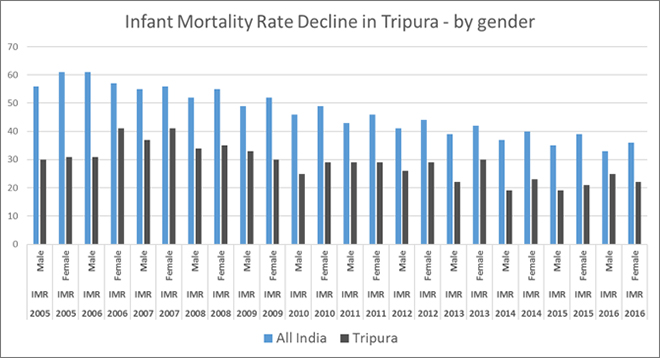

Despite being one of the poorest states of India, with Dalits and Adivasis constituting half of its population, Tripura has had some remarkable successes in health and determinants to health. Tripura’s proportion of households with an improved drinking-water source (87.3%) as well as using improved sanitation facility (61.3%) increased by 10 percentage points over the last decade. A remarkable 92.7% households of the state have access to electricity. Women’s literacy rate is higher than the India average. Despite lack of rapid economic development, Tripura achieved fertility rates below the replacement levels in the nineties itself, along with a handful of other Indian states like Goa, Tamil Nadu and Kerala — far ahead to it in terms of economic development. As recently as in 2005, Tripura had a lower Infant Mortality Rate (31) than Tamil Nadu (37) or Delhi (35), states which were much higher up on the economic development ladder.

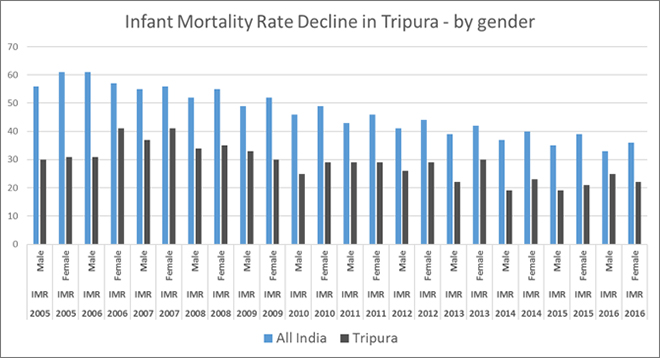

However, over the last decade, the rate of improvement in infant mortality has been uneven as the following graph shows. According to the latest IMR figures available for the year 2016, both Tamil Nadu (17) and Delhi (18) have already overtaken Tripura (24). Urban IMR has been a particular concern for Tripura, and latest data indicates that currently only three states in India — Uttar Pradesh (34), Madhya Pradesh (33) and Odisha (34) — have a higher urban IMR than Tripura (32).

Source: SRS Bulletin, various years

Source: SRS Bulletin, various years

Staff shortages in health sector

Historically, Tripura has followed a public-sector centric approach to healthcare provisioning, with a focus on primary level care. Between 1985 and 2016, Tripura increased the number of the sub centres from 230 to 1,033. Number of PHCs were increased by three times, and number of CHCs increased by six times in the same period. Latest data available shows that there is no PHC in Tripura which has no physician. Availability of nursing staff in PHCs and CHCs remain sufficient as well. According to the National Sample Survey 71st Round data, more than 90% people of Tripura still depend on public sector for hospitalisation care.

However, a closer look at latest data on specialist care at the CHC level consisting of surgeons, physicians, paediatricians, obstetricians and gynaecologists, Tripura has huge gaps which calls into question the quality of care delivered through the public sector. Out of 80 specialist doctors needed in Tripura’s CHCs, only one was in position. Based on 2011 population numbers, while there are sufficient number of sub centres, there are considerable shortfalls in the number of PHCs and CHCs needed in the state — 14% and 26% respectively. Being a poor state with very high rates of unemployment, is their lack of purchasing power pushing people into crowded public facilities offering secondary and tertiary care, reeling under severe staff shortages? Currently, Tripura has the highest rates of unemployment in India, with unemployment four times the national average.

Tripura has the highest rates of unemployment in India, with unemployment four times the national average.

High absenteeism of public sector staff may be another issue compounding the burden of staff shortages. Through a sting operation conducted in January 2018, a media house reported that in key departments of two of Tripura’s tertiary hospitals, no doctors were available during the day, despite long queues of patients.

Tripura’s performance in last decade

Tripura has one of the lowest average total medical expenditure for treatment per hospitalisation case among Indian states. This is to be expected, as more than 90% of the population depends on the public sector for hospitalisation care. Surprisingly, data from 2014 shows that average total medical expenditure per childbirth in public hospitals at ₹4,312 (rural) and ₹5,209 (urban) was among the highest within Indian states. The national average was ₹1,587 (rural) and ₹2,117 (urban).

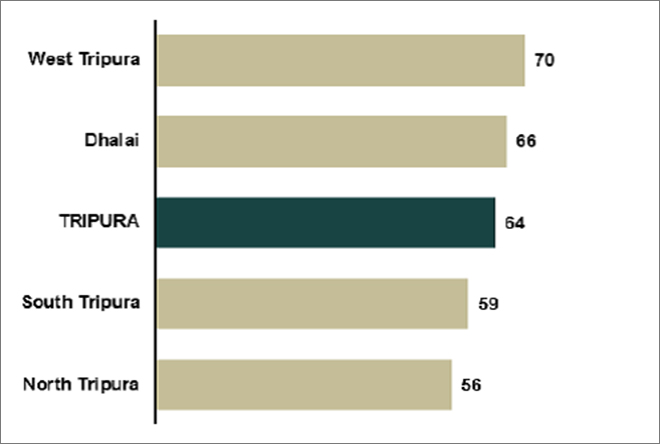

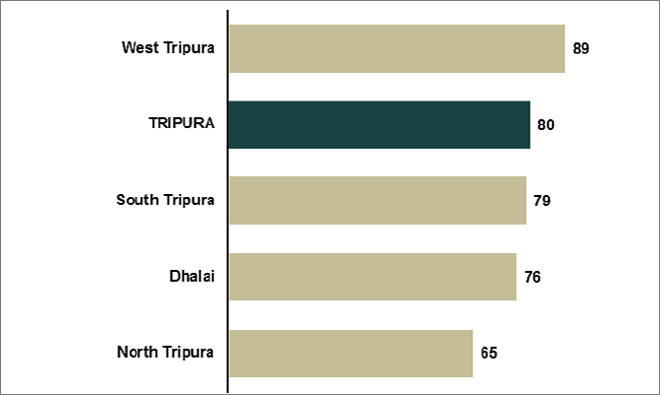

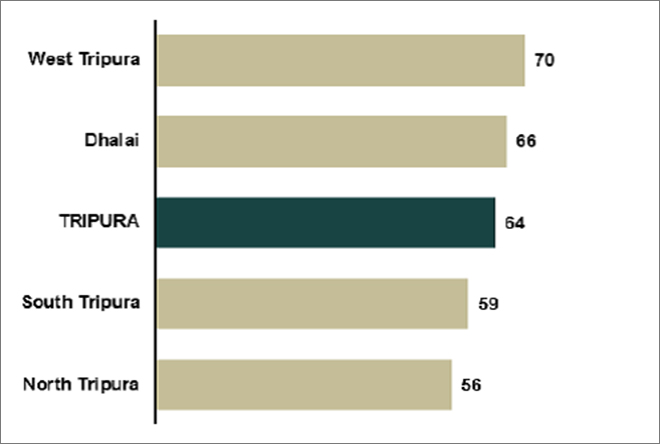

According to data from NFHS-4, almost two-thirds Tripura’s mothers had four or more antenatal care visits; urban women were more likely to receive four or more antenatal visits than rural women. The proportion a decade ago was 50.6%, which shows some improvement. However, as the following Graph shows, there are considerable inter-district differences (this article follows the former administrative structure, as NFHS data is still arranged across the old set of 4 districts).

Percentage of mothers who had at least 4 antenatal care visits

Source: NFHS

Source: NFHS

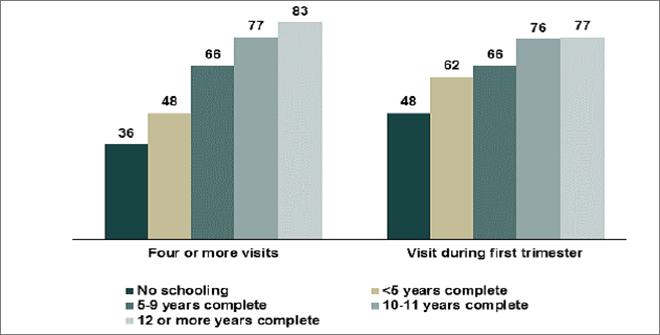

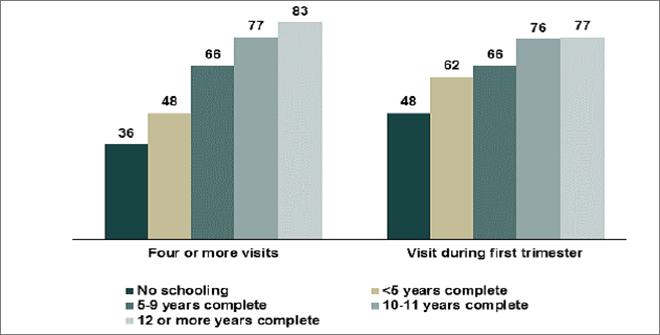

Access to antenatal care is seen to be influenced by the level of mother’s schooling as the next Graph shows. Women with more years of schooling were much more likely to have antenatal care access than women with no schooling.

Access to antenatal care across educational categories

Source: NFHS

Source: NFHS

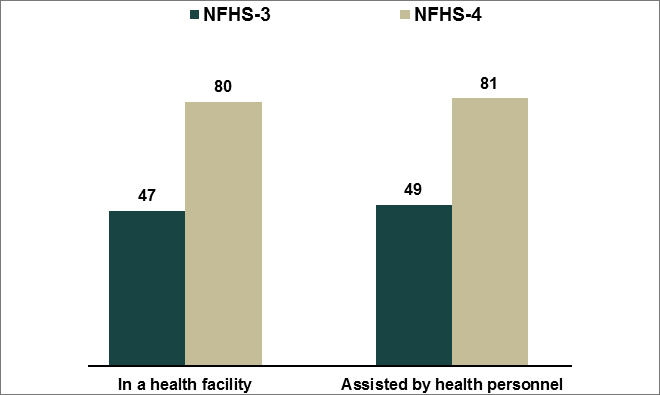

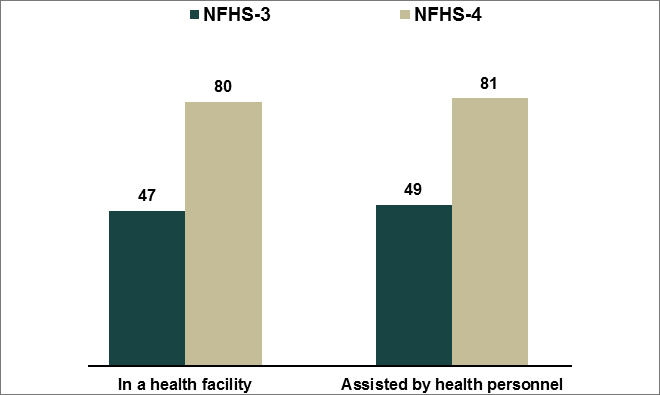

According to the NFHS 4 State Report, about four-fifths of births (80%) in Tripura take place in a health facility (mostly a government facility) and 20% take place at home. The proportion institutional deliveries increased remarkably in the last decade, from 47% in 2005 to 80% in 2015 (graph). The chances of having an institutional birth was seen to improve for women who have received an antenatal check, women in urban areas, women with 12 or more years of schooling, women who are having their first birth, women from a Dalit or OBC categories, and Hindu women.

Status of institutional deliveries in Tripura

Source: NFHS

Source: NFHS

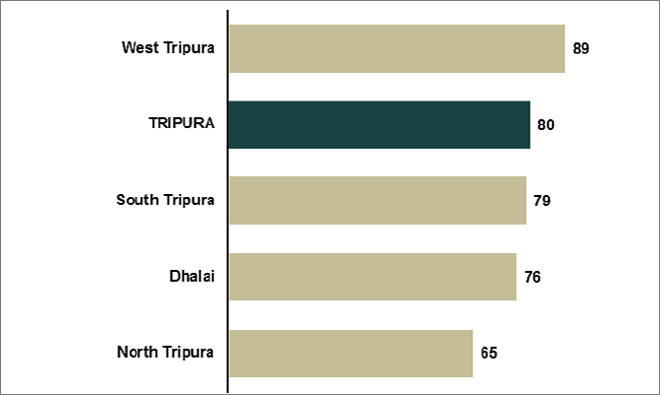

It is seen that only 33% of mothers who had an institutional delivery received financial assistance under the Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY). According to the NFHS 4 State Report, rural women were more likely than urban women to receive financial assistance under JSY, as were women with less than 10 years of schooling. Scheduled tribe women were more likely than any other caste/tribe group of women to receive financial assistance under JSY, showing it was reaching the intended beneficiaries. However, efficiency in targeting is rendered ineffective by the low level of coverage. In addition, there are stark inter-district differences within institutional deliveries as well as the next graph from the state NFHS report shows. There is a difference of 24 percentage points between West Tripura district and North Tripura.

Institutional deliveries in Tripura — district-wise

Source: NFHS

Source: NFHS

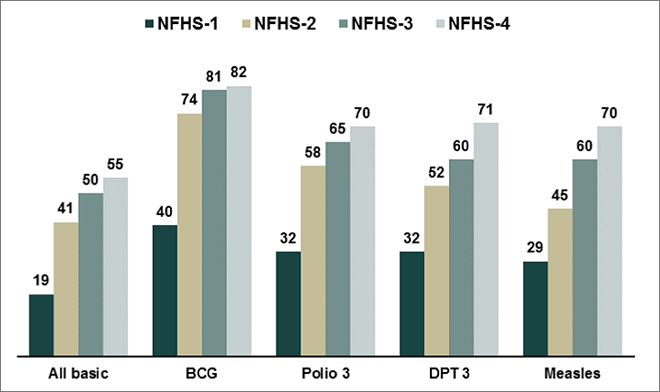

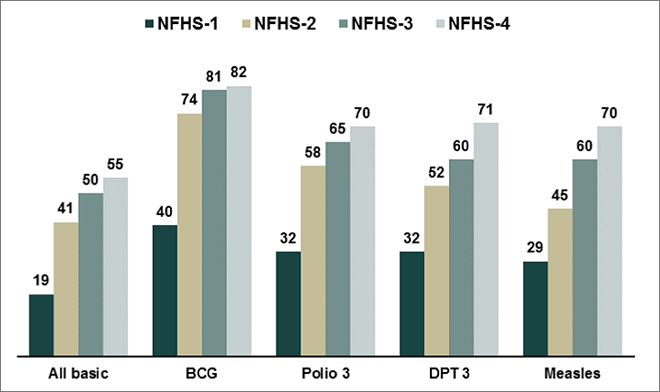

In 2005, Tripura’s coverage of full immunisation was better (49.7%.) than the national average (43.5%). Over the last decade, the India average (62% in 2015) has overtaken Tripura (54.5% in 2015) and the low levels of vaccination coverage is a major cause for worry for the state. While there is improvement (graph), the fact that only half of the state’s children receive full immunisation points to the possibility of epidemics which can put extra pressure on the meagre health resources of the state. Among the four districts, Dhalai has a further low level of coverage (44%), which needs immediate attention.

Vaccination coverage in Tripura over the years

Source: NFHS

Source: NFHS

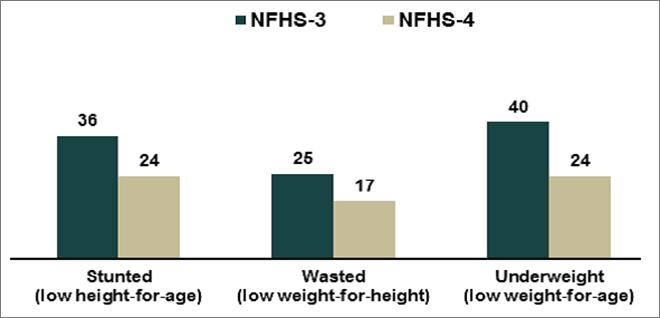

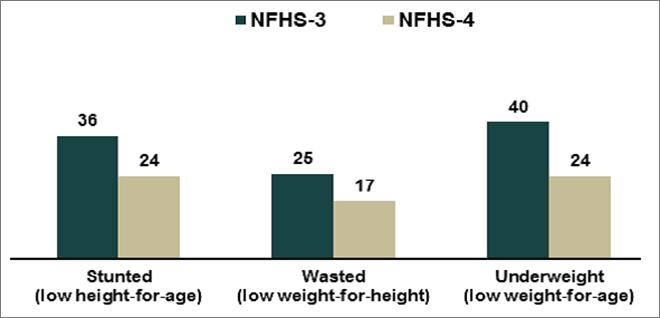

Child nutrition is an area where Tripura has made remarkable progress. Over the last decade, Tripura was able to bring down stunting, wasting and underweight levels considerably (graph). According to the NFHS 4 State Report, there are only small differences in the level of undernutrition by gender or by the child’s living arrangements. Undernutrition decreases with increasing mother’s schooling, better nutritional status of the mother, and larger child’s size at birth. While overall levels are falling, the level of undernutrition is relatively high for children of higher birth orders and from Muslim families in Tripura.

Tripura’s success in the battle against under-nutrition

Source: NFHS

Source: NFHS

Experience with rapid expansion of insurance coverage

Given the emerging weaknesses of its public sector health infrastructure, Tripura has also been a pioneer in broad-based, government-financed health insurance schemes, taking coverage beyond the BPL population. In 2014, the state launched Tripura Health Assurance Scheme for Poor (THASP) engaging major public and private sector hospitals providing specialist care across the country.

The scheme supports expenses to the extent of ₹1.25 lakh per annum for treatment of 36 major diseases across seven broader categories — cancer, neurosurgeries, kidney-related diseases, cardiovascular surgeries, neo-natal diseases, poly-trauma and ophthalmic disorder. Latest government data available shows that between 2005 and 2015, while the proportion of Indian households covered by a health scheme or health insurance went up from 4.8% to 28.7% , which in itself is remarkable, in Tripura the coverage shot up from 0.9% to 58.1%. Tripura achieved this by offering THASP to 7.85 lakh of the total 8.55 lakh families of the state.

Evaluations of the THASP experience can offer insights to inform the formulation and implementation of NHPS, India’s proposed vehicle to Universal Health Coverage. In the meantime, the state needs to put considerable efforts to improve its public health infrastructure and services on which a majority of its people depend. The coming assembly elections offer the state an opportunity to discuss and debate future plans to accelerate the health and nutrition improvements of the state, while taking care of existing bottlenecks.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source:

Source:  Source:

Source:  Source:

Source:  Source:

Source:  Source:

Source:  Source:

Source:  Source:

Source:  PREV

PREV