The French government recently banned the extreme right-wing and anti-immigration group “Gènèration Identitaire” (Generation Identity) by a government decree since it

promoted “discrimination, hate, and violence” and took the form of a private militia. A day later, Germany’s domestic intelligence agency, the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz), placed the Alternative for Germany (AfD) — Germany’s largest opposition party — under surveillance for posing a

threat to democracy and supposedly having ties to right-wing extremism. However, the Cologne court suspended the surveillance orders immediately to prevent “

unjustifiable interference” with equal opportunities of political parties.

This recent censuring is, unfortunately, too little, too late.

The two aforementioned groups are primarily united by their staunch opposition to mass immigration and the cultural liberalisation of Europe. Even though their highly

provocative rhetoric and

xenophobic ideals are antithetical to the European Union’s motto of

“Unity in Diversity” and must be checked

, this recent censuring is, unfortunately, too little, too late. While Generation Identity could be categorised as a fringe group, AfD has slipped into the

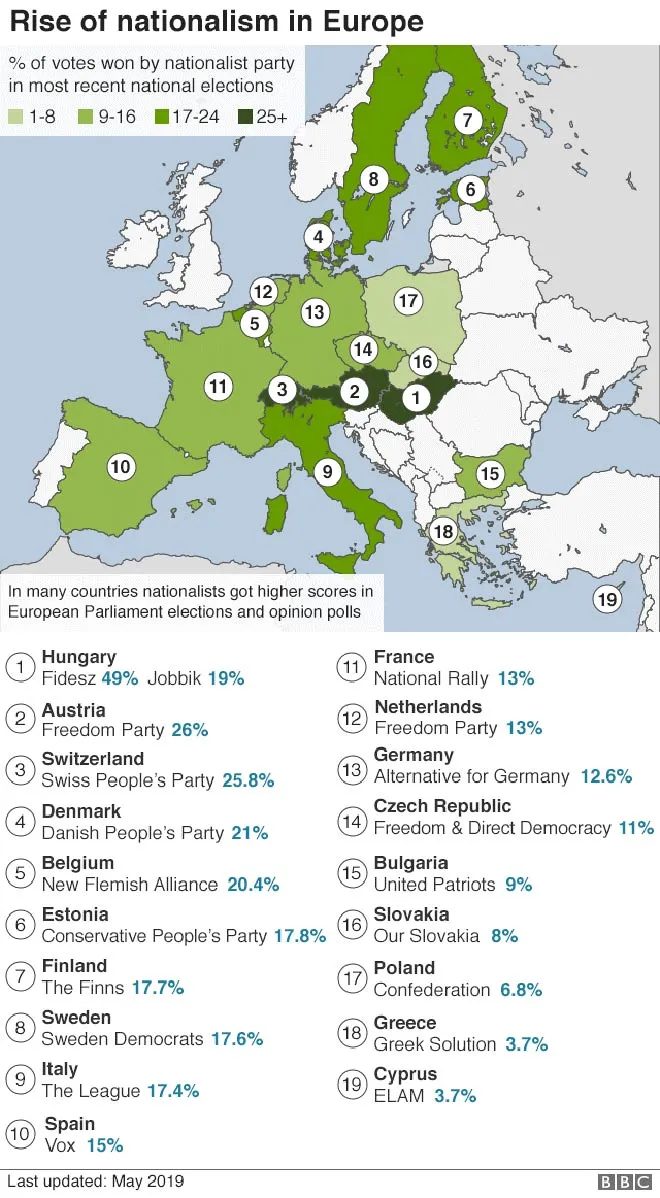

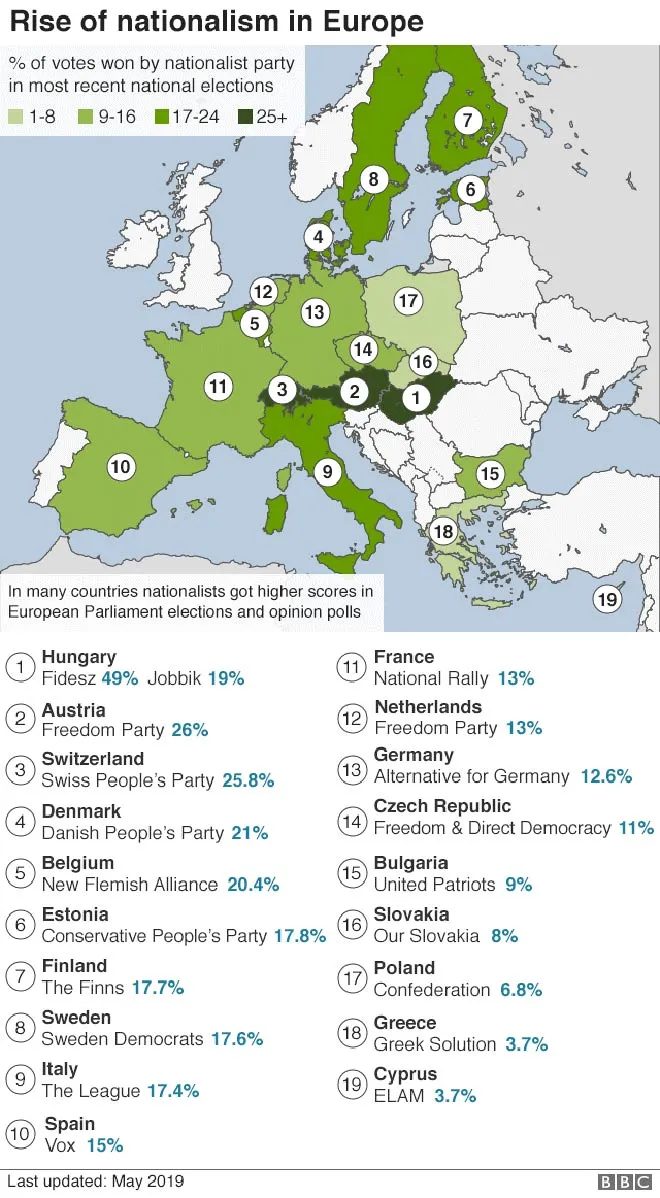

mainstream in recent years. Concerningly, akin to the AfD, right-wing populists are no longer on the periphery of European politics. They have instead become the norm. Although it would be reductive to attribute this surge in populism solely to the inflow of immigrants, it has indisputably been a decisive factor because far-right parties across Europe have recently been winning elections by unexpected margins. Unsurprisingly, these parties have been focusing their campaigns

majorly on “anti-immigration.” Additionally, recurrent electoral defeats have been driving Europe’s centre-left parties to change long-held stances on migration. With even Europe’s left turning right on immigration, and far-right ideologies gradually getting entrenched in the mainstream, the anti-immigration sentiment is here to stay. The prospects for urgently required reforms to Europe’s

inadequate and rights-abusing policies on refugees also look bleak because of the lack of leadership to push for them.

In what was the biggest wave of refugees since World War II, over a million immigrants made life-threatening journeys across the Mediterranean to reach Europe in 2015. These were mostly people trying to flee persecution in various Middle Eastern and North African states that have been embroiled in protracted conflicts for quite some time. Despite being the world’s wealthiest and the most integrated bloc, the EU severely struggled to manage the inflow

efficiently. Resultantly, the European voters have transformed a series of recent elections into popular referenda on immigration and the people’s preferences are reasonably clear — most of them want the immigrants out.

With even Europe’s left turning right on immigration, and far-right ideologies gradually getting entrenched in the mainstream, the anti-immigration sentiment is here to stay.

Large-scale immigration has

raised security and cultural concerns,

as well as fears of economic displacement among Europeans. Capitalising heavily on this widely prevalent anti-immigration, anti-internationalist sentiment, far-right parties across Europe have managed to shift the political balance in Europe by scoring unprecedented victories across Parliaments. By October 2017, roughly two years since the refugee crisis, 24 European countries had

right-wing nationalist members of parliaments. In the French Presidential Elections of May 2017, far-right Presidential Candidate Marine Le Pen secured

34 percent of the votes, making it the Front National’s best ever electoral result. The anti-immigration Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ), secured 26 percent (up from 20.5 percent in the previous elections) of the votes in the October 2017 elections and joined the governing coalition. In the Czech Republic, Miloš Zeman, a fierce opponent of immigration, secured the majority vote

(52 percent) to beat his opponent and ensure his second five-year term in office. The 2017 elections in Bulgaria witnessed the inclusion of a far-right party in the form of the Volya movement that won seats (12) for the first-time ever. Viktor Orbán, the Hungarian leader of the far-right populist Fidesz party, won his

third consecutive term in 2018. Campaigning on a ‘Slovenia First’ platform (simulating Trump’s ‘America First’), Janez Janša’s right-wing opposition won 25 percent of the votes and formed the government. Even in Sweden, one of the most liberal countries in Europe, the far-right

Sweden Democrats that rose from the white supremacist and neo-Nazi fringe, massively bolstered their vote share by securing 17.6 percent of the votes in 2018 and becoming the third-largest party in Sweden’s Parliament.

Source: BBC

Source: BBC

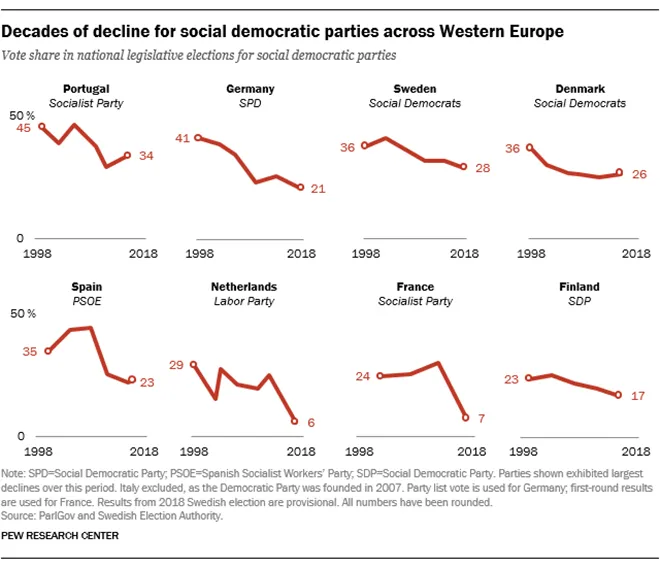

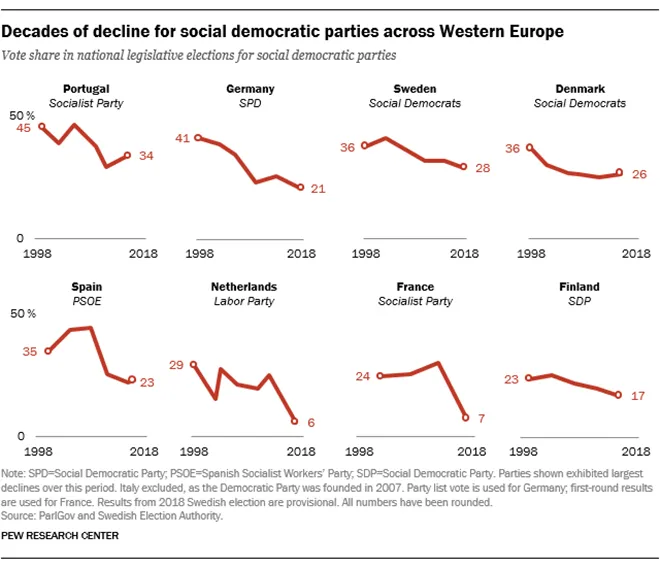

To keep the far-right in check over immigration-related rhetoric and policies, Europe requires alternative leadership, deeply committed to liberal ideals. This has traditionally been embodied by Europe’s centre-left, the social democratic parties. However, the far-right’s skillful garnering of votes has resulted in shocking electoral outcomes for the social democrats. The Socialists in France, spearheaded by Benoît Hamon won only 6.2% percent of the votes in 2017, in contrast to the popularity wave that they rode just 5 years ago. In the Netherlands, the Labour Party’s vote share fell to just 5.7% percent from 25 percent in 2012. Similarly, the German Social Democratic Party fell to a score of

20.5 percent in the September polls, marking its worst since the Second World War. Despite having won 33 percent of the votes as recently as in 2006, the Czech Social Democrats finished with only 7 percent of the votes in 2017.

Source: Pew Research Center

Source: Pew Research Center

These electoral results abundantly echo the growing anti-immigration sentiment across Europe. Consequently, driven by electoral interests, social democrats have taken unexpected stances on immigration. In Germany, Andrea Nahles, who was elected the first female leader of the Social Democrats,

triggered an unexpected conversation within the coalition government by saying that Germany “cannot accept all.” This was in stark contrast to the SPD’s established aims for a European solution and the rejection of sealing borders. Denmark’s social democrats, led by Mette Fredriksen, took a hardline stance on immigration, and

won elections in 2019. Just two months after he said: “My Europe doesn’t build walls, my Europe takes refugees,” Sweden’s Prime Minister, Stefan Löfven (of the Swedish Social Democratic Party) called Sweden’s traditionally open immigration policy

unsustainable. Additionally, under pressure, even the centre-right has been seen swaying towards radical rhetoric in recent years. In an open

letter, Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte, took a blatant dig at immigrants, stating that “people who refuse to adapt and criticise our values should behave normally or go away”; this leaves minimal choice for pro-immigration voters in Europe.

Driven by electoral interests, social democrats have taken unexpected stances on immigration.

The policy landscape on immigration in Europe has been quite grave and requires substantial reforms. Ever since the refugee crisis began, instead of providing safe and orderly channels into the EU for asylum seekers and refugees, EU member states have

endorsed policies that limit arrivals and

controversially outsource responsibility to unstable regions outside the EU like

Turkey. The EU’s response has had tremendous

human costs as well. The emphasis on stemming arrivals instead of developing safer, legal alternatives to reach Europe has led to underground smuggling networks that use unsafe routes to smuggle immigrants, putting their lives at

risk. Successive EU presidencies have also tried to reform the

contentious Dublin regulations due to its unfair nature but have failed because of the lack of solidarity between member states. Given that the most commonly used criterion is that of the ‘first country of asylum,’ the responsibility to accept refugees falls disproportionately on border countries like Greece and Spain. The member countries’ refusal to share responsibility has further resulted in growing frustration in Greece, which has ultimately led to human rights

abuses against immigrants. Similarly, Spain, which many believed was immune to the far-right because of its past under dictator Franco, has witnessed the rise of the populist

Vox party. Vox became the third-largest party in the Spanish Parliament by securing 52 seats in the 2019 elections. The party raised its profile in the aftermath of an increasing number of migrants arriving from Africa, as it campaigned for tougher controls on immigration.

Given that the most commonly used criterion is that of the ‘first country of asylum,’ the responsibility to accept refugees falls disproportionately on border countries like Greece and Spain.

Instead of reformation, the populist wave that has blanketed Europe could only be expected to worsen the pre-existing scenario. With many more far-right leaders being elected into European Parliaments and even the centre-left slowly but surely turning anti-immigration as a counter, we may witness a growing solidarity on policy decisions unlike earlier. However, this solidarity is likely to be showcased on policies to keep immigrants out instead of adequately handling the crisis based on human rights principles.

Banning of Generation Identity and surveillance of the AfD, although important, seems to be contributing only modestly to resolving a much deeper problem that exists in Europe. To effectively clamp down on discriminatory and xenophobic rhetoric and policies, European leaders must deeply embrace the principles of inclusion and peaceful coexistence. However, gauging from the current scenario, the future looks uncertain for refugees in Europe.

The author is a research intern with ORF.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

The French government recently banned the extreme right-wing and anti-immigration group “Gènèration Identitaire” (Generation Identity) by a government decree since it

The French government recently banned the extreme right-wing and anti-immigration group “Gènèration Identitaire” (Generation Identity) by a government decree since it  Source:

Source:  Source:

Source:  PREV

PREV