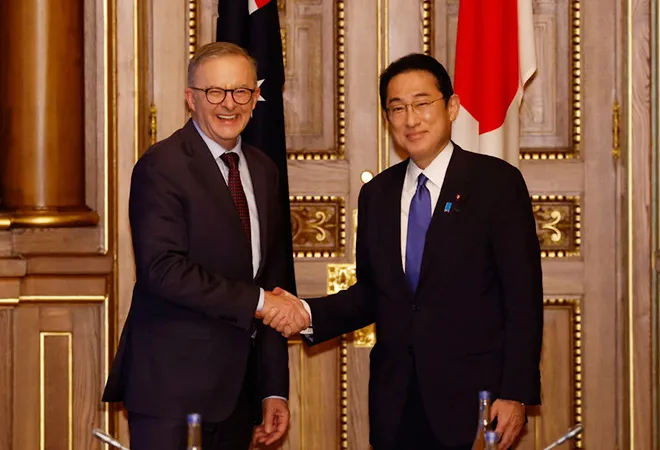

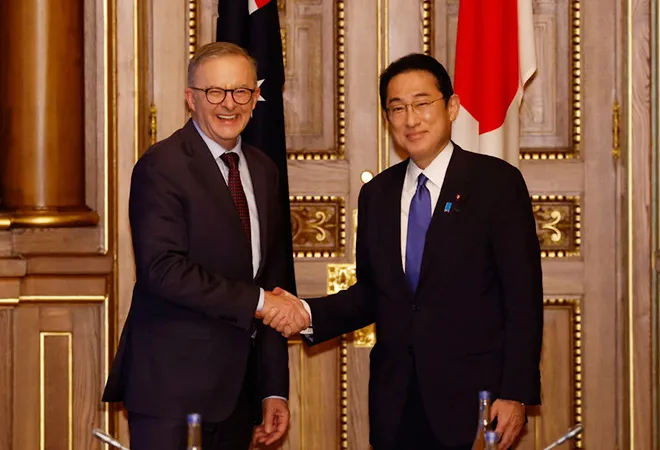

Last month, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison undertook a two-day visit to Japan. This trip on November 17-18 was not just a routine visit. It carried a great deal of significance not only for the Japan-Australia bilateral relationship, but also for the rapidly increasing relevance of the Quad group of countries. The fact that Morrison chose to visit Japan in person amidst the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, even disregarding the risk of having to face a 14-day quarantine on his return to Canberra, was a testament to the importance that he attached to his Japan visit. He was the first prime minister to be hosted by the new Japanese PM Yoshihide Suga. It was also Morrison’s first foreign visit after the outbreak of COVID-19.

Both Japan and Australia are long-standing allies of the US and, in recent years, they have stepped up their efforts to strengthen their bilateral defence cooperation as well. Japan is also a major economic partner of Australia; it is the second biggest trading partner and a big investor in Australia. Their economic relations are buttressed by a bilateral partnership agreement. It was Shinzo Abe, the previous Japanese prime minister, who, while keeping the alliance with the US as the cornerstone of Japanese diplomacy, was keen to maintain strong strategic partnerships with middle powers like Australia, India, Vietnam and Indonesia. He considered these countries very vital for the realisation of his vision of a free and open Indo-Pacific (FOIP).

One should note that both countries have been systematically deepening their security relationship since 2007, when they first signed a declaration for security cooperation. This was followed by an information security agreement in 2012, which enabled them to share confidential intelligence. In 2014, they signed an important agreement on the transfer of defence technology and equipment. Simultaneously, they also elevated their relations to a special strategic partnership.

The rise of China has driven the two countries closer together in recent years, and together with the US and India, they have promoted the FOIP strategy to ensure peace and security in the Indo-Pacific region against the aggressive economic and military assertiveness of China.

The rise of China has driven the two countries closer together in recent years, and together with the US and India, they have promoted the FOIP strategy to ensure peace and security in the Indo-Pacific region against the aggressive economic and military assertiveness of China.

Having inherited Abe’s FOIP vision, Suga started off with considerable passion to bolster it by hosting the second Quad ministerial meeting in Tokyo in early October, within a month of coming to power. He followed it up by undertaking his first foreign visit to Vietnam and Indonesia, two principal ASEAN countries whose support to FOIP would matter a lot.

The significance of Prime Minister Morrison’s visit should be seen against this backdrop. He went there to deepen the bilateral security partnership by signing a reciprocal assistance agreement (RAA). One of the compelling reasons for this, according to some analysts, was to avoid giving China an opportunity to exploit any strategic uncertainty that could arise in the complicated transition process from President Donald Trump to Joe Biden. He was keen to clinch an agreement that would facilitate joint military exercises, strengthen inter-operability by easing restrictions on Japan Self-Defence Forces and Australian military forces while they are staying in each other’s territories. It would remove all administrative formalities needed for one country to send troops for drills on the soil of the other country. It would also simplify the process of transporting weapons and vehicles between the two sides facilitating smooth mutual cooperation. The agreement will open new opportunities of cooperation between Japan’s ground Self-Defence Forces and its Australian counterpart.

It is important to note that negotiations for this agreement were going on for a number of years, but they were stuck on a touchy legal point related to Australia’s sensitivities to Japan’s position on the death penalty. What would happen to an Australian soldier involved in a serious offence outside of his official duties? Since Japan still has the death penalty, Australia is quite worried about its application. However, in the larger interests of regional security, both countries finally found a device that would enable them to examine such incidents on a case-by-case basis, though the details of the mechanism are still to be announced.

The agreement needs to be formally signed by both countries before it comes into effect. The two prime ministers have instructed their governments to speed up the process of signing the agreement. It is to be noted that the agreement also needs to be ratified by the Japanese Diet.

This is the first time that Japan will be entering into an agreement of this kind since 1960, when Tokyo signed the Status Of Forces Agreement (SOFA) with the US, which has since then been a source of frequent tension between Tokyo and Washington. But SOFA is very different from the RAA in the sense that the former permits US forces to stay in Japan on a permanent basis, whereas the latter is concerned with the temporary presence of Australian and Japanese forces in each other’s countries.

SOFA is very different from the RAA in the sense that the former permits US forces to stay in Japan on a permanent basis, whereas the latter is concerned with the temporary presence of Australian and Japanese forces in each other’s countries

Apart from finalising the RAA, both leaders also reaffirmed their strong commitment to the security and stability of the Indo-Pacific region. In particular, they expressed their “strong opposition to any coercive, unilateral attempts to change the status quo” in the South China Sea area. They urged all countries to respect freedom of navigation and overflight in the South China Sea and they further underscored the need for a code of conduct in the area that would be consistent with international law as embodied in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). They also strongly criticised China’s increasing maritime activities in the East China Sea where Chinese vessels regularly intrude into Japanese territorial waters surrounding the Senkaku Islands.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV