The China Way

The COVID-19 pandemic is undoubtedly hurting the global economy in a multitude of ways. Not only have the intermittent lockdowns and other restrictions interrupted market forces from approaching equilibrium, but they have also led to devastating supply chain disruptions and resource crunches across sectors. With the onset of the pandemic, the over-dependency on Chinese manufacturing had started to hurt global economic growth. During the SARS outbreak in 2003, China only contributed to about 4 percent of global output, which had increased to a whopping 16 percent in 2020. With the SARS-CoV-2 virus originating in China, the subsequent allegations against the country over its handling of the crisis, and the ongoing US-China trade war, foreign investors in China have already began shifting their manufacturing activities to countries like India, Bangladesh, Thailand, Vietnam, and Philippines.

The health emergency caused by the pandemic has dampened the BRI ambitions to a large extent even though Beijing is still determined to go ahead with it.

Against this background, it is noteworthy to put the spotlight on China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Conceived in 2013 by the Chinese Government, the One Belt One Road (OBOR) project (former name for BRI) stood out as one of the crucial tenets of Xi Jinping’s foreign policy, which aimed to enhance physical infrastructure for development cooperation across several countries in Asia, Europe, Africa, and even Latin America. Even prior to the pandemic, the BRI had seen quite a number of lows owing to unsustainable projects, contracts, and loans; and even surrounded itself with human rights issues and concerns of sovereignty with other nations such as India. However, the health emergency caused by the pandemic has dampened the BRI ambitions to a large extent even though Beijing is still determined to go ahead with it.

Slump in Chinese investments

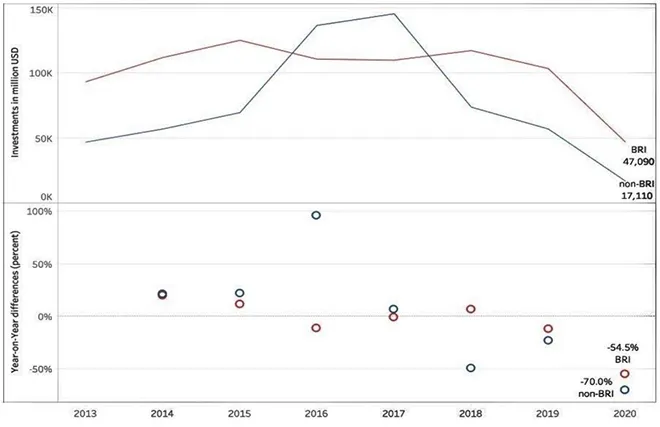

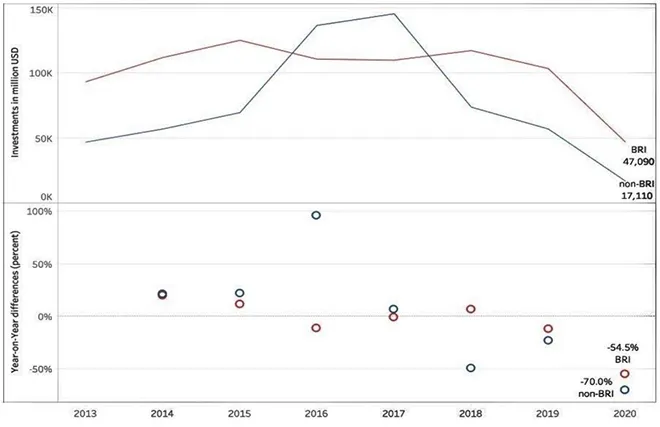

As per the global statistics, Chinese investments in the BRI countries were over US $47 billion in 2020. This was a 54.5 percent drop in investments compared to 2019 and around US $78 billion less than the total in 2015, when BRI investments had peaked. This drop in Chinese investments in BRI countries was milder than in non-BRI countries. Countries that had not signed MoUs with China within the BRI framework, witnessed an approximate 70 percent drop in Chinese investments.

Figure 1: Chinese Overseas Investments during 2013-2020

Source: International Institute of Green Finance, CUFE

Source: International Institute of Green Finance, CUFE

The impending debt crisis

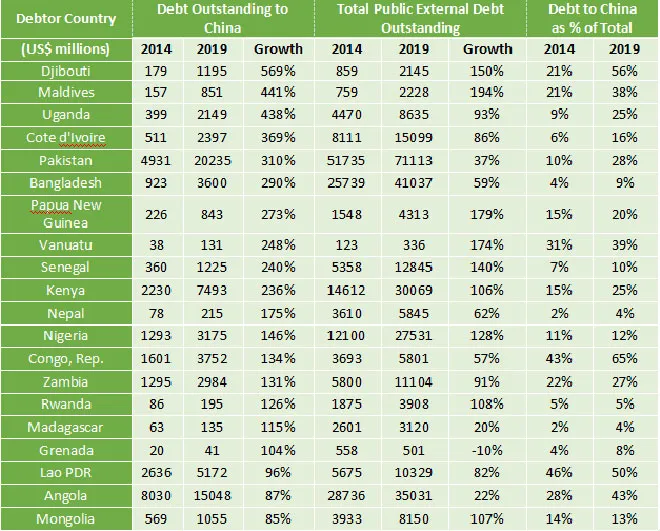

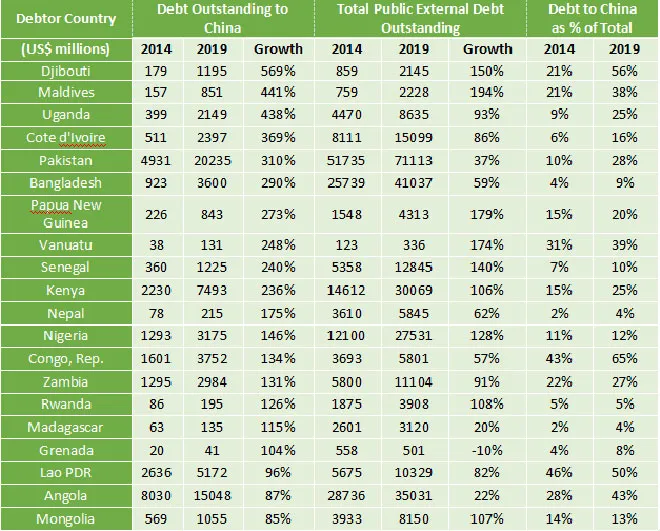

One of the core problems of BRI was the long-term debt for the recipient countries, especially in the developing and underdeveloped nations of Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Experts fear that it could lead to a debt crisis in many economies, and this stance is reinforced by the financial burden that the pandemic had brought along with it. By the end of 2019, the top countries with outstanding debt owed to China include—Pakistan (US $20 billion), Angola (US $15 billion), Kenya (US $7.5 billion), Ethiopia (US $6.5 billion), and Lao PDR (US $5 billion).

What is particularly worrisome is the fact that countries which are grappling with the double whammy of high public external debt, as well as high volumes of debt owed to China, highlight the precarious situation of their own public finances. For example, in 2019, countries such as the Republic of Congo, Djibouti, and Lao PDR have the highest Chinese debt-to-GNI ratio (0.39, 0.35, and 0.29 respectively) alongside moderately high external debt-GNI-ratio (0.60, 0.62, and 0.58 respectively), amongst 52 BRI countries that was studied in a report by the Green BRI Centre.

Table 1: Debt Outstanding to China versus Total Public External Debt

Source: World Bank International Debt Statistics; IIGF Green BRI Center (2020)

Source: World Bank International Debt Statistics; IIGF Green BRI Center (2020)

China has often leveraged its economic might to take control of the African natural resource markets, where most of the smaller nations confront significant difficulties in repaying Chinese loans. On the Asian front, where 70 percent control of Sri Lanka's Hambantota port was leased to a Chinese state-owned firm for 99 years, it reinforced China’s ‘debt-trap diplomacy’—a term coined by the international community a few years back based on increasing debts owed to China by economically vulnerable nations. Not so surprising is the fact that many countries are now queuing up to China for debt relief in the wake of domestic resource diversion, to bring the pandemic under control.

What awaits?

Recently, in mid-July this year, the foreign ministers from 27 European Union (EU) member states have moved for a new global connectivity strategy that is characterised by “a geostrategic and global approach to connectivity” for the EU. The increase in China's footprints in EU has been a major reason of concern for the continent in the last few years, especially with the Chinese FDI flows into Greece and Portugal. Hence, EU's global connectivity strategy as well as the publication of the long-awaited “EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific" document are strong signals of BRI alternatives. This also coincides with the G7’s Build Back Better World (B3W) Initiative in 2021 for global infrastructure development, to counter China’s BRI.

EU's global connectivity strategy as well as the publication of the long-awaited “EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific" document are strong signals of BRI alternatives.

The Chinese economy has some key economic issues to handle in its home ground, in addition to the pandemic. Its domestic product market faces high competition and saturation because of which it views India as one of the largest emerging markets with untapped potential. In fact, the modalities of the Indian markets are extremely similar to that of the Chinese markets, which has led Chinese investors to believe that there is ample scope to succeed if the scale economies are harnessed adequately in India. In terms of the factor markets, the labour costs in China have also skyrocketed in the last three decades which has made ‘off-shoring’ necessary for various sectors to keep product prices competitive in the global markets. Hence, in the view of China’s domestic economy as well as the global economic slump aggravated by the pandemic, if Beijing goes ahead with the BRI, it needs a more steady approach with emphasis on the healthcare infrastructure, such as by revamping the Health Silk Road component of BRI which could add renewed credibility to the BRI.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV