Introduction

Given India’s GDP growth is estimated to contract by 11.8% in 2020-21, it is clear that the economy needs a revival strategy. To ensure the inequalities of the past do not re-occur, this revival strategy needs to be inclusive and fast-paced. One of the areas that promises to be both is the care economy and one of the first steps to undertake is the identification of care workers in India.

What is care work?

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) broadly defines care work as “consisting of activities and relations involved in meeting the physical, psychological and emotional needs of adults and children, old and young, frail and able-bodied. Care workers include a wide range of workers from university professors, doctors and dentists at one end of the spectrum, to childcare workers and personal care workers at the other. Care workers also include domestic workers.” For any society and economy to survive and thrive, care work, both paid and unpaid, is extremely essential but the indispensable nature of care work was further highlighted in the pandemic, when it became difficult to proceed without the services of care workers.

The vitality of care work

Apart from being necessary for the normal day to day, care economy is a huge employer, the sector also offers serious growth potential.

Not only does the paid care work sector employ a large proportion of India’s population, especially women<1>, but given that soon India will become an aging country, the requirement of care work, especially personal, domestic and health care work will increase drastically, implying a large area of employment ready to absorb job seekers will open up.

Moreover, paid care work has always been a major source of remittances for India as many care workers tend to migrate to other countries for work. Although, the pandemic has affected their employment, it is extremely likely that as world economy revives, the need for paid care work to substitute unpaid care work will arise again. Then, a focus on care economy could also help revive and possibly increase India’s remittances from abroad.

Furthermore, since all over the world, most paid care workers are women and girls<2> and they also cater to most of the unpaid care work, focus on care economy is likely to boost the extremely low Female Labour Force Participation Rate in India. Women will not only be encouraged to work in care economy but easy access to care work will allow women who previously burdened with unpaid care work were forced to leave paid work, a chance to re-join the labour force.

In fact, an ILO report states that since demand for care work all over the world is set to surge by 2030 (due to demographic transition and urbanisation), investment in India’s care economy can possibly produce 11 million jobs in India (of which 32.5% will be by women).

The Hurdles to Cross

Historically, however, not a lot of focus has been given to care work despite its importance. This is evident from two factors - first, there is no mechanism for proper identification of care economy workers in India; second, as compared to other countries, public expenditure on care economy is extremely low in India.

The main issue of identification of care workers boils down the problem of not having a formal ‘Indianized’ definition of care economy. In the absence of a formal definition, population surveys are unable to incorporate a category for care workers, both paid and unpaid, thus, creating no possible route to reach them and implement policies aimed at their upliftment.

The negative consequences of the inability to identify are huge. For instance, the pandemic created several pushbacks for paid care workers. While, especially evident in the case of women’s unpaid care work,<3> even paid care workers faced negative consequences resulting in frontline health care workers being more likely to test positive for Covid-19, protests by Asha Workers demanding better pay, income and job losses for domestic workers and education workers.

Had there been an identification mechanism in place, it would have been possible to recognize the actual range and scope of care economy in pre-pandemic India, permitting the ability to provide adequate relief to care workers during the lockdown. Similarly, while the government is coming out with new labour codes which focus on providing social security benefits to informal workers, with no method of identification, it will be extremely hard to implement this policy to reach care workers efficiently.

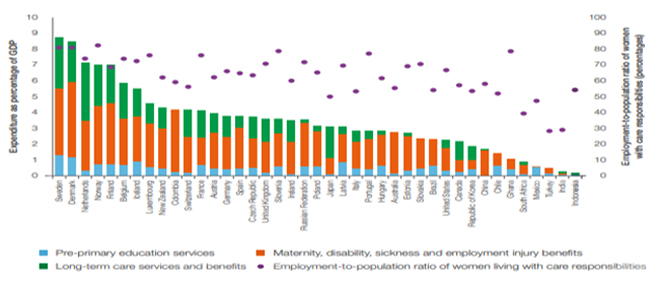

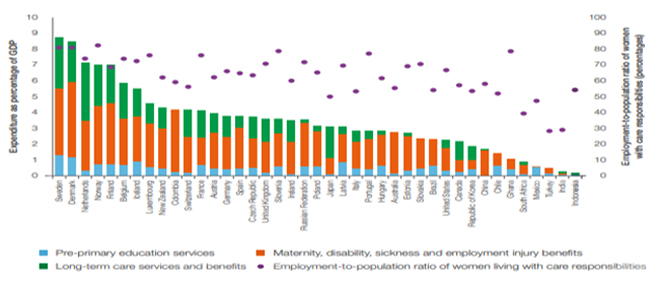

Correspondingly, the limited public expenditure (less than 1% of India’s GDP – as noted in Figure 1) and attention has created social and economic drawbacks for care economy workers. Not only has it resulted it no policy interest to generate an identification methodology for care workers but the lack of attention also often results in less than minimal wages being paid, and difficult working environment for care workers.

Figure 1: Public Expenditure on selected care policies as a percentage of GDP & Employment to population ratio of women with care responsibilities; latest year

Source: ILO Data

Source: ILO Data

The way ahead

It is, thus, imperative to create an identification mechanism for care workers thereby creating a pipeline that could be used to reach them. Once a formal definition is devised, a person that is identified as a care worker must be allotted a job card<4>. This job card will not only allow a channel to issue benefits (for instance, it will help the government to realize its social security payments to these workers as laid out in the new labour codes) but will also help create an official network of care workers.

A formal network as such could help match care givers with care seekers, create better working conditions, and produce more accountability. Furthermore, a formal definition could encourage more policy work in care economy highlighting existing gaps to be bridged to encourage more employment into care work, especially women.

Furthermore, if care work is indeed paid attention to in India’s new growth strategy, additional benefits would emerge. Formalization could help create safer environments and force compliance of issuing minimal wage, creating more value for care work. In the long term, this could help place more value on unpaid care work, in turn leading to a more equal division of work at home.

Conclusion

India’s economy needs revival and the hope is that future growth story will be more inclusive. Not only does care economy promises to be a high paced inclusive growth sector but investment in care work will help India attain its Sustainable Development Goals. However, the first step is identification!

<1> Domestic employment alone in India is estimated to range from 4.75 million (of which 3 million are women) to 80 million workers.

<2> Care work represents 19.3 per cent of global female employment

<3> With the lockdown as the access to paid care work reduced, unpaid care work was disproportionately dumped upon women

<4> Similar to the job cards held by MGNREGA workers

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source: ILO Data

Source: ILO Data PREV

PREV