A cursory glance depicts beyond doubt the heavy handedness of imperial powers, shades of which are evident even today. The stark similarities in terms of past suffering and violations of human rights of the people in different regions, resonates loudly. As a result, it becomes incumbent to analyse these things in contemporary global context and probe a few searching questions.

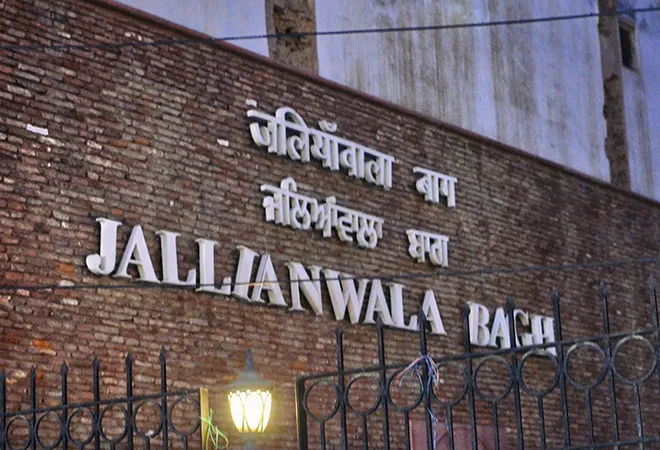

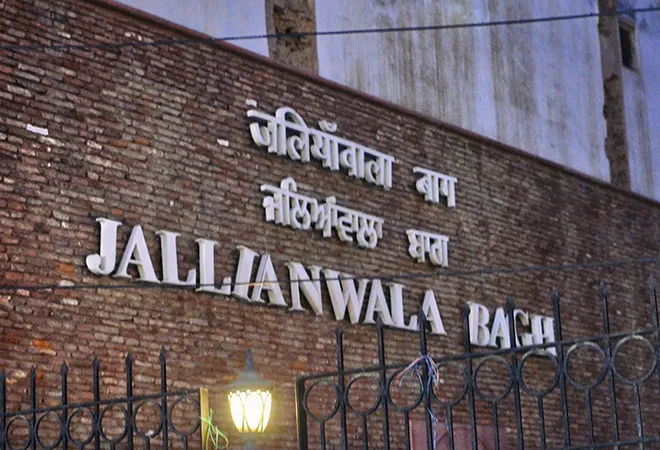

The brutal torture of the Kenyan people during the Mau Mau emergency by means of the British has much in common with what happened in Amritsar on that fateful day of Baisakhi in April 1919. The cross-Atlantic slave trade and repression of the people of the Caribbean and Brazil by the Portuguese stands in line with the cruelty and oppression suffered by the indigenous peoples of Mexico by the agency of the Spanish conquests. Finally, the exploitation and abuse of women from Korea at the hands of Japan’s imperial military as “comfort women” highlights the extent of injustice and discrimination, which needs to be atoned.

Before delving into the ways in which certain states have recompensed for past excesses and the possibilities for others who have not done so, it is crucial to observe the forces, which completely ignore or neglect to do so.

However, before delving into the ways in which certain states have recompensed for past excesses and the possibilities for others who have not done so, it is crucial to observe the forces, which completely ignore or neglect to do so. For instance, there is a logic, which informs UK junior foreign minister Mark Field’s opinion that, “we debase the currency of apologies if we make them for many events.” There is also an argument that making full apologies and paying reparations would set a precedent under which the Portuguese may be expected to compensate nations they exploited in colonial times. Simply so, it could stir a hornet’s nest of misconducts of former colonial empires.

Following from the above, Nicholas Lloyd, a British historian, in his book, The Amritsar Massacre: The Untold Story of One Fateful Day, suggests that it was Gandhi, who was responsible for the killings of protesters in Amritsar. According to him, Gandhi’s Satyagraha and the consequent people’s refusal to obey The Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act of 1919, popularly known as the Rowlatt Act, amounted to becoming a terrorist. This logic perhaps, reeks of the jurisprudence of nineteenth century British legal theorist, John Austin, who studied law in a value-free way. Austin’s imperative theory suggested that law is the command of the political sovereign, backed by sanction. Any act to the contrary, howsoever just, fair and reasonable would invite the application of law, more correctly the officially recognised and stated law. Therefore, this jurisprudential inexactitude being in consistency with the moral bankruptcy of colonialism.

Austin’s imperative theory suggested that law is the command of the political sovereign, backed by sanction. Any act to the contrary, howsoever just, fair and reasonable would invite the application of law, more correctly the officially recognised and stated law.

British PM Theresa May’s comment of deep regret in the House of Commons, when a debate on formal apology was going on, was much in line with her predecessor David Cameron’s, who when in office described the Jallianwala massacre to be a deeply shameful event. Therefore, these comments falling short of the formal apology desired by the impacted parties. The UK foreign office stated that such apologies would have financial implications. This suggesting that the UK wants to stay afar from getting itself fully recognised for the wrongful acts it did in India and sparing itself from any future liabilities, which may otherwise follow, once such an apology is made. In addition, it is worthy to mention that UK opposition leader Jeremy Corbyn criticised his government and demanded that, “those who lost their lives in the massacre deserve a full, clear and unequivocal apology for what took place.” Thus, wanting to move from a sense of regret or shame to a formal apology.

In contrast to this, the Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in 2015 had apologised formally for the excesses committed by its military during World War II. Financial reparations from the Japanese budget have been made towards restoration of the women who were dehumanised. Similarly, in the case of denying the passengers of Hindu, Sikh and Muslim origin in 1914, on board the Komagata Maru, entry onto the Canadian shores, Canadian PM Justin Trudeau, in 2016 stated, “First and foremost, to the victims of the incident, no words can erase the pain and suffering they experienced. Regrettably, the passage of time means that none are alive to hear our apology today, still, we offer it, fully and sincerely, for our indifference to your plight, for our failure to recognise all that you had to offer. For the laws that discriminated against you so senselessly, and for not apologising sooner. For all these things, we are truly sorry.”

In the case of Mau Mau emergency, the British administration of colonial Kenya was found wanting. The then foreign secretary, William Hague, in June 2013 tendered an apology and the UK government paid compensation to the victims or next of kin amounting to 19.9 million pounds. In this context he said, “We understand the pain and the grief felt by those who were involved in the events of emergency in Kenya. The British government recognises that Kenyans were subjected to torture and other forms of ill-treatment at the hands of the colonial administration.” However, in this case it is crucial to note that five of the torture victims brought a legal case in the UK High Court, which resulted in the above shift of the UK from ignorance to acknowledgements of its past wrongs.

It is crucial to note that five of the torture victims brought a legal case in the UK High Court, which resulted in the shift of the UK from ignorance to acknowledgements of its past wrongs.

In international law, reparation for injury done by the wrongful acts of states can take three broad forms, as mentioned in International Law Commission (ILC) Articles on State Responsibility. The first form is restitution, that is, to re-establish the situation, which existed before the wrongful act, was committed. Second, if restitution is not possible then there is compensation. It covers any financially assessable damage including loss of profits insofar as it is established. Lastly, if both of the above are not able to atone for the wrong done then there is satisfaction. It may consist of an acknowledgement of the breach, an expression of regret, a formal apology or another appropriate modality. While these are three separate forms of reparation, a combination of the above is also employed.

Early this month, the Belgian Prime Minister gave a formal apology in a plenary session of their Parliament for the kidnapping, segregation, deportation and forced adoption of thousands of children born to mixed-race couples during its colonial rule of Burundi, Congo and Rwanda. Gestures like these comfort the victims and provides a sense of closure to their horrific past. It helps in building a regime of law and politics, which keeps the individual at the forefront. It strengthens social justice. It gives human rights a context and subtext, which no other recognition can lend. Thus, allowing bitter power dynamics of past colonies and empires to transform into a relationship of equal rights.

What may have stopped the UK government from making a clear and full apology is unknown. It may be in line with rising nationalism and needs of getting through with Brexit. It may be the financial cost, which such an apology entails. It maybe the fear of joining and strengthening the precedent of atonement as established by the Mau Mau case. It may be a decent composition of the above and some other constraints. However, if Mark Field, the junior minister in Theresa May’s government, feels that the currency of apology will be debased, if used frequently, the UK may certainly go bankrupt one day. It is only time that former colonised countries take recourse to courts and other legal mechanisms. Informal attempts are only generating that which has been said or that which should not have been said. The attempt made by British parliamentarians to make their society more conscious of their past has fallen through. The fact that it was made gives hope of a better future.

The author is a Research Intern at ORF Delhi.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV