This brief is a part of

The Ukraine Crisis: Cause and Course of the Conflict.

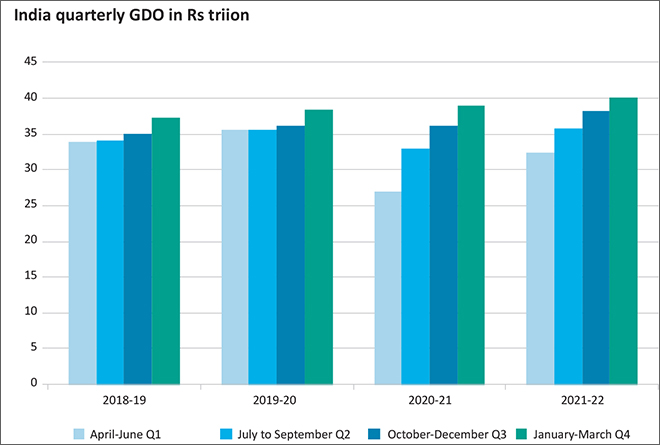

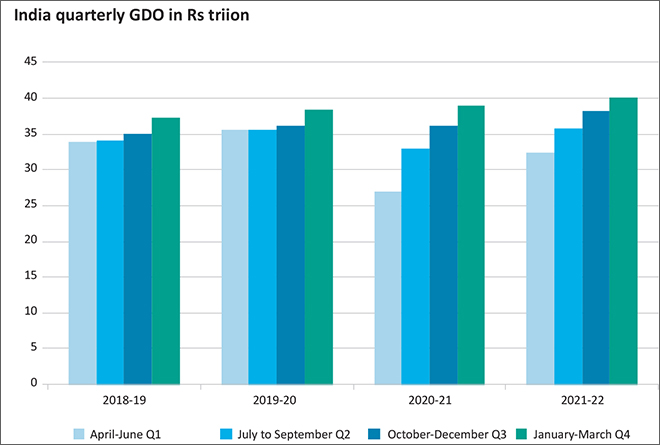

There is a great deal of unnecessary melancholy around the low real growth outturns for the October to December quarter (Q3) FY 2021-22. The gripe, if any, is that Q3 confirms a downward trend in quarter-on-quarter growth rates, down from 20.1 percent in Q1, 8.4 percent in Q2, and now 5.4 percent in Q3.

It is possible that growth in the current quarter (Q4—January to March 2022)could slip even lower to between 4 to 4.5 percent with annual real GDP growth averaging 8 to 8.5 percent in 2021-22, instead of the 8.95 percent projected by the National Statistical Office (NSO) on 28 February 2022.

Two quarters of low but positive growth followed, inducing the then Chief Economic Advisor to prematurely, declare a V shaped recovery was underway, with a bit of econometric license.

How calamitous would this be? It is a reduction of around INR 1.2 trillion in the NSO estimate of real GDP of INR 147.72 trillion for 2021-22. Compare this with INR 10.11 trillion India lost in the previous fiscal 2020-21 (computing GDP loss versus the 2019-20 GDP of 147.9 trillion—the last year prior to the pandemic). The emotional quotient of impatience with “slow growth” this fiscal, overshadows the statistical relevance of the shortfall.

The table below illustrates that India suffered a dramatic fall of over 24 percent in real GDP in Q1 2020-21) induced by the pandemic dislocations, followed by an immediate correction in the next quarter with the quarter-on-quarter loss in GDP reducing to 7 percent. Two quarters of low but positive growth followed, inducing the then Chief Economic Advisor to prematurely, declare a V shaped recovery was underway, with a bit of econometric license.

The current fiscal 2021-22 opened with GDP levels in Q1 higher than the previous year but still 9.2% below the “normative” level in Q1 2019-20. The positive trend versus 2019-20 has continued, albeit with slowing growth levels. By the end of this fiscal, we will be back to where we were at the end of fiscal 2019-20. The real problem is a perception of stagnation, which is partly driven by the abnormally high expectations aroused around India’s “fast growing” economy.

As we side into a new fiscal 2022-23, we are likely to grapple with the reality that the tagline of a “fast growing” economy still has to be earned. To be sure the potential exists for 8 plus percent annual growth. How it can be quickly realised is the trillion-rupee question.

The fiscal consequences of slow growth

One of the downsides of slow growth is the consequential fiscal squeeze, hampering public investment-led recovery and enhanced income support for the jobless. In the first 10 months of the current fiscal (April 2021 to January 2022) revenue receipts and non-debt capital receipts grew by 16 percent—a healthy recovery—but lagging growth in the full year’s nominal GDP, forecasted by NSO at 19 percent.

The real problem is a perception of stagnation, which is partly driven by the abnormally high expectations aroused around India’s “fast growing” economy.

The burden of interest payments increased this fiscal by 19.7 percent over the previous fiscal, albeit with budgeted moderation in the next fiscal (FY 2023) to 15.6 percent. If the Ukraine crisis blows over, global interest rates will likely harden and the budgeted moderation in the interest burden could erode. Conversely, if the Ukraine crisis persists, and global shocks negatively impact growth and jobs, the US Federal Reserve could defer normalisation of interest rates, which would be to India’s advantage, as we are further away from normalisation than the US. Perversely, we stand to gain from Ukraine’s misery.

Ukraine fast forwards geopolitical discord

The unfolding Ukraine crisis has added to global uncertainty and disruption emerging from the pandemic. However, it is also an opportunity.

The crisis was perpetuated by indifference to long-standing Russian security concerns of NATO operational creep. President Putin’s determination to assert the centrality of his strong leadership to “Imperial” Russia was underestimated, in a year when President Xi is slated to cement his position in “Imperial” China.

Ukraine’s democratically elected President opted for the high-risk, albeit courageous, strategy of risking a crippling war waged on home ground. Compare this with the pragmatic and nuanced holding strategy that India adopted to defuse the 2020 border conflict with China, recognising the near-term asymmetries between the two countries and the domestic, political compulsions driving China’s aggressive posture.

An “honorable truce” in Ukraine suits all actors. It mollifies President Putin. It allows wealthy and ageing western Europe to return to socially conscious, conspicuous consumption, early pensions, comfortable work-life balance, and nanny state benefits with low ratios of military expenditures to GDP—even less than lower middle-income India.

The structural frailties of the Indian economy—inefficient allocation of public and private capital, low levels of competitiveness in the critical financial and infrastructure sectors, low governance standards in the delivery of public services and faltering human development strategies—evident since 2017, need significant reform effort.

It suits President Xi too. Russia’s intemperate military response at not being taken seriously and now the near deafening pusillanimity in forging a forceful counter-response (shades of the Rwanda genocide 1994) loudly signals the hollowness of NATO’s claims of mutually beneficial deterrence, whilst red-lining the jaded appetite of the United States to suffer the costs—fiscal and human—of global leadership. The Ukraine crisis also reinforces the inevitability of Taiwan having to seek, cap in hand, an eventual rapprochement with “Imperial” China.

China and India have already signaled their accommodation of Russian security concerns by not supporting the US-promoted UNSC resolution to censor Russia. However, continuing to turn a Nelson’s eye to a potential massacre in Ukraine, risks inviting negative consequences for Chinese and Indian business and trade relationships in Europe and elsewhere. Like NATO, China and India have an interest in defusing the crisis.

For India, the Ukraine crisis comes at an inopportune time when it must focus on stoking growth domestically. The structural frailties of the Indian economy—inefficient allocation of public and private capital, low levels of competitiveness in the critical financial and infrastructure sectors, low governance standards in the delivery of public services and faltering human development strategies—evident since 2017, need significant reform effort.

Ukraine presents an opportunity for global economic leadership

India does not shy away from upholding the spirit of common global commitments. Prime Minister Modi generously supported the World Health Organisation sponsored, global, COVID-19 vaccine supply programme to low-income countries (COVAX) in 2020. At COP26 in Glasgow, 2021, he committed India—a country with less than one half of the per capita global carbon dioxide emissions—to work towards becoming Net Zero in 2070.

India could now demonstrate its commitment to growth sustaining global action by proposing a UN-sponsored initiative to stabilise global grain and oil prices. The sanctions constrained Ukrainian and Russian supplies of these essentials are already generating a global price shock.

India could now demonstrate its commitment to growth sustaining global action by proposing a UN-sponsored initiative to stabilise global grain and oil prices.

India has elevated buffer stocks of food grains, wheat (28 million tons) and rice (26 million tons) in the central pool, which it can offer for sale at globally regulated prices. The United States and other OECD countries have substantial strategic oil reserves which could be used similarly to moderate the price of oil, which topped US$111 per barrel (Brent). This “food & fuel” global price stability initiative could protect the poorest countries from suffering a price shock in essential goods.

Managing domestic inflation

Domestically, India has a tax cushion to dampen imported inflation via counter cyclical fiscal policy rather than use monetary policy for the purpose. With growth still incipient, a precautionary firming up of interest rates could compromise growth prospects. Reducing the high tax levied on the retail sale of fuel can neutralise the inflationary impact of passing through elevated prices of imported oil, without depleting the balance sheets of the publicly-owned oil companies, who have absorbed the increase thus far. Halving the amount of tax imposed by the Union government can reduce inflation by 0.6 percent or 60 basis points (one percent equals 100 basis points). This could reduce consumer price inflation significantly below the 6.1 percent in January 2022, helping to bring it closer to the rate of 4.9 percent assessed by the monetary policy committee of the Reserve Bank of India for April to June (Q1) 2022-23.

Reducing the high tax levied on the retail sale of fuel can neutralise the inflationary impact of passing through elevated prices of imported oil, without depleting the balance sheets of the publicly-owned oil companies, who have absorbed the increase thus far.

Evolving a political consensus within India on a carefully crafted domestic agenda will be critical for traversing the risks imposed by an uncertain global environment. The task goes well beyond undertaking big infrastructure programmes, which have been the standard antidote to counter economic slowdown. Targeting a more competitive economy is now critical to shake-off the grudging acceptance of growth pessimism.

A fractured global economy breeds big government

The sanctions imposed by the United States on Russia over its aggression in Ukraine and the support extended by Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, the European Union, and Japan define a fracturing of the global economy with potentially damaging consequences for trade and growth. Couple this with the heightened geopolitical contestation, as opposed to collaboration, and the options for global openness are narrowing. An open economy generic stance is now passé, replaced by targeted sovereign choices for partnerships—a role that even well-endowed governments find difficult to execute efficiently.

Is it time then to navel gaze? Review, at arms-length, strategic alliances to recognise the centrality of preserving a nurturing ecosystem within the Indo-Pacific region, as the Petri dish for India, China, and other regional actors to attain their economic potential.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This brief is a part of

This brief is a part of

PREV

PREV