With the economy in a state of lockdown, the rivers had come back to life. There has been a remarkable improvement in the water quality in various stretches of rivers which previously painted a dystopian picture of grey and froth. They appear clean and healthy and it is a sharp contrast to what the status quo had been so far — a sign of hopelessness and failure despite millions of Rupees being pumped into numerous action plans under successive governments to clean our rivers. The National Green Tribunal (NGT) had also taken note of the situation by directing the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) to study and analyse the extent of reduction of pollutants in the Ganga and Yamuna and the reasons for such an occurrence. Moreover, it has also instructed that full compliance of law should be ensured once the economy reopens and the economic and cultural activities resume. As Unlock 1.0 is currently underway and economic activities have resumed in a limited capacity, it is worthwhile to ponder if simply expecting compliance is of any help when history tells us that compliance is contingent upon the effective functioning of certain regulatory mechanisms which have remained weak. In that case, what can be an alternative mechanism? What if rivers are regarded as legal entities? Can this new legal paradigm help to ensure their protection and preservation?

Source: Down To Earth

Source: Down To Earth

Rights-based approach

Bizzare as it may sound, the growing awareness around granting a legal ‘personhood’ to rivers is part of a global movement that has drawn its inspiration from indigenous views of nature — of acknowledging the interdependence on nature and considering it sacred. It all started with the passing of legislation in the parliament of New Zealand in 2017 that recognised the country’s third-longest river, the Whanganui river, as a legal person with the same set of rights as citizens of the country would have for themselves. This was seen as the amalgamation of Western legal values with the Maori worldview for the protection of a river that the Maoris consider to be their living ancestor. This legislation allowed the river to be represented in the court of law as a litigant with community representatives acting as its legal administrator.

It all started with the passing of legislation in the parliament of New Zealand in 2017 that recognised the country’s third-longest river, the Whanganui river, as a legal person with the same set of rights as citizens of the country would have for themselves.

This was followed by similar judgements and observations in different parts of the world like Colombia, Australia, United States of America etc. Closer home, the Uttarakhand High Court (UHC) was quick to follow the legal developments in New Zealand with a ruling through its parens patriae jurisdiction that the Ganga and Yamuna, their tributaries, and the glaciers, springs and various catchment features feeding these rivers and ensuring the sustenance of flow in Uttarakhand, have rights as a “juristic/legal person/living entity.” The court also made it explicit that these rights were akin to fundamental rights and any injury or harm caused to these bodies shall be the same as harming a person. However, this order was stayed by the Supreme Court of India soon after. A plea was made to the apex court by the Uttarakhand Government citing the legal and administrative complexities that would emerge from the UHC order. Reasons cited include the assertion that regulation of interstate rivers is guided by the centre and a single state cannot be held responsible for it. Similarly, it was questioned that if the river becomes a legal entity, then can the victims of floods file suit against the Chief Secretary of the State (who had been entrusted with the custodianship of the rivers by the UHC) and whether the State Government would be liable to bear the financial burden of the settlement.

These point out the lack of clarity and the consequent uncertainty that prevails regarding the complete range of outcomes, implications and repercussions of recognising rivers as legal entities. However, considering that the belief system which is giving way to such jurisprudence as already intrinsic to this land, it is only a matter of time before such a movement were to become the mainstay of environmentalism in India for protecting natural features like rivers. Globally, as well, the acceptance of this environmental jurisprudence is on the rise as the human society emerges from a pandemic — something that is often get caused by the modifications done to natural landscapes.

New possibilities

Differing from the present legal paradigm of treating the rivers as passive objects that require protection and thereby placing a limit on the action of humans, the new paradigm promises to empower rivers (through their legal guardians) in a way that they can actively participate in litigations for protecting themselves. This could also mark a change in the way environmental laws and guidelines have been interpreted so far — essentially from a human perspective. The new paradigm could involve interpreting the rights of the river where humans are at the periphery and the regulatory mechanisms are designed by keeping the river’s interest at the core.

The new paradigm promises to empower rivers (through their legal guardians) in a way that they can actively participate in litigations to protect themselves. This could also mark a change in the way environmental laws and guidelines have been interpreted so far.

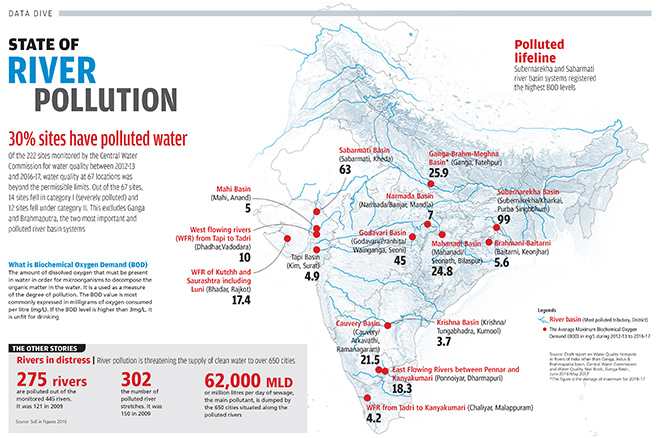

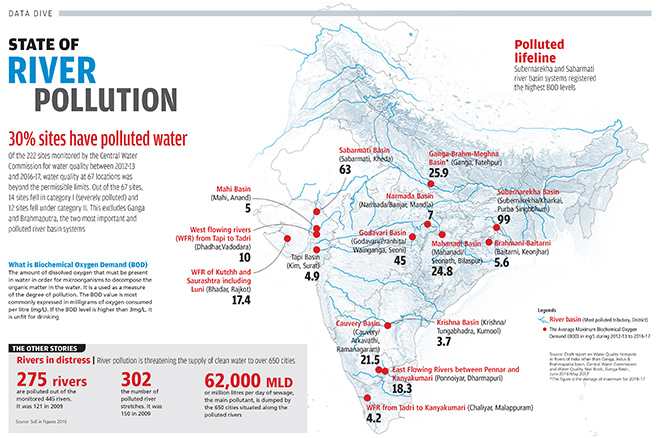

This can lead to profound and wide-ranging consequences such as redefining the quantum of environmental flows in rivers as mandated by law, changing the acceptable limits of biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) in the rivers, reassessing the ‘beautification’ of riverfronts and their development etc. So far, these have been initiated or formulated by considering the human interest or what humans have regarded as important for the river and its ecosystem. However, it must be noted that human activities that draw from the river and have coexisted with it like fishing, agriculture etc. can continue as long as such activities do not negatively impact the health of the river or cause irreversible damage to it. Observers have argued that the new paradigm would enable a constructive and healthy relationship with rivers and help to maintain its flow, its floral and faunal diversity, its catchment and various other elements of the riverine landscape in a manner which is in harmony with broad human interests.

Need for caution

Despite the incredible and limitless possibilities, there are umpteen reasons to be cautious for an impetuous advancement. Firstly, the idea of parenthood/custodianship appears quite ambiguous. While in the case of Whanganui river, the parenthood is shared equally by the indigenous Iwi people, who have a long history of a struggle to safeguard the rights of the river, and the New Zealand government, the UHC order offers little confidence. The parenthood of Ganga and Yamuna was conferred to a bunch of nodal officers of the NAMAMI Gange project along with two non-officials with a legal background. The legal custodian is the most important functionary and choosing an inappropriate guardian for a river could simply make the whole exercise a self-defeating one.

Similarly, recognising rivers as legal entities could turn out to be counterproductive if there is a fundamental shift in the community’s attitude towards conservation and reduces their willingness to act out of an underlying belief that the river is capable to protect itself. Another caution would be to not reduce the entire exercise to juxtaposing rivers in place of humans in the eyes of the law and arguing for rights of the river akin to human rights. Rather, the emphasis should be in recognising a river as a legal personality and reshaping the law so that it is centred on the needs of the river. Moreover, due to a lack of an independent and interdisciplinary River Basin Authority in India which is built on the tenets of an Integrated Water Systems Governance, there remains the ‘interstate hurdle’ of implementing river rejuvenation and conservation plans. On the flip side of things, assigning the status of a legal entity could also necessitate the union government to build a cooperative mechanism amongst the states and create institutions which can act as a custodian for the river — typically a river basin authority. Under Article 262 of the Indian Constitution, the Union Government is well within its rights to undertake such a move.

Choosing an inappropriate guardian for a river could simply make the whole exercise a self-defeating one.

Therefore, the scope of the emerging environmental jurisprudence of assigning legal rights to rivers extends well beyond the objective of merely cleaning our rivers. It could usher in an entirely new discourse and fundamentally change the ways we interact with our rivers. However, one also needs to be mindful of the lack of scholarship to complement the march onto this uncharted territory, a reflection of which can be found in the section above. Most importantly, new institutions will have to be created and a strong regulatory mechanism will have to be put in place if we aspire to go the Whanganui way in the post-COVID era.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source:

Source:  PREV

PREV