Is it the world’s financial future? Or is it a scam? Or worse, is it a shiny new tool to facilitate money laundering and fraud? The government has listed a new law to be introduced in the winter session of Parliament to regulate cryptocurrencies. However, the exact proposals in the Bill are still not in the public domain. But the matter has been top-of-mind for policymakers, with PM Modi himself alluding to the risks/opportunities of cryptos recently.

It’s a good time to explore the possibilities around regulating cryptos in India, starting from first principles.

The big macro questions on the impact of cryptocurrency, on fiscal and monetary policies, remain unanswered. But the micro case is getting stronger. What was a geek fad not so long ago found institutional backing during the course of 2021 – almost every large financial institution globally, including Wall Street giants like Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan, have set up (or started the process of setting up) crypto offerings for their customers. The US Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) recently approved two Crypto ETFs for listing in the US.

Crypto – Currency or Asset class?

Alternative Currency? Fundamental source of discomfort

One of the core structural attributes of the nation state is the sole monopoly to issue fiat currency. Along with a legal monopoly on violence, it allows the modern nation state to exercise control over fundamental levers of economic social contracts—trade, banking, taxes, government intervention to correct imbalances etc.

Domestic central banks lose the ability to influence interest rates and manage liquidity in the economy if the dominant currency is issued by a foreign government.

A private cryptocurrency competing with fiat currencies upends this arrangement. It is not uncommon for countries to depend on a non-domestic fiat currency—there are dozens of African and Latin American countries where the US Dollar has been (and is still) the default primary currency in use. In yet more cases, while there is a domestic currency still in circulation, USD (or other “hard currencies”) are preferred modes of exchange. But all these cases are in countries with serious, even complete, breakdown of confidence in the state itself. Zimbabwe, Venezuela—in recent times—represent cases where there are widespread questions on the ability of the state to govern, leading to a breakdown of trust in tools of the state (including its fiat currency). In some ways, it is similar to private residents raising private militias for security, as a result of a breakdown of confidence in the state’s monopoly over violence.

But the “Dollarisation” of domestic economies has serious impact on monetary and fiscal policy settings. Domestic central banks lose the ability to influence interest rates and manage liquidity in the economy if the dominant currency is issued by a foreign government. Further, the domestic central banks lose their seigniorage revenues – difference between the 0% interest on each currency note issued and the same deployed by the central bank into interest-bearing domestic financial instruments (like bank reserves, government securities etc). In effect, dollarised countries end up importing the monetary policy of the US Fed and losing seigniorage revenues to the US Fed.

Private cryptos as “currency” is rightly feared to have similar potential impact. Just as “Dollarisation” effectively results in the economy importing US monetary and fiscal policy, “Crypto”-isation will mean importing the monetary policy engendered by a privately owned currency. The larger the developed ubiquity of cryptos as a medium of exchange, the less influence will domestic monetary policy tend to have on monetary aggregates—interest rates, money supply, capital flows. A monetary system with heavy influence of privately-owned currency will also have large, unpredictable tail-risks on macro stability, which no central bank would be able to predict, model and counter-act. There is simply no data currently to model the tail risks of a privately-owned currency system. The risks are magnified for an economy like India, which runs a net trade deficit and a non-convertible currency – unpredictable capital flows engendered by privately-owned cryptos can impair systemic stability faster than policymakers’ ability to take corrective actions. Last but not the least, cryptos, given their anonymous signatures, can be a source of illicit transactions and finance, which would strain fraud risk and compliance bandwidth of most countries.

A monetary system with heavy influence of privately-owned currency will also have large, unpredictable tail-risks on macro stability, which no central bank would be able to predict, model and counter-act.

Crypto as an Asset Class – A more plausible use-case

Every asset class in existence today – Currency, Bonds, Equities, Commodities, Gold – has one fundamental attribute, i.e., it is perceived to be a “store of value”. To be a store of value, the instrument can either have embedded stream of cash flows (Bonds, Equities), sovereign guarantees (fiat currencies like INR, USD) or real-world uses (Commodities). By the same definition, can cryptos like Bitcoin qualify as an asset class? As Michael Novogratz (Co-founder of Galaxy Digital Holdings) says, it is, because “the world has voted that they believe” it is. That, truly, is the touchstone for anything as a store of value – as long as a large enough pool of people believe that a particular instrument is a store of value for them, that instrument self-qualifies as a store of value, also known as an asset class.

Less controversially, crypto assets have significant potential use cases – Decentralised Finance (DeFi), Secure data storage, Non-Fungible Tokens (NFT) and Cross-border funds transfers. The power of networks spawned by these use cases should be immensely valuable. Just as digital companies derive a large part of their value from the power of the data they access and network externalities they spawn, cryptos that power useful applications should follow the same path.

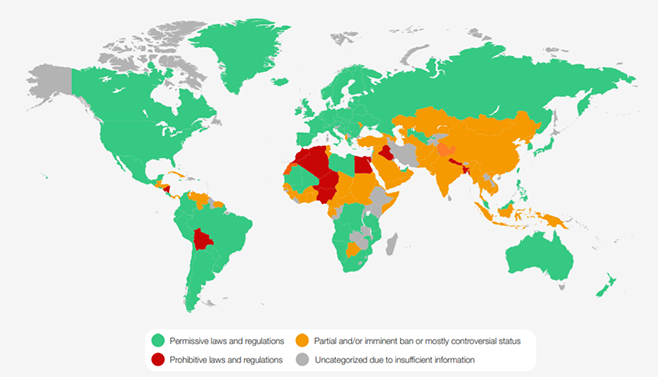

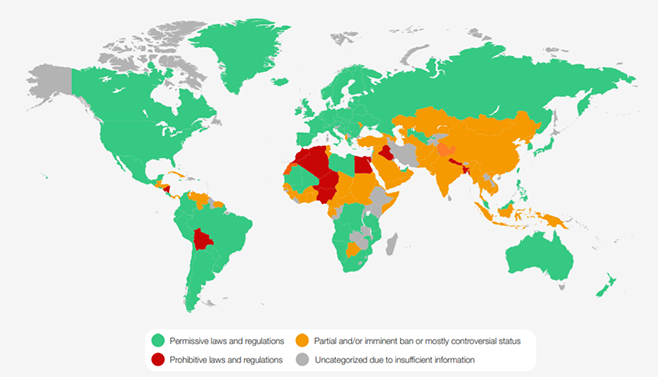

Global Regulatory landscape today

Source: World Economic Forum

Source: World Economic Forum

Contrary to the general media commentary, large swathes of the world have taken to cryptos with more sanguine optimism than outright hostility. The level of permissiveness can range from enthusiastic embrace (like El Salvador, which has given Bitcoin status of official currency) to weary and grudging acceptance (like the US, where a skeptical SEC has recently given a go-ahead to 2 crypto ETFs). Caution and hostility seem to be more in Asia and parts of Africa – unsurprising given that these are the very economies that have the highest macro stability fears. The advanced economies, by and large, have veered around “sandbox” approaches, where select pieces of the crypto jigsaw are actively encouraged to seek out and examine outcomes.

Regulatory Imperatives for India

Some of the questions are self-answered for India, but some need careful analysis and deliberation.

- Cryptos as currency is a clear no for India, as it will be for vast majority of countries around the world. A large complex economy with multiple and growing linkages cannot afford macro instability. We are certainly not at a stage of evolution where the state can share fundamental tenets of state monopoly like currency issuance.

- Fraud prevention and control. Contrary to popular belief, data shows that a very small proportion of crypto transactions globally (0.34%, as per the Crypto Crime Report by Chainanalysis) are to facilitate illicit transactions. This number, if true, is lower than the share of illicit transactions via traditional financing mechanisms. Even if the number is higher, and potential (for illicit transactions) even more so, the best solution is to regulate cryptos via Gated Trading Rooms (GTR) – large, nationally-recognised and regulated intermediaries. A “laying off” mechanism of oversight – finessed over several centuries in Finance – would work seamlessly for another asset class being included in the realm of finance. These GTRs – think of a regulated Indian Coinbase – will attract capital and create vested interest in ensuring high levels of compliance. Global coordination between such intermediaries and countries is a next step – something that has already been templatised over the last 2-3 decades. Automatic Exchange of Information, globally harmonised KYC (Know Your Customer) are all mechanisms that can be the first test-beds for crypto regulation as well.

- Capital account stability. Given the relatively low base of crypto holdings with Indians today, bulk of the settlements for buying and selling cryptos happen in fiat currencies like USD. Ergo, if Indians buy a large volume of cryptos mined outside India, it would result in large foreign exchange outflows. Conversely, if foreigners bought a large amount of cryptos mined in India, it would cause large foreign exchange inflows. The best approach to mitigate capital account risks would be, again, via GTR. Just as India restricts capital account inflows via specific restrictions on holdings – there is a cap, for example, on the amount of Indian bonds that can be held by foreigners – similar caps on GTR exposure to foreign cryptos (and foreign purchases of Indian cryptos) can be imposed and monitored.

- Investor protection. Today, sans any regulation, cryptos are being marketed as consumer products, promoted by cricket and Bollywood stars, sans normal investor protection frameworks. Bringing cryptos (and GTRs) as a separate asset class under the regulatory supervision of SEBI will bring in custody protocols, certification, risk disclosures, suitability – all building-blocks to a well-discovered investor protection architecture.

If foreigners bought a large amount of cryptos mined in India, it would cause large foreign exchange inflows.

Banning private cryptos – Digital Haji Mastans instead of Web 3.0

The easiest policy response to an unknown, evolving, somewhat uncomfortable instrument is to ban it. As a response to foreign exchange shortage, India adopted that stance for imports (especially of Gold and high-priced consumer goods) in the 1960/70s. The outcome though was merely to shift trade into illicit channels – flow of both goods and consideration for the same got transferred to those illicit channels. Foreign exchange still went out of the country, and those with means still bought Gold and expensive electronics. Government lost out on tax revenues, legal businessmen lost out on a legitimate business opportunity. Haji Mastan, later via movies, came to symbolise that shift. India, being one of the world’s hottest innovation hotspots, has a great opportunity to lead the world on development of a crypto eco-system. Having ultra-restrictive regulatory architecture, like bans, is merely going to spawn digital Haji Mastans and not achieve the desired regulatory outcomes.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are personal.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV