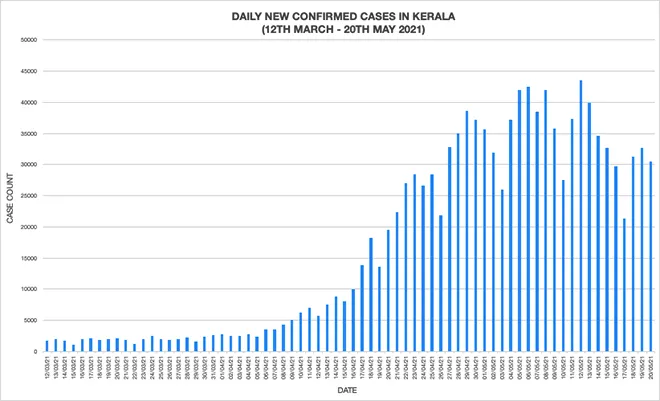

When COVID-19 engulfed India in 2020, Kerala garnered significant praise for its management of the pandemic. Under erstwhile Health Minister KK Shailaja’s leadership, Kerala ensured that its healthcare systems were not overwhelmed, as occurred in several states. Well-coordinated efforts from local governments, volunteers, and civil society groups also aided the government in combating COVID-19. While Kerala was amongst the states with the highest number of cases, it kept the official case fatality rate below 0.5 percent for the initial months.

However, in recent months, the narrative has dramatically been reversed. Kerala’s daily new case count has surpassed that of many of the worst affected states. While the latter have been able to significantly reduce their caseload since the second wave hit, on 25 August, Kerala logged its highest number of infections (30,491) in a single day. The state is averaging over 19,000 confirmed cases per day over the last three weeks.

Yet, curiously, the fourth nationwide serosurvey conducted by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) shows that only 44.4 percent of the individuals in Kerala have been exposed to the virus. This is the lowest in the nation, demonstrating the success of the state’s initial efforts. However, this is still a cause for concern since the remainder of the state’s population has not developed the levels of herd immunity that could minimise the effects of another surge in cases.

While Kerala was amongst the states with the highest number of cases, it kept the official case fatality rate below 0.5 percent for the initial months.

Looking back, it is intriguing that Kerala performed so well in the early months of the pandemic, given the numerous factors that made it susceptible to devastation. This article presents an overview of Kerala’s unique response to pandemic management and examines it from the lens of its pre-existing politics and mode of governance. It also seeks to understand why exactly these mechanisms fell short in the second wave.

Why did Kerala initially stand out?

Kerala aimed to minimise fatalities. Thus, those experiencing symptoms of infection were closely monitored by health personnel and administered the appropriate medical care. Combined with its strong public health system, Kerala’s efficient ambulance services took patients to oxygen-providing facilities only if they were experiencing life-threatening symptoms.

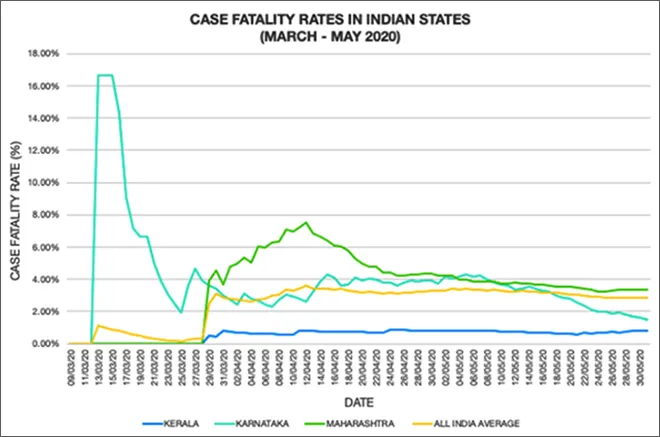

Figure 1 below compares Kerala’s case fatality rate with that of other states during the first few months of the pandemic:

Figure 1; Source: api.covid19india.org

Figure 1; Source: api.covid19india.org

Further, Kerala had previous experience of dealing with natural disasters and health emergencies particularly the highly contagious Nipah virus. The surveillance systems it put in place to contain the spread of Nipah through contract tracing and isolation enabled it to be better prepared for the next disaster. Kerala was also well served by its legacy of social democracy.

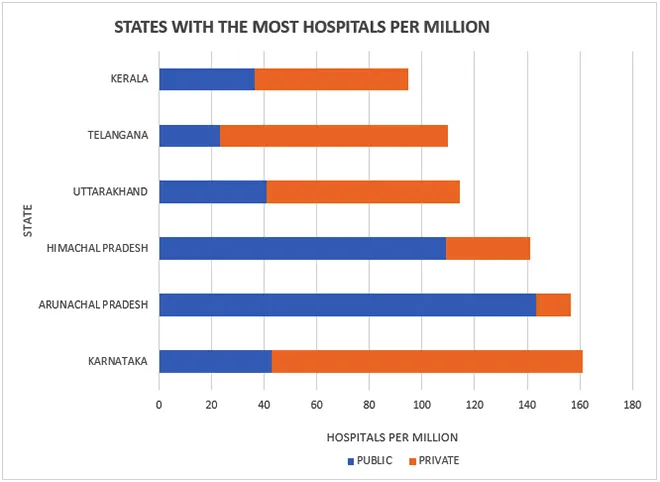

Kerala’s health Infrastructure

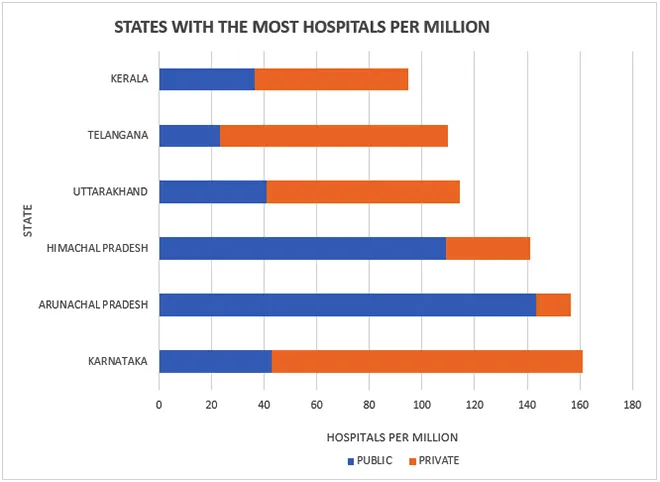

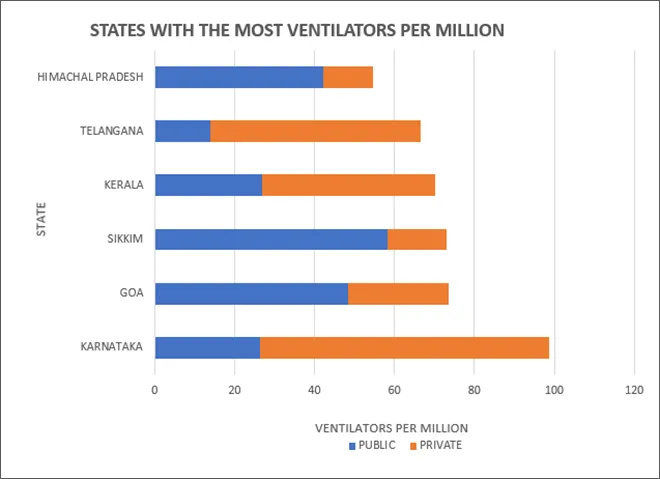

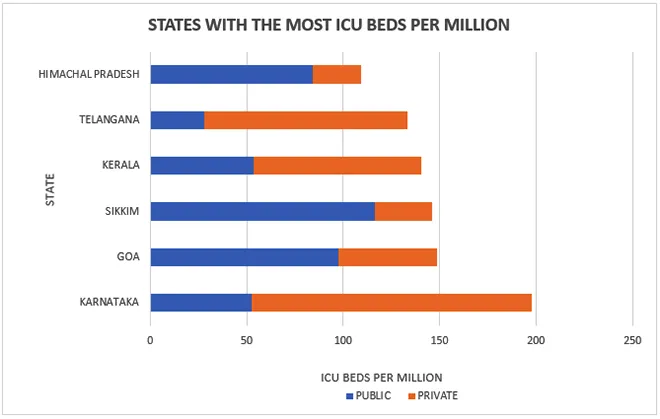

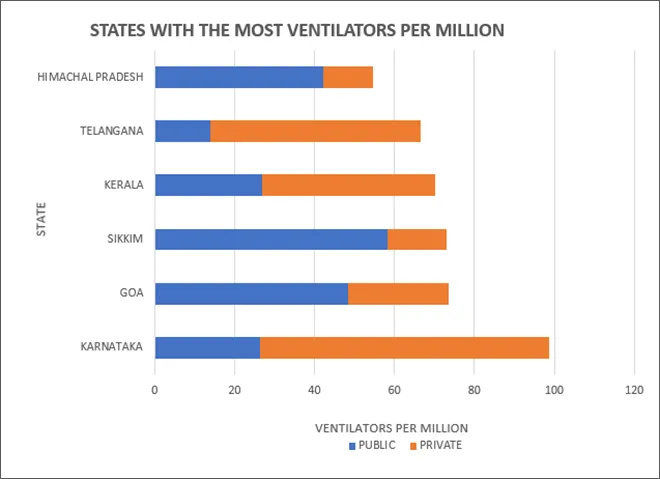

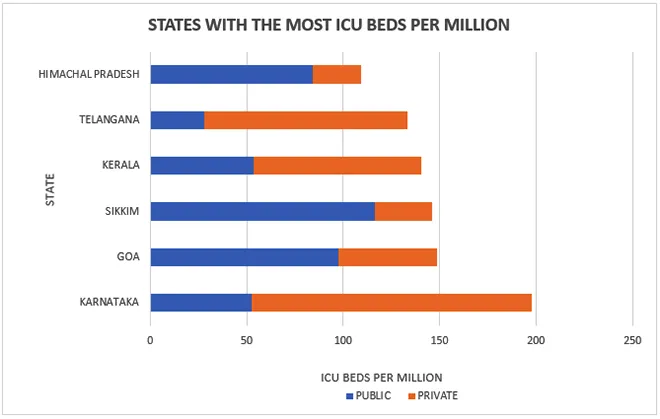

Kerala is one of the states with the best health infrastructure in the country. The following three visualisations compare Kerala’s health infrastructure with that of the five other states with the highest number of hospitals, ICU beds, and ventilators per million.

Figure 2.1; Source: decovindia.com

Figure 2.1; Source: decovindia.com

Figure 2.2; Source: decovindia.com

Figure 2.2; Source: decovindia.com

Figure 2.3; Source: decovindia.com

Figure 2.3; Source: decovindia.com

Social democracy aiding the pandemic response

What has helped Kerala to better endure in gathering responses to the pandemic is its strong social democracy. Social democracies prioritise welfare measures that benefit the whole citizenry. The origins of social democracy in Kerala can be traced back to the erstwhile Kingdom of Travancore, whose rulers started primary educational institutions for children of all backgrounds in the 19th century. In the following decades, they have invested in vaccines against diseases such as cholera and smallpox, which had disproportionately affected backward caste individuals.

Looking back, it is intriguing that Kerala performed so well in the early months of the pandemic, given the numerous factors that made it susceptible to devastation.

According to research scholar Prerna Singh, Kerala’s political elites developed a single Malayali identity and competed to ensure good service delivery without discriminating amongst different sections of society. After Kerala attained statehood in 1956, early Communist governments continued the emphasis on education and healthcare for all citizens. The first Chief Minister, EMS. Namboodiripad, defined the Communist Party as the “national party” of Kerala which sought to fulfill the “Development-defined ideal vision of a unified Malayalee people”. Over the following decades they gave legitimacy to popular movements and groups working to improve public welfare. What emerged was a population viewed by the government as “rights bearing citizens”. High standards of public welfare and the competitive electoral system in the state ensured that Congress governments also continued the efforts of the Communists to remain popular amongst voters.

It is creditable that Kerala defied efforts to craft identity on the grounds of religion, given that it has the second largest proportion of minorities in India after Punjab. The sense of solidarity that emerged at the regional level helped to create a robust and inclusive healthcare system which continues to serve the state well. Unlike elsewhere in India where minorities were scapegoated and migrants callously ignored, Kerala Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan declared that “a virus has no religion” and implemented measures to take care of all Kerala residents, including migrants.

Role of local government

Kerala’s local governments also played a crucial role in responding to the pandemic. Initially they assisted with the “Break the Chain” campaign, by educating the public on the dangers of the coronavirus and ways to prevent its spread. As early as February 1st, 24/7 control rooms were established at the district level to monitor hospital bed capacity, as well as oxygen supply and demand. Local government bodies also ensured that those in need received adequate food and medical treatment, and delivered the same to doorsteps when it was necessary.

Local governments have received a significant share of the state’s annual budget, leading to greater autonomy regarding matters of healthcare. These funds helped districts improve the quality of care at primary health centres catering to their respective population’s needs. By continuing to take these measures in line with Mission Aardram, local bodies are trying to incentivise families to utilise public health services over costlier private healthcare.

Resilient and strong civil society groups

Apart from the health measures to fight the pandemic, the state government has also helped its people cope with this crisis in a number of ways. While migrant workers in other parts of the country were facing various hardships, free shelter was provided to those stranded in Kerala. Kudumbashree women’s empowerment groups worked with local governments to set up community kitchens near these shelters to ensure that the migrants would not go hungry. The government also announced an INR 20,000 crore relief package to benefit those below and above the poverty line. The holistic response to the coronavirus and to other crises during the Pinarayi Vijayan government’s first term has had some role in the Left Democratic Front’s back-to-back electoral victory.

Exposing vulnerabilities

Kerala is India’s third most densely populated state and sees high mobility across its borders nationally and internationally. These factors began to catch up with the state during the second wave, especially after the Delta variant started to spread in India. Initially, the Kerala government was prepared for a surge in cases, having invested in oxygen plants to ensure that there would be adequate oxygen supplies. The excess supply enabled Kerala to export oxygen to other states such as Goa, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu, which were experiencing shortages.

The Kerala experience in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic illustrates the complexities and challenges of coping with an ever-changing crisis.

At the same time, much of Kerala’s healthcare workforce was unable to function at maximum efficiency due to pandemic fatigue, with many frontline workers contracting the virus themselves. While strict surveillance measures were in force during the first wave of the pandemic, police, and other personnel could no longer enforce social distancing rules as earlier.

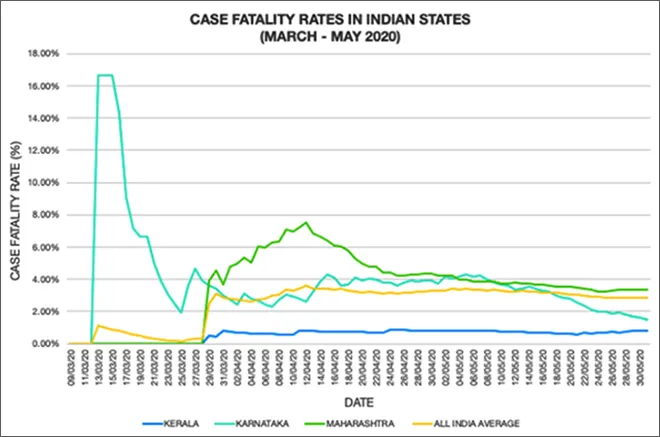

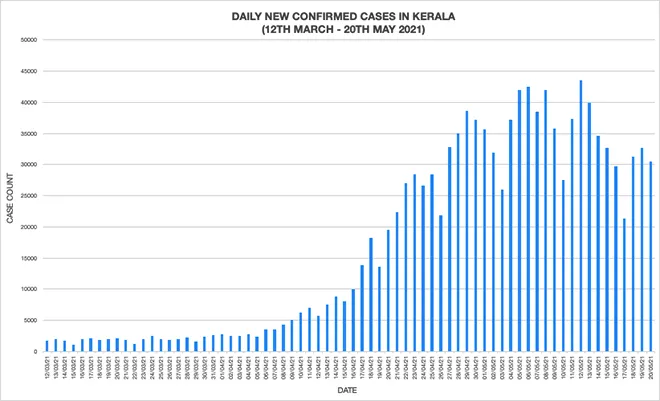

In March and April 2021, electoral politics was the biggest driving force behind the surge in cases, with large campaign rallies throughout. Figure 3.1 below denotes the impact of the Assembly Elections on cases. It covers the timeframe from when the election campaign kicked off, to the day that Vijayan took his oath to become chief minister for the second time. Contesting candidates interacted directly with voters and social distancing norms were flouted. Only after over 30,000 daily new cases were reported towards the end of April and after large crowds gathered to celebrate the election results on May 2nd, did Kerala declare a month-long state-wide lockdown.

Figure 3.1; Source: api.covid19india.org

Figure 3.1; Source: api.covid19india.org

The current predicament

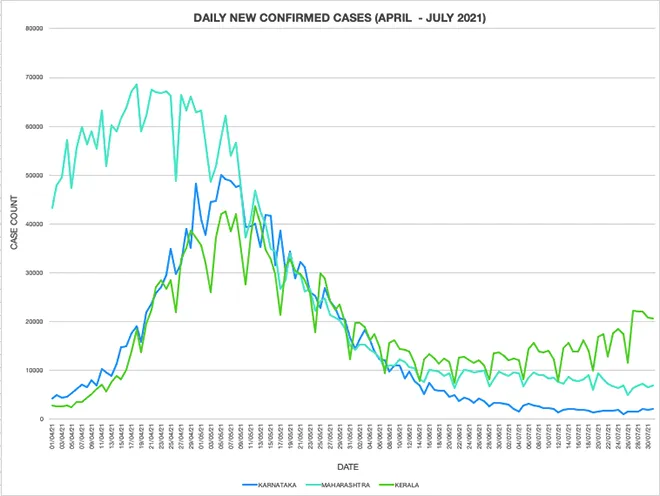

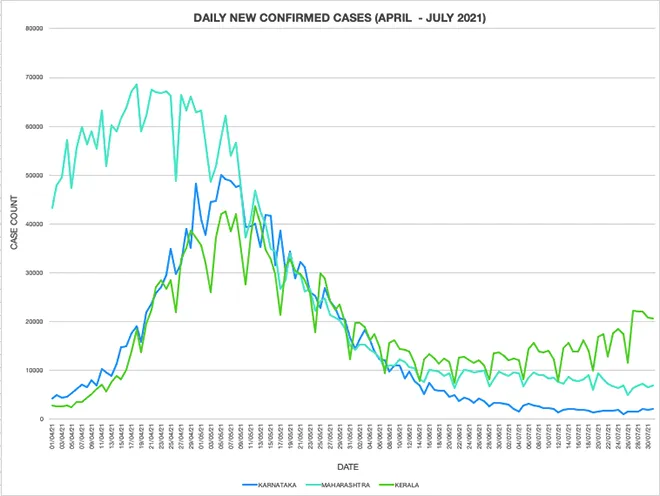

Kerala is experiencing a unique trend, where numbers are rising and diminishing at a much lower rate compared to other badly affected states. During the first wave, its strategy was to delay the peak of the curve to prevent its health infrastructure from becoming overwhelmed. Some officials say that the state might be continuing the strategy that it followed in the first wave in order to prevent its healthcare system from being overhauled by an unmanageable caseload.

Figure 3.2 below compares the daily new case count in Kerala with that of Karnataka and Maharashtra which were also badly affected over the last few months:

Figure 3.2; Source: api.covid19india.org

Figure 3.2; Source: api.covid19india.org

The aforementioned serosurvey also shows that Kerala has been reporting one in sixs positive cases amongst its population. This is twice as many cases as Maharashtra which is underreporting by a factor of 12, followed by Karnataka by a factor of 18. Due to the lack of transparency and poor detection systems elsewhere in the country, India has collectively been able to report as few as 1 in 33 cases. This suggests that Kerala is not performing as badly in comparison with the other states as the numbers seem to indicate. Rather Kerala’s system of reporting numbers presents a more accurate picture of what it has been experiencing.

However, there have been criticisms that the Kerala government has not been forthcoming with accurate data on COVID-19 deaths, which is in turn influencing its extremely low case fatality rate. This is puzzling given the high capacity of its system. In contrast to the number of deaths reported at the district level, the state government’s official numbers do not include those who have succumbed to illness due to comorbidities, which violates ICMR’s guidelines for reporting COVID-19-related deaths. For instance, as of 11 November 2020, fewer than 15 percent of deaths recorded by the District Collector in Pathanamthitta were recognised by the State Government.

Some experts contend that this is a deliberate effort to protect the image of Kerala and its widely lauded Development Model. More transparency is only starting to emerge now because of a Supreme Court mandate to release the names of the deceased to ensure that bereaved families are awarded compensation under the provisions of the Disaster Management Act.

Conclusion

The Kerala experience in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic illustrates the complexities and challenges of coping with an ever-changing crisis. As seen through the state’s stellar response to the pandemic, consistent efforts to benefit all sections of society yield good outcomes in the long run. The Kerala Development Model has, therefore, proven the test of time up to this point. Amidst rising numbers, the possibility of a third wave looming, and the recent onset of the mosquito borne Zika virus in the state, Kerala’s robust healthcare system will be put to its greatest test yet.

Rishika Gowda is a research intern, ORF.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV