We also face a new threat. The next epidemic has a good chance of originating on a computer screen of a terrorist intent on using genetic engineering to create a synthetic version of the smallpox virus or a contagious and highly deadly strain of flu. So, the point is that we ignore the strong link between health security and international security at our peril. Whether it occurs by the hand of nature or at the hand of a terrorist, epidemiologists show through their models that a respiratory-spread pathogen would kill 30 million people in less than a year. And there is a reasonable probability of that taking place in the years ahead.

We also face a new threat. The next epidemic has a good chance of originating on a computer screen of a terrorist intent on using genetic engineering to create a synthetic version of the smallpox virus or a contagious and highly deadly strain of flu. So, the point is that we ignore the strong link between health security and international security at our peril. Whether it occurs by the hand of nature or at the hand of a terrorist, epidemiologists show through their models that a respiratory-spread pathogen would kill 30 million people in less than a year. And there is a reasonable probability of that taking place in the years ahead.

– Bill Gates talking at Munich Security Conference in 2017.

As the novel coronavirus – termed 2019-nCov, and later SARS-Co V-2 – continued its spread beyond the borders of China, the World Health Organization was forced to call it a

public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) on the 30

th January 2020. Understandably, the outbreak has also spawned many conspiracy theories, which rely heavily on parts of Bill Gates’ premise,

mostly with zero evidence. WHO has

named the new disease Covid-19, short for “coronavirus disease 2019.” Many countries have limited the travel of their citizens to China, Chinese cities are locked down, trade to and from China has taken a hit, and the economic costs to China have been termed

enormous already. Some forecast that global economic growth in 2020 will be

curbed by up to 0.3%, while the first quarter growth of the US economy itself could be reduced by up to 0.4%.

International Health Regulations (IHR) were agreed upon by the global community to improve

detection and reporting of potential public health emergencies worldwide. IHR (2005) requires that all countries have the ability to

detect, assess, report and respond to public health events with potential spillover effects across borders. Under IHR, once a WHO member identifies a potential event, it must assess the public health risks and notify WHO. Since IHR came into being, WHO has declared four PHEICs namely, H1N1 influenza (2009), Polio (2014), Ebola (2014) and Zika virus (2016). Covid-19 is the fifth time a PHEIC is declared by the WHO.

There have been

some complaints that China dragged its feet before it reported the outbreak to the international community, but China’s efforts to minimize spread have largely drawn praise from global players since. Indeed, an epidemic that demands very strict containment measures is perhaps one rare instance when the Western world applauds an authoritarian regime. China’s general disdain for human rights has certainly contributed to its “

setting a new standard for outbreak response”. Of just above

43,000 global Covid-19 cases, around 42,700 are still within Chinese borders. All the deaths (1017), barring one, have been on Chinese soil.

The heavy-handed Chinese response has certainly limited global spread of the disease. Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the Director-General of the World Health Organization repeated many times during the

press conference that declared Covid-19 a PHEIC that WHO is declaring it a global health emergency not because of what is happening in China, but because the virus is spreading to countries with ill-prepared, "weak" health systems. The disease spreading to countries like India which are quite unprepared to contain a potential spread has certainly contributed to the WHO’s decision to declare it a PHEIC.

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare in India has termed the situation within the country

“under control” presently, and states were asked to remain alert and vigilant with efforts generating community level awareness taking centre stage. Screening of passengers for Covid-19 symptoms is going on in 21 airports, 12 major Seaports and border crossings across the country. According to ministry communication,

2148 flights and 232613 passengers from China have been screened so far. Despite China’s

initial reluctance, India managed to evacuate on the 1

st February

hundreds of Indians who were stranded in Wuhan due to the outbreak.

Almost two weeks after the evacuation, the government reported that all Indian evacuees from Wuhan – 645 of them-

have tested negative for 2019-nCoV. Over 11500 individuals are presently

under community surveillance in 34 States/UTs and contact tracing is going on. As of now, 1632 samples from suspected patients have been tested from across the country of which

three samples have tested positive; all from the state of Kerala. Interestingly, reports indicate that

all three patients are medical students undergoing training in Wuhan.

Latest data indicates that about 82% of cases are mild, 18% cases are severe, of which 3% require intensive care; and that the fatalities are mostly old patients and those with pre-existing conditions. Many medical personnel are getting affected as well. Since the rapidly spreading Covid-19 is also a relatively mild infection with generic symptoms, many cases have not been counted and there is a high likelihood that the severity is overestimated, and it triggers panic. On the other end, in weak health systems like India, an ineffective surveillance system may not allow for aggressive case detection, thus underestimating the true burden.

Even for Nipah with a

case fatality rate of around 80% , India has a history of calling it a “mystery fever”, and moving on, and finding the

real cause only later, retrospectively. With a

much milder Covid-19, missing a few cases or even a cluster of cases will be normal in many Indian states. In fact, it has to be expected. Given the Indian climate and air pollution levels, a few cases with mild respiratory disease getting drowned in the usual flood of mild respiratory diseases across the country is a distinct possibility. There are indications that

higher temperatures may slow transmission of the new virus, which may be delaying its spread in India. However, instead of strengthening systems, Indian public health establishment has often chosen a knee-jerk response to the media frenzy around outbreaks, as seen in Nipah’s case, where it unfortunately

clamped down on foreign collaborations of Indian research institutions.

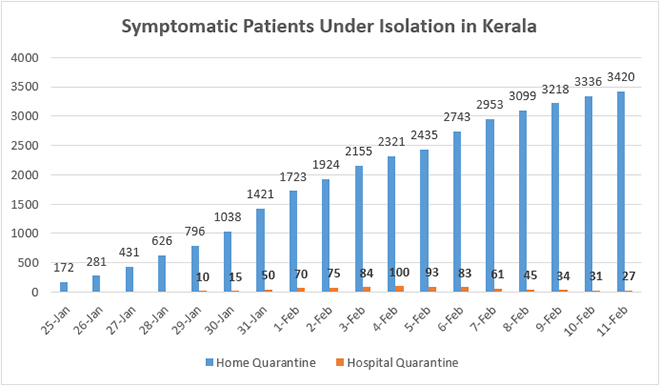

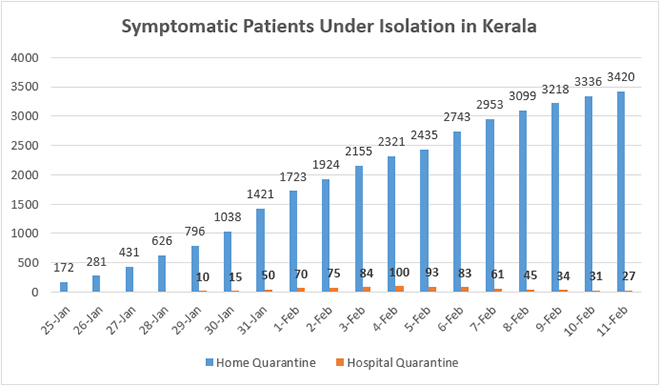

Given this context, Kerala’s response to Covid-19 has been remarkable. Kerala has been publishing

daily updates about quarantine, tests and hospitalisations. Reportedly, two out of the three patients infected with Covid-19 have

now tested negative. However, given the close linkages

between Kerala and Wuhan, both hospital based and community based quarantine efforts are actively on. Of the 11,500 individuals presently

under community surveillance in 34 States/UTs across India, around one-third are in Kerala alone. A day-wise graph of hospital based and home-based surveillance is given below.

Source: Directorate of Health Services, Kerala

Source: Directorate of Health Services, Kerala

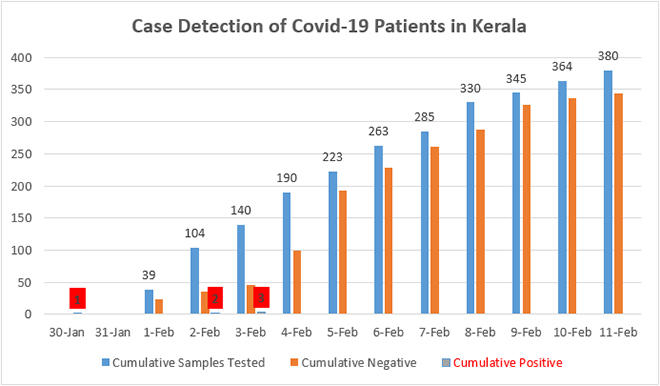

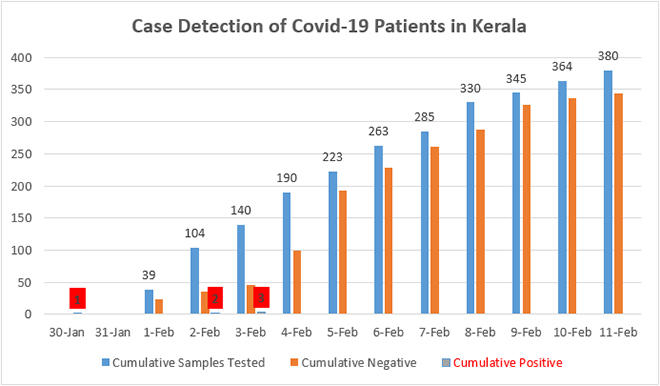

Of the suspected patients kept under isolation in hospitals, many are being discharged and shifted back to community surveillance as test results are negative and symptoms subside. At its peak, on 4

th February, around 100 suspected patients were kept in various hospitals across the states; however, now the number is only 27. A total number of 380 samples were tested for Covid-19 until today, and 344 have already proven negative, as the next graph shows.

Source: Directorate of Health Services, Kerala

Source: Directorate of Health Services, Kerala

On the 7

th February, Kerala government

withdrew the 'state calamity' warning it issued earlier in the wake of three cases of Covid-19, as no new positive cases of infection were detected despite active surveillance. Although the Centre suggested a quarantine period of 14 days, Kerala government is taking no chances and

quarantining people for 28 days as a precautionary measure. If current trends continue, the state expects to be

free of 2019-nCoV by early March, which seems overtly optimistic, unless the global situation improves drastically.

Measures like contact tracing will have only limited impact once the spread beyond China becomes large enough. Judging from the sustained transmission within China and even in countries like Japan, Singapore, Korea and Germany, it is just a matter of time before the disease becomes truly “global”. Given China’s sphere of influence, it is likely that we will soon have cases reported in Africa, as the limiting factor currently seems to be

diagnostic capacity. Sustained transmission makes travel bans less effective, and at best can buy more time for health systems to be ready for impact. Singapore, with a well-functioning public health system, is already reporting

community level transmission.

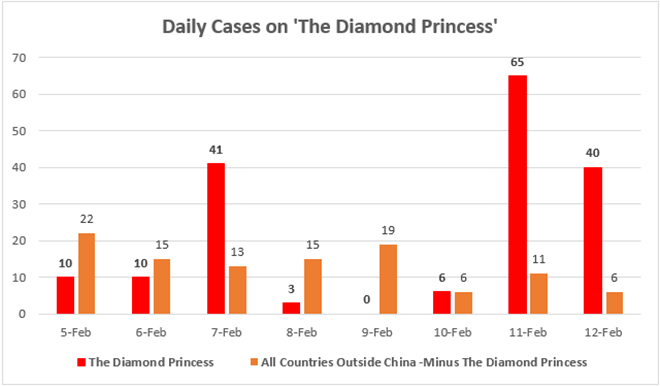

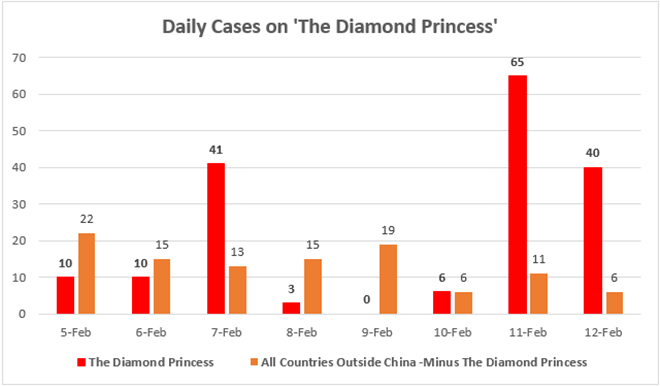

The unfolding story of the cruise ship

The Diamond Princess, off Japanese coast is instructive. In terms of positive cases of Covid-19,

The Diamond Princess has been termed as “the second largest country in the world right now behind only to China”. The following graph shows clearly what 2019-nCoV can do in a relatively crowded space with space constraint. Experts have termed

passenger population density as a reason for the rapid spread of the virus. Sounds very familiar, if one knows Indian urban spaces and hospitals. Therefore, the cruise ship is a particularly interesting part of this outbreak for countries like India. As of 12

th February, of a total of 441 confirmed cases outside China, a staggering 175 are on

The Diamond Princess alone

. Recent reports indicate that on 13

th February alone,

44 more travelers have tested positive,

including Indians.

Countries like India will have to start thinking hard about a shift in strategy from containment to mitigation at some point. Given the fact that Covid-19 as of now is a relatively mild infection, many positive cases across India may be missed through

misdiagnosis or missed diagnosis. However, if there is sustained spread and panic sets in, irrespective of the relatively low case fatality rates, Covid-19 can kill many in India through two pathways. First, older and chronically ill can get potentially fatal Covid-19 infection at hospitals where they visit for routine treatment, and second, panic stricken common flu patients can crowd hospitals and overwhelm the health care delivery capacity of private and public sector. The latter scenario can see many people in real need of advanced care getting left out. If there is community level transmission in India, the resulting societal disruption will be immense, unless the government takes sufficient measures, and be ready for any eventuality in the coming months.

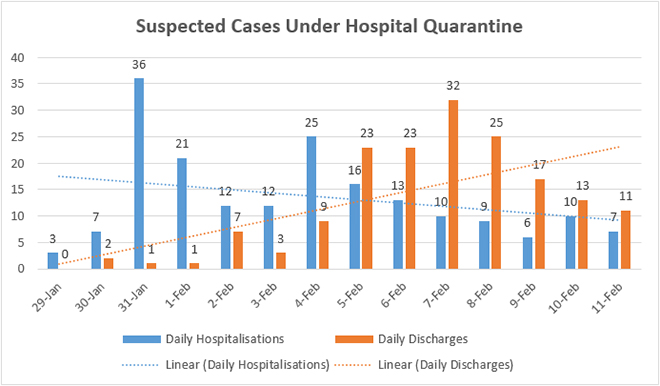

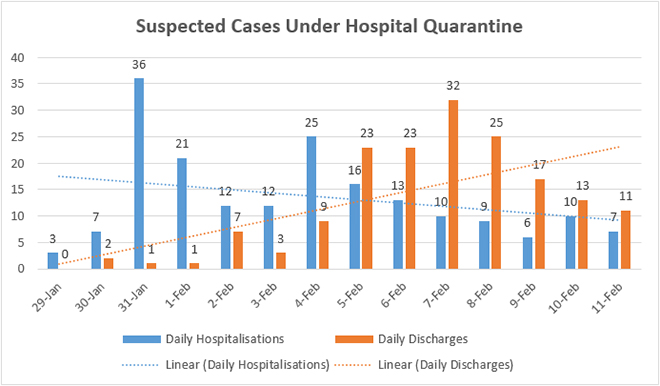

Source: Directorate of Health Services, Kerala

Source: Directorate of Health Services, Kerala

As the above graph shows, with strict travel restrictions and other measures in place, daily hospitalisations of suspected cases have shrunk considerably in Kerala, and number of patients daily discharged after a negative report and subsided symptoms outnumber the former consistently. Timely dissemination of surveillance data was an effective way in which the government of Kerala managed to keep panic under check, and gain the confidence of the community. The state looks ready for any possible spread even at the community level.

As the country braces for Covid-19’s impact, the government of India should ensure regular release of state-wise data on quarantine and tests, which it compiles on a daily basis, so that media speculation is avoided. With Nipah, and now Covid-19, Kerala provides a template for the Central government, of calm and alert public health problem-solving. Perhaps over and above what Kerala is doing on social media, the Central government can effectively leverage WhatsApp too to allay fears, as Covid-19 spreads across the world.

Shreya Behal helped with compilation of data.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

We also face a new threat. The next epidemic has a good chance of originating on a computer screen of a terrorist intent on using genetic engineering to create a synthetic version of the smallpox virus or a contagious and highly deadly strain of flu. So, the point is that we ignore the strong link between health security and international security at our peril. Whether it occurs by the hand of nature or at the hand of a terrorist, epidemiologists show through their models that a respiratory-spread pathogen would kill 30 million people in less than a year. And there is a reasonable probability of that taking place in the years ahead.

– Bill Gates talking at Munich Security Conference in 2017.

We also face a new threat. The next epidemic has a good chance of originating on a computer screen of a terrorist intent on using genetic engineering to create a synthetic version of the smallpox virus or a contagious and highly deadly strain of flu. So, the point is that we ignore the strong link between health security and international security at our peril. Whether it occurs by the hand of nature or at the hand of a terrorist, epidemiologists show through their models that a respiratory-spread pathogen would kill 30 million people in less than a year. And there is a reasonable probability of that taking place in the years ahead.

– Bill Gates talking at Munich Security Conference in 2017.

Source:

Source:  Source:

Source:  Countries like India will have to start thinking hard about a shift in strategy from containment to mitigation at some point. Given the fact that Covid-19 as of now is a relatively mild infection, many positive cases across India may be missed through

Countries like India will have to start thinking hard about a shift in strategy from containment to mitigation at some point. Given the fact that Covid-19 as of now is a relatively mild infection, many positive cases across India may be missed through  Source:

Source:  PREV

PREV