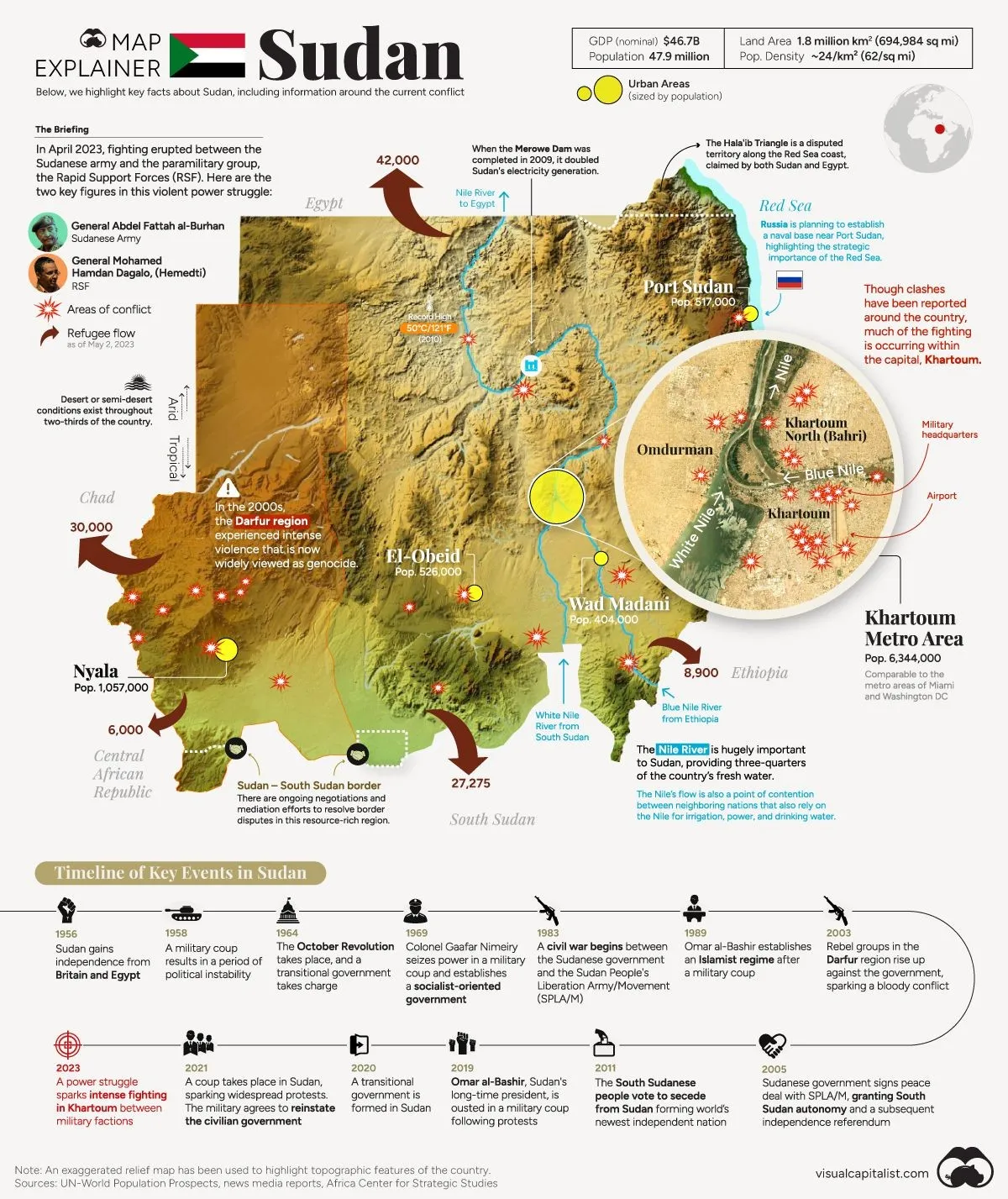

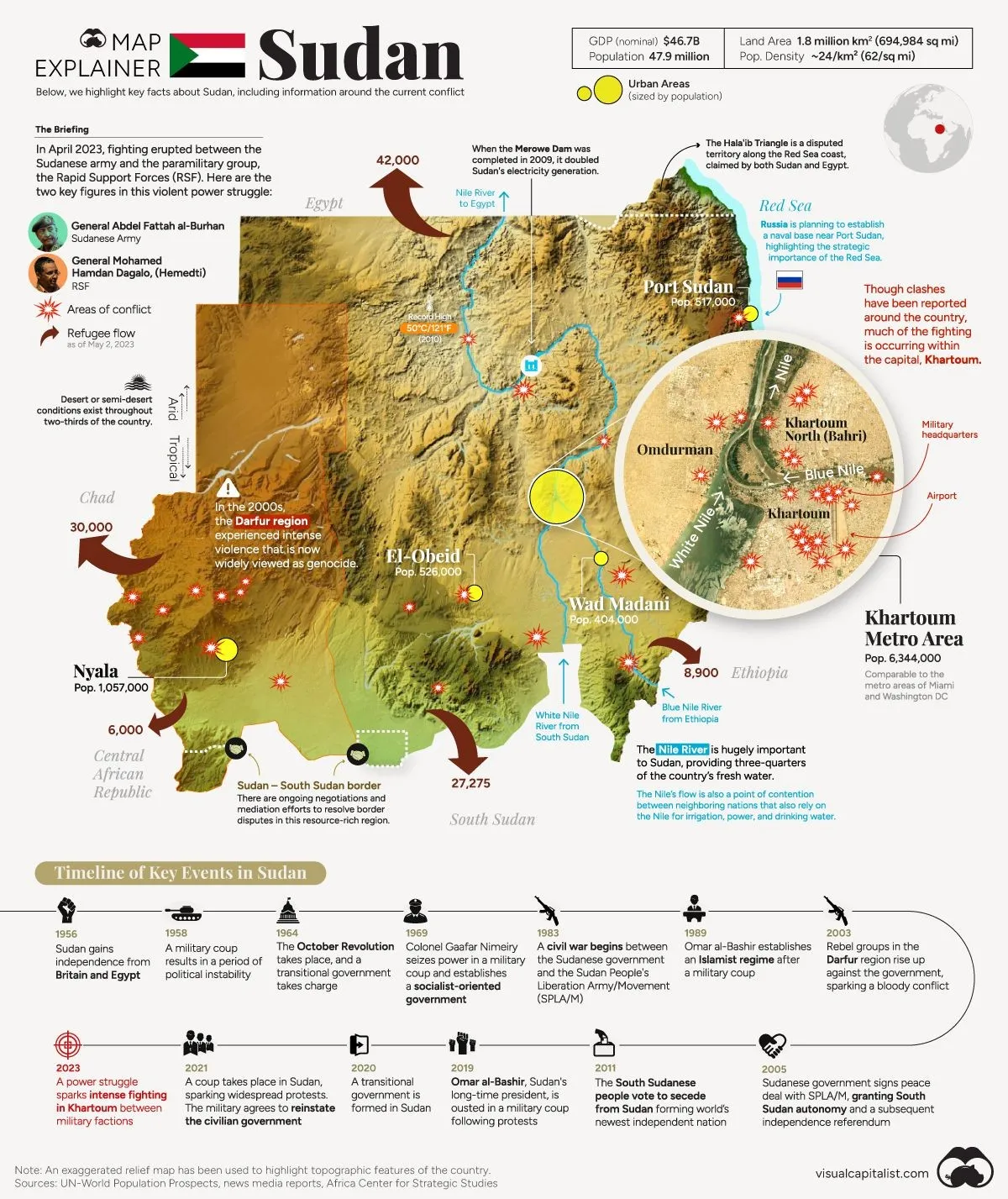

Sudan is at the precipice of a nationwide civil war as powerful rival military factions continue to battle for control of capital Khartoum. As the conflict enters its sixth week, the fallout is amply clear—

a humanitarian crisis, which has left over a thousand people dead and over a million displaced facing acute food, fuel, water, medicine, and electricity shortage.

On April 15, fighting broke out between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) following weeks of tension and disagreement over security reforms, particularly over the question of integration of the RSF into the government’s armed forces. The two protagonists in the power struggle, Army General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and his deputy and the RSF leader, General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, commonly known as Hemedti, were once allies. Together, they orchestrated a

coup in October 2021, upending a fragile transition to civilian rule that began following the massive people-power revolution, which led to the removal of former president Omar Al-Bashir in 2019.

Sudan bears geostrategic significance, which makes it too consequential for the international community to allow it to fail. The country lies at the intersection of the Arab and African worlds with a coastline of 853kms bordering the Red Sea, through which more than 10 percent of the world’s trade passes and on which Russia keenly wants a foothold. It lies at the point of confluence of the two Niles upon which Egypt depends for its water security. Sudan also has some of Africa’s largest gold mines and all its neighbouring states are all in varying states of internal strife and fragility.

The country lies at the intersection of the Arab and African worlds with a coastline of 853kms bordering the Red Sea, through which more than 10 percent of the world’s trade passes and on which Russia keenly wants a foothold.

Since its independence in 1956, the country has unfortunately endured a

kaleidoscope of civil wars and has remained a difficult place to govern characterised by decades of conflict and instability. The country has experienced six coups and 10 failed attempts at coups since independence. This could be attributed either to Sudan’s vast landscape or its wide range of ethnic, linguistic, and tribal differences among its residents.

Why are the Generals fighting?

Following the

popular revolution in April 2019, which toppled Omar al-Bashir, an uneasy alliance of generals and technocrats governed Sudan from August 2019 to October 2021, when yet another coup took place. Despite protests demanding the military and security forces hand over power to civilians, the façade of a “civilian-led transitional government” quickly ended with the arrest and removal of former Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok and his cabinet. However, despite the army’s violent repression, mass protests ensued, once again, to press for a civilian transitional government.

At the heart of the conflict lies the two generals’ insatiable desire for control of the country’s resources. For most of Sudan’s independent history, it has been ruled by an autocratic Arab elite in Khartoum, bent on reaping the benefits of the country’s wealth, mostly in the form of oil and gold. The revenues from the gold mines, which is run by the RSF—particularly in Darfur—helps fund thousands of troops under Hemedti’s command. From Hemedti’s perspective, the proposal to integrate the RSF into the army would threaten his independent economic base. His economic and

political ambitions, which hinge upon Russian and Emirati-facilitated illicit gold mining and trade, led the RSF to trespass into the SAF’s political domain.

Despite protests demanding the military and security forces hand over power to civilians, the façade of a “civilian-led transitional government” quickly ended with the arrest and removal of former Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok and his cabinet.

Hemedti continues to remain adamant and is refusing to integrate his forces—mostly comprising tribal and mercenary groups from other poor African countries—into the SAF. He is demanding a minimum period of 10 years to integrate his forces, in contrast to the SAF’s position, which is demanding two years, or the total length of transitional period, allowing the elected government to take office smoothly.

Source: Visual Capitalist, May 7, 2023

Source: Visual Capitalist, May 7, 2023

Comparing the SAF and RSF

Both the SAF and RSF’s internal organisation, equipment, combat histories, and specialisation are different. The SAF is estimated to have around 200,000 active personnel whereas the RSF is estimated to have around 70,000–150,000 personnel. Although the SAF is not highly mobile on the ground, they are a more conventional African army, which has tanks, armoured personal carriers, and an air force that gives them air superiority. The SAF sources most of its aircrafts, missiles, and armoured vehicles from China, Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. However, following the 2004 violence in Darfur, the United Nations imposed an

arms embargo, which disrupted the SAF’s weapons’ supply chains.

On the other hand, the RSF was set up as an extension and counterweight to the SAF, evolving from the

Janjaweed militias who were tasked with combatting secessionism in Darfur under the leadership of al-Bashir. Over the years, Hemedti rose through the ranks in the RSF, took over its leadership, and officially became part of the

Sudanese state security apparatus in 2015. Tactically, the RSF is like a mobile guerrilla and counterinsurgency force, which is more lightweight and uses light armoured vehicles. However, the RSF never received any military training like the SAF, which renders the task of defending positions or sustaining attacks difficult for the RSF. At this juncture of the conflict, it is amply clear that both sides are stuck in a deadlock with neither the SAF nor RSF gaining an upper hand over its rival.

The RSF was set up as an extension and counterweight to the SAF, evolving from the Janjaweed militias who were tasked with combatting secessionism in Darfur under the leadership of al-Bashir.

Inadequate regional and international response

The international community has been too slow to recognise the risks in Sudan and has done little to support its democratic transition. Both the warring generals have not shown any appetite for ceasing hostilities, with both sides showing no unequivocal sign that either is ready to seriously negotiate. The African Union (AU), on its part,

condemned the violence in Sudan and called for an immediate humanitarian ceasefire. Despite the US, Saudi Arabia and UAE brokered ceasefires, the fighting continues to rage on. Consequently, Sudan has been

suspended from membership of the AU.

Regional powers and Sudan’s neighbours have expressed their support for either of the two generals - or for both factions in some cases. Egypt, which ha a long history of meddling in Sudan’s affairs, and Saudi Arabia, have been backing the SAF and al-Burhan, whereas the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and General Khalifa Haftar of Libya have backed the RSF. Many other countries remain undecided. Sudan’s relation with Ethiopia has also strained due to border disputes over land claims in region like Al Fashaga and disagreement over the

Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). It is also important to point out that escalating tensions in Sudan’s Darfur region risks spilling over in its western front and affect countries like Libya Chad and the Central African Republic (CAR).

Sudan’s relation with Ethiopia has also strained due to border disputes over land claims in region like Al Fashaga and disagreement over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD).

Both Russia and China also have significant interests in Sudan. Russia is allegedly negotiating a military deal that would allow it to

establish naval facilities in Port Sudan in the Red Sea which hosts critical shipping lanes. Russia’s private military company – the Wagner Group’s contractors have also been regularly deployed to guard Sudanese gold mines. China also has made significant investments in Sudan over the years and a prolonged conflict threatens its economic interests. For some time now, China has been positioning itself as a

regional peace-broker, with the historic resumption of diplomatic ties between Iran and Saudi Arabia. This was preceded by China holding the sponsoring the first ever

Horn of Africa Peace, Good Governance and Development Conference in June 2022.

The distracted international community is under severe pressure to find a lasting solution to the ongoing Sudanese conflict. Countries like the United States, France, United Kingdom, and other European countries are scrambling to evacuate its diplomatic staff and safely repatriate its citizens from Sudan. The Indian Government launched its evacuation programme, termed ‘

Operation Kaveri’, on April 24 to bring back its stranded citizens. As part of the operation, India established two separate control centres in Jeddah and Port Sudan to assist in the evacuation. India safety brought back nearly 4000 citizens by using its Air Force (17 flights) and its Navy (5 sorties were made by Indian ships). India has also assisted Sudan by providing

24,000 kg of humanitarian relief supplies.

To achieve any meaningful and lasting settlement to the conflict, the two warring generals need to find an agreement over two central issues: Handing over power to civilians as long promised, and the question of integrating the RSF into the national army. Going forward, the troika of the UN, AU, and the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD), a regional bloc in the Horn of Africa, is best placed to lead any form of mediation efforts to end the Sudanese conflict.

Abhishek Mishra is an Associate Fellow at the Strategic Studies Programme, Observer Research Foundation.

Kshipra Vasudeo is a Ph.D. Research Scholar at the Centre for African Studies, School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Sudan is at the precipice of a nationwide civil war as powerful rival military factions continue to battle for control of capital Khartoum. As the conflict enters its sixth week, the fallout is amply clear—

Sudan is at the precipice of a nationwide civil war as powerful rival military factions continue to battle for control of capital Khartoum. As the conflict enters its sixth week, the fallout is amply clear—

PREV

PREV