The 9th China-Central and Eastern European Countries Summit in February this year witnessed President Xi Jinping emphasise the growth of trade between China and the Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries, its intention to import more than US $170 billion of goods from the region, and further promotion of vaccine cooperation. At the same time, six out of the 12 participating EU member states sent their ministers, not heads of state, as representatives for the Summit. This may indicate the differing levels of importance the two groupings have assigned to the cooperation—with China hoping the framework moves forward while the CEE countries grow dissatisfied with the engagement’s outcome.

Established in 2012, the Sino-CEEC Cooperation is an initiative to promote economic and trade cooperation between China and the 16 member states, namely, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, and Slovenia, with Lithuania recently exiting the partnership. Central and Eastern Europe stands at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, a strategic location between Russia and the Middle East. Its geopolitical significance was first brought to attention by Halford Mackinder with his Heartland Theory, “Whoever rules East Europe commands the Heartland; whoever rules the Heartland commands the World-Island; whoever rules the World-Island commands the World.

Central and Eastern Europe stands at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, a strategic location between Russia and the Middle East. Its geopolitical significance was first brought to attention by Halford Mackinder with his Heartland Theory.

A slightly different cooperation

The cooperation has faced heavy criticism through the years, with European diplomats considering it a Chinese tool for divide and rule. On the other hand, there has been a growing discontent amongst the CEE countries due to the mellow outcome of their economic engagement with China, thus, reducing China’s influence in the region. Ten years since its inception, the question surrounding the 16+1 initiative remains the same; is it being used as a divide et impera tool by China, or is it just a convenient cooperation receiving unwarranted attention?

In a way, it is a significant platform for promoting the Belt and Road Initiative. The Central and Eastern European countries act as a strategic link between Western Europe and Asia, thus making the 16+1 initiative conducive towards the success of the BRI. The difference lies in the structure and that China does not have as much control as it usually does with partner countries. Additionally, BRI focuses mainly on the digital sector, connectivity-transport, and energy, while the 16+1 is multi-sectoral and multi-actor.

The depth of China’s geo-economic influence

Despite the fundings provided by the European Union and international financial institutions, there remains a financing gap in the CEE countries that cannot be filled without acquiring resources from third countries. This is where China steps in, presenting an attractive package void of any institutional obstacles and with swift implementation.

Politicians on both sides tend to inflate the impact that China’ investments have had in the region. The majority of the member states have had relatively low trade with China, its unbalanced nature creating an increasing trade deficit worth US $75 billion.

In terms of infrastructure development, China-CEEC cooperation has been divided due to the EU membership. The five non-EU countries, Serbia, Albania, Macedonia, Montenegro, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, have warmly welcomed China-funded projects worth about 6 billion Euros. Loans from the Exim Bank of China have been used to fund highways, coal-fired power stations, and railways in the Western Balkans. The reason behind the popularity of the Chinese funding model is the bleak nature of the financing from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the World Bank, and the Russian credit line for Serbia.

On the contrary, none of the infrastructure projects announced for the remaining 11 countries, who are EU members, went beyond paper and political declarations. Projects signed as early as 2013 have not even begun, the Belgrade-Budapest railway being the only exception. Chinese investment remains modest at 3 percent of China’s total FDI in the EU in 2019, a level still well below the region’s weight in the GDP of the EU. While China has successfully obtained tenders for infrastructure development projects, it can act as merely a contractor but not as a lender or an investor.

The reason behind the popularity of the Chinese funding model is the bleak nature of the financing from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the World Bank, and the Russian credit line for Serbia.

The reason behind the member states’ reluctance is the incompatibility of the Chinese funding model with EU law. Secondly, unlike its Western Balkan counterparts, Chinese investment is just another option for the EU countries, not their saving grace, because they have an attractive alternative in the form of cheap and transparent loans from the European Investment Bank.

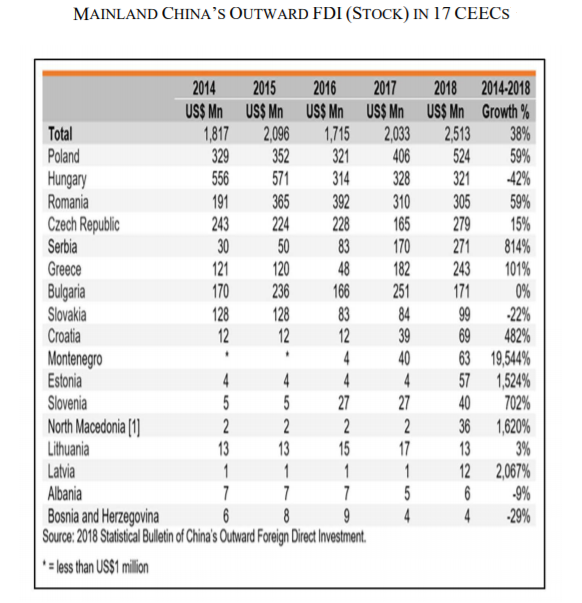

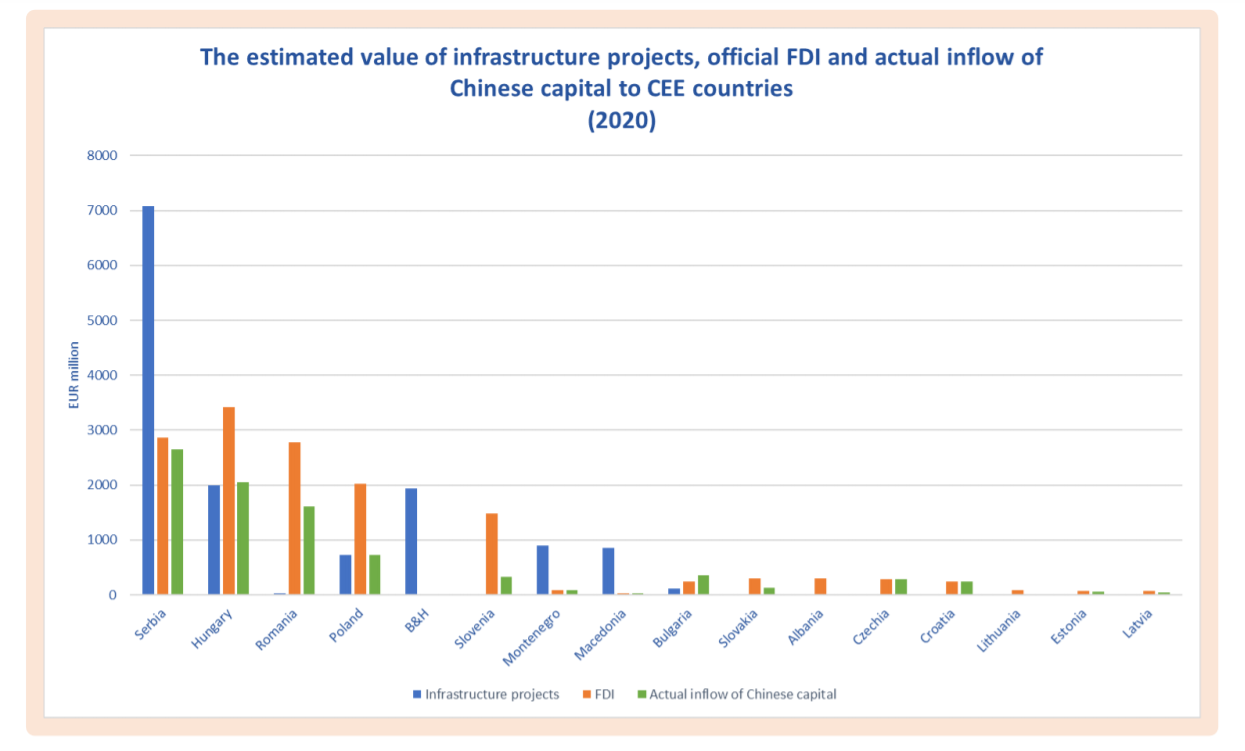

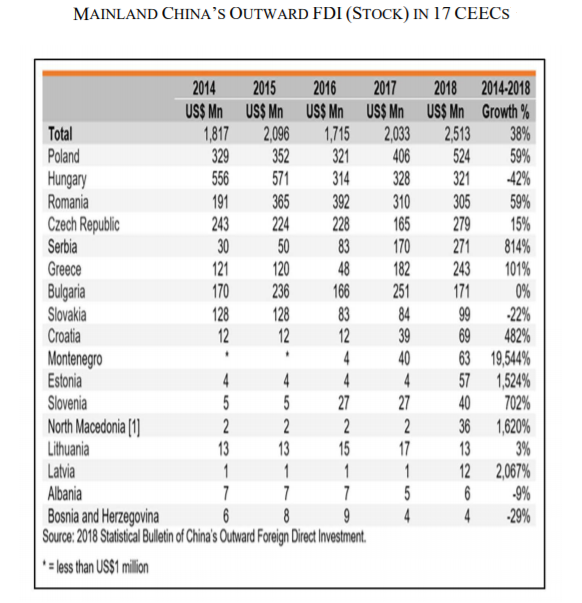

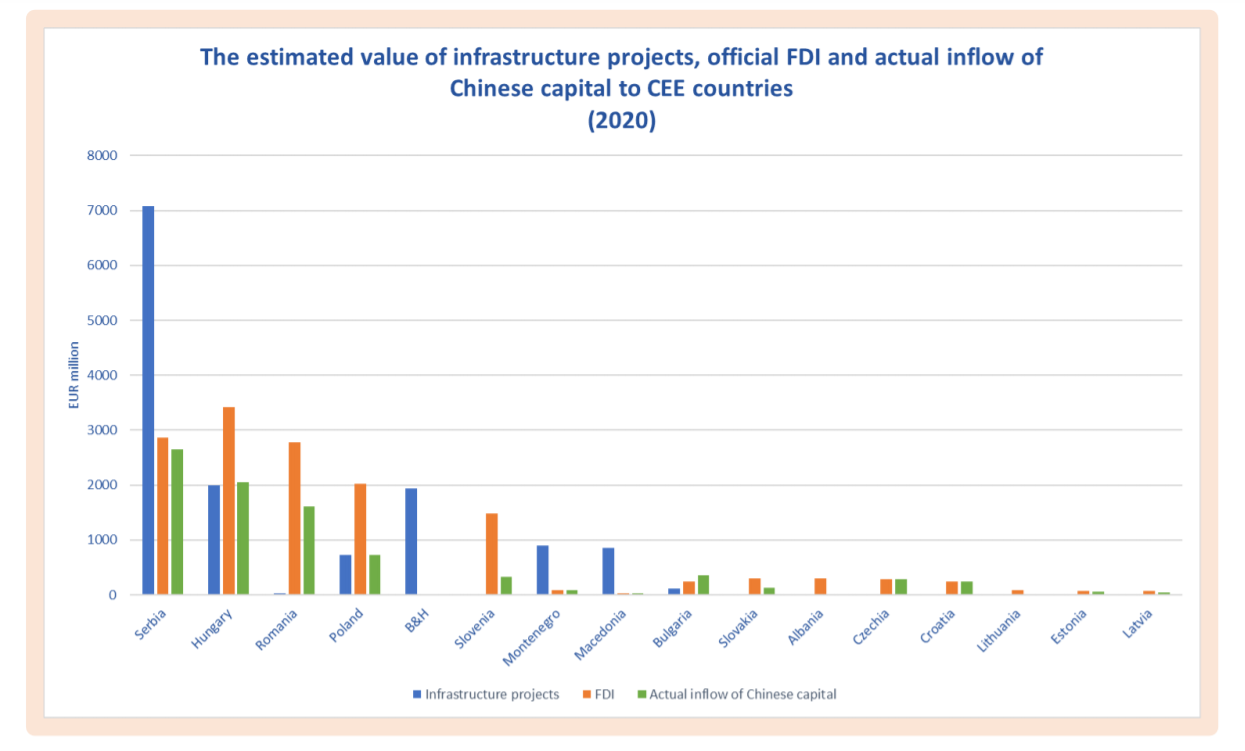

The table below indicates how while there are generous amounts of investment, FDI is not synonymous with the actual inflow of capital. All Chinese-owned companies are considered a part of Chinese direct investment. This implies that when a Chinese company acquires an MNC, the branches of that MNC present in the CEE countries would henceforth be considered Chinese investment.

Source: Central and Eastern European Center for Asian Studies

Source: Central and Eastern European Center for Asian Studies

Why CEEC?

The cooperation is viewed by many as a tool to divide the EU. Doubts have arisen because China offers loans, not investments. The credits are provided by state-owned institutions that usually require sovereign guarantees, thus, shifting the investment risk onto the borrowing country. A classic example is the highway project in Montenegro, which has burdened the country with massive debts to China that amount to more than a third of the Montenegrin government’s annual budget.

A larger part of the initiative includes people-to-people participation in tourism, think tank cooperation, young leaders’ forums, and literature translations. It grants direct access to the people, thus, helping China form relations with future decision-makers. There has been increased participation of the Chinese Communist Party in China-CEEC relations at the local levels. Direct contact with these parties helps the CCP circumvent diplomatic channels and official government contacts.

The EU has been vocal about its reservations regarding the initiative and its lack of transparency by calling on the 16+1 participants to ensure that the format “enables the EU to have one voice in its relationship with China” and doesn’t compromise national and European interests. They have also materialised their concerns by formulating a screening mechanism to evaluate future FDIs in the EU member states. Although China is not the only investor in the CEE region, this step has been interpreted as being created chiefly to keep a tighter check on future Chinese investments. The EU has also criticised the Western Balkan states, warning them that stronger cooperation with China would take them further away from the prospect of an EU membership. Additionally, attention should be paid to the discrepancies in the screening processes of the CEE countries.

The EU has been vocal about its reservations regarding the initiative and its lack of transparency by calling on the 16+1 participants to ensure that the format “enables the EU to have one voice in its relationship with China” and doesn’t compromise national and European interests.

Accusations of the region being a ‘trojan horse’ emerge from the fear of growing Chinese political influence on participating countries. In July 2018, former European Commissioner for European Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations, Johannes Hahn, warned of China transforming the Western Balkans into Trojan horses that would eventually be EU members. In June 2017, Greece blocked an EU statement at the UNHRC which criticised China’s human rights record. A few months before that, Hungary had refused to sign a letter that denounced the torture of detained lawyers in China. Although an alarming incident, these events have been individual instances rather than a common trend. On the contrary, CEE countries have been growing skeptical of their cooperation with Beijing. This can be witnessed by how most of these states are taking stern steps towards strengthening their 5G security and the Romanian nuclear reactor deal cancellation.

Consequently, accusations about a Trojan horse augment the sense that, unlike their Western counterparts, the CEE countries are unreliable and not capable of promoting EU interests when engaging in external relations. It is ironic to criticise the CEE states for doing precisely what Germany and France are doing—pursuing their national interests when engaging with China. It is imperative to curb this mistrust, and the internalised east-west division or the European Union might weaken itself, causing more problems for itself than China would.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV