The United Nations (UN) Climate Change Conference,

COP27, was held from 6

th to 20

th November in Egypt. It reminded the world of the looming crises, how little has been done, and how much more is needed.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) indicated in its

Sixth Assessment Report that greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions should be cut by 43 percent by 2030 as compared to the 2019 levels. This would be critical to limiting global average temperature rise to well below 2

oC and preferably to 1.5

oC above pre-industrial levels by the end of this century, which was agreed upon at COP21 in Paris. The Report also estimated that the world will likely hit this threshold by 2040, if not earlier, and in the worst-case scenario it will be 4.4

oC warmer by the end of this century. As a prelude to COP27,

The Economist warned that

“the world is going to miss the totemic 1.5oC climate target”. Of

the 40 actions required for meeting that target, none are on track. Twenty-seven are moving in the right direction but well below the required pace; five are going in the wrong direction; and the remaining eight lack sufficient data. There is a 48-percent chance of reaching the 1.5

oC target in five years or less.

The science of global warming is clear and convincing. Greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide (CO

2), methane (CH

4), nitrous oxide (N

2O) and ozone (O

3) together make up less than 0.04 percent of the Earth’s atmosphere but disproportionately affect climate by trapping the planet’s heat. This “greenhouse effect” is important, for without it the Earth’s surface temperature would be about minus 18

oC, and there would be no liquid water. Anthropogenic activity has steadily added GHGs to the Earth’s atmosphere—carbon dioxide from burning coal and other fossil fuels; methane from decaying organic material (including digestion of food by cattle); nitro oxide from agriculture, fossil fuels, and solid waste, and ozone from hydrocarbons (petroleum products, refrigerator coolants, etc.). This traps more heat and causes global warming. The

biggest fraction of GHG emissions is CO2 (74.4 percent), with CH

4 (17.3 percent), N

2O (6.2 percent) and other emissions (2.1 percent) making up the rest.

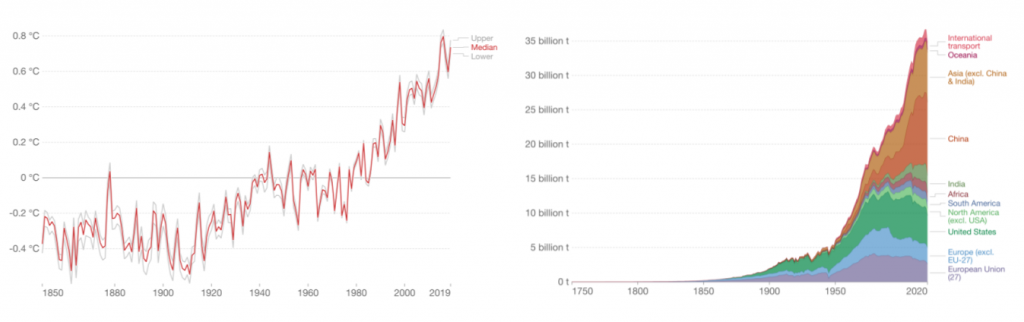

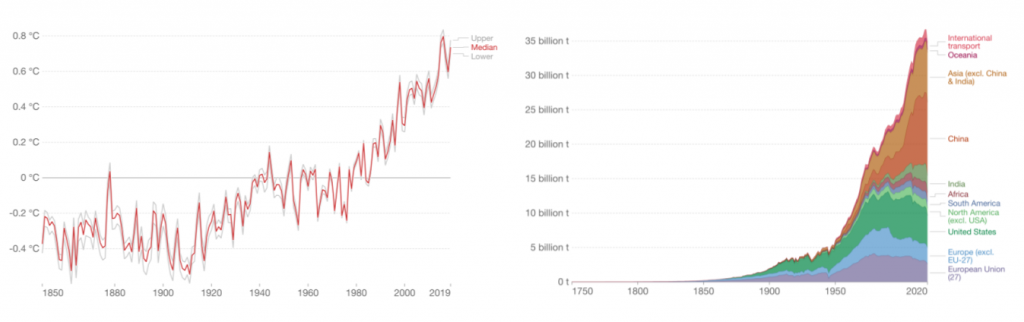

A daily record of atmospheric CO

2 is called the

Keeling Curve. It shows the global average CO

2 concentration to have increased from 313 parts per million (ppm) in 1958 to 416 ppm now. Temperature measurements, initially from weather stations on land and on ships, and from satellites and geologic records, tell the story of a warming planet. Since 1880, average global temperatures have increased by 1.2

oC, most of it in the late 20

th century. Land areas have warmed more than the oceans, with average temperatures in the Arctic increasing by over 2.2

oC since just the 1960s. The Earth is warmer today than any other time in the past millenium. This is reflected in increasing average temperatures and correlates with the rising global CO

2 emissions (Figure 1).

Figure 1. (Left) Rise in global mean temperatures from 1850 to 2019, using the 1850 to 1900 period as a pre-industrial baseline. The 0.8oC rise now is equivalent to about 1.2°C above pre-industrial levels. (Right) Annual global CO2 emissions, with contributions from different regions of the world.

Figure 1. (Left) Rise in global mean temperatures from 1850 to 2019, using the 1850 to 1900 period as a pre-industrial baseline. The 0.8oC rise now is equivalent to about 1.2°C above pre-industrial levels. (Right) Annual global CO2 emissions, with contributions from different regions of the world.

Since July 2020, the

Climate TRACE initiative has mapped and tracked specific sources of GHG pollution across countries and two dozen sectors of the global economy. It uses artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms to combine data from over 300 satellites and 11,000 sensors to identify all of the largest point sources, track them over time, and to make the data publicly available. During COP27, Climate TRACE released the

largest global inventory that covered 70,000 of the highest GHG emissions sources. It showed oil and gas production fields and their associated facilities to be the biggest emitters, with emissions being underreported by up to three times. Over the next 20 years, there would be

80.7 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent emissions globally, of which fossil fuels operations (24.21 percent), power (18.49 percent), agriculture (17.01 percent) and manufacturing (12.55 percent), would be the biggest sectoral emitters. During the same time frame,

India may emit 5.62 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent, of which agriculture (31.09 percent), power (22.28 percent), manufacturing (13.86 percent) and waste (11.49 percent), would be the biggest sectoral emitters. Fossil fuel operations (8.32 percent), transportation (5.45 percent), and buildings (5.37 percent) are likely to be the other significant sectoral emitters for India.

In 2022, extreme weather events brought widespread destruction, claimed hundreds of thousands of lives, and displaced millions of people worldwide.

Global warming is not just higher temperatures, but also erratic weather patterns, droughts, floods, and rising sea levels that will adversely impact life on Earth. In 2022,

extreme weather events brought widespread destruction, claimed hundreds of thousands of lives, and displaced millions of people worldwide. South Asia was the epicentre of heatwaves, erratic rains caused widespread flooding across Pakistan, Northeast India, Bangladesh, and China faced its worst drought in over 60 years. Europe, experienced the hottest month of May ever, and nearly half of the continent faced its worst drought in over 500 years. Higher than usual temperatures in the Arctic led to record ice melts. According to the New Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment, India witnessed 242 days of extreme weather somewhere in the country during the first nine months of this year. The five states of Assam, Himachal Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Uttar Pradesh reported more than 100 days of extreme weather events during this period. This is estimated to have caused over 2,700 deaths and damaged 1.9 million hectares (or ~1 percent) of crops in India.

According to the United States

National Intelligence Estimate on Climate Change, reduced food security and the emergence of new diseases will lead to large-scale migration, climate refugees, political instability, and increased global security risks. There would be increasing geopolitical tensions on ways to reduce GHG emissions, cross-border flashpoints, and potential for instability and internal conflicts in developing countries that did little to create the problem, but will feel the biggest impact of climate change. India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan were among the 11 countries singled out as being “highly vulnerable” in preparing and responding to the climate crisis.

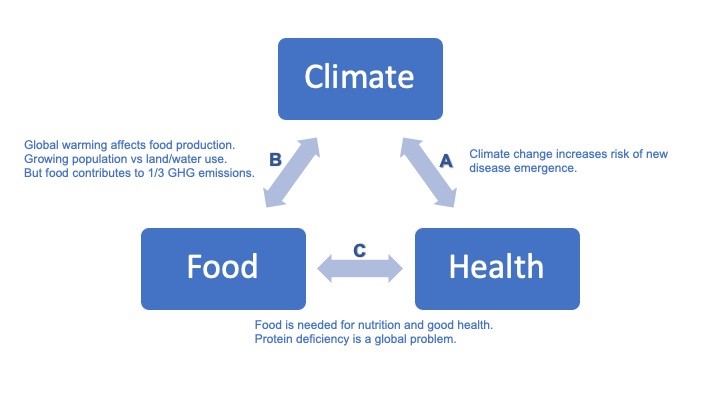

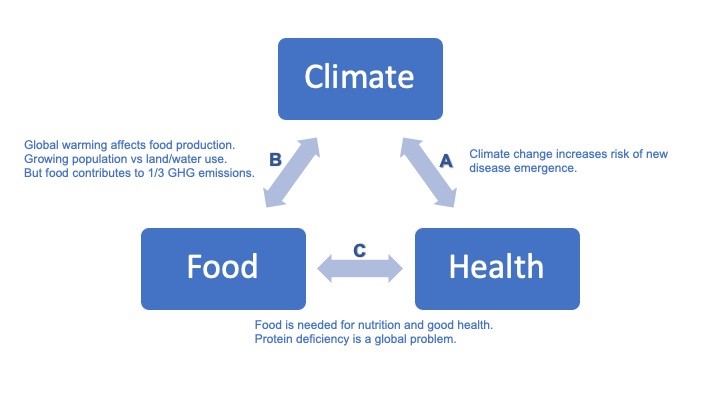

Figure 2. The troika of climate change, health and food systems. (A) Climate change directly affects physical and mental health of people through high temperatures, flooding, and spread of infectious diseases. (B) Global warming affects food production at a time when an increasing population needs more food and water. But food production, processing and consumption also contribute to GHG emissions that drive global warming. (C) Food is required for nutrition and good health, but processed foods drive chronic “lifestyle” diseases and there is widespread protein deficiency, which needs climate-friendly alternatives.

Figure 2. The troika of climate change, health and food systems. (A) Climate change directly affects physical and mental health of people through high temperatures, flooding, and spread of infectious diseases. (B) Global warming affects food production at a time when an increasing population needs more food and water. But food production, processing and consumption also contribute to GHG emissions that drive global warming. (C) Food is required for nutrition and good health, but processed foods drive chronic “lifestyle” diseases and there is widespread protein deficiency, which needs climate-friendly alternatives.

Climate change affects the health of humans and animals as well as food systems. The effects, however, are not unidirectional (Figure 2). While each is a significant challenge, their interdependence increases the difficulty in developing policies without unpopular trade-offs. India’s geography, high population density, dependence on the weather for food sufficiency, and poor healthcare infrastructure place the country at a high risk.

Read Part II of the series that explores the link between climate change and health.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

The United Nations (UN) Climate Change Conference,

The United Nations (UN) Climate Change Conference,

PREV

PREV