The Tatmadaw’s

outreach to Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs) in Myanmar for peace talks has drawn much domestic and international attention. The rare conciliatory tone towards rebel groups could be driven by growing international pressure to focus reconciliation efforts as constant fighting with these groups has resulted in heavy losses. Although many resistance groups adopted a wait-and-watch approach after the military takeover in 2021, the junta has managed to convince 10 out of 21 EAOs (both signatories and non-signatories to the 2015 nationwide ceasefire agreement) to enter into a ceasefire—mostly those that are not in a direct conflict with the regime.

Both SSA and UWSP have sought to further consolidate their positions in the Shan state amidst the ongoing competition amongst the EAOs there.

The Tatmadaw’s engagement with the EAOs is more on an individual basis rather than on a group level. The country’s Army General Min Aung Hlaing held individual meetings in May 2022 with leaders of the Restoration Council of Shan State (RCSS), the Shan State Army-South (SSA-S), and the United Wa State Party (UWSP). Both SSA and UWSP have sought to further consolidate their positions in the Shan state amidst the ongoing competition amongst the EAOs there. While the SSA is

facing resistance from other rebel groups in the state, the UWSP has a stronghold in areas under its command, supported by Beijing across the border. Meeting the EAOs individually is easier for the junta to attend to their separate and unique demands.

However, some EAOs including the Karen National Union (KNU), Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and Chin National Army (CNA), which have engaged in violent clashes with the regime in recent months, have

refused to join the latest round of peace talks. They have said that the negotiations lack inclusion given that the National Unity Government of Myanmar (NUG) and People’s Defence Force (PDF) were not invited. The junta has

denounced the PDF, NUG, and Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH) as terrorist groups and refused to include them in the peace talks. The

recent round of military operations in Karen State in June 2022 could also play a role in dissuading the KNU from reciprocating the peace overtures. The Arakan Army (AA) has also expressed cynicism about the talks given that the Tatmadaw has

waged offensives, occupied religious buildings, and set up military posts in public spaces in Rakhine.

The EAOs adopted divergent reactions to the February 2021 coup, only some expressed willingness in joining forces with the NUG to fight the Tatmadaw while a few ended up switching sides.

Historically, most EAOs have played a minimal role in anti-coup movements given that they have neither had a loyalty to the Tatmadaw nor the National League for Democracy (NLD). Many rebel groups felt that the NLD deprioritised their interests and well-being when they

entered into a power-sharing arrangement with the junta in 2015. Therefore, the EAOs

adopted divergent reactions to the February 2021 coup, only some expressed willingness in joining forces with the NUG to fight the Tatmadaw while a few ended up switching sides. For instance, although the SSA-S

supported the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) following the coup in 2021, it has now changed its position and was the first EAO to accept the junta’s recent ceasefire offer. EAOs will likely continue their strategy of hedging for individual mileage.

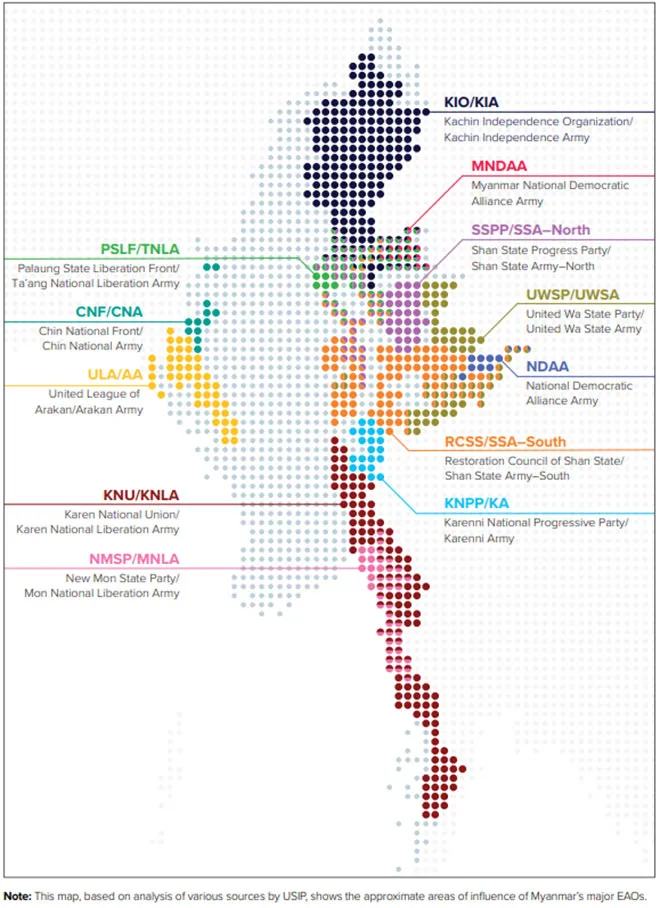

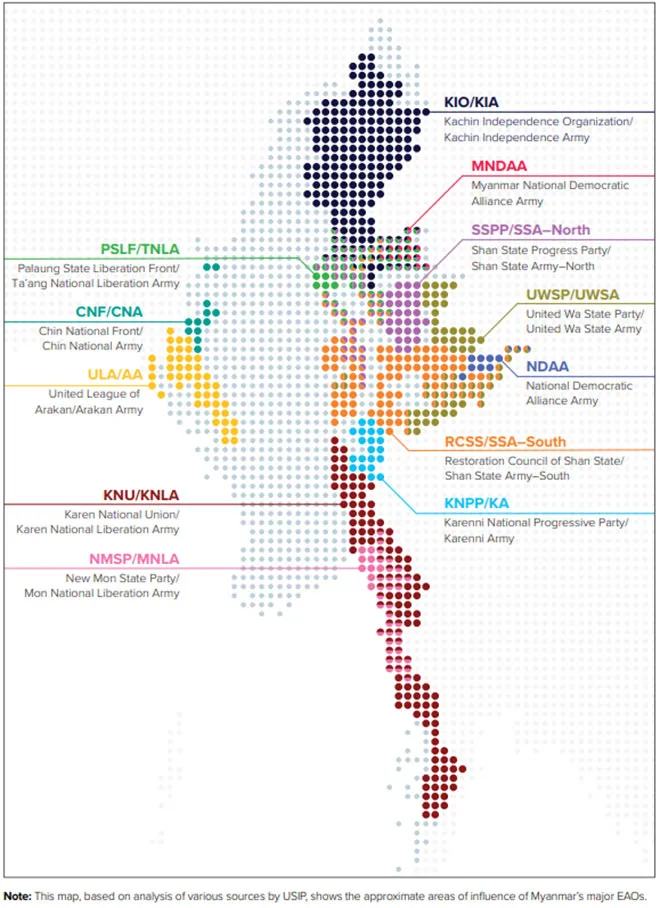

Figure 1: A map of Myanmar showing key areas contested by Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs)

Source: ‘Myanmar Study Group’, p. 23, Final Report, February 2022, United States Institute of Peace (USIP)

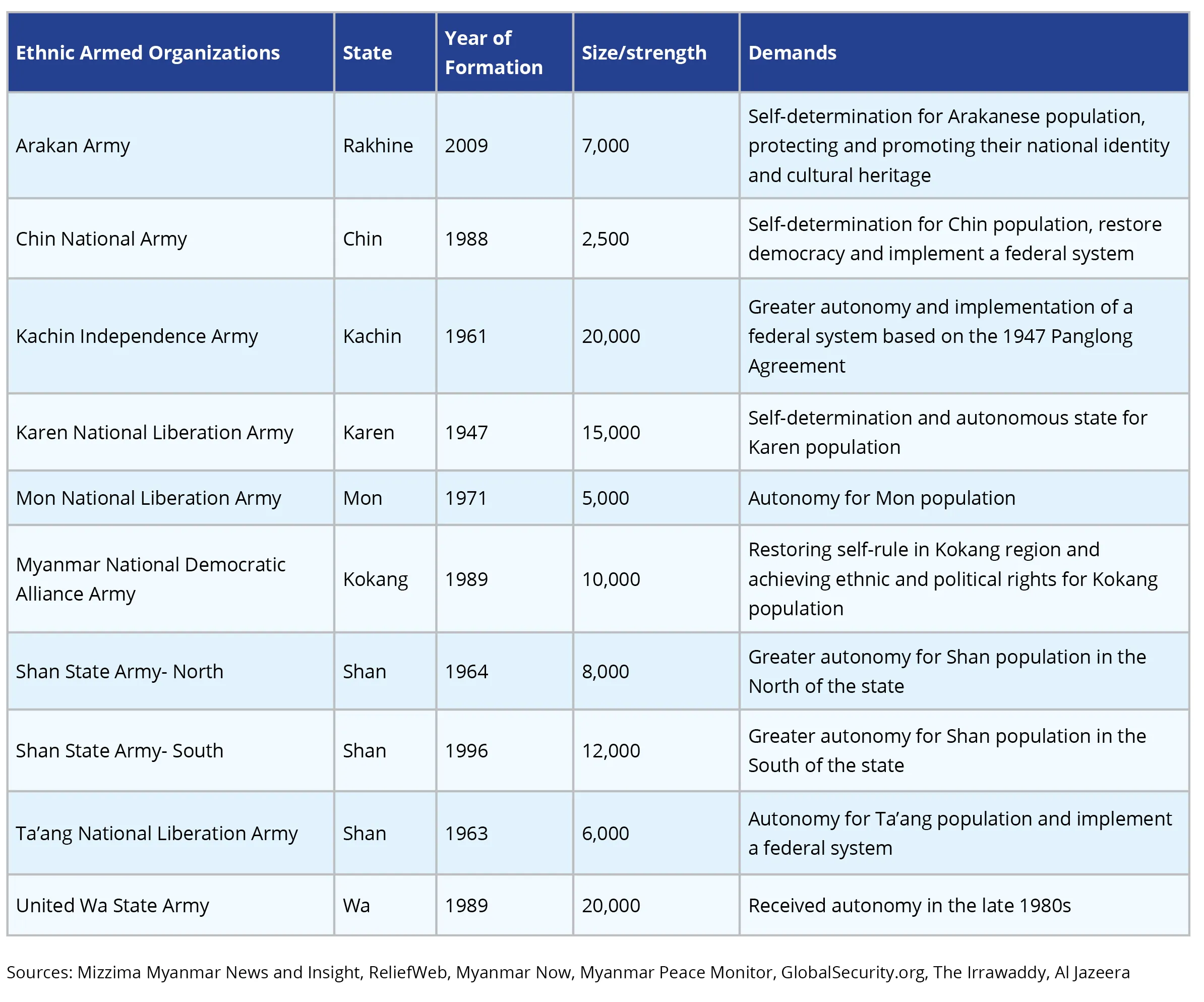

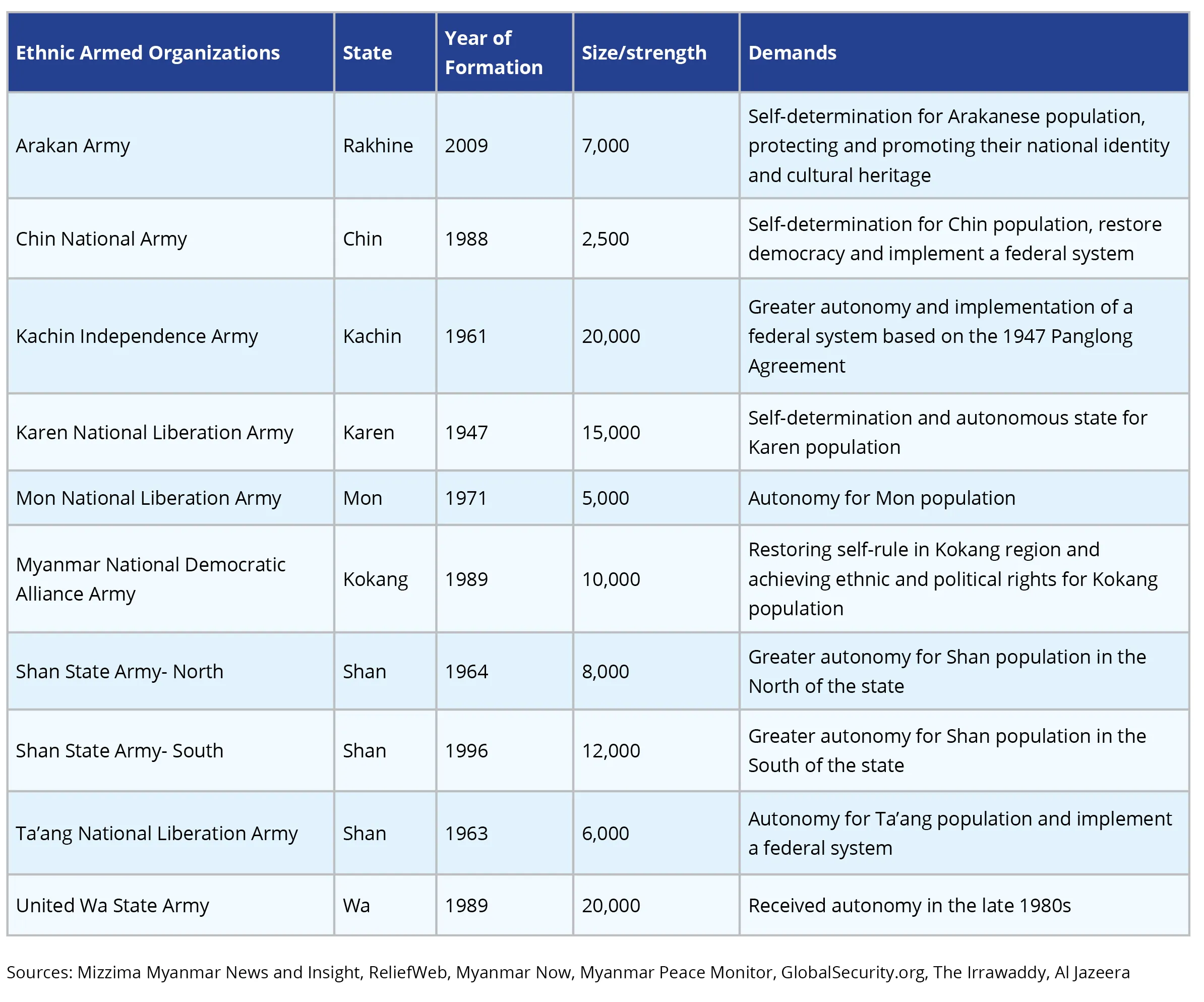

Table 1:

Source: ‘Myanmar Study Group’, p. 23, Final Report, February 2022, United States Institute of Peace (USIP)

Table 1:

Superficial engagement rather than a genuine outreach

The lack of technical details and progress of the peace talks amidst ongoing land and air incursions in the borderlands has

drawn criticism that the negotiations are superficial and hollow. There are three possible reasons for the peace overtures. First, the reconciliation efforts appear to be a smokescreen to conceal the junta’s real intent of continuing their brutal crackdown against those directly and indirectly affiliated with the resistance—from the PDF soldiers to political dissidents to anti-regime netizens. Second, it could be a ruse to

sow discord amongst the groups and find ways to dissuade the EAOs from aligning with the NUG. It could also be a “divide and rule”

policy to delegitimise and instigate conflict given that some of these EAOs

continue to have a factitious relationship with one another. It could also be a distraction to prevent them from aligning with the NUG. Third, the ongoing land and aerial attacks could be a strategy for the junta to come to the negotiating table from a position of power and strength. It may be using its military aggression against rebel fighters and civilians to have an upper hand at these talks.

The negotiations are unlikely to lead to a new and lasting ceasefire agreement given the junta’s tendency of not sticking to its own commitments in the past and the lack of group unity during these peace talks.

Accepting the junta’s offer for peace talks, however, not only legitimises the regime but also serves as a reminder that rebel groups do not have much agency in Centre-peripheral relations. The regime’s vision for nation-building and national unity resulted in processes of discrimination and subordination of minority groups. It remains to be seen what roles would play in the coming years, and whether they will receive more autonomy in the country. After all, the Tatmadaw perceives itself as guardians of the unitary state and strongly opposes efforts toward federalism or equal distribution of power between the Centre and the peripheries. It is also uncertain whether the junta will continue its conciliatory and accommodating stance toward the EAOs once it has consolidated more power across the country. The negotiations are unlikely to lead to a new and lasting ceasefire agreement given the junta’s tendency of not sticking to its own commitments in the past and the

lack of group unity during these peace talks.

The recent developments do not bode well for the NUG which wants EAOs to play ball with them, either through an alliance or by remaining neutral. Efforts by the ousted government to encourage rebel groups to align with them appear to be challenging given the trust deficit between the two sides. Several “peace conferences” in recent years have done little to

overcome the deep resentment and distrust between Bamar and ethnic groups. The KIO’s efforts to

encourage EAOs who do not want to join the peace talks to side with the NUG and PDF have had limited success as well. The lack of positive engagement with the NUG raises the question of how far the ousted government will go to keep its legitimacy intact on the domestic and international levels. At the moment, some Burmese still think that the NUG is their legitimate government and a few western countries continue to engage with them informally. There are also concerns about whether the international community has provided sufficient support to these pro-democracy forces to ensure that Myanmar does not slide into the zone of neglect, indifference, and silence given the disproportionate attention

given to the Ukraine crisis.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

The Tatmadaw’s

The Tatmadaw’s

PREV

PREV