Reserve Bank of India (RBI) announced its October Monetary Policy statement, and tried its best to calm nerves in the market and economy by painting a hopeful picture of recovery. RBI expects the real GDP to decline by 9.5% in 2020-21, “with risks tilted to the downside.”

Policy repo rate and reverse repo rate are kept unchanged at 4.00% and 3.35%, so are marginal standing facility (MSF) and bank rates at 3.35%. Wholesale price index (WPI) in recent months showed slightly upward trend, mainly propelled by a rise in prices of primary articles. So, leaving the rates unchanged was widely expected as the central bank would like to have some flexibility to act in future if the economy turns inflationary. RBI, however, expects the food prices to fall riding on a good kharif production.

Leaving the rates unchanged was widely expected as the central bank would like to have some flexibility to act in future if the economy turns inflationary.

The central bank assured both the market and the government of creating comfortable liquidity conditions so that private and government borrowing are not hampered in any way. Following major liquidity enhancement announcements were made.

- To revive activities in specific sectors with both backward and forward linkages and multiplier effects on growth, the RBI has introduced on-tap targeted long-term repo operations (TLTRO) with tenures of up to three years for a total amount of up to Rs. 1 lakh crore, at a floating rate linked to policy repo rate. Liquidity availed by the banks under this scheme has to be deployed in corporate bonds, commercial papers and non-convertible debentures issued by entities in the growth-oriented sectors.

- The liquidity availed by these TLTROs can also be utilised to extend bank loans to the growth-oriented sectors. The banks which have raised funds under earlier TLTROs will be given option of reversing these transactions before maturity. This is done to ensure smooth and seamless credit operation by the banks.

- Reacting to “feedback from market participants” the central bank also decided to increase the size of special open market operations (OMOs) to Rs 20,000 crore.

- To facilitate liquidity to state development loans (SDLs), the RBI would conduct OMOs in SDLs as a special case during this current financial year. The apex bank expects to facilitate efficient pricing by undertaking these operations.

Though there is no restriction on the maximum period of repo operations, usually these operations are undertaken for a period of one week. Extending the period to three years is intended to enable the banks to extend more loan to the relevant sectors.

The idea that increasing credit supply will facilitate economic revival is doing the rounds for quite some time. The pandemic-induced massive GDP contraction has only accelerated the clamour.

In simple words, the commercial banks earlier used to borrow money from the RBI for a very short period to overcome any immediate liquidity challenges they face. Now, more funds from the RBI would be available to the banks for a much longer period at repo rate. So, low-interest loan (assuming that repo rate will continue to remain at a lower level) will be available for the “growth-oriented” sectors.

For state development loans, however, the cost of borrowing is expected to be higher as those will be raised through open market operations. Now the question that one may ask is — how do all these help in economic revival?

The idea that increasing credit supply will facilitate economic revival is doing the rounds for quite some time. The pandemic-induced massive GDP contraction has only accelerated the clamour. Underlying logic is simple — making low-cost loanable fund available would increase credit offtake, those credits taken (industrial, personal or otherwise) would then be utilised in new economic activities, and finally would result into heightened revival and growth. But, if one looks at the trends in the policy repo rates and credit-deposit ratio in the last one year then a scepticism is bound to emerge.

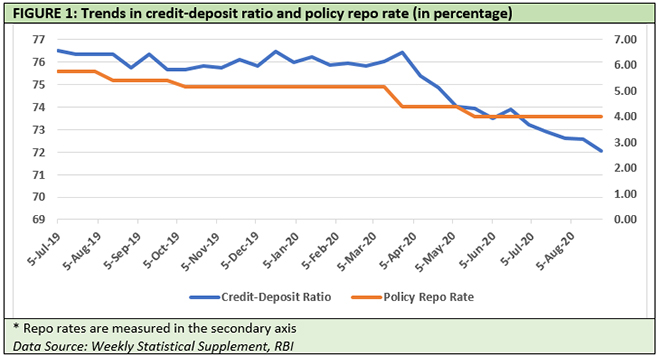

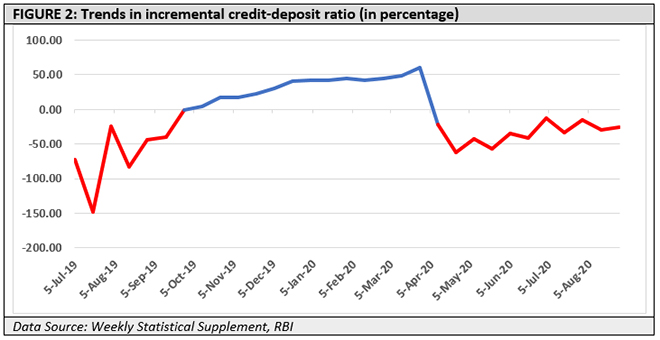

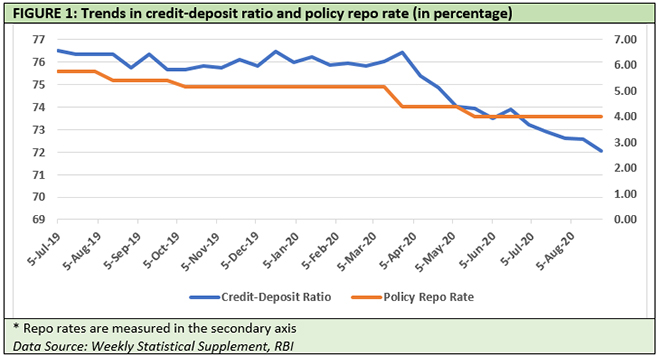

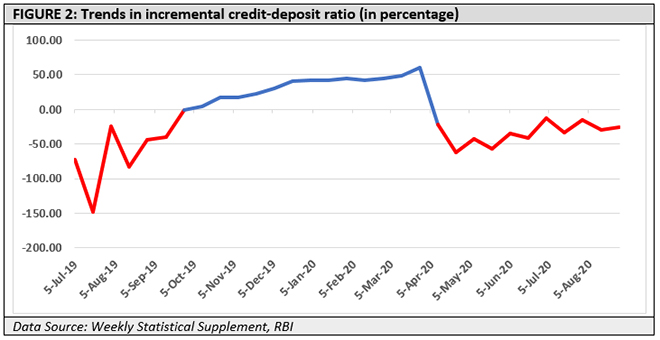

The credit-deposit ratio shows how much of each rupee of deposit is extended as actual credit disbursal. Broadly, this is one of the basic credit growth indicators. Though policy repo rate is continuously falling in the last few years, the credit-deposit ratio has remained constant and since April this year has plummeted during the pandemic (Figure 1). Though the cost of borrowing has consistently fallen down and more credit were made available to the economy, there were very few takers of such loans. The slump in credit demand gets visibly prominent if we look at the trends in incremental credit-deposit ratio. As the name suggests, this ratio shows how much of new deposits are extended as new credit in the economy. This ratio was in the negative territory in the period between July and September last year, it slowly revived to a level of around 60% in March 2020, and slumped thereafter to get into the negative zone once again (Figure 2). To provide a contrast, the value of this ratio was 169.70% on 21 December 2018, 126.29% on 18 January 2019, and 116.01% on 15 March 2019.

The slump in credit demand gets visibly prominent if we look at the trends in incremental credit-deposit ratio. As the name suggests, this ratio shows how much of new deposits are extended as new credit in the economy. This ratio was in the negative territory in the period between July and September last year, it slowly revived to a level of around 60% in March 2020, and slumped thereafter to get into the negative zone once again (Figure 2). To provide a contrast, the value of this ratio was 169.70% on 21 December 2018, 126.29% on 18 January 2019, and 116.01% on 15 March 2019.

Deposit growth rates have been quite steady even during the pandemic, but there was no commensurate growth in credit. Incremental credit-deposit ratio figures only re-affirm that phenomenon. And as can be observed in Figure 2, this trend started much before the pandemic.

Therefore, credit demand is the problem, not credit supply. If there are very few economic actors in the system interested in taking credit and employ those in productive activities, no amount of additional credit supply will be able to solve that problem.

If the malady is entrenched in the demand side, then monetary remedies seldom work out. Fiscal solutions only can take care of the demand-side distortions. The time has come to look for those avenues.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

The slump in credit demand gets visibly prominent if we look at the trends in incremental credit-deposit ratio. As the name suggests, this ratio shows how much of new deposits are extended as new credit in the economy. This ratio was in the negative territory in the period between July and September last year, it slowly revived to a level of around 60% in March 2020, and slumped thereafter to get into the negative zone once again (Figure 2). To provide a contrast, the value of this ratio was 169.70% on 21 December 2018, 126.29% on 18 January 2019, and 116.01% on 15 March 2019.

The slump in credit demand gets visibly prominent if we look at the trends in incremental credit-deposit ratio. As the name suggests, this ratio shows how much of new deposits are extended as new credit in the economy. This ratio was in the negative territory in the period between July and September last year, it slowly revived to a level of around 60% in March 2020, and slumped thereafter to get into the negative zone once again (Figure 2). To provide a contrast, the value of this ratio was 169.70% on 21 December 2018, 126.29% on 18 January 2019, and 116.01% on 15 March 2019. PREV

PREV