This article is part of the series Colaba Edit 2021.

This article is part of the series Colaba Edit 2021.

Corporations with cross jurisdictional presence are not a recent phenomenon. According to Philip C. Jessup in his book A Modern Law of Nations, the Dutch East India Company established in 1602 is a prime example of conglomerates with a global presence and the “power to make war and peace”. Over centuries, corporations became a preferred form of organising economic activity and many carry influence that often surpassing that of some smaller states. The economic power of multinational enterprises (MNEs) allowed them to access markets with ease and to disperse production processes across the globe. This was further facilitated by the liberalisation of newly independent countries in the 1990s. With time, the production process itself transformed such that labour and capital became less important for the scaling of operations. MNEs now offer services through digital presence, mainly own intangibles assets and, more importantly, do not owe economic allegiance to the countries in which they are based.

As a result, many large corporations work their way around tax structures in individual countries to minimise their global tax liabilities. Often, this adversely affects the tax base of developing countries that attract foreign investment. Therefore, international tax law—written for a time when corporations were allies of imperial power and had to physically locate operations in markets—needed an overhaul. To adapt to reality, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) initiated the base erosion and profit shifting programme in 2013. Part of the agenda was to create a new basis for taxing digital companies in markets where no office or assets were located. In 2021, the broad contours of the plan, labelled as “global tax deal”, were finalised. It is increasingly clear that issue is not just one of fixing the century-old tax system but also that of redistributing taxing rights.

The economic power of multinational enterprises (MNEs) allowed them to access markets with ease and to disperse production processes across the globe.

What Needed Fixing

Tax policy sought to fix the problem with new-age conglomerates—they are large monopolies that do not pay taxes where they create value. A debate ensued on factors that contributed to these supernormal and undertaxed returns. In 2018, the OECD released a report acknowledging that many MNEs gain mass without scale and that users or their data contribute to profits. Yet, such acknowledgement did not automatically translate into a globally acceptable solution. It was stressed that it is best to work within a consensus-based framework and therefore, 137 countries laboured to find common approaches over the next three years.

At the heart of the problem are frictionless capital flows and liberal trade regimes that make it possible for companies to locate production, assembly, and sales activities in different jurisdictions, thus confounding the allocation of profits and their taxation. This is primarily since companies are able to move profits by inflating the value of intracompany transactions such that low tax jurisdictions report a higher share in corporate incomes. While the principle of arm’s length ensured that companies priced intracompany transactions in a manner akin to comparable transaction between unrelated parties, in practice, the principle vitiated primarily due to the lack of comparable transactions.

More importantly, large tech companies work with minimal physical infrastructure in markets. For instance, Booking.com does not own any hotels, AirBnB has no real estate and Uber has no fleet of vehicles. In 2018, Apple reported only 11 percent of its assets as tangibles. The OECD estimates that intangibles—which includes superior brand value, sophisticated distribution strategies or organisational capital—account for 27 percent of the income in global value chains. In some industries, this is realised in the final stages of marketing and distribution, often carried out in developing countries. The contribution of the intangibles remains enmeshed with traditional functions, and it is difficult to ascribe value to the assets, let alone their functions.

This is primarily since companies are able to move profits by inflating the value of intracompany transactions such that low tax jurisdictions report a higher share in corporate incomes.

Therefore, two main infirmities of law needed to be fixed—one, the company with no physical presence servicing a large market should be considered as present for tax purposes; and two, the profits are properly attributed to the market and the intellectual property. No agreement was reached on either of these but instead “value creation”, a rather ill-defined term, became the centrepiece of the international reform. It was clear that while developing countries wanted a higher share in tax, the residence countries, including the US, stressed that only a part of the returns or the residual returns belonged to markets. As the proposal began to take shape, market countries reached a compromise. They accepted a slice of the profits considered as non-routine—a concept with no economic basis. Eventually, politics assumed priority over economics.

The Solution

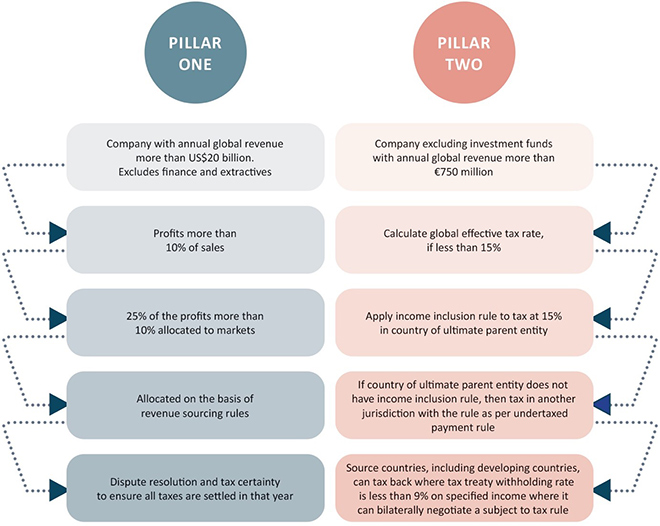

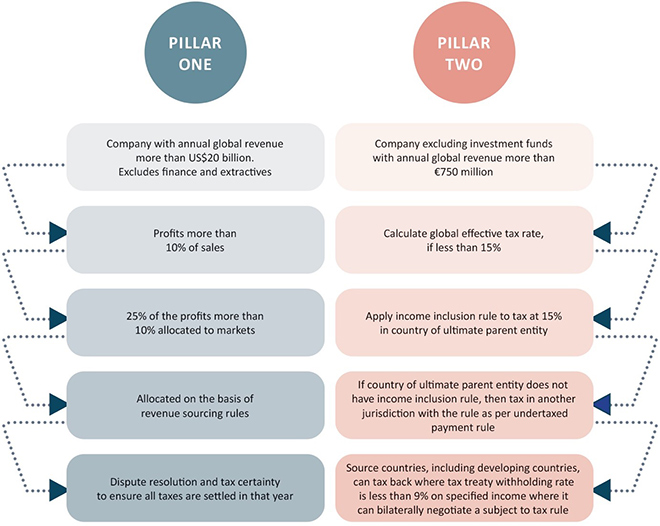

The OECD’s approach to reform changed over time, from a modest goal of fixing loopholes that facilitate tax avoidance to the more fundamental, yet contentious, historical issue of taxing rights over such incomes. In 2019, the OECD declared that it would address, without prejudice, the allocation of taxing rights and taxation of digital companies under pillar one and to address remaining tax avoidance under pillar two (see Figure 1 for a simplistic representation of the proposal). As per the pillar one proposal, a company with global revenues exceeding US$20 billion, except for those in financial and extractives sector, will have to allocate 25 percent of profits in excess of 10 percent to markets with which it has an economic nexus. This nexus will be established based on revenue sourcing rules and the proposal will be administered by a panel of international tax administrators. The pillar two proposal, on the other hand, will tax back profits of MNEs with global sales more than €750 million (US$850 million) excluding investment funds, and with global effective tax rate less than 15 percent. The first right to tax these profits will be in the country of ultimate parent entity (UPE) for which countries where UPE operates may adopt an income inclusion rule (IIR). Further, low withholding rates in tax treaties also allows companies to reduce their effective rates, in order for source countries to tax back any income on rate of tax withheld is less than 9 percent it will have to bilaterally negotiate a subject to tax rule (STTR). So, while an IIR can be implemented independently and does not require consensus approach, STTR, which of interest to developing countries, will require bilateral negotiations.

The OECD’s approach to reform changed over time, from a modest goal of fixing loopholes that facilitate tax avoidance to the more fundamental, yet contentious, historical issue of taxing rights over such incomes.

Figure 1: Pillar one and Two Proposals by OECD

Multilateral negotiations continued, albeit with uncertainty over whether the US would join the process. This encouraged countries to look for interim alternatives until an acceptable global solution was reached. India was among the first to apply the equalisation levy and soon many others, including the UK, France and Spain, followed. This further stirred controversy as the US began investigations under its US Trade Act 1970 to establish if these levies were discriminatory and threatened to apply retaliatory tariffs. As the Joe Biden administration assumed office in the US, the need to fund a domestic spending programme spurred the country to join the negotiations wholeheartedly. It was not just to fix the global tax system but also to be part of the programme to fix its own tax system while ensuring there were no incentives to offshore. In October 2021, 136 countries endorsed the plan to tax companies with more than US$20 billion as per the new rules of tax. The OECD’s reform, which initially focussed on taxing digital companies, became about taxing the biggest companies and a coordinated increase in corporate tax rates.

The details of the final proposal are awaited but the available information on the broad contours suggest that, upon ratification, the 136 countries will adopt a new complicated law for taxation of large companies (with sales revenue exceeding US$20 billion for pillar one and €750 million for pillar two), while the old or conventional rules will apply to all other companies. It is also likely that based on the thresholds, a company may qualify in one year and then drop off in the next. As per the proposal, the qualifying companies will share a fourth of their global profits in excess of 10 percent with markets where they operate. This will be based on revenue sourcing rules that include geolocation of users. In addition, countries will raise their effective tax rates to 15 percent, subject to many exclusions and caveats.

The OECD’s reform, which initially focussed on taxing digital companies, became about taxing the biggest companies and a coordinated increase in corporate tax rates.

Way Forward

It is clear that the reform that began by addressing tax challenges from digitalisation is now one of taxing MNEs better. After decades of reluctance to address tax competition, the OECD now appears to have changed its agenda and approach at the behest of developed countries. The modus operandi of businesses has transformed radically over the last century. In trying to keep pace with this reality, the OECD proposal mimics the complexity of corporate structures, even though the reform was pushed on the promise of simplicity. This can be attributed, in part as well, to the many compromises to make the proposal agreeable to 137 countries.

Developing countries are co-opted yet again with the promise that they will gain tax revenues, but early estimates suggest the contrary for India. In fact, it is possible that the revenue from current levies may exceed those from pillar one for countries like India. Nevertheless, threat of retaliatory tariffs loom as the US seeks to protect large tech companies that are its residents.

In sum, while a lot has changed, the parallels with the past cannot be missed. The MNEs continue to hold sway as much as the global power balance remains tilted in favour of developed countries. Yet, the global tax deal is also proof of the influence of market countries, such as India. Today, India accounts for 12 percent of global digital market buyers. If it seeks a simpler and fairer solution, it can choose to explore alternatives such as the withholding on automated digital services recommended by the UN.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This article is part of the series

This article is part of the series

PREV

PREV