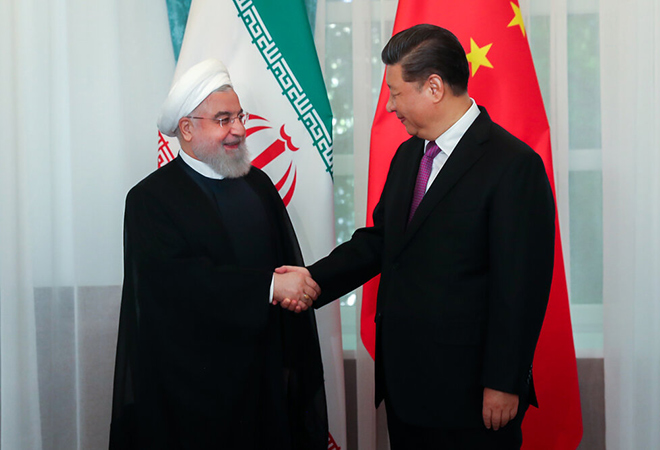

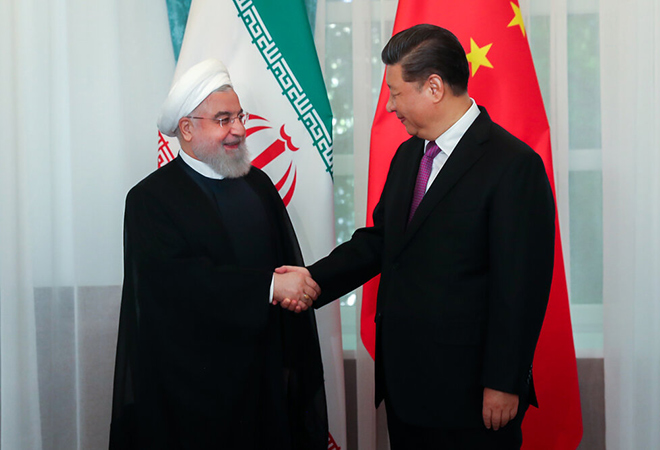

As China faces increasing heat from the international community over its aggressive political and military postures, ranging from Ladakh in the high Himalayas with India, the South China Sea region and beyond, Beijing is also looking to solidify its relations with Iran in the Middle East as the Shiite power faces a “maximum pressure” policy from the US in the form of crippling sanctions and military options. The foundation of this impending “deal” between Beijing and Tehran was laid during President Xi Jinping’s visit to Iran in 2016.

According to reports, Beijing and Tehran are nearing the conclusion of an extensive trade and military partnership. For Iran, such a deal could throw the embattled country a much-needed economic lifeline. Iran is already part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and in September 2019 China announced its intent to infuse $400 billion worth of investments in Iran’s oil and gas, infrastructure and transportation sectors. These massive numbers are a direct challenge to both Western, and more specifically, American economic might on a regional and global stage, but also creating new geo-political flash points as Beijing expands its reach around the world, which now includes a base in Djibouti, operations of the Gwadar port in Pakistan, ever increasing naval port calls across the world and so on.

The Iran – China deal is turning out to be a well-timed chimera, with most details available this past week coming from a report which claims to have got access to a copy of the 18-page proposed agreement. Some reports initially also suggested that as part of the deal, the geo-strategically important Kish Island in the Persian Gulf, located at the mouth of the Strait of Hormuz may be ‘sold’ to China. However, these claims were refuted by Iranian officials.

The US – China tussle arriving in Iran would be a new challenge within a challenge for New Delhi, which has over the past few years been balancing its relations with the US and Iran. Despite popular consensus that President Donald Trump’s policy of “maximum pressure” against Tehran has pushed India in a corner over its relations with the same, it was in fact the administration of former president Barack Obama that really turned the keys on New Delhi with regard to Iran, pushing the then government of Manmohan Singh to not only dry the oil trade taps, but also use India’s position with Iran to nudge the regime towards an agreement with the West on back of economic windfalls the Iranian economy would enjoy if the deal succeeds. India kowtowed the US line, helping create the narrative to Tehran of an agreement with the P5+1, curbing oil trade, initially disallowing Iranian banks’ to open branches in Mumbai and so on.

The US – China tussle arriving in Iran would be a new challenge within a challenge for New Delhi, which has over the past few years been balancing its relations with the US and Iran

Trump withdrew the US from the Iran nuclear deal in 2018 after it was signed in 2015 through long and difficult negotiations. The eventual withdrawal emboldened the significant conservative lobby within Iran, which had stood against any deal to begin with being negotiated by President Hassan Rouhani and Foreign Minister Javad Zarif. The loss of the deal and return of sanctions was as poor a strategy geo-politically by the Trump administration as it was from the view of building bridges within Iran, propping up the moderates already in power, and perhaps most importantly, courting via economic and market incentives the country’s massive youth population. Over 60 percent of Iran’s population of 80 million people is under the age of 30. All of this culminated in Iran gaining a higher moral ground to the US, accurately arguing that while it signed the JCPOA, it was the US that unilaterally withdrew leading to a crisis all over again.

For India, an extensive economic and security pact between Iran and China raises some critical concerns. The Chabahar port project, often scene as India’s strategic magnum opus in Iran, is also envisaged as a bridge between India, Iran, Afghanistan and Central Asia. The port itself is often seen as a counter-balance to Gwadar in Pakistan, which was built and run by China as part of its China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) design. The distance between the two ports is only 172 km, and both Gwadar and Chabahar are in fact often postured as “sister ports” by Tehran and Islamabad, despite India’s narratives on the same. Previously, Iran has not shied away by leveraging both China and Pakistan as potential investors for the Chabahar Special Economic Zone, challenging Indian public narratives of Chabahar seemingly being an India-exclusive project. This tactic has been employed over the Farzad-B natural gas project as well, which was discovered by ONGC Videsh in 2008 and since then has been caught up in financial difficulties, bureaucratic trappings and of course, international sanctions. In the middle, unannounced arrival of Iranian delegations in New Delhi and reports alluding to ‘other’ countries (referring to China) benefiting from India not coming through on its investments despite sanctions were used as pressure tactics to prod India. ‘Iran won’t wait for India on Farzad-B gas project’, read an August 2019 Tehran Times headline. More recently, reports suggest that Iran has also decided to build the rail line connecting Chabahar with Zahedan on the Afghan border alone, citing delays in funding from India. These gaps were not always the case, with institutions such as the IranoHind friendship shipping company created 46 years ago, being allowed to collapse by both countries in 2012 due to sanctions, posing as a reminder of past successes. The success of JCPOA was seen as an opportunity to revive such joint commercial operations.

The development of Chabahar has often come under duress due to financial, political and diplomatic largess by both India and Iran, and also due to US pressure along with sanctions blocking most legitimate financial highways to and from Iran. In December 2019, reports suggested the US gave ‘written’ assurances that it would give waivers to India to facilitate equipment purchase for the port development. However, most suppliers being European and, now ironically, Chinese, feared their names featuring in US blacklists, delaying the project further. For Chabahar, and India’s balance act with the US, the game changer was Afghanistan, and its access to the port as well. In February 2019, the first load of Afghan goods traded through Chabahar, highlighting the economic use of the project for greater stability of Afghanistan, a country the US is currently negotiating its way out of a 19-year-old war with the Taliban. With Chabahar being one of the few international trade routes operational for the Afghan economy, sanctioning India from building upon and operating it would have been too myopic even for the Trump administration.

The development of Chabahar has often come under duress due to financial, political and diplomatic largess by both India and Iran, and also due to US pressure along with sanctions blocking most legitimate financial highways to and from Iran

Despite a growing consensus, with a good degree of truth to it, that Trump’s withdrawal from the JCPOA and attempts try and corner Iran is pushing Tehran to build alliances with China, the reality however remains that Xi Jinping’s visit to Tehran in 2016 was 10 months prior to the US elections, and swearing in of Trump as president. This plan was already on the move before. Discussions between China and Iran have been sluggish, with Beijing cognizant of the fact that an overt military alliance with Iran will arguably off-balance its relations with the Arab world and Israel as well (Iran however did participate in joint military exercise with China and Russia in the Gulf of Oman). Even through the argument of cheap oil, other large suppliers such as Saudi Arabia recognize China’s place in the global disorder playing out. China’s oil imports from Saudi Arabia in June 2020 surged by 94% on the year, and by 71 percent on the month in May 2020 as it imported its highest-ever volume of crude oil due to low oil prices and uncertainty over economic impact of Covid-19. The top two oil suppliers for China in May and June 2020 have been Saudi Arabia and Russia, and not Iran. Both Russia and China have worked in concert to try and protect Iran against fresh US sanctions; in return, Tehran, along with the Arab world, has maintained silence on China’s ill treatment of more than a million Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang detention centers.

Like previously, a lot of signaling takes place when China discusses strategic cooperation with another country. The potential of billions of dollars in investments is almost always on the table, how and when, and if, that actually materializes is a different matter. Even Iran would be wary of an overt presence of China in its economy, which is tightly controlled by elites close to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei along with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), and its full control is critical for its regional and foreign policy objectives. Zarif’s surprise visit to the G-7 summit in Biarritz, France, in August 2019 showed that despite the China dynamic being strong, Tehran was continuing to aggressively pursue its European outreach, playing China as a stick in front of the European powers to expedite the process of delivering the carrots, putting the onus on Berlin, Paris and London to deal with Washington D.C.

For India, going forward after the almost-war like situation with China in Ladakh, an institutionalized slide towards the US today may potentially come at the price of hedging itself over Iran as per Trump administration’s narratives. However, the modalities of an Iran – China strategic partnership would be of vital interest to India not only as part of its relations with Tehran, but more importantly as per China’s access to the Indian Ocean region, connecting via Gwadar, Djibouti and possible permanent military accesses arrangement with Iran.

For India, going forward after the almost-war like situation with China in Ladakh, an institutionalized slide towards the US today may potentially come at the price of hedging itself over Iran as per Trump administration’s narratives

All this, makes the upcoming US elections even more important. A Trump victory could see Iran remaining in the limelight while a Joe Biden victory, who was Vice President when JCPOA was signed, may witness some relief. While signaling a “strategic” document and operationalizing it are two different behemoths, as New Delhi knows so well, the decision of engagement here is more important in the calculus of Beijing’s strategies than those of Tehran. All said and done, New Delhi will be keeping a hawk's-eye on the same.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV