Approximately 7 billion of the 9.2 billion tonnes of plastic produced from 1950-2017 has become plastic waste, ending up in landfills or dumped in the

open. Recycling will not help solve the global plastic pollution crisis. Towards ending plastic pollution, the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) 5.2 established an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (

INC) to draft an international legally binding instrument by the end of 2024. The first meeting of the INC was held on 28 November-2 December 2022 in

Uruguay. In the run-up to the meeting, several member states, groups of states, and intergovernmental organisations issued statements of

support; India was not among them.

Indian response to plastic pollution

However, India, taking cognisance of the fact that 3.5 million tonnes of plastic were produced during 2020-21, and that its recycling capacity is only half as

much, decided to discontinue the manufacture, import, stocking, distribution, sale and use of identified single-use plastic (SUP) items that have low utility and high littering potential from 1 July 2022. In any case, recycling will possibly not solve the crisis of plastic pollution. The UNEP Executive Director is of the opinion that “We will not recycle our way out of the plastic pollution crisis: we need a systemic transformation to achieve the transition to a circular

economy.” The laws of thermodynamics, however, come in the way of

dreams of a circular economy. No recycling plant can be run solely off of the excess heat of another recycling plant of similar

capacity.

The UNEP Executive Director is of the opinion that “We will not recycle our way out of the plastic pollution crisis: we need a systemic transformation to achieve the transition to a circular economy.”

To phase out select SUP items by 2022, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC), Government of India notified the Plastic Waste Management Amendment Rules, 2021, on

12 August 2021. The implementation of the ban, however, lies with the respective state governments and their state pollution control boards, therefore, it is not uniform and the states can and do

modify the stringency as they deem fit.

The national ban includes 21 SUP items. These items are categorised under: (i) carry bags that specify minimum thickness in case of polythene bags and minimum weight in case of non-woven bags, (ii) plastic sticks, (iii) packaging/wrapping films, (iv) cutlery items, and (v) other items that include PVC banners, plastic flags, polystyrene for decoration (thermocol), straws, plastic sheet, and pan masala packet.

Implementation of the ban on SUP – Citizen engagement

Five months have passed since the SUP ban came into force but there is little visible impact on the ground. SUP products continue to be available as usual. In the absence of the availability of cheap alternatives to cater the demand of these banned products, and effective public engagement and concerted action by end consumers (refusal to use), the effectiveness of the ban will remain elusive.

To enforce the ban through citizen action, the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) has launched an

app (SUP-CPCB) urging citizens to act as watchdogs and help authorities to take appropriate action against violators. Through the app, citizens can report SUPs being manufactured in industry, used in restaurants, sold in shops, stored and distributed by the supplier. As a mechanism to curb the use of SUP, the app could be very effective in soliciting citizen action since no state machinery by itself will be able to achieve universal implementation of the ban on SUP.

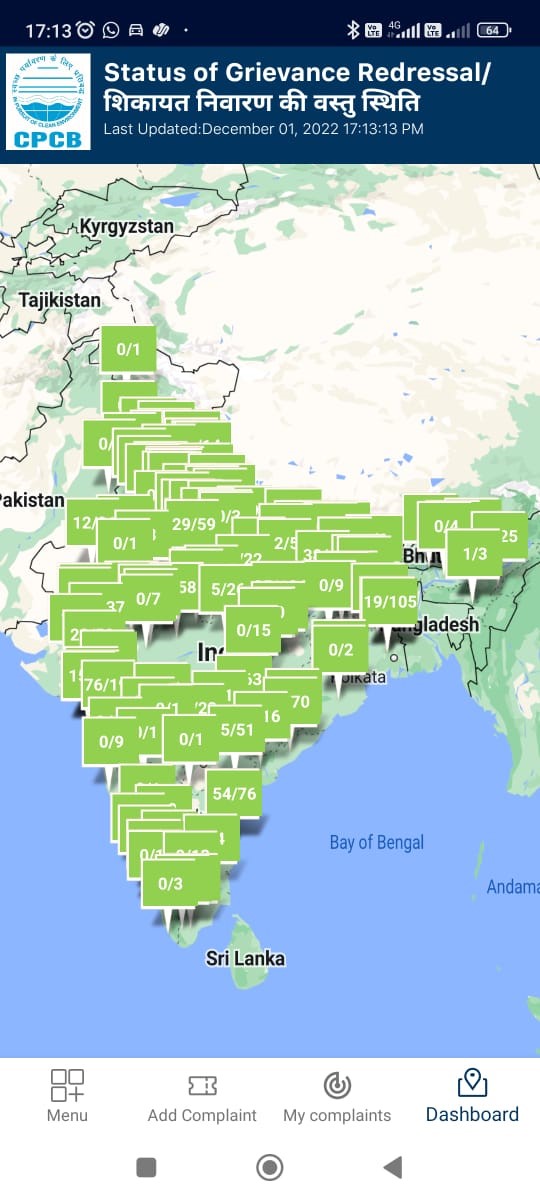

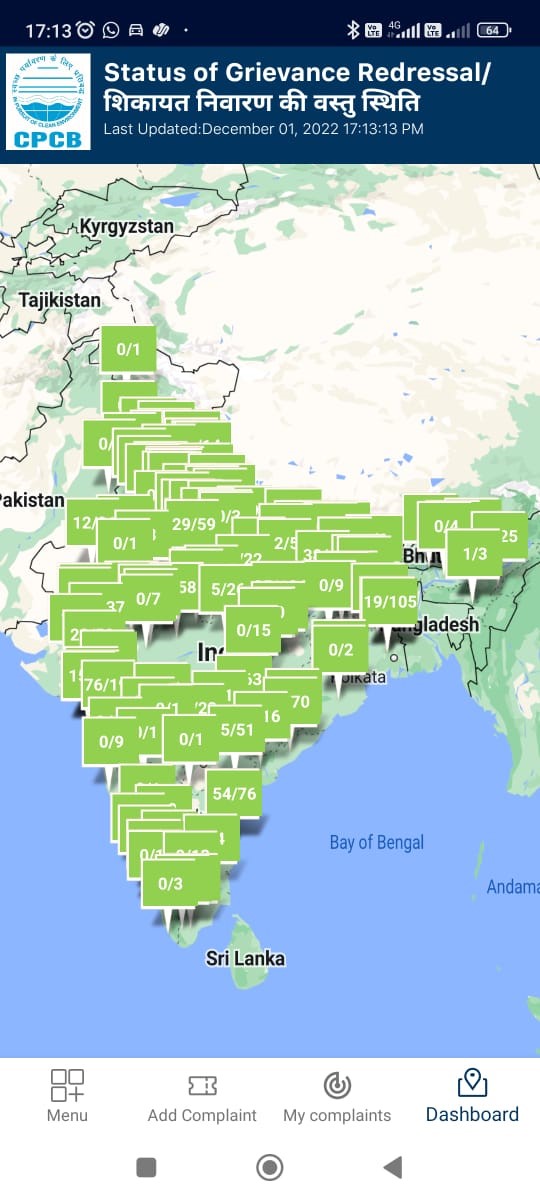

The denominator is the number of complaints in each of the five categories and the numerator is possibly the number of cases where action has been initiated or taken.

Screenshot of the app’s dashboard

Screenshot of the app’s dashboard

However, awareness of the app is very low, since August 2022, the Android version of the app has been downloaded only about 5,000 times, and the app is not user-friendly (3.2 rating on a scale of 5 based on 55 reviews), and asks for login credentials to access complaints which may fail to protect the complainant’s anonymity. While lodging complaints, the app asks for personal details like name, mobile number and email id but it is still possible to lodge a complaint without furnishing personal details. Accessing information without login is a challenge.

The app dashboard provides an overview of the complaints lodged by location across the country. The denominator is the number of complaints in each of the five categories and the numerator is possibly the number of cases where action has been initiated or taken. There is no way to ascertain from the app the nature of action taken, and the outcome. It could only be as much as assigning the case to the concerned official of the state Pollution Control Board.

Scope for improvement

To tackle plastic pollution, one of the approaches should be to discontinue the manufacture and use of identified SUP rather than penalise the offender. The ban and subsequent penalties might put small and micro enterprises out business but large corporate entities may be able to bear the penalty for manufacture and use of SUP, and yet be profitable. This would turn the polluter pays principle on its head, a polluter pays to be able pollute. For example, cigarette packs with manufacturing date in September and thereafter are still being sold with plastic film wrapping. In the absence of alternative products with similar characteristics and at similar price points, instances of SUP use will continue.

The ban and subsequent penalties might put small and micro enterprises out business but large corporate entities may be able to bear the penalty for manufacture and use of SUP, and yet be profitable.

The press release of the

MoEFCC on 28 June 2022 mentioned capacity building workshops for micro, small and medium enterprises (MSME) units to provide them with technical assistance for manufacturing of alternatives to banned single use plastic items with the involvement of CPCB/SPCBs/PCCs along with Ministry of Small Micro and Medium Enterprises (MSMME) and Central Institute of Petrochemicals Engineering (CIPET) and their state centres. Apparently, provisions have also been made to support such enterprises in transitioning away from banned single-use plastics. However, no information is available in the public domain from CPCB/SPCBs, MSMME and CIPET regarding either technical assistance or of any financial assistance for developing alternatives to banned single-use plastics. These should have preceded the ban; correct sequencing of smaller actions ensures success or failure of a composite action and desired outcome. In the case under discussion, the ban is in place, as is the app, and conscious citizens are registering complaints all over the country despite the app being not user friendly, yet SUPs are as omnipresent as they were. It might be prudent to keep the SUP ban in abeyance for a specific period, revisit the sequence of actions to get it right, and reintroduce the ban. Ultimately, it is the discontinuation of SUP that is of significance rather than policing and penalising the offender.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Approximately 7 billion of the 9.2 billion tonnes of plastic produced from 1950-2017 has become plastic waste, ending up in landfills or dumped in the

Approximately 7 billion of the 9.2 billion tonnes of plastic produced from 1950-2017 has become plastic waste, ending up in landfills or dumped in the

PREV

PREV